Spring Budget 2023

The spring budget is an opportunity to invest in our public servants and public sector, after a decade of austerity that has left them at breaking point.

The budget comes at a time when:

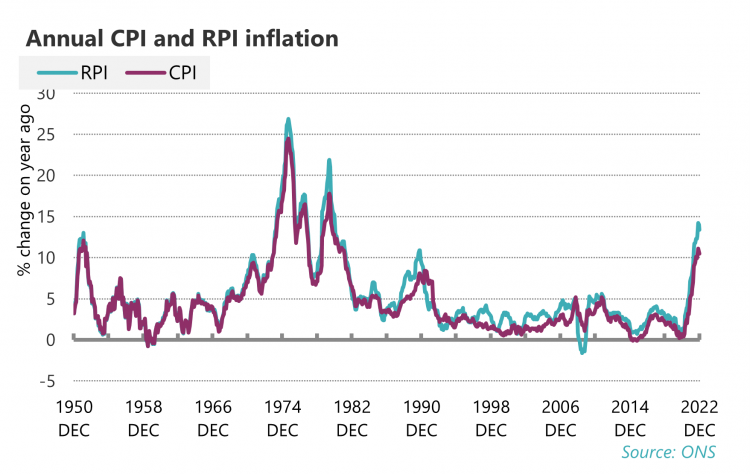

- real pay is falling steeply, by -3.8 per cent on CPI and -6.3 per cent on RPI, as inflation, driven by global factors, has reached a 40-year high.

- the threat of a two-year recession, and a rise in unemployment between ½ million and 1 million, according to forecasts from the Bank of England and Office for Budget Responsibility.

- there is a recruitment and retention crisis in public services, with vacancy rates of over 10 per cent in health and social care, and one third of public sector workers actively seeking to leave their profession citing pay cuts as the determining factor.[1]

Workers are taking industrial action across the public and private sectors, in response to 12 years of falling pay and an environment that has repeatedly asked workers to pay the price while dividends and executive pay have soared.

Strong and resilient public services are the backbone of a strong and robust economy. But in the Autumn Statement 2022, the Chancellor failed to mitigate the impact of soaring inflation on departmental budgets, first set out in the 2021 comprehensive spending review, forcing public services to provide the same level of service on far less than originally intended. Calculations by the new economics foundation suggest that, at the Autumn Statement in November 2022, the Chancellor introduced cuts provisionally estimated at £80bn, by the end of the forecast period 2027-28.[2]

This amounts to an impossible task for our public services and the workforce. The scale of the challenges facing our public services are immense, from record backlogs in health and justice, soaring levels of unmet care needs to crumbling school buildings and acute staffing shortages. The latter challenge has been made worse by the government’s intransigent approach to public sector pay.

The decision to hold down public sector pay for 12 years has led to the recruitment and retention crisis in public services and a race to the bottom on public sector wages. Key workers are voting with their feet, leaving in droves, in search of better paid jobs. Vacancy rates in health and social care have reached record highs at 10.5 per cent[3] and 10.7 per cent respectively[4]. In education, retention rates have reached a historic low – just two-thirds of early-career teachers (67 per cent) remain in the profession after five years.[5]

The focus of the Chancellor’s Spring Budget should be investing in public services and the workforce that deliver them. Through plans laid out in the Budget, the Chancellor should empower Ministers to resolve the public sector pay disputes of 2022-2023, providing sufficient funding to deliver fair pay rises, adjust spending plans to account for the impact of inflation on departmental budgets, and deliver fully-funded pay rises that enable us to recruit and retain the skilled staff we desperately need.

Yet, once more the Treasury seem determined to pick a fight with workers rather than address the disaster of the economy and public services, of broken Britain. Rather than pay key workers what they are owed, the government are threatening to sack them with the Minimum Service Bill. The wealthy are yet again exempt, with city bonuses at an all-time high and new tax breaks for banks. There is no ownership of the severity of the crises that have led to this point. Repeating the mistakes of the last decade, when public spending and public sector pay was held down, will place further pressure on the economy. While inflation continues to put immense pressure on households, the threat of a prolonged recession is looming large. Just as workers need higher pay and better social protection to support a standard of life that has fallen behind and has pushed millions into poverty, higher wages are needed to protect the economy.

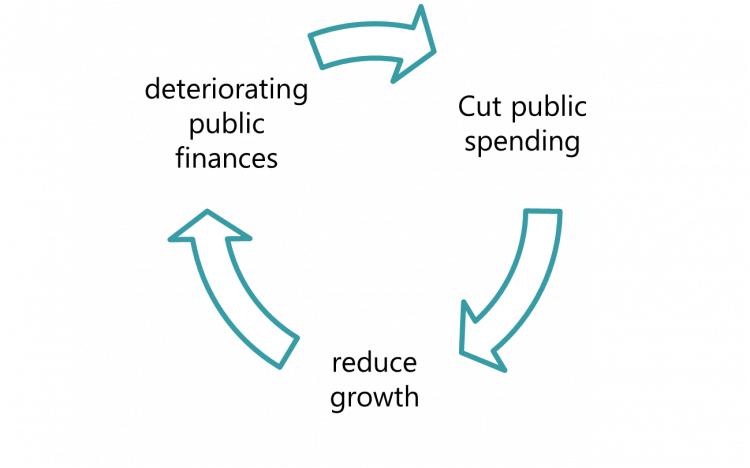

Government policies have engineered a doom loop of low pay, weak spending, low growth, and consequent pressures on the public finances. But rather than trying to reverse this cycle, the government is arguing once more that the state of the public finances is a reason to restrict economic growth, flying in the face of evidence to the contrary.

Public spending supports employment, drives economic growth and ensures we have a healthy and skilled workforce.[6] Conversely, failure to invest and create a more equitable tax system, drives the opposite results, particularly in the context of high inflation and an economic recession.

Without a change in direction, the economy will continue to go backwards not forwards. At the Budget, the Chancellor must set out a genuinely new approach that builds for fair growth and decent jobs – recognising that rewarding the workers who keep the country running is the best way to ensure that growth benefits everyone.

[1] TUC (2022) Around 1 in 3 key workers in the public sector have taken steps to leave their profession or are actively considering it | TUC

[2] NEF (2023) ‘Austerity by stealth’ *publication pending; this figures includes an adjustment for what is regarded as an “implausibly low inflation forecast” on the part of the Office for Budget Responsibility. The estimate is then relative to the scenario where a) the government delivered against their original commitment to increase budgets by 3.8% a year in real terms for the duration of the current spending review period, and b) thereafter spending tracks nominal GDP (in line with the OBR’s baseline assumption).

[3] NHS Digital (2022) NHS Vacancy Statistics (and previous NHS Vacancies Survey) - NHS Digital

[4] Skills for Care (2022) https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/Adult-Social-Care-Workforce-Data/Workforce-intelligence/publications/national-information/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-in-England.aspx

[5] House of Commons library (2022) Teacher recruitment and retention in England (parliament.uk)

In the Spring Budget, the Chancellor should take action to:

Boost pay across the economy

- Fund decent pay rises so that all public service workers get a real-terms pay rise that protects them from the soaring cost of living and begins to restore earnings lost over the 12 years.

- Get the UK on a path to a £15 minimum wage as soon as possible.

- Follow the example of New Zealand and Australia by introducing fair pay agreements to allow unions and employers to negotiate minimum pay and conditions across sectors.

- Ensure all outsourced workers are paid at least the real living wage and receive pay parity with directly-employed staff doing the same job.

- Strengthen the gender pay gap reporting requirements, and introduce ethnicity, LGBT+ and disability pay gap reporting, requiring employers to publish action plans on what they are doing to close the pay gaps they have reported.

Deliver a plan for strong public services and fair taxation

- A new funding settlement for public services, with adjusted spending plans that mitigate the impact of high inflation on departmental budgets and provide for fully-funded pay rises that keep pace with the cost-of-living.

- Ensure those with the broadest shoulders pay their fair share in tax. Equalise capital gains tax rates with income tax to start ensuring the fairer taxation of wealth and tax windfall gains experienced by oil and gas giants at a higher rate, removing loopholes that allow businesses to avoid paying their fair share.

- Deliver a new economic vision built on strong and robust public services, investing in key areas of our economic infrastructure that have historically been overlooked and underfunded including childcare, social care and local government.

Protect workers from hardship

- Cancel the imminent hike in energy bills. The Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) must not be raised beyond the current £2,500 - government should either reduce the EPG to £2,000 or accelerate the introduction of a social tariff. Government should increase domestic energy efficiency spend by £6 billion over the next two years, funded by planned EPG spending coming in significantly under budget due to falling gas prices. 1

- Implement a short-time work scheme to protect jobs in the event of economic downturn.

- Set a path to significant and permanent improvements in the levels of social security.

- Commit to maintaining the State Pension triple lock for the rest of this parliament to help reverse increases in pensioner poverty rates and to reduce income inequalities among households in retirement, which has reached record levels. 2

Ensure decent jobs and growth for everyone

- Ensure that businesses prioritise sustainable growth and jobs, reforming corporate governance to promote long-term sustainable investment rather than a short-term focus on shareholder returns.

- Invest in a just transition to the secure green energy future we need, slashing dependence on volatile imported gas, and introducing public ownership to the energy sector.

- Get productivity rising by rebooting our skills system through a new national lifelong learning and skills strategy.

- Drop plans to threaten EU-derived employment rights through the Retained EU Law bill.

- Scrap the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Bill that would undermine workers’ right to strike.

- Introduce industrial and trade policies that promote good jobs and workers’ rights globally and ensures that businesses compete on a level playing field.

- Institute the Green Jobs Taskforce with a long-term remit and regulatory capacity to co-ordinate planning for decarbonising our economy, between government, industry, unions, and skills sector, building on the work of the current Green Jobs Delivery Group.

The following sections outline the impact of government policies over the past decade, and the current situation facing workers. The final section outlines the new approach workers need in more detail.

Strong and resilient public services are vital for a strong and robust economy. Public spending supports employment, drives economic growth and ensures we have a healthy and skilled workforce.

Since 2010, our public services have been deliberately under-resourced and under-staffed by successive Conservative governments. International spending comparisons show that UK spending on health is 18 per cent less than the European average and would need to rise by £40bn a year to match per capita health spending.9

Austerity approaches to public spending harm our economy, stalling productivity and growth, as we have witnessed throughout the last 12 years – see sections 4 and 6. They also harm our overall health and wellbeing. The crisis in social care and its consequences are the clearest example of this.

The levels of unmet care needs in the UK were unacceptably high before the pandemic, and were exacerbated during the crisis. Acute staffing challenges in social care meant that 1.5 million hours of commissioned home care could not be provided between August and October 2021 because of a lack of staff.10

The number of people awaiting assessment for care in England increased in 2021/22 – as of September 2021 an estimated 70,000 people were awaiting assessment, which quadrupled to 294,000 people as of April 2022.11

The lack of care, or delays in initial assessments for appropriate care, are putting people at significant risk. Without the care or support people need, health conditions are likely to deteriorate, and individuals may grow more vulnerable. Hospitals are unable to discharge patients that are medically fit because they don’t have the right care in place to return home. This puts pressure on hospital beds, causing blockages in A&E departments, resulting in ambulances spending hours on hospital forecourts with patients. Yet again, putting lives at risk. NHS England figures, obtained by GMB union through a freedom of information request, show deaths in ambulances have doubled in the last year and incidents where the patient suffered severe harm while in ambulance transit have tripled.12

Underinvestment has also resulted in declining outcomes for children and higher costs for the taxpayer. Effective early intervention in family life reduces the need for more expensive state intervention in later life. In 2021 the House of Lords Public Services Committee reported that between 2010/11 and 2019/20, local government spending on early intervention fell by 48 per cent to £1.8bn while spending on costlier, higher-intensity interventions like youth justice increased by 34 per cent to £7.6bn.13

As this example shows, our public services are a deeply interconnected ecosystem, underfunding in one area put strains on other areas too. Backlogs, delays and soaring unmet need have a material effect on people living in the UK and on our economy. As a nation, we are getting sicker, with average life expectancy falling in 2020 for the first time in 40 years.14

Workforce participation has fallen sharply, with over 500,000 working-age adults ‘missing’ from the workplace since the pandemic. Meanwhile, the number of working-age adults identifying as economically inactive due to long-term sickness rose by the same number - half a million to 2.5 million, up from 2 million over the same time period.15

Strong public services are the backbone of a strong and stable economy. Delivering that, requires effective and well-resourced public services, staffed by a valued and motivated workforce. Yet, key areas of the public sector are facing severe staffing shortages, following more than a decade of government-imposed real terms pay cuts for the workforce.

Nurses have lost £42,000 in real earnings since 2008 – the equivalent of £3,000 a year. For midwives and paramedics, the losses are more than £56,000 – the equivalent of £4,000 a year.16

In the education sector, teachers and school leaders have lost around a quarter of their pay since 2010 according to separate analysis by the NEU 17

, NASUWT 10

and NAHT.

New research published by the TUC found that around one million children with key worker parents are living below the poverty line, representing 19 per cent of children in key worker households.18"

The toxic mix of pay cuts, unsustainable workloads and low morale are forcing workers to leave in droves in search of better paid jobs. A TUC survey found one in three public sector workers have taken steps to quit or are actively considering doing so, with the majority citing pay as the main factor 19

Vacancy rates in health and social care have reached record highs at 10.5 per cent 20

and 10.7 per cent respectively. This is a worsening situation – 2021/22 saw the highest recorded annual vacancy rate in social care - 165,000 vacant posts, up 52 per cent from the previous year. 21

In education, retention rates have reached a historic low - just two-thirds of early-career teachers (67 per cent) remain in the profession after five years. 22

In local government, employers have warned a third of councils in England do not have the skilled staff needed to deliver key services. 23

While we have high vacancy rates and real terms pay cuts for public sector workers, we cannot get to grips with the issues facing our country. Staff shortages put huge strain on those who remain as they try to plug the gaps, fuelling excessive workloads and long working hours. This undermines the quality of our public services, and leads to high rates of attrition and absenteeism. These vacancies are hard to fill, due to the skilled nature of the work. High turnover costs the public purse, in the loss of knowledge drawn from years of hard work and experience, but also in the increasing reliance on agency staff as well as recruitment, induction and training costs.

There is also a strong economic case for investing in public sector pay, as we set out in the following section.

- 9 The Health Foundation (2022) How does UK health spending compare across Europe over the past decade

- 10 a b ADASS (2021) ADASS November 2021 Snap Survey Report. https://www.adass.org.uk/ snap-survey-nov21-rapidly-deteriorating-social-services

- 11 Association of Directors of Adult Social Services, Waiting for Care and Support, 13 May 2022, p. 5, www.adass.org.uk/media/9215/adass-survey-waiting-for-care-support-may-2022-final.pdf; Association of Directors of Adult Social Services, ‘ADASS Survey – adult social care: people waiting for assessments, care or reviews’, 4 August 2022, p. 3, www.adass.org.uk/media/9377/adass-survey-asc-people-waiting-for-assessments-care-or-reviews-publication.pdf.

- 12 GMB (2022) https://www.gmb.org.uk/news/ambulance-admission-and-transfer-deaths-more-double

- 13 House of Lords public services committee, ‘ Role of public services in supporting vulnerable children’, November 2021, p4

- 14 ONS (2021) National life tables – life expectancy in the UK - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

- 15 ONS (2022) Half a million more people are out of the labour force because of long-term sickness - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk)

- 16 TUC (2023) Patients overwhelmingly back striking NHS key workers – new TUC poll | TUC

- 17 NEU (2022) (neu.org.uk)

- 18" TUC (2022), 1 in 5 key worker households have children living in poverty (tuc.org.uk)

- 19 TUC (2022) https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/around-1-3-key-workers-public-sector-have-taken-steps-leave-their-profession-or-are-actively

- 20 NHS Digital (2022) NHS Vacancy Statistics (and previous NHS Vacancies Survey) - NHS Digital

- 21 Skills for Care (2022) https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/Adult-Social-Care-Workforce-Data/Workforce-intelligence/publications/national-information/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-in-England.aspx

- 22 House of commons library (2022) Teacher recruitment and retention in England (parliament.uk)

- 23 LGA (2023) 2022 Local Government Workforce Survey | Local Government Association

Challenging under any circumstances, the government have ensured workers could not be worse placed to handle the biggest inflation for 40 years. In December 2022 CPI inflation was 10.5 per cent and RPI 13.4 per cent. Food inflation is now 16.8 per cent, the highest for 45 years; and energy bills have increased brutally, with gas inflation at 129 per cent and electricity at 65 per cent.

The government’s current proposed response to this inflation is to impose the same austerity dogma, once more seeking to restrain spending on pay and public services, with the Chancellor promising “restraint on spending… to make a lower tax economy possible” in his recent Bloomberg speech.25

For more than a decade public sector workers have suffered government imposed cuts, freezes and caps, and now face even worse pressures as a result. As we saw from 2010 onwards, austerity simply delivered worse outcomes for the country as a whole:

- reduced public sector pay reduced spending in the economy

- reduced spending reduced economic growth overall,

- reduced economic growth resulted in lower private sector pay, and

- reduced economic growth and lower pay meant lower tax revenues, and

- the publics finances were not been repaired.

In January 2021 Laurence Boone, chief economist of the OECD, commended government stimulus in the wake of the global financial crisis, and warned: “The mistake came later in 2010, 2011 and so on, and that was true on both sides of the Atlantic … The first lesson is to make sure governments are not tightening in the one to two years following the trough of GDP”. 26

Beyond the false macroeconomics of austerity, the government makes various other arguments – these are discussed in Box A below.

Box A: The Treasury evidence to Pay Review Bodies

In addition to failed austerity imperatives, the Treasury make various other contentious claims in their latest evidence to the pay review bodies. Above all warnings of a wage-price spiral sit oddly with the idea that the “expected recession” will “contribute to normalisation of nominal pay growth”.

Not for the first time, there are appeals to the self-defeating notion of parity between public and private sector workers. In their own terms these amount to a mechanism for levelling down: public sector pay must be cut because of an alleged premium over private sector workers (their Figure 3.A). Today the claimed premium extends beyond pay to pension provision and job security. But any such appeal fails to account for the bonuses paid to workers in the private sector. TUC analysis of the financial and insurance sector found City pay rising six times faster than average wages.

Many authors have in the past contested these aggregate comparisons as inappropriate because of the different types of work in the public and private sectors. There is a wider range of pay in the private sector. Sectors such as finance and manufacturing enjoy a premium when compared with the public sector but overall earnings are pulled down by low pay in hospitality, catering and retail. Jobs in the public sector typically require higher level of qualification. Superficial pay comparisons fail to account for this and the different demographics between public and private sector workforces, such as age, gender, role and responsibilities.

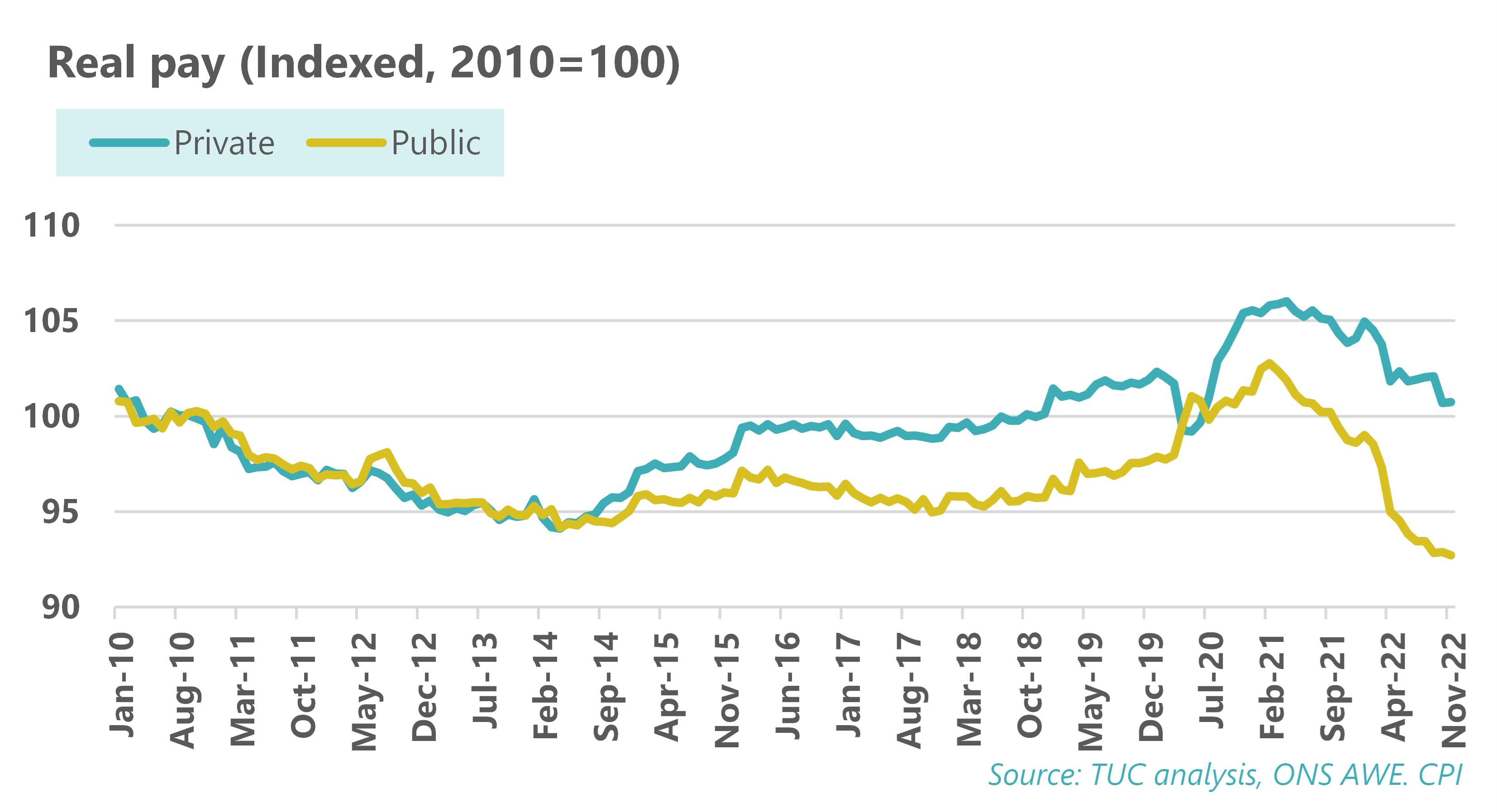

But, of course, attempts to level down public sector workers is equally counterproductive for private sector workers. The chart below shows the level of real pay in the public and private sectors indexed to 2010. As public sector pay was cut, private sector pay followed suit; conversely private and public pay moved up together from the bottom. The latest wage data shows private sector pay barely above the level it was 12 years ago, and currently declining. And public sector real pay has declined far beyond the previous lowest level.

With real pay collapsing at an unprecedented rate, the idea of a wage price spiral is only a danger in theory. Even their own assessment is very half hearted – “There is uncertainty around the magnitude of any wage –price spill overs in the public sector, but it is a risk the government cannot ignore” (para 3.10). As the Treasury separately argue, recession will wholly change the situation. Appealing to corresponding concerns at the Bank of England concerns does not make the situation a reality. Likewise citing the Bank for International Settlements support for policy, is another fear of a spiral in theory – and the BIS conceded “To date, there is limited evidence that most AEs are entering a wage-price spiral” (p. 5). The Treasury did not cite the IMF, who concluded: “Historical episodes in advanced economies exhibiting wage, price, and labor market dynamics similar to those of the current circumstances—in particular, economies in which real wages (nominal wages deflated by consumer prices) have been flat or falling—did not tend to show a subsequent wage-price spiral”.

Likewise the Treasury use of figures is selective, for example dwelling on settlement data rather than official data for private sector pay growth. More substantially the past has been erased. The pay review body “’uplifts’ for 2022-23 may have at the time been the highest “in nearly twenty years”, but inflation has got worse since the PRBs met and even more importantly the bar is a low one against the worse outcomes for 200 years.

The Treasury justly report the better earnings performance at the lower end of the pay distribution (Figure 3.D), but this follows at least in part increases to the minimum wage and reenforces the case for levelling up not down.

More generally many – including quite unexpected figures – have contested the wider economics of public sector spending and inflation. The former permanent secretary to the Treasury, cited a David Smith piece in the Sunday Times: “Public sector workers don't cause inflation: their wages lag the private sector's. The problem for HMG and its workers is that its public finance strategy rests on imposing the biggest real wage cuts in living memory”. Smith himself observes: “There is little danger that higher public sector pay settlements would trigger a wage-price spiral”. Willem Buiter, a founder member of the Monetary Policy Committee, went as far as “Thatcher would give massive pay rise to public sector workers”. Another founder member, Charles Goodhart, warned of “a year of discontent unless they agree a wage deal to end the ongoing industrial action.”

Even the Treasury use of trade union position is a misrepresentation. Current inflationary pressures may be a key factor in the ongoing industrial action, but this is far from the only reason. Likely the main reason is fifteen years of cuts that have ruined salaries and destroyed public services, and in certain areas the consequent risk to the public.

In effect policymakers are prioritising a spiral in theory over the very real threat of recession, and the immense damage it will cause not least to people who already can’t afford to live. Moreover even the theoretical conditions for a wage price spiral are different to the present situation. Fundamentally this is not the 1970s. Wages are following prices, and still at a good distance and certainly not spiralling. Workers are (in part) seeking to keep up with a sharp increase in the cost of living, not themselves forcing the standard of living higher. Labour is not motivated by greed but by hardship. The injustice is amplified given the vastness of wealth (section 6.c).

References

Bank for International Settlements; Wilhem Buiter on Bloomberg; Charles Goodhart;

HMT evidence; IMF World economic outlook; MacPherson; James Meadway, Open Democracy;

David Smith in The Times; TUC: City bonuses are rising six times faster than wages | TUC

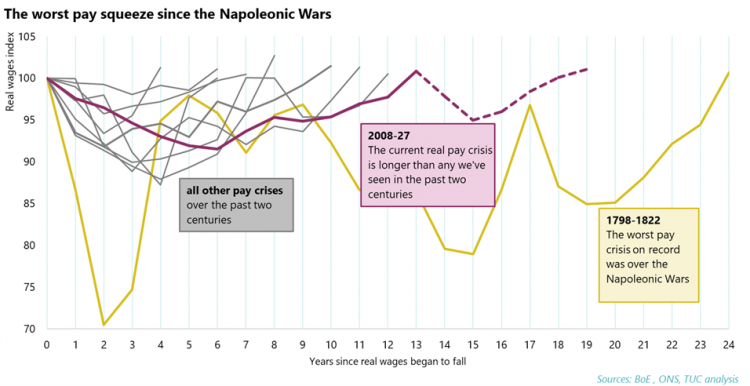

Overall, across both public and private sectors the impact of government policy is a severe real pay crisis. The chart below compares the current real pay decline with all other comparable episodes since the start of the nineteenth century. Even ahead of the present inflation, the current crisis was the worse since the Napoleonic Wars. Together the resumed declines in 2022 of 2.9 per cent and 2023 of 3.0 per cent are the steepest for fifty years (years 14 and 15 on the chart). On current forecasts (which have repeatedly proven optimistic – see section 6.c) the crisis is not expected to end until 2027, nineteen years after the start in 2008.

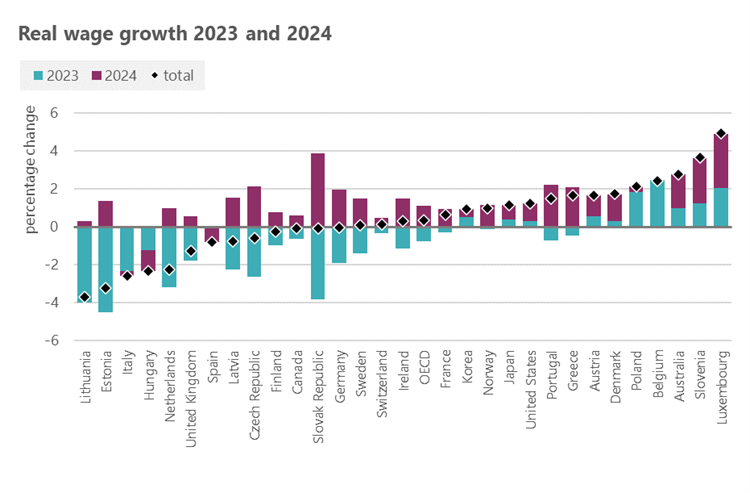

While pressures on prices are affecting all countries, the UK’s real pay performance is particularly bad. The ILO report that real wages fell in advanced G20 countries by 2.2 per cent in the first half of 2022, the first global decline since its records began.[1] They note that of G20 economies only Italy, Japan, Mexico and the UK have real pay below 2008 levels. And looking forward UK wages are under more pressure than most other advanced economies. The OECD forecasts a UK real wage decline from 2022 to 2024 of 1.3%, the sixth worse of the advanced economies on the chart below. 27

The OECD average is up 0.3% - the UK has both a steeper decline into 2023 and smaller rise into 2024.

- 27 ILO, Global Wage Report, 2022-23

In November 2022 public sector real pay fell by 6.7 per cent (on CPI), declining at twice the rate of private sector pay. As illustrated in section 3, this has led to recruitment and retention crises across the public sector.

A strong economy requires well-paid, secure workers. However, TUC analysis shows that 3.7 million people are in insecure work. 28

This includes those on zero-hours contracts, agency, casual and seasonal workers (but not those on fixed – term contracts) and the low-paid self-employed.

Ministers have failed to find Parliamentary time for a long-promised Employment Bill. But are pursuing other legislation that could undermine pay and conditions. The government has tabled the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Bill to give ministers the power to impose minimum service levels during industrial disputes in services within six broad sectors. This is despite its own impact assessment for a predecessor Bill that admitted it could lower terms and conditions, not only in affected services, but beyond them. 29

Likewise, the government is putting workers’ rights at grave risk, and threatening stability in the workplace by pursuing the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill.

This allows thousands of pieces of legislation that have their roots in EU law to be automatically revoked at the end of this year, unless Parliament passes statutory instruments to retain or restate them. It would also abolish three principles of EU law. Regulations covering agency workers, part-time workers and pregnant workers could be among the vital protections to be lost.

In other areas decades-worth of case law could be lost forcing employers and workers to turn to the legal system to clarify rights.

The lack of a strong framework of rights for workers was underlined by the widespread use of ‘fire and rehire’ tactics during the pandemic, where workers were asked to accept poorer terms and conditions or face the sack, and by the scandal at P&O Ferries, where 800 workers were fired without notice. Despite these egregious breaches of current law and common decency, the Boris Johnson government dropped its much trumpeted commitment to an Employment Bill.

Insecurities at work and the lack of worker protection has a disproportionate impact on those facing structural disadvantages in the workplace and beyond. As well as falling pay, the labour market is still characterised by significant pay gaps between men and women, disabled and non-disabled workers, and workers of different ethnicities.

The gender pay gap, while falling, remains high. Female employees are paid 14.9 per cent less than male employees, with the gap widening among age groups over 40 30

. Disabled employees are paid £2.05 per hour less than non-disabled employees 31

. The disability pay gap intersects with the gender pay gap, with the pay gap being wider among disabled women and non-disabled men. Median hourly pay for disabled women (£11.33) is £3.93 less than it is for non-disabled men (£15.25).

It’s not just pay. Women, Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers, and disabled workers all face other forms of inequality in the labour market. The unemployment rate is twice as high among BME workers as it is among white workers (6.9 per cent, compared to 3.2 per cent), and is higher still among BME women (8.1 per cent) 32

. BME workers are also more likely to be in insecure work 33

, and a recent TUC report found that two in five BME workers reported experiencing racism at work in the last five years 34

.

Disabled people face a higher unemployment rate and a lower employment rate than non-disabled people. The employment gap is 28.5 percentage points, and the unemployment rate for disabled workers is double what it is for non-disabled workers (6.8 per cent compared to 3.4 per cent) 35

. Labour market inequalities for BME and disabled workers combine. Disabled BME workers face an unemployment rate almost four times higher than the unemployment rate for non-disabled white workers (10.9 per cent compared to 2.8 per cent). The rate is highest among disabled BME women (11.3 per cent).

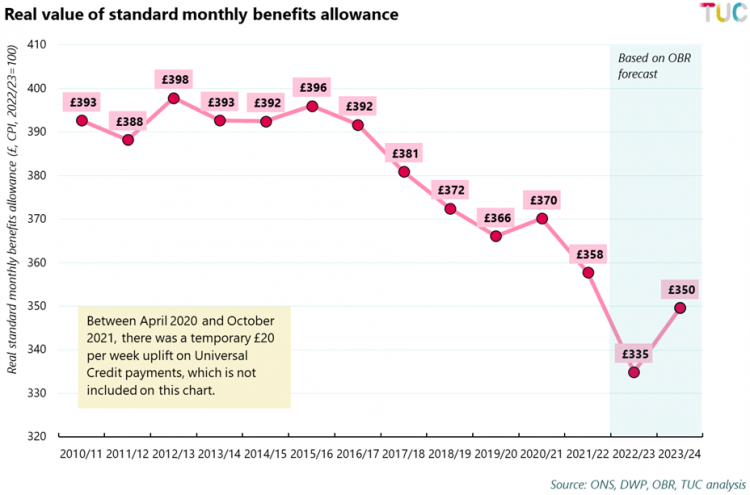

And while more workers face insecurity at work, government have also dramatically weakened the safety net. Cuts in social security since 2010 have left millions in poverty. The current levels of benefits are simply not enough to live on, and the rising cost of living is it making it even harder to survive on them. The standard benefit payment for over 25s without housing costs is £77 a week.

Since 2010/11, the real value of the standard benefits payment has dropped by £58 per month. Even with the uprating in line with September 2022 inflation set to come into effect this April, the real value of the standard payment will still be £43 per month lower than it was in 2010.

- 28 https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-why-employment-rights-need-overhaul

- 29 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1112717/transport-strikes-minimum-service-levels-bill-impact-assessment.pdf

- 30 Gender pay gap in the UK: 2022, ONS (2022). Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2022

- 31 Jobs and pay monitor - disabled workers, TUC (2022). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-pay-monitor-disabled-workers

- 32 A09: Labour market status by ethnic group, ONS. Figures used are from Jul-Sep 2022. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/labourmarketstatusbyethnicgroupa09

- 33 Insecure work – Why employment rights need an overhaul, TUC (2022). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-why-employment-rights-need-overhaul

- 34 Still rigged: racism in the UK labour market, TUC (2022). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/still-rigged-racism-uk-labour-market

- 35 Jobs and pay monitor - disabled workers, TUC (2022). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-pay-monitor-disabled-workers

Trussell Trust data for April to September 2022 shows they distributed 1.3 million food parcels to people facing hardship – this is an increase of 52% compared to the same period in 2019. Half a million of these parcels were distributed to children.36

New research by Joseph Rowntree highlights 7.2 million households are going without the basics, and this takes in to account the May 2022 energy support package provided. 37

Rising food costs and bills mean that much of the support – delivered through the emergency budget in May was used up on food: the Trussell Trust reported almost two-thirds (64%) of Universal Credit claimants had to spend July’s first Cost of Living Payment from the government on food. 38

No additional financial support has been given to children in the current cost of living crisis and yet nearly one in three children in the UK live in poverty. Analysis by the TUC, IPPR and CPAG shows increasing child benefit by £20 per week per child would reduce child poverty by 500,000, lifting a total of 700,000 people overall from poverty, at a cost of £9.9 billion. 39

Rather than temporary support schemes the Government needs to put in place permanent improvements to the levels of social security.

- 36 Almost 1.3 million emergency parcels provided in last 6 months - The Trussell Truste

- 37 Going under and without: JRF’s cost of living tracker, winter 2022/23 | JRF

- 38 Forty percent of people claiming Universal Credit skipping meals to survive, new research from the Trussell Trust reveals - The Trussell Trust

- 39 A lifeline for families: Investing to reduce child poverty this winter | IPPR

The government argue public sector pay restraint is necessary to control inflation, and have warned of the risk of so called ‘wage price spirals’ - despite the comprehensive evidence that these are not a cause of inflation in the UK, or a common response to inflationary environments. But as the forecasts of the Bank and the OBR show, inflation is likely to be brought down by recession. As recessionary pressures intensify, an economic policy based on austerity 2.0 will be highly dangerous.

a. Risk of recession and unemployment

In January 2023 the Bank of England (alongside other central banks) hiked rates for the eighth time, with the rapidity of increases greatly more forceful than anticipated when the policy began. Reporting World Bank analysis, Martin Wolf shows “The current monetary tightening in the G7 is expected to be the strongest since the early 1980s”.40

In the UK the interest rate has increased from 0.1 per cent to 3.5 per cent. Huw Pill the Bank’s chief economist describes the actions as making “significant progress in the normalisation of the monetary policy stance”.41

Since the Bank of England’s November forecast and the OBR Autumn forecast, policymakers have considered the UK economy in recession. The latest Treasury evidence to the pay review bodies states “The economy contracted by 0.2% in 2022 Q3, and the OBR do not expect this recession to end until 2023 Q4, with a peak to trough fall of 2.1%”. The Bank of England in their November forecast were reckoning on something significantly worse (peak to trough fall of minus 2.9 per cent). While the monthly data have been erratic (because of the late Queen’s Jubilee and funeral, and then the world cup), and the latest outturn for November 2022 up slightly, the three-monthly growth rate is still down 0.3 per cent.

Correspondingly the labour market may be at a turning point. The unemployment rate rose to 3.7 per cent over Sep-Nov 2022, from a low point of 3.5 per cent in Jun-Aug, but the position is still better than 4.0 per cent ahead of the pandemic (Dec -Feb 2020). The employment rate is little changed over recent quarters and stands at 75.6 per cent in Sep-Nov 2022, but well down on the pre-pandemic rate of 76.6 over Dec -Feb 2020. Outside the headline figures, total hours worked have fallen for two quarters (by a total of 1.0 per cent); and vacancies have fallen for 7 consecutive months, from 1,300,000 to 1,161,000 (by 10.7 per cent). Beyond the outturn figures, the Bank of England and OBR are both forecasting a rise in unemployment, the former by one million and the latter by half a million. The widened gap between employment and unemployment since the pandemic is matched by a corresponding and widely discussed increase in inactivity. Measures to help more people get the jobs they want are essential. But with recession looming the demand for labour will fall; the Bank of England finds “some indication that the demand for labour has weakened”.44

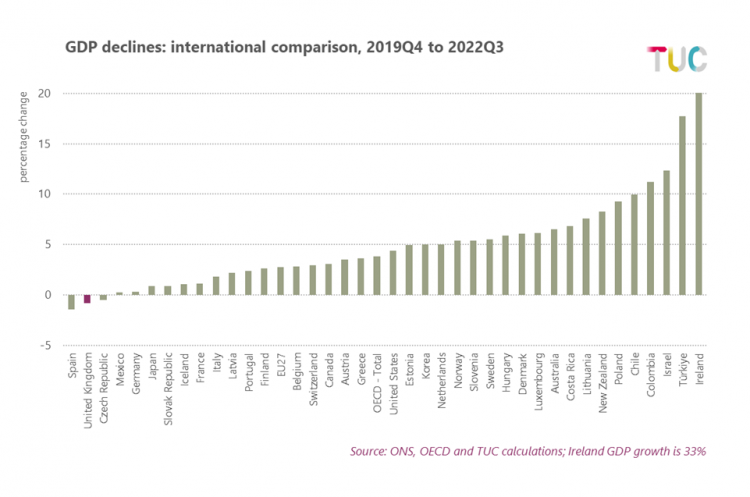

On an international view of GDP outcomes since the start of the pandemic the UK is second to last of all advanced economics, and one of only three where in 2022Q3 GDP was still below the pre-pandemic level.

- 40 https://www.ft.com/content/17f5fcb0-b734-4c29-8b25-52b5597701a3

- 41 https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2023/january/huw-pill-chair-and-general-discussant-at-the-american-economics-association-annual-meeting

- 44 Monetary Policy Report, Nov. 2022: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2022/november-2022

But the likelihood of recession is far from unique to the UK. The World Bank’s annual ‘Global Economic Prospects’ warns that the world is "perilously close to falling into recession”. 43

b. The policy response to date

Policymakers justly point at Putin’s illegal war and supply bottlenecks as the cause of inflation, but the policy reaction belongs to central banks and other policymaking institutions. In the UK, it belongs also to government. In October 2022, at the annual meeting of the IMF and World Bank, Director-General Kristalina Georgieva warned:

- Policymakers have an incredibly narrow path to walk—there is no room for missteps. Get it wrong and the challenges of the present could mutate into worse problems – prolonged low growth, entrenched inflation, or even sovereign debt crises with the risk of contagion.

She also observed that the weakest have been hit hardest:

- More than 60 percent of low-income countries and over 25 percent of emerging markets are in or at risk of debt distress. This will only get worse if interest rates rise further, the dollar gets stronger, and capital outflows increase. 44

As discussed in Box A, fiscal and monetary policy action is motivated less by inflation itself and more by the threat of wage–price spirals – yet these spirals are not evident. Huw Pill talks of the UK situation specifically as exceptional, but, as shown above, UK real wage growth is now, and expected to continue to be, among the lowest of all advanced economies.

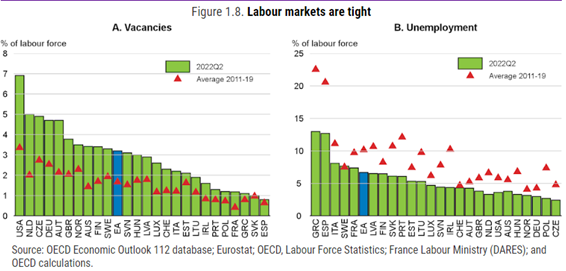

More generally there is very limited evidence that conventional measures of tightness indicate disproportionately higher wage inflation. In their latest Economic Outlook, the OECD show comparisons between the latest and longer-run (average over 2011-19) outcomes for vacancies and unemployment. On both of these standard measures of ‘tightness’ (OECD figures shown below), the UK (here ‘GBR’) is showing higher pressures than most countries – with higher-than-normal vacancies and lower-than-normal unemployment.

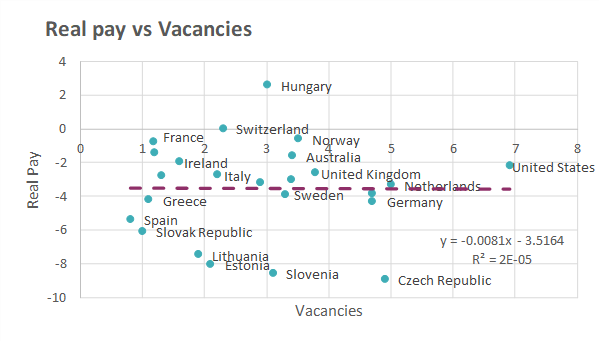

The same section of the Economic Outlook also includes a more up to date quarterly measure of real wage inflation (year to 22Q3, Figure 1.9). The charts below compare these figures with the measures of labour market tightness. Specifically for the UK, while both measures indicate one of the tightest labour markets real wages are firmly in the middle of country outcomes. More generally across all OECD countries vacancies have increased significantly, yet this measure of real pay has still fallen in all countries except Hungary. Moreover it is not the case at the moment that higher vacancies are associated with higher pay growth, the correlation is zero when comparing between OECD countries.

The same results follow on the unemployment measure. Across all countries there is only the slightest evidence that low unemployment is associated with less bad pay outcomes. And any relationship that exists is nullified if Hungary, Greece and Spain are ignored as outliers.

The results echo previous TUC analysis looking at wage growth against labour market tightness by industry in the UK. This also found very little correlation between the industries getting pay rises and the level of labour market tightness measured by vacancy rates. 45

Tight labour markets do not automatically lead to wage rises, particularly in a context where workers’ power to negotiate through their trade unions has been under attack. Employers have been reluctant to respond to labour shortages with the kind of pay increases workers need – except where these have been negotiated by unions. Since the Autumn Statement the main risk is shifting increasingly from inflation to recession. Under these conditions protecting workers from inflation, will also serve to support the economy by sustaining expenditure. Doing the reverse will worsen the recession.

c. Austerity 2.0 and the doom loop in GDP

Thirteen years on, the failure of the government approach to macroeconomic policy is undeniable. As economists Jo Michell and Rob Jump demonstrated in a paper before the Autumn Statement, the rhetorical device of a ‘black hole’ in the public finances is not reflected by the economic reality. 46

A paper issued alongside this submission for a TUC conference outlines the wider and more devastating doom loop process. 47

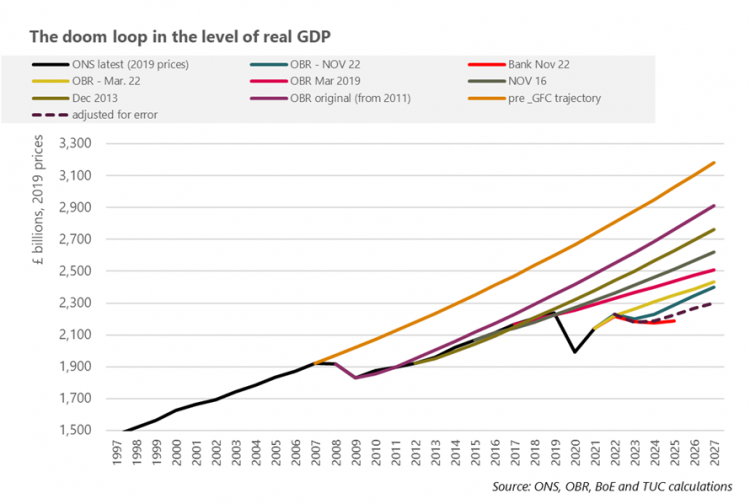

The chart below shows various iterations over time of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast (and the Nov. 22 forecast by the Bank of England). The latest projection for real GDP (in blue) shows the size of the economy in 2023 is expected to be £2.2 trillion (in 2019 prices); this is £400bn or one sixth smaller than a projection of the OBR forecast made in 2010 (in purple). If the economy had followed the pre-global financial crisis trajectory (from 1981, in orange), the size of the UK economy in 2027 would be £3.2 trillion.

- 45 JobsandrecoverymonitorPAY2.pdf (tuc.org.uk)

- 46 ‘The dangerous fiction of the “fiscal black hole”’, Rob Calvert Jump and Jo Michell, 10 Nov. 2022, https://progressiveeconomyforum.com/publications/the-dangerous-fiction-of-the-fiscal-black-hole

- 47 Text for footnote

This dysfunction has been progressively intensifying since Chancellor Osborne began austerity policies in 2010. With only a handful of exceptions, each OBR forecast for the level of real GDP is worse than the previous one (for clarity not all forecasts are shown on the chart). The OBR recognise uncertainty in their forecasts, but there is very little uncertainty here: over time forecasts are revised down.

According to the ‘doom loop hypothesis’, this is because the mechanisms at play – inadvertently perhaps – contain the expansion of the economy. Adjusting the forecast for the average downgrade suggests by 2027 the outturn will be £2.3tn, £900 billion lower than the pre-crisis trajectory.

A full account of the hypothesis is included in the TUC report; the essential steps were outlined in section 4 above, and illustrated on the graphic below. Critical to the doom loop is also the idea that at each iteration, the OBR wrongly attribute the reduced growth to a failure of supply (productivity) rather than demand (austerity).

The public finances will get worse not better without change. TUC have shown austerity 1.0 led to the weakest recovery and worse public finance outcome for 100 years. The pay crisis is then a result of the economic crisis.

But we were not ‘all it together’ as originally claimed. Alongside Congress 2022 TUC issued a report showing that the global financial crisis, dividends have increased three times faster than wages 48 . In spite of the usual rhetoric around hard decisions, at the Autumn Statement the Chancellor managed to lift a corporation tax surcharge for banks and the Prime Minister is still seeking to remove the bonus cap for bankers. New TUC analysis shows a record year for bankers’ bonuses, accounting for £18.7bn in the finance and insurance industry. 49 The figure is well above estimates for the costs of an inflation busting pay rise for public sector workers. 50

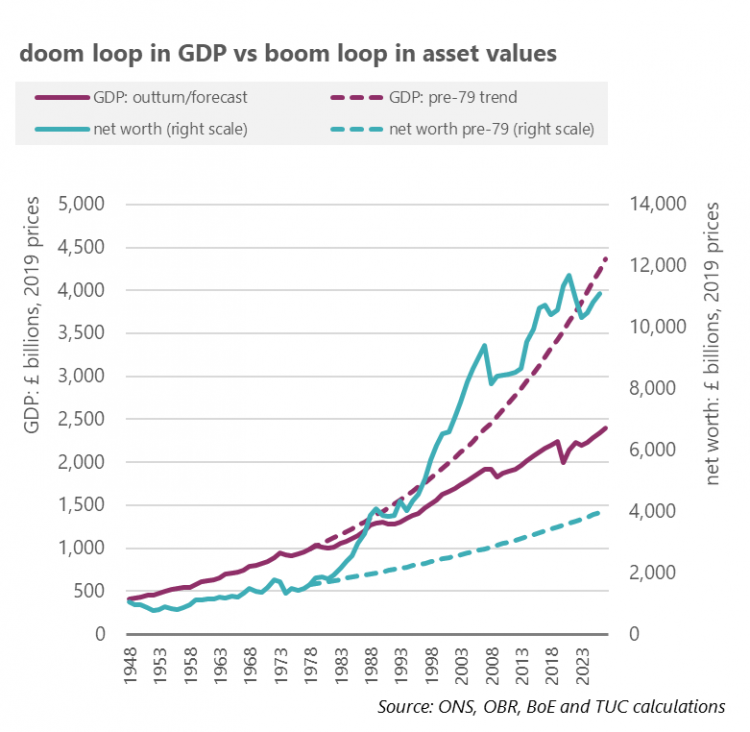

In the new report we show a longer view of the dislocation between wealth and labour. The chart below compares the doom loop in GDP outcomes, against a so-called ‘boom loop’ in asset values. 51

- 48 TUC (2022) Companies for People – How to make business work for workers

- 49 https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/city-pay-has-risen-more-three-times-faster-nhs-key-worker-pay-2008

- 50 In a discussion of Treasury estimates, the BBC report the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggesting the cost is “more like £14 billion”: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/63917967

- 51 Source: see n. 47

pre-1979 trend:

- GDP will have lost £2tn or nearly half the ground compared to the previous trajectory and

- wealth will have gained £7tn, or by more than three times.

These vast asset gains are matched at a global level by parallel increases in private and public indebtedness across the world. With this balance sheet expansion not supported by production, there is a significant risk that the present arrangement is unsustainable.

The paper outlines the alternative macroeconomics of an economic model with the balance reset in favour of work and away from wealth. These policies have a substantial international dimension, given wealth inequalities and failures of work are no less apparent between as well as within countries. Europe and North America account for ten per cent of the world population but 57 per cent of global wealth. Issued for the media circus around Davos, Oxfam report the richest 1% have pocketed $26 trillion (£21 trillion) in new wealth since 2020, nearly twice as much as the other 99 per cent of the world’s population. 52

The government appears set on attempting to cut its way to growth. But the evidence of the last decade shows that this is a disastrous strategy. Government’s first priority in the Spring Budget must be to resolve the ongoing pay disputes in the public sector, delivering real terms pay rises for the workforce and ensuring wages are rising across the economy:

Action to boost pay across economy

The real wage crisis facing the UK lies at the heart of the cost of-living crisis. Government must set out a plan to address it that includes:

- Fully-funded real terms pay rises for public sector workers, that protects them from the soaring cost of living and ensures we retain and recruit the skilled staff our public services urgently need.

- Increase the minimum wage to £15 an hour as soon as possible.

- Strengthen and extend collective bargaining across the economy, including introducing fair pay agreements to set minimum pay and conditions across sectors.

- Ensure all outsourced workers are paid at least the real Living Wage and receive pay parity with directly-employed staff doing the same job.

- Strengthen the gender pay gap reporting requirements, and introduce ethnic and disability pay gap reporting, requiring employers to publish actions plans on what they are doing to close the pay gaps they have reported.

- Ban zero hours contracts, tackle fire and rehire, and protect and enhance employment rights that derive from the EU, including strengthening workers’ rights to join and be represented by a union.

Invest in decent public services, funded by fair taxation

Building world class public services are essential for economic growth and prosperity. Government must take action to:

- Deliver fair and sustainable funding for public services. In the context of high inflation, ageing population and increasing demand, we cannot continue to cut back on public spending. We need to invest to grow and deliver the strong and resilient public services our country needs.

- Fix the public sector’s recruitment and retention crisis. A public sector jobs drive would ensure employment levels remain strong during the current economic downturn. TUC previously calculated we need an additional 600,000 staff to get back to strong and resilient public services that families can depend on.

- Deliver a new deal for social care, starting with a new sectoral minimum wage of £15 per hour for the workforce. This should be backed up by a funding settlement that fully offsets the cuts of the past decade and establishes future rises at a level that allows local authorities to meet rising demand for services.

- Introduce universal, flexible, high-quality childcare that is available to all from the point at which paid maternity or parental leave ends. This would ensure every family has access to affordable, flexible, high-quality childcare and that no one is worse off because they work and need to use childcare.

Tax changes must ensure that those with the broadest shoulders pay their fair share in this national effort. This should include:

- Higher windfall tax on excess oil and gas and energy company profits, with less exemptions and loopholes, in order to fund the Energy Price Guarantee and measures to future-proof homes

- Equalising capital gains tax rates with income tax rates, as a first step in ensuring that wealth is taxed fairly.

Action to better protect workers from hardship

Government must strengthen the energy price guarantee and introduce fairer energy tariffs, accelerate the roll-out of energy efficiency programmes, put in place a permanent short-time working scheme, and as well as temporary support schemes the Government needs to put in place permanent and improvements to the levels of social security.

- Cancel the energy price hike. The Energy Price Guarantee must not be increased from £2,500 from April 2023 onwards, and should be reduced to £2,000.

- Accelerate the introduction of permanent targeted measures to reach those most in need, including a social tariff for energy use capped at 5% of income for low-income households, and by restructuring tariffs to provide all households with an initial free energy allowance alongside an increase in the cost per unit for high-consumption households. This would incentivise energy savings but not penalise poorer low-consumption households.53

- Redirect underspend from the Energy Price Guarantee to domestic energy efficiency improvements with a retrofitting programme delivered in-house by local and regional public bodies, who have demonstrated the best ability to roll-out energy efficiency programmes through the Local Authority Delivery mechanism. Making our homes warm in the winter will slash the UK’s imports of fossil gas, helping both the national economy and millions of families,54

and defusing future supply crises.

- Take further action to prevent job losses due to high energy costs, both in energy-intensive industries and other sectors. Support for businesses to operate should not be hand-outs, but tied to good governance, workers’ rights and decarbonisation.

- Implement a short-time work scheme, building on the success of furlough to ensure that we can preserve employment during the pandemic –as the TUC set out in a report in 202155

.

- Increase universal credit and legacy benefits to 80 per cent of the real living wage. Scrap the benefit cap, along with the punitive two child limit in universal credit and legacy benefits, immediately.

- Provide financial support to children through child benefit. Increasing child benefit by £20 per week per child would reduce child poverty by 500,000, lifting a total of 700,000 people overall from poverty, at a cost of £9.9 billion.56

- Maintain the State Pension triple lock. In the short term, it is essential to ensure that the state pension at least rises in line with inflation to protect pensioner households from price increases. The need is particularly acute as retired households on average spend a greater proportion of outgoings than non-retired households on essentials like heating and fuel, and because the decision to suspend the triple lock for 2022/23 reduced incomes by up to £487 a year.57

In the long-term, the triple lock is still necessary to bring the UK state pension up to the OECD average.

Action to ensure decent jobs and growth for everyone

Efforts to induce business to invest in the economy through ever greater tax cuts have comprehensively failed. Instead we need to change the rules to encourage a long-term approach to delivering decent jobs and growth. That should include:

- Corporate governance reform to promote long-term sustainable investment and organic growth, rather than short-term focus on shareholder returns. Directors’ duties should be reformed so that directors are required to promote the long-term success of the company as their primary aim, taking account of the interests of stakeholders including the workforce, shareholders, local communities and suppliers and the impact of the company’s operations on human rights and on the environment. And company law should require that elected worker directors comprise one third of the board at all companies with 250 or more staff.

- Investment in the secure green energy future we need. Energy is expensive in the UK because of our broken energy system and dependence on volatile imported fossil fuels. The TUC has set out a plan to grow a new publicly-owned clean generation champion, in line with best practice in most other developed countries,58

to take our retail energy companies into public ownership, and to rapidly scale up investment into a secure net zero carbon energy mix.59

- Rebooting our skills system through a new national lifelong learning and skills strategy. The TUC is calling for a new national lifelong learning and skills strategy based on a vision of a high-skill economy, where workers can quickly gain both transferable and specialist skills to build their job prospects. Delivering this would require:

- A significant boost to investment in learning and skills by both the state and employers. People should have access to fully-funded learning and skills entitlements and new workplace training rights throughout their lives, expanding opportunities for upskilling and retraining.

- These entitlements should be incorporated into lifelong learning accounts and accompanied by new workplace rights, including a new right to paid time off for learning and training for all workers.

- Create a new national social partnership on skills – led by employers and unions – to provide clear strategic direction, as in the case of most other countries. This should include renewed support for union learning.

- And the government should reverse the counter-productive decision to cut the funding for UnionLearn.

- A significant boost to investment in learning and skills by both the state and employers. People should have access to fully-funded learning and skills entitlements and new workplace training rights throughout their lives, expanding opportunities for upskilling and retraining.

Promote good jobs and protect workers’ rights

To boost domestic manufacturing, services and technology development, and reap the full benefit of developments in infrastructure and renewable energy, the government should adopt strong trade and procurement policies to strengthen local supply chains and raise employment standards.

- Use local content requirements where they are legal and needed, learning from US practices in the Inflation Reduction Act.

- Trade deals and WTO rules should be used as a lever to lock in the highest standards of workers’ rights by enforcing respect for International Labour Organisation conventions.

- Uphold the Level Playing Field and Paris Agreement compliance commitments in the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation agreement to maintain high standards of workers’ and trade union rights. The government must drop the Retained EU Law bill that would scrap the majority of retained EU workers’ rights and the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) bill that would deprive workers of the right to strike.

- Ensure the Good Friday Agreement is protected and avoid a trade war with the EU by respecting the Northern Ireland Protocol.

- Refrain from agreeing trade deals with human rights abusers such as Gulf States, India and Israel – these drive a race to the bottom on workers’ rights globally.

- 53 See TUC (2022) ‘A fairer energy system for families and the climate’ https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/fairer-energy-system-families-and-climate

- 54 See TUC (2022) ‘A fairer energy system for families and the climate’ https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/fairer-energy-system-families-and-climate

- 55 See TUC (2021) Beyond furlough: why the UK needs a permanent short-time work scheme at https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/beyond-furlough-why-uk-needs-permanent-short-time-work-scheme

- 56 A lifeline for families: Investing to reduce child poverty this winter | IPPR

- 57 https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/government-must-reverse-decision-suspend-pensions-triple-lock-amid-cost-living-crisis-tuc

- 58 See TUC (2022) ‘Public ownership of clean power: lower bills, climate action, decent jobs‘ https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/public-ownership-clean…

- 59 See TUC (2022) ‘A fairer energy system for families and the climate’ https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/fairer-energy-system-families-and-climate

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox