Jobs and pay monitor - disabled workers

We knew before the pandemic that disabled workers face both a disability pay gap and a disability employment gap.[1]

The disability pay gap is the difference between the median hourly pay of disabled and non-disabled people, and the disability employment gap is the difference between the employment rates of disabled and non-disabled people.

This means that disabled workers are less likely to have a paid job and when they do, they earn substantially less than their non-disabled peers.

This note builds on our previous research into these gaps.

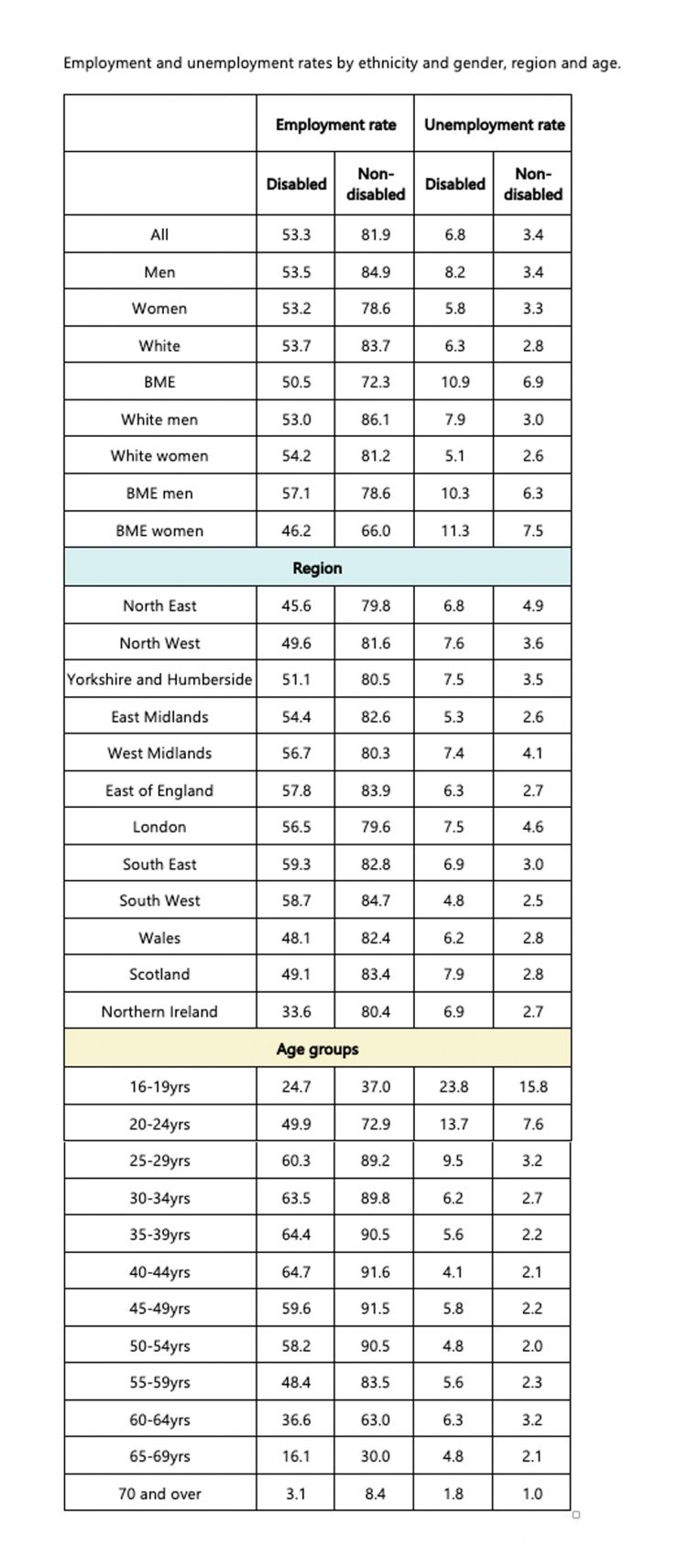

Disabled people face a higher unemployment rate and a lower employment rate than non-disabled people. The employment gap is 28.5 percentage points, and the unemployment rate for disabled workers is double what it is for non-disabled workers (6.8 per cent compared to 3.4 per cent). When disabled people are in work, they’re paid less. Median pay for non-disabled employees is £2.05 per hour (17.2 per cent) higher than it is disabled employees.

We know everyone is struggling right now, but disabled workers are facing this crisis with less money in their pockets and often higher than average household costs[2]. It’s no surprise that disabled workers are finding it harder to pay their bills[3].

Methodology

Our labour market analysis is based on the Labour Force Survey Q3 2021 to Q2 2022 (referred to as 2021/22). This period has been chosen as it makes use of the most recent data, and allows for comparison with our previous analyses. When relevant, we refer to quarterly data, but this data is not seasonally adjusted so comparisons can only be made between the same quarter in previous years.

Pay

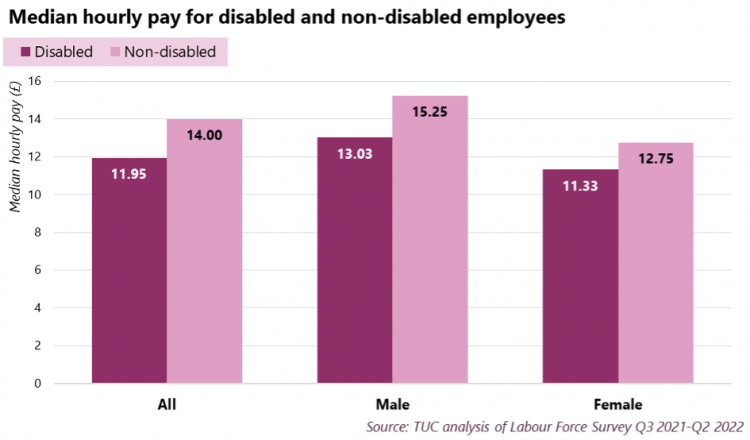

The pay gap between disabled and non-disabled employees in 2021/22 is £2.05 per hour. This means that non-disabled employees are paid 17.2 per cent more than disabled employees.

This has widened slightly since 2020/21, when median hourly pay for non-disabled employees was £1.90 (16.5 per cent) higher than it was for disabled employees. However, as we explained last year, we are currently cautious about drawing conclusions from changes in the gap due to issues with pay data during the pandemic, which likely affected some of last year’s 2020/21 analysis.

The gap is narrower than it was in 2019/20, when it was 20 per cent. But it remains higher than it was in 2017/18 and 2018/19, when the gap was 15.2 per cent and 15.5 per cent respectively.

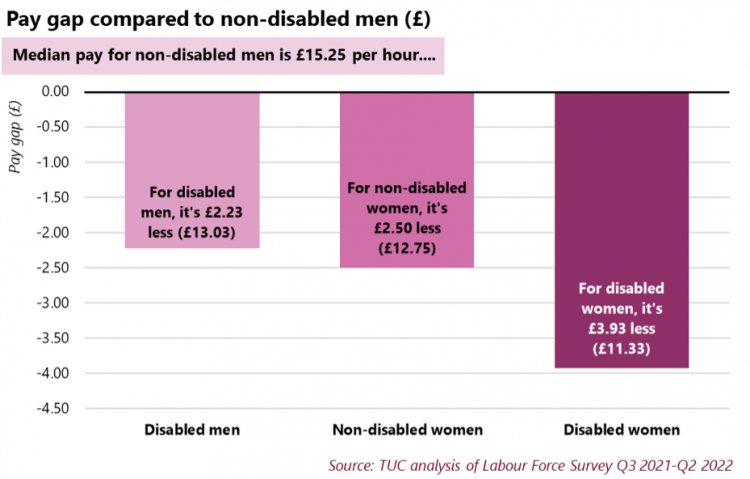

Gender and disability

The disability pay gap intersects with the gender pay gap, with the pay gap being wider among disabled women and non-disabled men. Median hourly pay for disabled women (£11.33) is £3.93 less than it is for non-disabled men (£15.25).

This is wider than last year, when median hourly pay for disabled women was £11.10, compared to £14.60 for non-disabled men – a pay gap of £3.50 per hour. Again, year-on-year comparisons should be treated with caution.

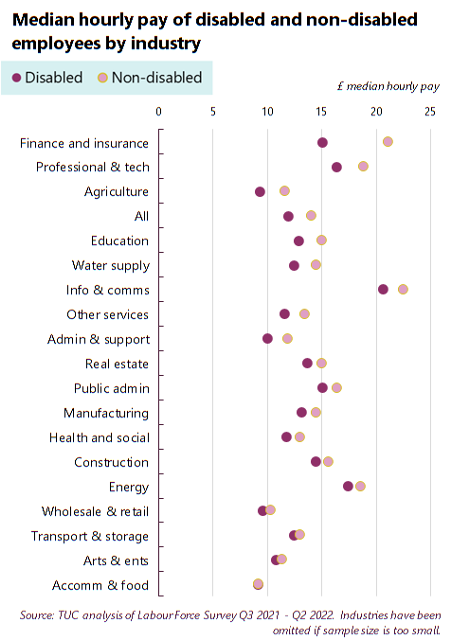

Pay gaps by industry

The pay gap also varies substantially by industry. The highest pay gap, by far, is in the finance and insurance industry, where non-disabled employees earn £5.90 per hour more than disabled employees. Two other industries have pay gaps larger than £2.05 (the all-employee gap): professional, scientific and technical services (£2.35) and agriculture (£2.25).

In every industry except one, disabled employees are paid less than non-disabled employees. The exception to this is accommodation and food, where disabled employees are paid 5p per hour more. It’s worth noting that pay in this industry is low for all employees, with median hourly pay of £9.18 for disabled employees and £9.13 for non-disabled employees.

Pay gap by age

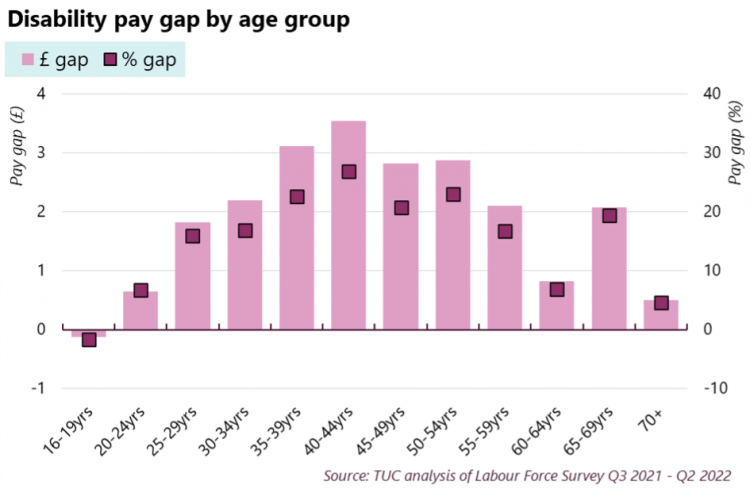

The disability pay gap is present among all age groups aged 20 and over, and peaks among those aged 40-44 years old (£3.55).

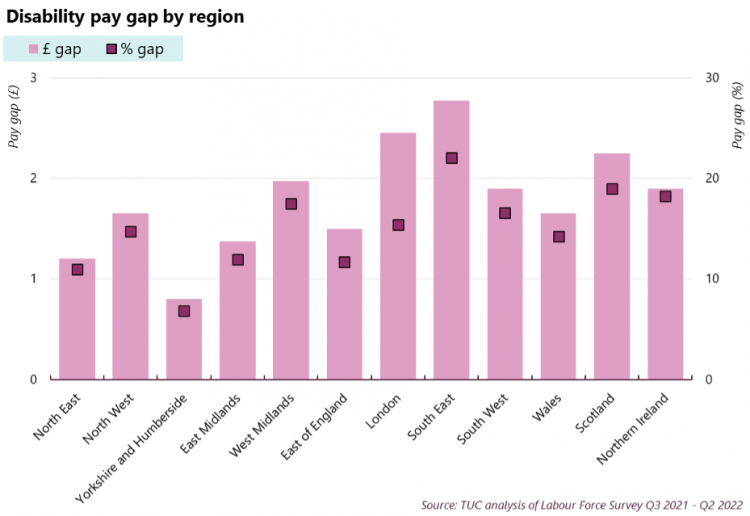

Pay gap by region

The disability pay gap exists in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, as well as every region in England. The gap is widest in South East England, where median hourly pay for non-disabled employees is £2.78 (22 per cent) higher than it is for disabled employees.

Employment

Employment gap

The employment gap is the percentage point gap between the employment rates of disabled and non-disabled people.

In 2021/22, the employment rate for disabled people was 53.3 per cent, compared to 81.9 per cent for non-disabled people. This gives an employment gap of 28.5 percentage points (ppts). This is a very slight narrowing compared to last year (2020/21) when the gap was 28.7 ppts.

While the gap has plateaued for a few years, it is around four and a half ppts lower now than it was ten years ago. In Q2 2013, the employment gap was 33.1 ppts[1].

As explained in last year’s report, however, there is growing evidence that suggests that the narrowing in the disability employment gap since this time is heavily accounted for by the expansion in disability prevalence and not primarily by a reduction in underlying disability employment disadvantage[1]. Research by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) estimates that disability prevalence accounts for half of the increase in the number of disabled people in employment between Q2 2013 and Q2 2021[2].

Unemployment gap

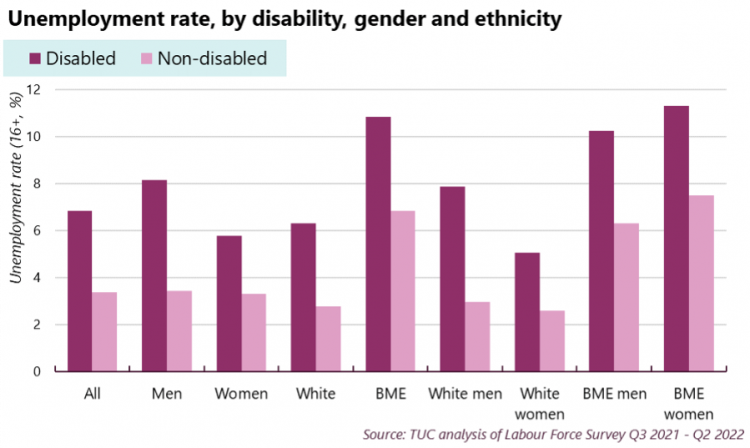

As well as a lower employment rate, disabled workers face a higher unemployment rate than non-disabled workers. In 2021/22, the unemployment rate for disabled workers is double what it is for non-disabled workers (6.8 per cent compared to 3.4 per cent).

Someone is considered unemployed if they are without a job, have been actively seeking work in the past four weeks and are available to start work in the next two weeks. A higher unemployment rate suggests that disabled workers who are actively seeking work are less likely to be employed.

Previous TUC analysis has looked at how Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers face a higher unemployment rate than white workers[3]. The chart below shows how the labour market inequalities for BME and disabled workers combine. Disabled BME workers face an unemployment rate almost four times higher than the unemployment rate for non-disabled white workers (10.9 per cent compared to 2.8 per cent).

Disabled workers face a higher unemployment rate and lower unemployment rate in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, as well as every region in England.

Disabled workers by occupation and industry

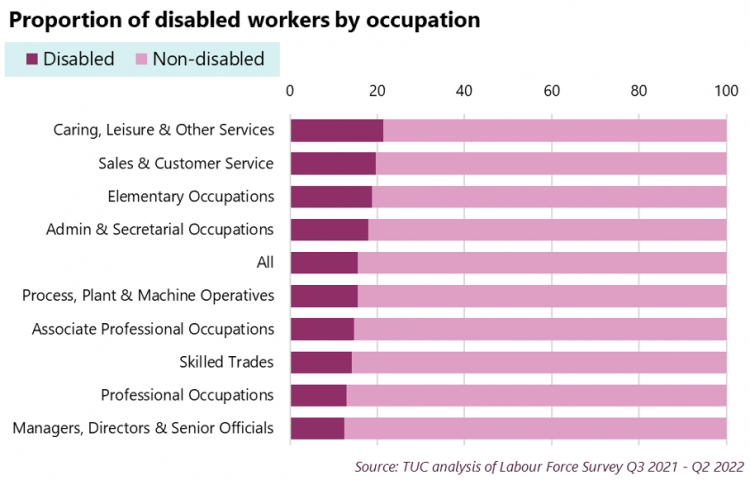

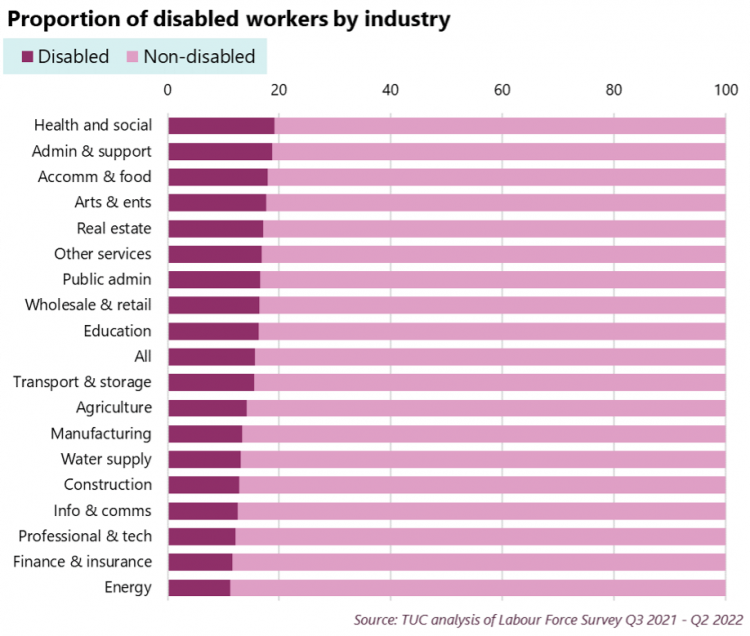

Disabled workers are over-represented in low-paid occupations and industries and under-represented in high paid occupations and industries.

Disabled workers make up 16 per cent of all workers, but only 12 per cent of managers, directors and senior officials and 13 per cent of those working in professional occupations. In contrast, around one-in-five workers in low-paid occupations such as caring, leisure and other service occupations (21 per cent), sales and customer service occupations (20 per cent), and elementary occupations (19 per cent) are disabled.

The same trend is true when we look at an industry breakdown. Disabled workers are over-represented in relatively low-paid industries such as health and social care (19 per cent), admin and support services (19 per cent), hospitality (18 per cent) and arts and entertainment (18 per cent), and under-represented in higher paid industries such as energy, finance and professional services.

This is likely one of the reasons behind the disability pay gap, and improving pay in these occupations and industries would help to narrow the gap.

Recommendations

Disabled people are always hit hardest, during the financial crisis, the pandemic and now the cost-of-living emergency. We need change now.

The trade union movement is calling on the Government to bring in mandatory disability pay gap reporting for all employers with more than 50 employees.

The legislation should be accompanied by a duty on employers to produce targeted action plans identifying the steps they will take to address any gaps identified. And we’re calling for the same for gender, ethnicity and LGBT+ identities because we cannot end inequalities in pay for one group without ending them for all.

We also need to address the underlying causes of the pay gap. Disabled workers are more likely to be in part time work, in lower paid jobs and in insecure work, or excluded from the jobs market entirely. The pay gap is also linked to unlawful discrimination, a lack of access to flexible working, and employers failing to provide reasonable adjustments.

That’s why we also demand:

- The National Minimum Wage to be raised to £15 an hour as soon as possible and a real pay rise for public sector workers.

- A ban on zero-hours contracts by giving workers a right to a contract which reflects their normal hours of work.

- A day one right to flexible working for all workers and a duty on employers to advertise possible flexible working options in job adverts.

- Specific ring-fenced funding for the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) to effectively enforce disabled workers’ rights to reasonable adjustments. The EHRC must update their statutory code of practice to include more examples of reasonable adjustments, to help disabled workers get the adjustments they need quickly and effectively.

- A stronger legal framework for reasonable adjustments including: ensuring employers respond quickly to requests, substantial penalties for bosses who fail to provide adjustments and for reasonable adjustment passports to be mandatory in all public bodies.

- That the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Disabled Persons (UNCRPD) be incorporated into UK law.

- An end to attacks on the right to strike so Disabled workers and all workers can defend and improve their pay and conditions.

The TUC has made additional recommendations on how to address the disability employment and pay gaps, which can be found in our 2019 report on disabled workers experiences in the pandemic[1].

Improving the benefits system

While actions can be taken to help disabled people who want to work get into and stay work, some disabled people are unable to work. It’s therefore important to have a supportive welfare system to support people out of work.

We do not currently have this. The welfare system has been worsened by the introduction of Universal Credit. We believe that the policy and design of Universal Credit is fundamentally flawed and have set out a replacement for the system[2].

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox