Insecure work - Why employment rights need an overhaul

Government inaction has left 3.7 million people in insecure work.

Despite the Government’s promise to make Britain the best place in the world to work, huge numbers of workers don’t know when their next shift will be or if they will be able to pay their bills.

It is notable that five years after the report of the Taylor Review of modern working practices that most of its flagship measures remain unimplemented. And the employment bill ministers repeatedly committed to appears to have been shelved.

Instead, the government has sought to attack trade union rights by imposing a levy on unions, making it easier for agency workers to be brought in for striking workers and upping the damages employers can claim for industrial action.

We need a new approach that restores power to workers to negotiate better rights.

Introduction: the impact of insecure work

The TUC brings together more than 5.5 million working people who belong to our 48 member unions. We support trade unions to grow and thrive, and we stand up for everyone who works for a living. Every day, we campaign for more and better jobs, and a more equal, more prosperous country.

Trade unions have led the fight against insecure work but in the face of government inaction the numbers experiencing it remain stubbornly high.

TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey data shows that 3.7 million people are in insecure work.[1] This amounts to around one in nine of the workforce.

When estimating the number of people in insecure work the TUC includes:

- those on zero-hours contracts

- agency, casual and seasonal workers (but not those on fixed – term contracts)

- the low-paid self-employed who miss out on key rights and protections that come with being an employee and cannot afford to provide a safety net for when they are unable to work.

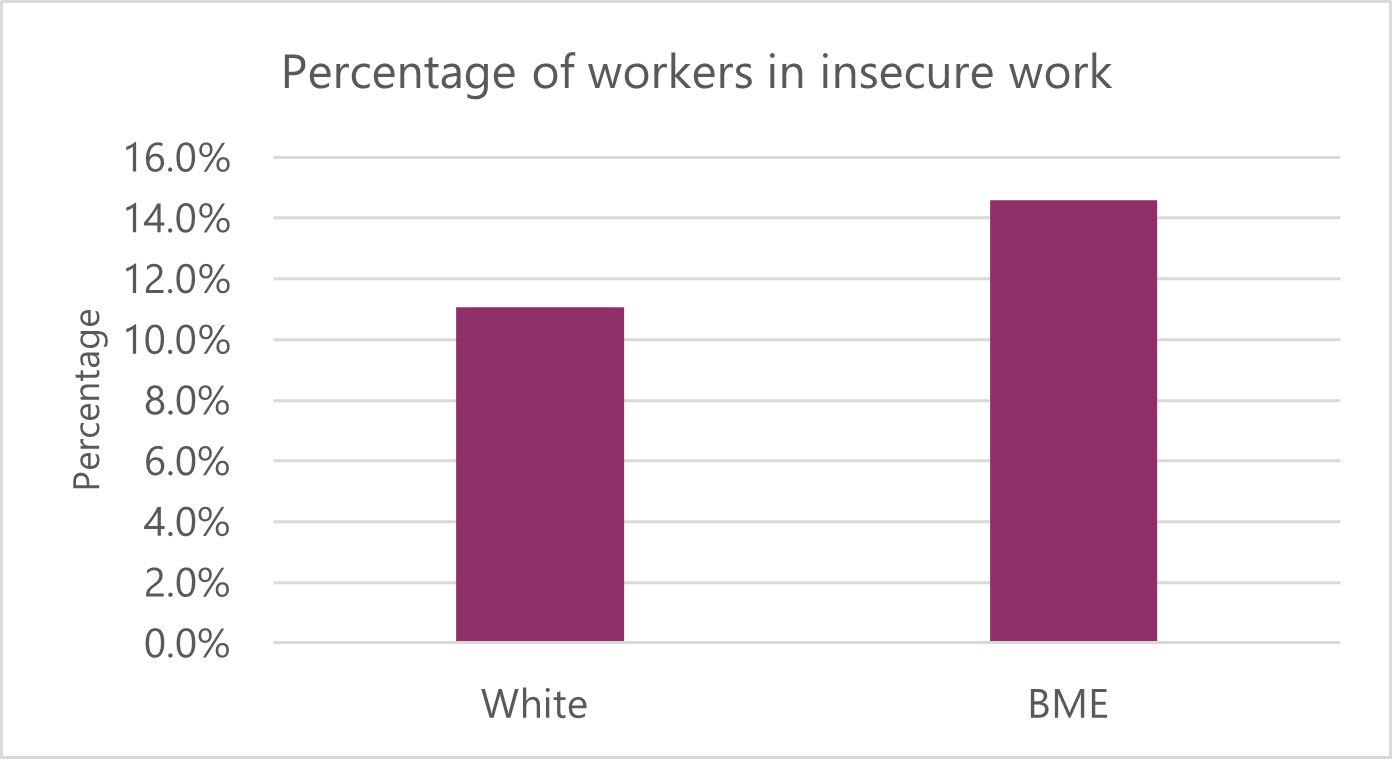

Insecure work also highlights prevailing structural inequalities. Our research shows that one in six (14.6 per cent) of Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers is likely to be in insecure work. This compares to 11.1 per cent of white workers in this position.

The extent of insecure work surged after the financial crisis that hit in 2007. As much as two-thirds of the employment growth in the UK after 2008 was accounted for by zero hours contracts, agency work, temporary work and low-paid self-employment.[2] Our research shows that millions remain in its clutches.

This matters because insecure work has an enormous effect on workers. The prospect of having work offered or cancelled at short notice makes it hard to budget household bills or plan a private life.

It also further distorts power in the workplace. If you are reliant on the whims of a boss for your next shift you are far less likely to complain about conditions, let alone ask for a pay rise.

Previous polling for the TUC has shown that employers are increasingly willing to offer shifts at short notice to workers on zero-hours contracts. In 2021, research for the TUC found that:

- 84 per cent of these workers have been offered shifts at less than 24 hours notice; and

- more than two-thirds of zero hours contracts workers (69 per cent) had had work cancelled at less than 24 hours notice.

- most zero hours workers only took on this type of contract because it was the only work available.[3]

Successive Conservative governments have failed to honour promises to improve conditions in insecure occupations which have blighted the labour market, especially since the great financial crisis that began 15 years ago:

- The government commissioned the Taylor Review on modern working practices which reported in 2017 – but has failed to implement most of its recommendations.

- On dozens of occasions ministers promised an employment bill to help those on zero hours contracts and who can’t access flexible work but with no action in the 2022 Queen’s Speech, now appear to have abandoned this commitment.

With the economic outlook seeming gloomy, there is a strong risk that, without action, there could be a repeat of past recessions where those in insecure work bear the brunt of job losses and worsening pay.

Unions have led the fight for better conditions for insecure workers. Unions have secured collective agreements at platform operators, such as Uber and Deliveroo, to raise the floor of conditions. And they have fought to bring back in-house public contracts that rely on insecure contracts.

For their part, instead of focusing on tackling insecure work, ministers have launched a succession of attacks on trade unions. This has included imposing an annual levy on trade unions, introducing measures that will enable strikers to be replaced by agency workers and upping the damages employers can claim if unions inadvertently breach complex rules on industrial action.

There needs to be a rebalancing of rights in the workplace so that those in insecure work can secure the decent pay and conditions that they need. As a start this should include:

- Ending the abusive use of zero-hours contracts

- Allowing unions access to workplaces to discuss the benefits of joining a union, mirroring practice in New Zealand.

- Introducing fair pay agreements to raise the floor of pay and conditions in sectors with insecure work.

The extent of insecure work

Who is in insecure work?

TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey data shows that 3.7 million people are in insecure work. This amounts to around one in nine of the workforce.

|

Who is in insecure work? |

|

|

Zero-hours contract workers (excluding the self-employed and those falling in the categories below) |

935,000 |

|

Other insecure work - including agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed-term contracts |

952,000 |

|

Low-paid self-employed (earning an hourly rate less than the minimum wage) |

1.9m |

|

TUC estimate of insecure work |

3.7m |

|

Proportion in insecure work |

11.5% |

Source: Labour Force Survey 2021 Q4 and Family Resources Survey 2020/1

Occupation

Analysis previously undertaken by the TUC shows that insecure work is not limited to those in gig economy roles in areas such as food delivery that have emerged in recent years. Previous TUC work has shown that 14.7 per cent of working people in England and Wales, equivalent to approximately 4.4 million people, now undertakes platform work at least once a week.[4]

Nevertheless insecure work is widespread many traditional roles.

Due to issues with the data in the family resources survey we were not able to produce analysis of the insecure work data breaking it down by occupation and region this year. However, we have data from the previous year.

Our 2021 analysis showed that nearly one in four (23.1 per cent) of those in elementary occupations including security guards, taxi drivers and shop assistants are in insecure work. It is the same for more than one in five (21.1 per cent) of those who are process, plant and machine operatives. Very large numbers of those in the skilled trades and caring, leisure and other service roles are also in precarious employment. This compares to just one in 20 (5 per cent) of those in professional occupations and a similar proportion (5 per cent) of those who undertake administrative and secretarial work.

|

Proportion in insecure work – by occupation |

|

|

Managers, Directors and Senior Officials |

8.2% |

|

Professional |

5.0% |

|

Associate Professional and Technical |

8.7% |

|

Administrative And Secretarial |

5.0% |

|

Skilled Trades |

19.7% |

|

Caring, Leisure and Other Service |

18.7% |

|

Sales And Customer Services |

8.0% |

|

Process, Plant and Machine Operatives |

21.1% |

|

Elementary |

23.1% |

Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey 2020 Q4 and Family Resources Survey 2019/20

Region

Likewise, in every region of England and in Wales and Scotland a significant number of workers are in insecure work.

Our analysis published in 2021 shows that it is particularly prevalent in Wales (13.4 per cent) and in Northern Ireland (12.2 per cent).

In only two areas, Yorkshire and Humberside (9 per cent) and Scotland (9.8 per cent), are fewer than one in ten workers recorded as being in insecure work.[5]

|

Proportion in insecure work – by Region |

|

|

North East |

10.7% |

|

North West |

10.9% |

|

Yorkshire and Humberside |

9.0% |

|

East Midlands |

10.3% |

|

West Midlands |

11.0% |

|

East of England |

13.7% |

|

London |

11.0% |

|

South East |

10.7% |

|

South West |

12.4% |

|

Wales |

13.4% |

|

Scotland |

9.8% |

|

Northern Ireland |

12.2% |

Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey 2020 Q4 and Family Resources Survey 2019/20

Gender

Patterns of insecurity vary significantly between men and women.

Overall, there are two million men in insecure work, more than the 1.7 million women in the same position. This equates to 12.1 per cent of male workers and 10.9 per cent of female workers being in insecure work.

When it comes to employees (so excluding the self-employed), women are more likely to be in insecure arrangements. Some 7.5 per cent of female employees are in insecure work, as opposed to 5.9 per cent of male employees.

However, men are significantly more likely to be in low-paid self-employment. There are 1.2 million men earning less than the minimum wage for their age group compared to 640,000 women.

|

Insecure work by gender |

||||

|

|

Number |

Proportion |

||

|

|

Male |

Female |

Male |

Female |

|

Total insecure employees |

837,000 |

1,050,000 |

5.9% |

7.5% |

|

Total in insecure work |

2,057,000 |

1,690,000 |

12.1% |

10.9% |

Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey 2021 Q4 and Family Resources Survey 2020/21

Ethnicity

TUC analysis of official data shows that BME workers are far more likely than white workers to be in insecure work.

Our analysis found that one in six (14.6 per cent) BME workers is in insecure work. This is far ahead of the 11.1 per cent of white workers in the same position.

Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey 2021 Q4 and Family Resources Survey 2020/21

Black women have long been particularly badly served by the labour market.

Our research shows when looking at employees alone, BME women are more than twice as likely as white men to experience insecure arrangements. One in 9 BME women are insecure employees compared to one in 19 white men.

|

Insecure employees as proportion of employment |

||

|

|

White |

BME |

|

Male |

5.4% |

9.3% |

|

Female |

6.9% |

11.6% |

Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey 2021 Q4

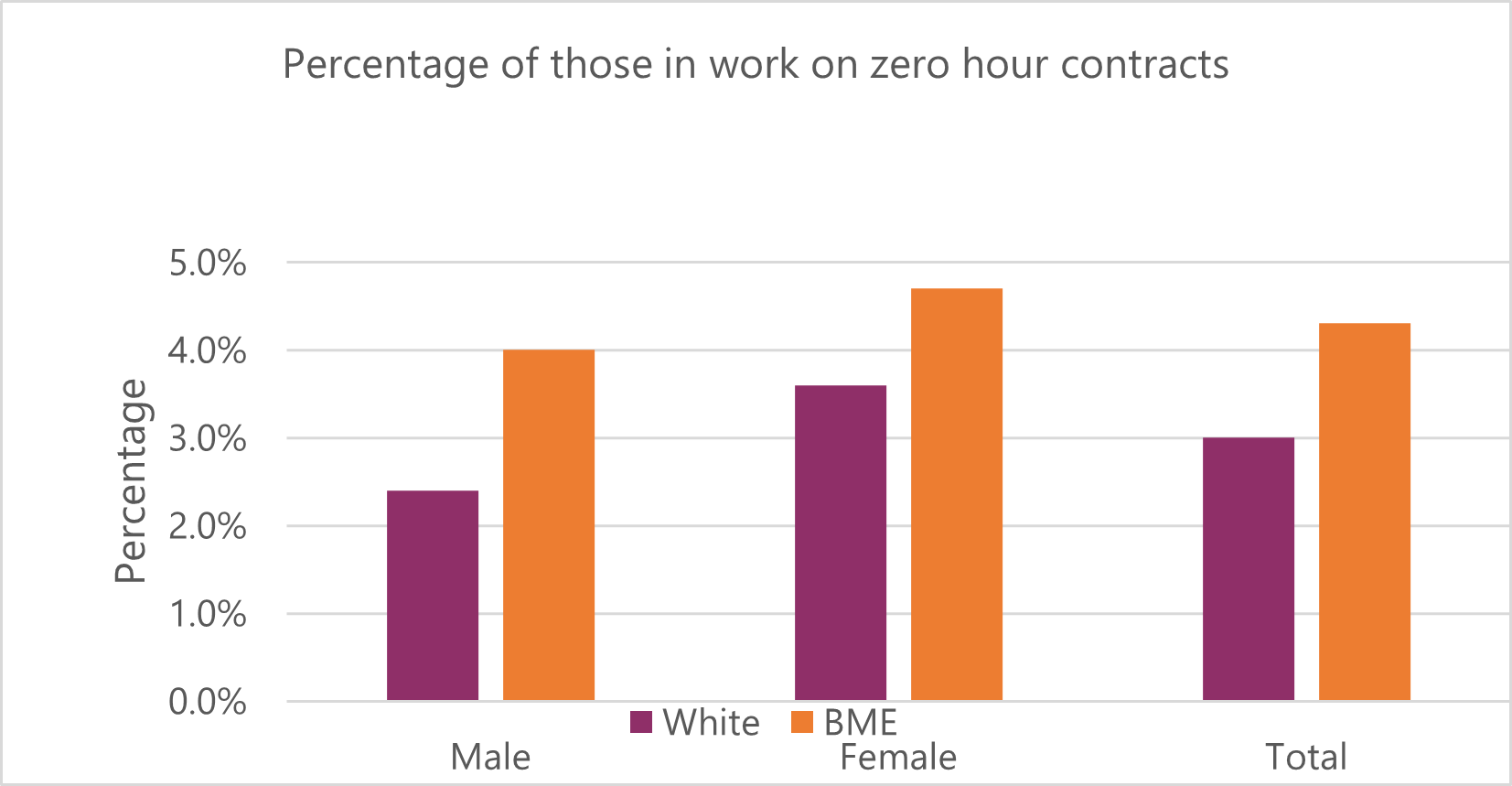

This picture is replicated in among those on zero-hours contracts.

Our analysis also shows that 2.4 per cent of white men are on zero-hours contracts. This is barely half of the 4.7 per cent of BME women who experience these precarious arrangements.

One piece of analysis we are unable to do this year is assess the overall level of insecure work by gender and ethnicity. Covid restrictions limited the collection of official data during the pandemic making sample sizes for those in low-paid self-employed work too small for robust analysis of this aspect.[6]

Conclusion and recommendations

The publication of the Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices five years ago could have provided the basis for useful reforms to improve the lives for those in insecure work.

Instead it has been added to the list of missed opportunities that have left workers poorer and less secure.

As our analysis shows, insecure work remains stubbornly high, afflicting the lives of millions of workers and their families.

Throughout the last 15 years, unions have fought hard for workers at the sharp end of the labour market.

But ministers have done their utmost to hobble their efforts. Even in recent weeks as the living standards crisis has spiralled ministers have introduced more anti-union measures designed to hamper their ability to fight for their measures.

To ensure that every worker has a decent job, government should:

Strengthen collective bargaining

- Unions should have access to workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership and collective bargaining (following the system in place in New Zealand).

- The government should establish new fair pay agreements, where unions and employers negotiate across sectors to set minimum standards, starting with hospitality and social care. New Zealand is currently legislating to introduce this system, widespread across Europe, into its labour market.[7]

- We need new rights to make it easier for working people to negotiate collectively with their employer, including simplifying the process that workers must follow to have their union recognised by their employer for collective bargaining and enabling unions to scale up bargaining rights in large, multi-site organisations.

- The scope of collective bargaining rights should be expanded to include all pay and conditions, including pay and pensions, working time and holidays, equality issues (including maternity and paternity rights), health and safety, grievance and disciplinary processes, training and development, work organisation, including the introduction of new technologies, and the nature and level of staffing.

- Government must also repeal the Trade Union Act 2016, which frustrates workers’ efforts to defend their jobs, pay and conditions, and should not proceed with regulations designed to allow agency workers to strike break.

Upgrade rights and protections

In addition to new collective rights to enable workers to deliver decent work through their trade unions, we need a significantly strengthened set of employment protections. These must include:

- a ban on zero hours contracts through a right to a normal-hours contract and robust rules governing adequate notice of shifts and compensation for cancelled shifts

- an entitlement for all workers, including agency workers, zero-hours contract workers and casual workers, to the same floor of rights currently enjoyed by employees; these rights should be available from day one to all workers.

- a statutory presumption that all individuals will qualify for employment rights unless the employer can demonstrate they are genuinely self-employed

- penalties for employers who mislead staff about their employment status

- A ban on Umbrella companies

- Stronger collective consultation rights, including extending these to workers as well as employees and significantly stronger protection against unfair dismissal to protect against fire and rehire[8]

- Stronger flexible working rights, as set out in the section above on long-covid.

- The introduction of mandatory requirements to report on the pay gaps for Black, disabled and LGBT+ workers.

- Maintain the government’s commitments to a level playing field with European countries enshrined in the Trade and Co-operation Agreement.

Increase enforcement

For rights to be effective, they require enforcement. To tackle the challenges faced by workers the enforcement system needs further long-term resources, to end the counterproductive relationship with immigration enforcement which scares workers from reporting exploitation, and to make use of more innovative methods of enforcement, which are becoming common in other countries.

Government should:

- address the inadequate funding of the state-led enforcement system. The system needs further long-term resources, more inspectors, more proactive investigations and more enforcement actions. We fall well short of the benchmark established by the International Labour Organisation. To hit the ILO benchmark of one inspector per 10,000 workers, the UK would need 3,287 inspectors. There are currently 1,490. Another 1,797 labour market inspectors need to be recruited.

- Sever the ties between immigration enforcement and employment rights enforcement. Currently, there are close working relationships between employment rights enforcement agencies and immigration enforcement. Intelligence sharing and joint investigations are commonplace. Joint working should cease and a firewall between immigration enforcement and employment rights enforcement agencies should be established.

- Traditional employment relationships have become increasingly fragmented, with business strategies, such as franchising, outsourcing, lengthy supply chains and the use of labour market intermediaries enabling organisations to shirk their employment rights obligations. Large contractors should be liable for breaches of core employment rights in their supply chains.[9]

[1] The total number in ‘insecure work’ includes (1) agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed – term contracts, (2) workers whose primary job is a zero-hours contract, (3) self-employed workers who are paid less than the National Living Wage (£9.50).

Data on temporary workers and zero-hour workers is taken from the Labour Force Survey (Q4 2021). Double counting has been excluded. The minimum wage for adults over 23 is currently £8.91 and is also known as the National Living Wage. The number of self- employed working people aged 23 and over earning below £9.50 is 1,860,000 from a total of 3,430,000 self-employed workers in the UK. The methodology is slightly different to last year as previous analysis looked at self-employed aged over 25, and the age threshold has now changed to 23. The figures come from analysis of data for 2020/21 (the most recent available) in the Family Resources Survey and were commissioned by the TUC from Landman Economics. The Family Resources Survey suggests that fewer people are self-employed than other data sources, including the Labour Force Survey.

[2] Clarke, S (2019). Setting the record straight, Resolution Foundation

[3] TUC (2021). Jobs and recovery monitor - Insecure work, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-monitor-inse…

[4] TUC (2021). Seven ways platform workers are fighting back, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/seven-ways-platform-workers-ar…

[5] TUC (2021). Jobs and recovery monitor - Insecure work, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-monitor-inse…

[6] The low paid self-employed data is from the Family Resources survey 2020/21. This publication is the first survey year where coronavirus (COVID-19) has impacted data collection. In March 2020, the introduction of Government restrictions led to a compulsory halt to face-to-face interviewing in the home to phone interviews. This shift in mode of interview has been accompanied by a substantial reduction in the number of interviews achieved. More detailed data available in previous years is not available this year.

[7] See https://www.mbie.govt.nz/business-and-employment/employment-and-skills/employment-legislation-reviews/fair-pay-agreements/

[8] Further details are set out here: https://www.tuc.org.uk/blogs/po-private-schools-protect-workers-hire-and-fire-culture

[9] See TUC (2017) Shifting the risk: Countering business strategies that reduce their responsibility to workers - improving enforcement of employment rights at https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Shiftingtherisk.pdf

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox