Spring Budget 2023

A strong economy requires well-paid, secure workers. However, TUC analysis shows that 3.7 million people are in insecure work. 28

This includes those on zero-hours contracts, agency, casual and seasonal workers (but not those on fixed – term contracts) and the low-paid self-employed.

Ministers have failed to find Parliamentary time for a long-promised Employment Bill. But are pursuing other legislation that could undermine pay and conditions. The government has tabled the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Bill to give ministers the power to impose minimum service levels during industrial disputes in services within six broad sectors. This is despite its own impact assessment for a predecessor Bill that admitted it could lower terms and conditions, not only in affected services, but beyond them. 29

Likewise, the government is putting workers’ rights at grave risk, and threatening stability in the workplace by pursuing the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill.

This allows thousands of pieces of legislation that have their roots in EU law to be automatically revoked at the end of this year, unless Parliament passes statutory instruments to retain or restate them. It would also abolish three principles of EU law. Regulations covering agency workers, part-time workers and pregnant workers could be among the vital protections to be lost.

In other areas decades-worth of case law could be lost forcing employers and workers to turn to the legal system to clarify rights.

The lack of a strong framework of rights for workers was underlined by the widespread use of ‘fire and rehire’ tactics during the pandemic, where workers were asked to accept poorer terms and conditions or face the sack, and by the scandal at P&O Ferries, where 800 workers were fired without notice. Despite these egregious breaches of current law and common decency, the Boris Johnson government dropped its much trumpeted commitment to an Employment Bill.

Insecurities at work and the lack of worker protection has a disproportionate impact on those facing structural disadvantages in the workplace and beyond. As well as falling pay, the labour market is still characterised by significant pay gaps between men and women, disabled and non-disabled workers, and workers of different ethnicities.

The gender pay gap, while falling, remains high. Female employees are paid 14.9 per cent less than male employees, with the gap widening among age groups over 40 30

. Disabled employees are paid £2.05 per hour less than non-disabled employees 31

. The disability pay gap intersects with the gender pay gap, with the pay gap being wider among disabled women and non-disabled men. Median hourly pay for disabled women (£11.33) is £3.93 less than it is for non-disabled men (£15.25).

It’s not just pay. Women, Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers, and disabled workers all face other forms of inequality in the labour market. The unemployment rate is twice as high among BME workers as it is among white workers (6.9 per cent, compared to 3.2 per cent), and is higher still among BME women (8.1 per cent) 32

. BME workers are also more likely to be in insecure work 33

, and a recent TUC report found that two in five BME workers reported experiencing racism at work in the last five years 34

.

Disabled people face a higher unemployment rate and a lower employment rate than non-disabled people. The employment gap is 28.5 percentage points, and the unemployment rate for disabled workers is double what it is for non-disabled workers (6.8 per cent compared to 3.4 per cent) 35

. Labour market inequalities for BME and disabled workers combine. Disabled BME workers face an unemployment rate almost four times higher than the unemployment rate for non-disabled white workers (10.9 per cent compared to 2.8 per cent). The rate is highest among disabled BME women (11.3 per cent).

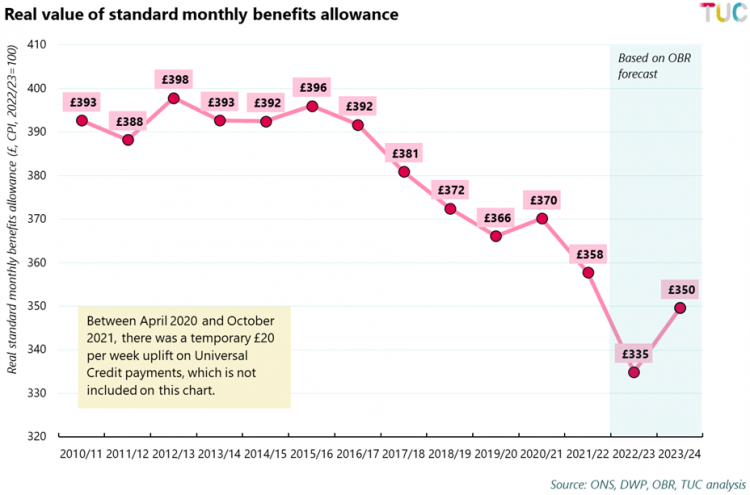

And while more workers face insecurity at work, government have also dramatically weakened the safety net. Cuts in social security since 2010 have left millions in poverty. The current levels of benefits are simply not enough to live on, and the rising cost of living is it making it even harder to survive on them. The standard benefit payment for over 25s without housing costs is £77 a week.

Since 2010/11, the real value of the standard benefits payment has dropped by £58 per month. Even with the uprating in line with September 2022 inflation set to come into effect this April, the real value of the standard payment will still be £43 per month lower than it was in 2010.

- 28 https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-why-employment-rights-need-overhaul

- 29 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1112717/transport-strikes-minimum-service-levels-bill-impact-assessment.pdf

- 30 Gender pay gap in the UK: 2022, ONS (2022). Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2022

- 31 Jobs and pay monitor - disabled workers, TUC (2022). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-pay-monitor-disabled-workers

- 32 A09: Labour market status by ethnic group, ONS. Figures used are from Jul-Sep 2022. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/labourmarketstatusbyethnicgroupa09

- 33 Insecure work – Why employment rights need an overhaul, TUC (2022). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-why-employment-rights-need-overhaul

- 34 Still rigged: racism in the UK labour market, TUC (2022). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/still-rigged-racism-uk-labour-market

- 35 Jobs and pay monitor - disabled workers, TUC (2022). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-pay-monitor-disabled-workers

Trussell Trust data for April to September 2022 shows they distributed 1.3 million food parcels to people facing hardship – this is an increase of 52% compared to the same period in 2019. Half a million of these parcels were distributed to children.36

New research by Joseph Rowntree highlights 7.2 million households are going without the basics, and this takes in to account the May 2022 energy support package provided. 37

Rising food costs and bills mean that much of the support – delivered through the emergency budget in May was used up on food: the Trussell Trust reported almost two-thirds (64%) of Universal Credit claimants had to spend July’s first Cost of Living Payment from the government on food. 38

No additional financial support has been given to children in the current cost of living crisis and yet nearly one in three children in the UK live in poverty. Analysis by the TUC, IPPR and CPAG shows increasing child benefit by £20 per week per child would reduce child poverty by 500,000, lifting a total of 700,000 people overall from poverty, at a cost of £9.9 billion. 39

Rather than temporary support schemes the Government needs to put in place permanent improvements to the levels of social security.

- 36 Almost 1.3 million emergency parcels provided in last 6 months - The Trussell Truste

- 37 Going under and without: JRF’s cost of living tracker, winter 2022/23 | JRF

- 38 Forty percent of people claiming Universal Credit skipping meals to survive, new research from the Trussell Trust reveals - The Trussell Trust

- 39 A lifeline for families: Investing to reduce child poverty this winter | IPPR

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox