Levelling up at work - fixing work to level up across the UK

“Levelling up” is a worthwhile and justifiably popular aim. Who can disagree with the idea of bringing up poorer communities to the level of wealthier ones? The government has made “levelling up” a central aim - but slogans don’t always translate neatly into policy. We need an open and transparent debate about what levelling up means in practice, how success in levelling up will be measured and how we can make it happen.

This report aims to make a contribution to this debate by focussing on the centrality of work to the levelling up agenda. It argues that poor quality work is a key cause of broader inequality across the country and within all regions and nations, including those seen as the target for levelling up. While other strategies - including infrastructure projects, transport improvements and community wealth-building - have an important role to play, unless we reduce the numbers of people in jobs that are in low-paid, insecure and offer no route to better quality work, little will change in the lived experience of a significant number and proportion of people across every part of the UK. We cannot level up the country without levelling up at work. Ensuring access to decent, secure work for everyone is a key test of the levelling up agenda.

Work has a significant impact on the quality of our lives.

For most of us, work is our main source of income through most of our lives and therefore a key determinant of whether we are comfortably off or struggling to put food on the table. And for too many working people, the link between work, security and opportunity is broken. Over half of those living in poverty are in working households – and this rises to a shocking three quarters of children living in poverty. Too many people find their work is trapping them in poverty, rather than providing a route out. And this is a national, rather than a regional problem, as shown by the table below:

Rates of in-work poverty by region and nation (data is a 3-year average)

|

|

2017/18 - 2019/20 |

|

North of England |

17.7% |

|

South of England and East |

15.2% |

|

London |

21.8% |

|

Midlands |

17.6% |

|

Wales |

17.6% |

|

Scotland |

13.7% |

IPPR Analysis of DWP (2020a) Households Below Average Income (HBAI) 2017/18 – 2019/20 (data refers to the number of people in working families who are in relative household poverty)

The quality of our work – in particular, the control or lack thereof we have over our working lives – has a major impact on our health. The government is right to highlight tackling postcode disparities in health as an important aim of levelling up, but these in part reflect the stark occupational differences in health outcomes. One in three low-paid workers who left their jobs before state pension age did so because of ill health. By contrast, just one in twenty professionals who left the labour market early did so because of long-term sickness. If we leave millions of people in low-paid insecure work, significant economic and social disparities in health outcomes and life expectancy will remain.

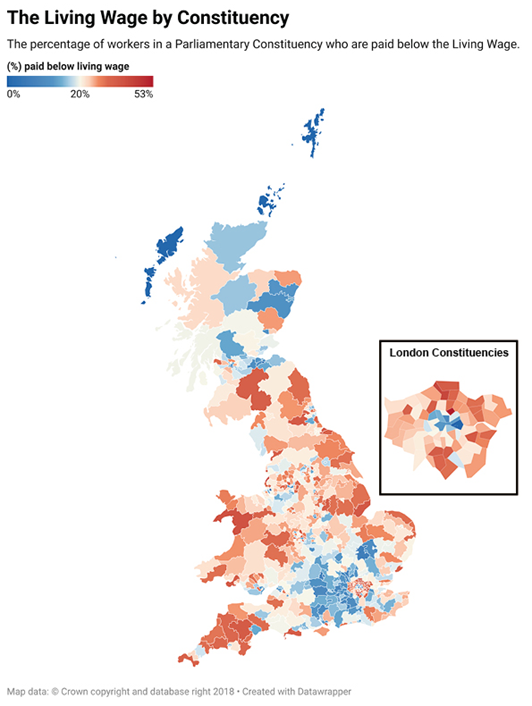

Low-pay and insecurity are not neatly concentrated by geography – rather, they are prevalent across every region and nation. Over one in seven jobs in every region and nation is paid less than the Real Living Wage. In over 62% of constituencies, more than one in five jobs are paid below the Real Living Wage. Across the North East, West Midlands and Wales the share is more than three quarters, in London it is 84% and in Yorkshire and the Humber every constituency has high rates of low pay. The lowest rates of low pay are in the South East and then Scotland, but even here 16 percent and 17 percent respectively of employees are paid less than the Real Living Wage.

This reflects the fact that low paying sectors are large employers across all regions and nations, with retail and social care among the top sectors of employment in every region and nation. Strategies which ignore these sectors cannot deliver levelling up.

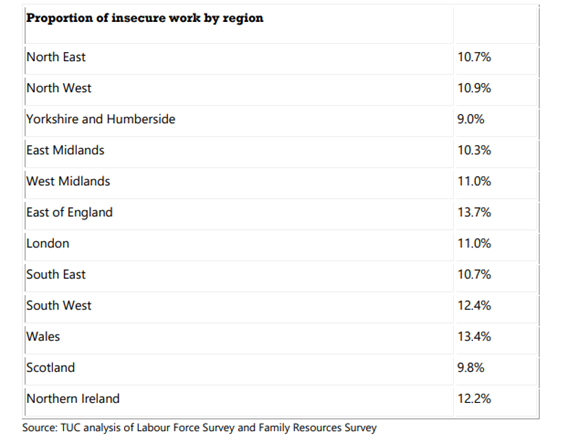

Like low pay, insecure work is endemic across every region and nation of the UK. Only Yorkshire and Humber and Scotland have less than one in ten workers in insecure work.

The distribution of insecure work and low pay both reflects and deepens existing inequalities. Black and minority ethnic workers are more likely to be in insecure work than white workers, while women are more likely to be low paid than men. Disabled workers face significant employment and pay gaps compared with non-disabled workers. These differences reflect and but also reinforce discrimination, creating further barriers to change.

We need to address the challenge of poor-quality work head on. Much industrial and regional policy has aimed to redistribute better paid jobs more evenly across the country. Achieving a better distribution of high-skilled, high-paid jobs around the country is an important part of what is needed to level up. However, if it is not linked to strategies to improve the experience and rewards of low-quality work, poverty and insecurity will remain endemic across the country. As well as creating new good quality jobs, we need to level up the jobs that people are already in.

The experience of London shows that the creation and existence of high-paid jobs in an area and does not automatically lead to rising incomes and quality of life for the wider community. Indeed, unless low-pay and poverty are also addressed, there is a danger that the creation of high-paid jobs will lead to deepening inequality, unaffordable housing and being priced out of local amenities for many local people. As the table above showed, London has the highest rate of in-work poverty in the country, with 21.8 per cent of people in poverty in a working household. The creation of good quality, green jobs is desperately needed – but it’s not enough on its own.

If we are to level up the country, we need to level up at work. This report sets out a plan for how to make it happen.

Recommendations

Creating an economy based on decent work

We need to change the way our economy works so that economic growth translates into good quality jobs. This requires an institutional environment that encourages the development of business models based on high-wage, high-skilled and secure jobs, rather than a reliance on low-paid and insecure work. Without reforms that hard wire decent work into business models, strategies to boost research and development, or to attract new investment, while welcome, will not deliver the good jobs people need.

To change the economic incentives that shape our economy, we need a new skills strategy, reform of corporate governance and industrial policies, and new measures to strengthen workforce voice and collective bargaining to give working people more power in the workplace.

A new lifelong learning and skills strategy for all workers

The TUC is calling for a new national lifelong learning and skills strategy based on a vision of a high-skill economy, where workers can quickly gain both transferable and specialist skills to build their job prospects. Delivering this would require:

- A significant boost to investment in learning and skills by both the state and employers. People should have access to fully-funded learning and skills entitlements and new workplace training rights throughout their lives, expanding opportunities for upskilling and retraining.

- These entitlements should be incorporated into lifelong learning accounts and accompanied by new workplace rights, including a new right to paid time off for learning and training for all workers.

Corporate governance reform to promote long-term, sustainable growth

Shareholder primacy in corporate governance encourages directors to prioritise shareholder returns over wages and long-term investment, fuelling short-termism and poor employment practices. We need to address shareholder primacy through reform of directors’ duties and promoting workforce voice in corporate governance.

The inclusion of worker directors on company boards would bring people with a very different range of experiences into the boardroom, which would help to challenge ‘groupthink’ and change the culture and priorities of the boardroom, improving the quality of board decision-making.

- Directors’ duties should be reformed so that directors are required to promote the long-term success of the company as their primary aim, taking account of the interests of stakeholders including the workforce, shareholders, local communities and suppliers and the impact of the company’s operations on human rights and on the environment.

- Company law should require that elected worker directors comprise one third of the board at all companies with 250 or more staff.

Strengthening workforce voice and collective bargaining

Giving workers stronger rights to organise collectively in unions is key both to raising pay and working conditions and giving workers more say over their working lives. Collective bargaining promotes higher pay, better training, safer and more flexible workplaces and greater equality. The absence of a collective approach to driving up employment standards has led to the poor pay and conditions that are now resulting in labour shortages across the country.

- We need to give workers stronger rights to speak with one voice and bargain with their employer and give unions access to workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership, following the New Zealand model.

- And starting in sectors that are characterised by low pay and poor conditions, we need to create new bodies for workers and employers to come together to set minimum standards and Fair Pay Agreements across the sector, starting with social care.

Industrial and trade policies to promote good jobs

To boost domestic manufacturing, services and technology development, and reap the full benefit of developments in infrastructure and renewable energy, the government should adopt strong trade and procurement policies to strengthen local supply chains and raise employment standards.

- The UK government should use local content requirements where they are legal and needed.

- Trade deals and WTO rules should be used as a lever to lock in the highest standards by enforcing respect for International Labour Organisation (ILO) standards. Too often, rights have been defined disparagingly in trade deals as ‘non-tariff barriers’ that should be removed.

Government leading by example – public services, job creation and procurement

The government should lead by example by showcasing good quality employment practices as an employer and making decent jobs a requirement of all government spending so that the power of government spending is used to drive up employment standards.

Strong and resilient public services are vital for levelling up

The experience of the pandemic has shown us how much we rely on and value public services and the public servants who deliver them. Strong public services are a vital part of any effort to end inequality, a source of good quality employment and key to building resilient communities able to grow and thrive.

To truly level up, the government must undo the damage inflicted by cuts on public services over the last decade. Public sector workers are one in seven employees in every region in the UK, and in the North East, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland they are over one in five. We need a long-term plan backed up by sustainable and substantial investment, and delivered by workers who are properly rewarded and employed directly by the public sector.

- Government must end the cuts to public services and invest to reverse them, bringing investment back to the levels we need to maintain quality and meet demand.

- We cannot level up while holding down public sector pay. The public sector pay freeze should be ended and workers paid at least the real living wage. Pay rises must keep pace with the increased cost of living, while making up for lost earnings over the last decade.

- Public ownership and in-house provision must be the default for setting public services, unless there a strong public interest case for putting services out to tender.

Procurement and investment standards to support decent work

Decisions on infrastructure spending, including through the National Infrastructure Strategy, should be subject to a job creation and quality test that evaluates both the quantity of jobs created by a proposed development and their quality, according to an agreed set of measures.

The government should:

- Build job creation and job quality tests into public investment decision-making and procurement standards

- Use Olympics style agreements to guarantee decent jobs in big infrastructure projects.

Strengthening the floor of employment protection for all workers

We need to reform the way the economy works so that economic growth translates into decent work that will level up people’s lives and the communities where they live. But tackling low pay and insecurity also requires strengthening the floor of employment protection for all workers to make the worst forms of exploitation illegal, raise the wages of the lowest paid and tackle structural discrimination at work.

We need to ban zero hours contracts by giving workers the right to a contract that reflects their normal hours of work, coupled with robust rules on notice of shifts and compensation for cancelled shifts.

- The minimum wage should be raised to at least £10 an hour immediately to put more money into workers’ pockets and address in-work poverty.

- The government should strengthen the gender pay gap reporting requirements, and introduce ethnic and disability pay gap reporting, requiring employers to publish actions plans on what they are doing to close the pay gaps they have reported.

- The government must comply with its existing public sector equality duty and proactively consider equality impacts at each stage of any policy-making process, with a view to promoting equality and eliminating discrimination.

Beyond the workplace – strengthening our safety net

For most people, work is their main source of income throughout their lives. But for all of us, there will be times that we are unable to work. These include periods of old age, ill-health or when we are unable to find suitable work. And, of course, it includes time spent on the all-important role of bringing up the next generation, who need and deserve the very best start in life their families can give them.

People need economic security throughout every part of their lives. That’s why levelling up requires a strong safety net that supports people when they need it. We need a decent pension system, sick pay for all and a social security system that enables people to live in dignity.

- Because of the stark occupational differences in life expectancy, an ever-increasing state pension age will mean that people in poorer areas and in manual and low paid jobs are increasingly unlikely to be able to stay in work until they can start drawing their state pension. The government should shelve scheduled increases to the state pension age and maintain the pensions triple lock.

- The cut in Universal Credit must be reversed, and Universal Credit should be increased to at least 80 per cent of the level of the living wage, around £260 a week.

“Levelling up” is a worthwhile and justifiably popular aim. Who can disagree with the idea of bringing up poorer communities to the level of wealthier ones? The government has made “levelling up” a central aim – but while the term is easy to understand, it in itself implies nothing about how it will be achieved. This underlines the importance of an open and transparent discussion about what levelling up means in practice, how success in levelling up will be measured and how it can most effectively be brought about.

The levelling up agenda has been framed by the government as being primarily about addressing regional or geographical inequality. The 2019 Conservative Manifesto[1] talked about “levelling up all parts of the United Kingdom”, linking this to investments in infrastructure, a new deal for towns, transport, skills, supporting rural and coastal communities and freeports. With the exception of skills policy, this linked levelling up to regional or place-based initiatives.

Boris Johnson’s July speech[2] on levelling up again framed the problem in terms of geographical imbalances – decrying differences between different areas in life expectancy and healthy life expectancy, children on free school meals who go on to attend university and income per head. However, in discussing how these inequalities should be tackled, the speech pointed to national strategies, as well as regional or place-based one. Alongside improving transport and infrastructure and boosting local decision-making across counties and cities, the speech rightly cited the need for improved public services, boosting skills and training and “help[ing people] into good jobs on decent pay” as being part of what is needed to level up.

This report aims to make a contribution to this debate by focussing on the centrality of work to the levelling up agenda. It argues that poor quality work is a key cause of broader inequality across the country and within all regions and nations, including those seen as the target for levelling up. While other strategies - including infrastructure projects, transport improvements and community wealth-building - have an important role to play, unless we reduce the numbers of people in jobs that are in low-paid, insecure and offer no route to better quality work, little will change in the lived experience of a significant number and proportion of people across every part of the UK. We cannot level up the country without levelling up at work.

[1] Our Plan Conservative Manifesto 2019 https://www.conservatives.com/our-plan

[2] The Prime Minister's Levelling Up speech: 15 July 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-prime-ministers-levelling-up-speech-15-july-2021

Why does work matter? The impact of work on quality of life

The quality and quantity of work that people undertake has a huge impact on their wellbeing. Most obviously, it is a crucial determinator of income and how well-off people are – whether they struggle to buy food for their family or are able to budget comfortably for daily life, leisure and holidays and save for the future. But work also has a significant impact on other critical areas of people’s lives, in particular their health.

The strong link between work and health outcomes was underlined by the Marmot Review of 2010[1], which was set up under the leadership of Sir Michael Marmot to examine “the most effective evidence-based strategies for reducing health inequalities”. One of its six recommendations was to “create fair employment and good work for all”.

The Marmot review recognised that being in good employment is generally good for health, while unemployment, especially if it is long-term, contributes significantly to poor health. However, it concluded that being in work is not automatically good for health and found that a poor quality or stressful job can be more damaging to health than unemployment. Therefore: “Getting people off benefits and into low paid, insecure and health-damaging work is not a desirable option”.

The Marmot review set out five characteristics of work that evidence shows are damaging to health:

· job insecurity and instability

· low levels of control (over how the job is done)

· high levels of demand at work, especially when combined with low levels of control

· lack of supervisor and peer support

· more intensive work and longer hours.

As the Review sets out, these work characteristics are linked to a range of mental and physical health impacts, including depression, cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease and musculoskeletal disorders and metabolic syndrome (a combination of risk factors for diabetes and heart disease). Research clearly shows that work quality is directly linked to health outcomes and poor work quality increases the risk of being in poor health.

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) has produced guidance to help employers reduce workplace stress, focusing on six areas of work design that “if not properly managed, are associated with poor health, lower productivity and increased accident and sickness absence rates”[2]. The six areas - demand, control, support, relationships, understanding of role and management of change – closely correlate with the work characteristics highlighted by the Marmot Review. Unfortunately, HSE annual statistics report an increase in both the proportion and number of workers suffering work-related stress has increased in recent years[3]. The HSE’s 2020 Annual Statistics (covering the period up to March 2020) reported that in 2019/20, 828,000 workers suffered from work-related stress, depression or anxiety, leading to 17.9 million lost working days.

Boris Johnson’s July speech quoted some of the appalling postcode health inequalities, citing the extra decade of average healthy life expectancy of a woman from York compared to Doncaster 30 miles away. But these postcode health inequalities also reflect differences in occupation, work quality and pay.

In a recent report[4], the TUC found that people who left the labour market early while working in low-income jobs - like cleaning, care and manual labour - were six times more likely to quit for medical reasons than those in higher-paid jobs.

One in three low-paid workers who left their jobs before state pension age did so because of ill health. By contrast, just one in twenty professionals who left the labour market early did so because of long-term sickness.

The link between work and income is clear – different jobs are paid different amounts and so pay differentials across the economy are a significant contributor to income differentials and inequality, in particular for the working age population.

A distinctive feature of the UK labour market is the fact that so many working people remain in poverty.

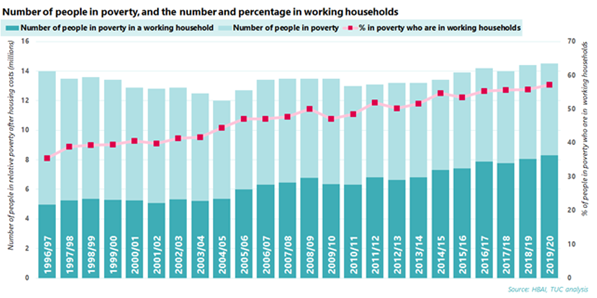

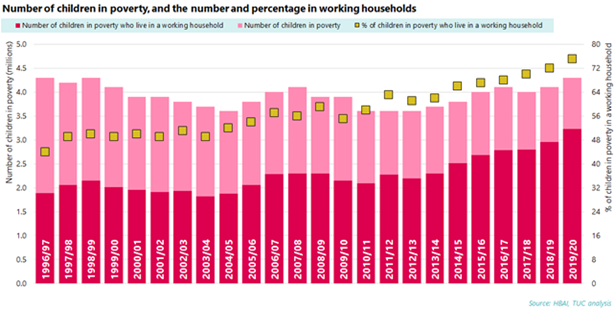

The most recent data, for 2019/20, shows the number of people living in poverty reaching 14.5 million, a record high. The number of children living in poverty reached 4.3 million, up 200,000 from the previous year. And of those living in poverty just before the pandemic hit, a record-high 57 per cent (8.3 million people) were in working households. And 75 per cent of children living in poverty are from working households. At the moment, the government’s mantra that work is the best route out of poverty, simply isn’t true. To ensure that work is the best route out of poverty, we need to improve work quality and pay – we need to level up at work.

The charts below shows that the number of people and children in poverty has risen over time and shows the number and proportion of people in poverty who are in a working household.

[1] Michael Marmot, Peter Goldblatt, Jessica Allen, et al. (2010) Fair Society Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review), available at https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review

[2] HSE Causes of stress at work https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/causes.htm

[3] Health and Safety Executive (4 November 2020) Work-related stress, anxiety or depression statistics in Great Britain, 2020 https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/causdis/stress.pdf Nb figures cover the period to March 2020 and the HSE does not consider COVID-19 to be the main driver of the increase.

[4] TUC (2021) Extending working lives How to support older workers, available at https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/extending-working-lives-how-support-older-workers

Timeline of number of people in poverty, with working household breakdown

Timeline of number of children in poverty, with working household breakdown

As the next section will show, the working poor are not found in some regions or towns only; they are found in every region, every town and every city across the UK. We cannot address disadvantage and level up the country without addressing the problems of poor-quality work and low pay. Without a chance of a decent secure job, no community will feel that their chances have been ‘levelled up’.

Low pay across the UK

Across the UK in 2019, one in five jobs (20.5%) or five million jobs in total was paid less than the Real Living Wage - currently set at £10.85 in London and £9.50 across the rest of the UK[1]. (In 2019, at the time of the analysis, the figures were £10.55 in London and £9.00 across the rest of the UK – we have used the 2019 figures as the 2020 figures were distorted by the number of employees on furlough).

While the share of low paid jobs is higher in some regions than in others, a significant proportion of workers are low paid in every region and nation of the UK. Across the UK as a whole, in 2019 in 62% of constituencies more than one in five jobs were paid below the Real Living Wage. Across the North East, West Midlands and Wales the share was more than three quarters, in London it was 84% and in Yorkshire and the Humber every constituency had high rates of low pay. The lowest rates of low pay were in the South East and then Scotland.

The table below shows the share of parliamentary constituencies in each region or nation of the UK with more than 20 per cent of employees paid below the Real Living Wage (labelled as constituencies with high levels of low pay).

As this data excludes the self-employed, it will significantly underestimate the total extent of low pay. TUC analysis in 2019 found that almost half of self-employed adults aged over 25 were earning less than the legal minimum wage[2]. Our current estimate of the total number of self-employed workers who are paid below the legal minimum wage is 1.91 million[3].

Low pay (pay below the Real Living Wage) across the regions and nations of the UK, 2019[4]

|

|

Percentage of employees on low pay |

Number of employees on low pay |

Constituencies with high levels (over 20%) of low pay |

|

|

Number |

Percentage |

|||

|

North East |

22.6 |

229,000 |

22 |

76 |

|

North West |

21.1 |

629,000 |

53 |

71 |

|

Yorkshire and the Humber |

22.1 |

492,000 |

57 |

100 |

|

East Midlands |

22.8 |

432,000 |

17 |

40 |

|

West Midlands |

21.7 |

488,000 |

46 |

78 |

|

East |

18.8 |

471,000 |

30 |

52 |

|

London |

19.8 |

839,000 |

61 |

84 |

|

South East |

15.9 |

610,000 |

21 |

25 |

|

South West |

20.4 |

482,000 |

29 |

53 |

|

Wales |

22.6 |

268,000 |

31 |

78 |

|

Scotland |

16.9 |

400,000 |

24 |

41 |

|

Northern Ireland |

25.1 |

227,000 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

UK |

20.5 |

5,568,000 |

391 |

62% |

[2] ONS, TUC analysis https://www.tuc.org.uk/blogs/almost-half-self-employed-are-poverty-pay

[3] see footnote 15 for source

[4] Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) - Estimates of the number and proportion of employee jobs with hourly pay below the living wage, by work geography, local authority and parliamentary constituency, UK, April 2018 and April 2019; constituency counts were derived by the TUC.

The heat map below presents a graphical version of the same information. It demonstrates that constituencies with high rates of low pay are relatively evenly distributed across the whole of the UK. The darkest red corresponds to shares around 50 per cent and the darkest blue to shares of less than 10%.

It is high pay, rather than low pay, that is unevenly distributed and tends to be focussed in a smaller number of areas. IFS analysis[1] shows the highest earning local authorities concentrated in London, and then the South East and East of England.

The prevalence of high-paid jobs in London means that comparisons between London and other regions can give rise to statistics that make it look as though the streets of London are paved with gold. But that is just a fairy story and the reality is much more complex – of the ten constituencies with the highest share of low paid workers, eight are in London and the list is topped by Hackney North and Stoke Newington, where over half (53%) of jobs are paid less than the Real Living Wage.

The story of London is that the prevalence of high paid jobs does not automatically pull up incomes for others in the local community. The prevalence of higher income work will create additional local economic demand, in particular in the service sector; but as long as so many service sector jobs remain low paid, this has the effect of expanding the low paid local economy, rather than fostering rising incomes across the board.

The prevalence of low paid work across all regions and nations means that in-work poverty is high across all regions and nations, as shown by the table below:

Rates of in-work poverty by region and nation[2] (data is a 3-year average)

|

|

2017/18 - 2019/20 |

|

North of England |

17.7% |

|

South of England and East |

15.2% |

|

London |

21.8% |

|

Midlands |

17.6% |

|

Wales |

17.6% |

|

Scotland |

13.7% |

Department for Work and Pensions [DWP] (2020a) ‘Households below average income (HBAI)’ dataset

Sectors and occupations

The reason that low pay is so common across all areas of the country is that many sectors and occupations that employ large numbers of people across the UK are poorly paid.

The table below looks at the top employing sectors in each of the UK’s regions and nations (with the top employing sector highlighted in darkest green, and the fifth largest employing sector in the lightest green).

Largest employing sectors in the UK, regions and nations (workforce jobs, June 2021)

|

Industry |

UK |

North East |

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

East Midlands |

West Midlands |

East |

London |

South East |

South West |

Wales |

Scotland |

Northern Ireland |

|

% of workforce jobs |

|||||||||||||

|

Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles |

13.9 |

13.9 |

14.7 |

13.9 |

14.9 |

15.7 |

14.6 |

10.6 |

15.0 |

14.2 |

13.8 |

13.0 |

15.2 |

|

Human health and social work activities |

12.9 |

15.9 |

13.9 |

14.1 |

12.2 |

13.0 |

12.3 |

10.6 |

12.1 |

12.7 |

14.9 |

14.6 |

16.5 |

|

Professional, scientific and technical activities |

9.2 |

6.4 |

9.9 |

7.0 |

8.3 |

7.9 |

10.0 |

13.4 |

9.6 |

8.1 |

5.4 |

8.1 |

5.3 |

|

Administrative and support service activities |

8.4 |

7.6 |

8.5 |

8.6 |

8.4 |

9.4 |

9.4 |

10.0 |

7.7 |

6.6 |

6.1 |

7.8 |

6.3 |

|

Education |

8.4 |

8.6 |

7.7 |

8.9 |

8.5 |

8.9 |

9.0 |

6.9 |

9.4 |

8.3 |

9.4 |

7.9 |

9.2 |

|

Manufacturing |

7.3 |

8.8 |

8.4 |

10.4 |

10.8 |

10.1 |

6.7 |

2.3 |

6.0 |

8.0 |

10.0 |

6.6 |

10.5 |

|

Accommodation and food service activities |

6.8 |

6.6 |

6.7 |

6.0 |

5.7 |

6.2 |

5.9 |

7.0 |

6.6 |

8.6 |

8.7 |

7.4 |

5.8 |

Source: Workforce jobs by industry, June 2021, accessed via nomis

Wholesale and retail and human health and social work activities dominate employment across the UK. Wholesale and retail is a low paid sector, with a median wage of £10.30 in 2020 (compared to a UK median of £13.68) and a significant 35 per cent of jobs paid below the real Living Wage in 2019.

Human health and social care incorporates a wide variety of jobs and has a higher median wage of £13.73 - but nearly one in five jobs, 18.1 per cent, were paid below the real Living Wage in 2019 – suggesting considerable potential for improving wages in this sector.

Accommodation and food services is the lowest paid sector in the UK, with a median wage of £8.72, and a shocking 63 per cent of employees paid below the real Living Wage. It’s notable that this is a top five employer in three parts of the country - London, the South West and Wales.[3]

The next table looks at the largest employing occupations across the regions and nations. Again, two low paid sectors, caring and elementary service occupations, make up a large share of jobs in most parts of the UK. Those working in elementary service occupations – for example in hospitality – make up a significant part of the workforce (over 7 per cent) everywhere except London, the South East and Northern Ireland – but 59 per cent of employees in these jobs were paid less than the real Living Wage in 2019, and the median wage was just £9.17 in 2020.

Caring and personal service jobs formed a similar proportion of the workforce (over 7 per cent) everywhere except London and the East; 35 per cent of them earned less than the Living Wage (with a median wage of £10.13). Sales occupations, which stand out as significant jobs in the North East and Northern Ireland (and make up around five per cent of employment in most regions except London) are paid a median of £9.30, and 59 per cent earned below the real Living Wage in 2019.[4]

Largest employing occupations in the UK, regions and nations (annual population survey, June 2021)

|

Employment by occupation - % |

UK |

North East |

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

East Midlands |

West Midlands |

East |

London |

South East |

South West |

Wales |

Scotland |

Northern Ireland |

|

Business and public service associate professionals |

8.3 |

6.3 |

7.4 |

7.4 |

7.0 |

7.8 |

8.7 |

11.4 |

8.8 |

7.4 |

7.5 |

7.4 |

7.2 |

|

Administrative occupations |

8.3 |

9.0 |

8.6 |

8.1 |

7.5 |

8.9 |

9.4 |

7.7 |

8.3 |

7.8 |

8.6 |

8.0 |

9.6 |

|

Corporate managers and directors |

7.9 |

5.5 |

7.2 |

7.4 |

7.6 |

7.7 |

8.4 |

9.7 |

9.3 |

7.8 |

6.6 |

5.9 |

5.6 |

|

Elementary administration and service occupations |

7.4 |

9.4 |

8.3 |

8.4 |

8.8 |

8.3 |

7.1 |

5.5 |

6.5 |

7.8 |

7.4 |

8.2 |

5.9 |

|

Caring personal service occupations |

7.2 |

8.6 |

7.1 |

7.9 |

8.2 |

8.1 |

6.5 |

5.4 |

7.3 |

7.1 |

8.3 |

7.4 |

7.4 |

|

Science, research, engineering and technology professionals |

7.0 |

4.8 |

6.7 |

6.0 |

6.2 |

6.1 |

6.9 |

8.9 |

8.2 |

6.8 |

4.9 |

7.4 |

7.1 |

|

Business, media and public service professionals |

6.5 |

4.3 |

5.8 |

5.7 |

4.4 |

5.3 |

5.9 |

11.2 |

6.5 |

6.2 |

5.5 |

6.2 |

6.0 |

|

Teaching and educational professionals |

5.2 |

5.4 |

4.9 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

5.6 |

5.1 |

5.2 |

5.5 |

4.6 |

5.3 |

5.2 |

5.5 |

|

Sales occupations |

5.0 |

6.5 |

5.7 |

5.0 |

5.5 |

4.5 |

4.6 |

3.7 |

4.6 |

5.9 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

6.5 |

Source: Annual population survey, regional employment by occupation July 2020-June 2021, accessed via nomis

If low pay in the sectors and occupations that employ large numbers of people across all regions and nations remain low paid is not tackled, communities will not feel that they have been levelled up.

Insecure work

Across the UK, 3.6 million people – one in nine of the workforce - are in insecure work[5]. The table below sets out the main categories of insecure work.

Who is in insecure work?

|

Zero-hours contract workers (excluding the self-employed and those falling |

876,800 |

|

Other insecure work - including agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, |

824,400 |

|

Low-paid self-employed (earning an hourly rate less than the minimum |

1.91m |

|

TUC estimate of insecure work |

3.6m |

|

Proportion in insecure work |

11% |

Source: Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey. The total number in ‘insecure work’ includes (1) agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed – term contracts, (2) workers whose primary job is a zero-hours contract, (3) self-employed workers who are paid less than the minimum wage. See footnote 15 for more details.

These jobs are spread across sectors and are not limited to the digital economy. TUC analysis[6] shows that nearly one in four (23.1 per cent) of those in elementary occupations, including security guards, taxi drivers and shop assistants, are in insecure work. It is the same for more than one in five (21.1 per cent) of those who are process, plant and machine operatives. Very large numbers of those in the skilled trades and caring, leisure and other service roles are also in precarious employment.

Like low pay, insecure work is endemic across every region and nation of the UK. Only Yorkshire and Humber and Scotland have less than one in ten workers in insecure work.

[1] IFS (2019) report ‘Catching up of falling behind? Geographical inequalities in the UK and how they have changed in recent years’ https://ifs.org.uk/uploads/Geographical-inequalities-in-the-UK-how-they-have-changed.pdf (see figure 6 on ‘within-region variation in residents’ mean full-time earnings)

[2] IPPR Analysis of Households Below Average Income 2017/18 – 2019/20 (data refers to the number of people in working families who are in relative household poverty)

[3] Living Wage Foundation (2020) Employee jobs paid below the living wage at https://www.livingwage.org.uk/sites/default/files/Nov%202020%20-Employee%20Jobs%20Paid%20Below%20the%20Living%20Wage%20LWF%20Report_0_0.pdf – this report covers employee jobs only, whereas the workforce data above covers all workforce jobs.

[4] Living Wage Foundation (2020) Employee jobs paid below the living wage at https://www.livingwage.org.uk/sites/default/files/Nov%202020%20-Employee%20Jobs%20Paid%20Below%20the%20Living%20Wage%20LWF%20Report_0_0.pdf – this report covers employee jobs only, whereas the workforce data above covers all jobs.

[5] The total number in ‘insecure work’ includes (1) agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed – term contracts, (2) workers whose primary job is a zero-hours contract, (3) self-employed

workers who are paid less than the National Living Wage (£8.91). Data on temporary workers and zero-

hour workers is taken from the Labour Force Survey (Q4 2020). Double counting has been excluded. The

minimum wage for adults over 25 is currently £8.91 and is also known as the National Living Wage. The

number of working people aged 25 and over earning below £8.91 is 1,910,000 from a total of 4,000,000

self-employed workers in the UK. The figures come from analysis of data for 2019/20 (the most recent

available) in the Family Resources Survey and were commissioned by the TUC from Landman Economics.

The Family Resources Survey suggests that fewer people are self-employed than other data sources,

including the Labour Force Survey.

[6] TUC (11 July 2021) Jobs and recovery monitor – Insecure work https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-monitor-insecure-work

[7] TUC, Living on the Edge: The rise of job insecurity in modern Britain, 2016 https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/living-edge

Insecure work by region

Zero hours contracts have grown significantly in recent years – up from 70,000 in 2006[1] to the levels we see today. Recent polling for the TUC punctures the myth that these contracts offer two-way flexibility to both workers and employers. By far the most important reason respondents gave for taking zero-hours contract work was because that is the only work available. 45 per cent of respondents in a poll of 2,523 workers said that this was the most important reason for them being on zero hours contracts, while just 9 per cent cited work-life balance as the most important reason[2].

Insecure work both reflects and is deepening existing inequalities, with 14.1 per cent of BME workers in insecure work, compared to 10.7 per cent of white workers[3].

Many insecure jobs bear the characteristics of work that are linked by evidence to poor health outcomes, as discussed above in this report. Workers have reported that their medical appointments and social events often have to be cancelled at short notice[4]. Experiences of low levels of control and lack of peer and supervisor support are also borne out by our polling. A separate set of polling reveals that three quarters (75 per cent) of those in secure work would feel comfortable raising an issue with their manager, compared to 60 per cent of those in insecure work[5]. There is also a ten percentage point gap in the proportion of insecure and secure workers who feel safe at work, with 73 per cent of insecure workers feeling safe compared to 83 per cent of those in secure work[6].

Unfortunately, the pandemic seems to have created more uncertainty for insecure workers, not less, with a higher proportion of zero-hours workers in 2021 being offered work or having work cancelled at less than 24 hours' notice compared with 2017[7].

There is a broader pattern of employers seeking to distance themselves from those who work for them. Millions of people cannot enforce their employment rights with the “parent company” they ultimately work for because they work for outsourced companies or franchise businesses or are employed by recruitment agencies, umbrella companies and personal service companies.[8]

There is a particularly stark and growing issue for as many as half a million agency workers who are employed via umbrella companies. As well as facing problems asserting their rights and resolving workplace problems, they can also be the victim of complex wage arrangements that leaves them out-of-pocket and sometimes vulnerable to tax enforcement by HM Revenue & Customs[9].

There is an overlap between jobs that are low-paid and insecure – although as the data above shows, low pay is more extensive than insecurity. There are some geographical differences between the prevalence of each, with Yorkshire and Humberside having the lowest rate of insecure work but rating high in its share of low paid work. These differences will stem from differences in the sectoral and occupational composition of different areas. But despite some variations, the overall picture is that low pay and insecure work are both endemic across every region and nation in the UK.

And many jobs are both low paid and insecure, creating a double whammy for the quality of life of those who do them. The stress caused by the struggle to make ends meet compounded with uncertainty over shifts and pay, the difficulty in planning childcare, let alone a social life, create a toxic mix for those at the bottom end of our labour market.

We need a new approach to level up at work

Much industrial policy has aimed to redistribute better paid jobs more evenly across the country. The government has announced that a new Treasury office will be set up in Darlington, with around a quarter of Treasury staff moving to the new office; the new National Infrastructure Bank will be located in Leeds; and the government has announced plans to move 22,000 civil servants out of London by 2030. Other strategies – relating to skills, transport and other infrastructure policy – aim to make it easier to create and supply good quality jobs in areas that currently don’t have their fair share.

Creating a better distribution of high-skilled, high-paid jobs around the country is an important aim and if successful will improve opportunities for people in parts of the UK where good quality jobs are currently rare. It is a vital part of what is needed to level up. However, if it is not linked to strategies to improve the experience and rewards of low-quality work across all regions and nations of the UK, poverty and insecurity will remain endemic across the country. As well as creating new good quality jobs, we need to level up the jobs that people are already in.

The experience of London shows that the creation and existence of high-paid jobs in an area and does not automatically lead to rising incomes and a better quality of life for the wider community. Indeed, unless low-pay and poverty are also addressed, there is a danger that the creation of high-paid jobs will lead to deepening inequality, unaffordable housing and being priced out of local amenities for many local people. As the table above showed, London has the highest rate of in-work poverty in the country, with 21.8 per cent of people in poverty in a working household. The creation of good quality, green jobs is desperately needed – but it’s not enough on its own.

Levelling up must not replicate and extend the inequality of London. We need to create cohesive communities where every citizen is able to flourish and participate in economic and social life. This means tackling low pay and insecurity wherever they are found and levelling up at work across all regions and nations.

Inequalities: race, gender and disability

If levelling up is to mean everyone having the opportunity of a decent job, we need to tackle all forms of inequality that hold people back. We turn now to the structural inequalities facing black and minority ethnic (BME) workers, women and those with disabilities at work, which overlap with but goes beyond the issues of low pay and insecurity set out above.

The pandemic has highlighted the scale of the structural inequality we face and in many areas deepened it. It has made the case for change stronger than ever. In order to build back better, we need to build back fairer. Equality must be at the heart of any roadmap for levelling up.

[1] TUC, Living on the Edge: The rise of job insecurity in modern Britain, 2016 https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/living-edge

[2] 2021 data: GQR Total sample n=2523, including oversamples of BME workers and people on Zero-Hours Contracts (ZHCs). Fieldwork: 29th January – 16th February 2021

[3] Statistics on insecure work are taken from Jobs and recovery monitor - Insecure work, TUC (2021). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-monitor-insecure-work

[4] TUC (2018) Living on the Edge, TUC p.35 https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/living-edge-0

[5] Polling by BritainThinks for the TUC. All respondents working full / part time May 2021 (n=1972), Nov

2020 (n=2,182); = Insecure (n=110); Secure (n=1851). BritainThinks’ definition of insecure workers does not

include the self-employed.

[6] ibid

[7] 2021 data: GQR Total sample n=2523, including oversamples of BME workers and people on Zero-Hours Contracts (ZHCs). Fieldwork: 29th January – 16th February 2021

2017 data: GQR Research surveyed 300 workers on zero-hours contracts and 2987 other workers, all in Great Britain, online during August 2017. Results were weighted to the national profile of working people, by age, gender, ethnicity, full/part time contracts, public/private sector and industry. The zero-hours sample was separately weighted to national statistics for zero-hours workers, by gender, age, region, full/part-time hours and industry. A summary of the findings can be found here: https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/great-jobs-with-guaranteed-hours_0.pdf

[8] TUC (2021) Shifting the risk https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Shifting%20the%20risk.pdf

[9] TUC (2021) Umbrella companies: Why agencies and employers should be banned from using them https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/umbrella-companies-why… and Low Incomes Tax Reform Group (24 March 2021) Press release: LITRG report puts ‘umbrella’ companies under the spotlight 24 March 2021 https://www.litrg.org.uk/latest-news/news/210324-press-release-litrg-report-puts-umbrella-companies-under-spotlight

BME workers

The impact of coronavirus on BME people has shone a spotlight on multiple areas of systemic disadvantage and discrimination. There have been numerous reports produced over the years – some commissioned by the government itself – that have recommended action to tackle discrimination and entrenched disadvantage.

BME workers experience systemic inequalities across the labour market that mean they are more likely to be unemployed and are overrepresented in lower paid, insecure jobs, as set out in the previous section.

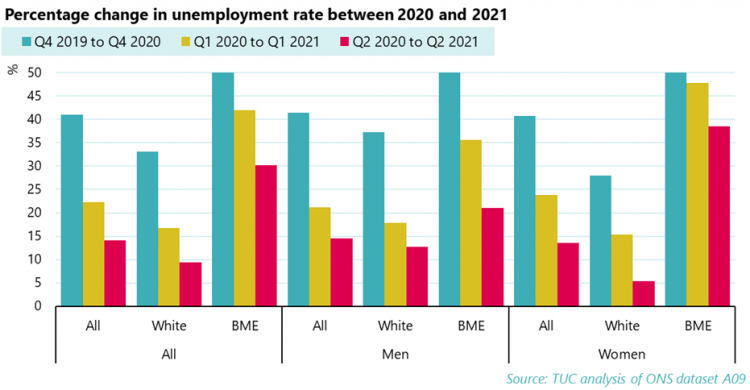

Since the current records began in 2001, the BME unemployment rate has never been less than 69 per cent higher than the white unemployment rate. As the table below shows, this has been worsened by the pandemic, which has had a disproportionate impact on BME unemployment, especially BME women. BME women have seen the starkest rise in unemployment since the start of the pandemic, with the unemployment rate for BME women reaching 10.9 per cent in Q4 2020.

These inequalities are compounded by the discrimination BME people face within workplaces. A poll of BME workers carried out on behalf of the TUC just before the pandemic found that nearly half (45 per cent) said they were given harder or less popular work tasks than their white colleagues[1]. A call for evidence launched by the TUC for BME workers to share their experiences of work during Covid-19 found that of over 1,200 respondents, one in five said they received unfair treatment because of their ethnicity.[2]

The Covid-19 crisis has shown us that this inequality not only limits Black people’s life opportunities through overrepresentation in poor quality work and high levels of unemployment, but also contributes to prematurely ending their lives. We need urgent action to address discrimination in the workplace and the overrepresentation of BME workers in jobs that are low paid and insecure.

Women

Female employees are more likely than male employees to be low-paid. Women make up 50 per cent of employees, but 59 per cent of employees who are paid below £10 per hour[3]. The gender pay gap is currently 15.5 per cent, meaning that the average female worker is paid 15.5 per cent less than the average male worker[4]. While this gap has been narrowing, at the current rate of change it will not close for another two decades.

The introduction of gender pay gap reporting in 2017 was a valuable step forward for women at work, bringing greater transparency to the enduring pay inequality experienced by women. The suspension of pay gap reporting in 2020 and the six-month delay in the requirement to report in 2021 sent a negative message to employers about the importance placed on equality for women in the workplace; equality should not be a side issue to be pushed aside in challenging times.

As TUC reports[5] have highlighted, the pandemic and the government’s response to it have had particular impacts on women, risking turning the clock back on decades of incremental progress.

The pandemic has revealed the fragility of the arrangements that enable mums to maintain employment. For many working mums, a balance of schooling, wraparound care, informal childcare support and annual leave enables them to balance work and care from family and friends with formal childcare and school holiday provision, accompanied by careful arranging of working hours for the adults in the household. In a TUC survey of working mums conducted before the 2021 summer holidays, one in eight respondents said they would have to take unpaid leave over the summer to manage childcare and the same proportion said they would have to reduce hours[6].

Women are almost twice as likely as men to be employed in a key worker occupation (45 per cent, compared to 26 per cent)[7]. Many of the largest key worker occupations have a large majority of female employees, including care workers and home carers, nurses, primary and nursery education teaching professionals and teaching assistants, over 80 per cent of whom are women.

However, as well as well as being more likely to be key workers, women are more likely to be low paid than male key workers. Over four in ten (41 per cent) of female key workers are paid less than £10 per hour, compared with around one in three (32 per cent) of male key workers.

We need action now to address the persistent under-payment of women in the labour market and to give working mums and dads the flexibility they need to balance work with their responsibilities as parents.

Disabled workers

Before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, disabled workers faced huge barriers getting into and staying in work, resulting in significant employment and pay gaps compared with non-disabled workers.

In 2019/20, the employment rate for disabled people was 53.7 per cent, compared to 82.0 per cent for non-disabled people - an employment gap of 28.4 percentage points[8]. This means that disabled workers are much more likely to be unemployed, with the unemployment rate for disabled people currently double that of those without disabilities (8.1% compared to 3.8%).

While the disability employment gap narrowed slightly in 2019/20, the disability pay gap was widening. In 2018/19, non-disabled workers earnt £1.65 (15.5 per cent) more per hour than disabled workers. In 2019/20, this increased to £2.10 (19.6 per cent). Disabled women face the biggest pay gap, being paid £3.68 an hour less than non-disabled men[9].

Disabled workers face significant difficulties in accessing reasonable adjustments in the workplace, despite the fact that all employers have a legal duty under the Equality Act 2010 to make reasonable adjustments to address any disadvantages that disabled workers face. The law recognises that to secure equality for disabled people work may need to be structured differently, support given, and barriers removed.

However, TUC research found that before the pandemic, over four in 10 (45 per cent) of disabled workers who asked for reasonable adjustments failed to get any or got only some of the reasonable adjustments they asked for[10]. And the difficulties disabled workers face accessing reasonable adjustments continued during the pandemic, with almost half (46 per cent) of those who requested them failing to get all or some of the reasonable adjustments they needed to work effectively. Both before and during the pandemic, over two in five disabled workers were not told by their employers why their request for adjustments had not been implemented (44 per cent before the pandemic, 41 per cent after)[11].

The pandemic, and the huge changes it has caused to our everyday lives, have exacerbated the barriers disabled people face. Not only have disabled people been disproportionately affected in terms of loss of life, with six in 10 Covid-19 related deaths being disabled people[12], but pre-existing workplace barriers have been accentuated by the pandemic. We need urgent action to address disability employment and pay gaps and ensure that disabled workers have access to the reasonable adjustments they need.

[1] Poll findings and call for evidence findings mentioned in this section are taken from Dying on the Job, TUC (2020). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/dying-job-racism-and-risk-work

[2] ibid

[3] A £10 minimum wage would benefit millions of key workers, TUC (2020). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/ps10-minimum-wage-would-benefit-millions-key-workers

[4] Gender pay gap in the UK: 2020, ONS (2020). Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/bulletins/genderpaygapintheuk/2020

[5] Working Mums: Paying the Price available at https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-04/WorkingMums.pdf

Forced Out: The cost of getting childcare wrong available at: www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/ForcedOut2.pdf

[6] Summer holiday childcare: no let up for working mums, TUC (2021). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/summer-holiday-childcare-no-let-working-mums

[7] A £10 minimum wage would benefit millions of key workers, TUC (2020). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/ps10-minimum-wage-would-benefit-millions-key-workers

[8] The disability pay gap and disability employment gap is calculated by a TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey statistics from 2019 Q3 and 4, and 2020 Q1 and Q2. More details can be found in Disability pay and employment gaps, TUC (2020). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/disability-pay-and-employment-gaps

[9] ibid

[10] Disabled workers’ experiences during the pandemic, TUC (2021). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/disabled-workers-experiences-during-pandemic

[11] Disabled workers’ experiences during the pandemic, TUC (2021). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/disabled-workers-experiences-during-pandemic

[12] ONS Updated estimates of coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by disability status, England: 24 January to 20 November 2020 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronaviruscovid19relateddeathsbydisabilitystatusenglandandwales/24januaryto20november2020#overview-of-covid-19-related-deaths-by-disability-status

We need to change the way our economy works and the incentives that shape it so that economic growth translates into good quality jobs. This requires an institutional environment that encourages the development of business models based on high-wage, high-skilled and secure jobs, rather than a reliance on low-paid and insecure work. Without reforms that hard wire decent work into business models, strategies to boost research and development and attract new investment, while welcome, will not deliver the good jobs people need.

This requires the development of a new skills strategy that gives people rights to training and development throughout their working lives. It also requires reforms to our corporate governance system so that companies are encouraged to focus on long-term, sustainable growth that distributes a fair share to workers, rather than prioritising short-term returns to shareholders. We need new measures to strengthen workforce voice and collective bargaining to give working people more power in the workplace. And we need to develop a new, green industrial policy with effective measures for creating and supporting good quality jobs in sectors that will equip the UK for the transition to net-zero and trade policies that will raise employment standards in the UK and around the world.

A skills strategy for all workers

The government has acknowledged the contribution of skills policies to the levelling up agenda. However, the policy framework set out in the skills white paper[1] earlier this year comprises a very modest set of proposals that will do little to tackle either the immediate problems created by the pandemic or the long-term weaknesses in our skills system. Looking beyond the immediate skills shortages created by Brexit and the pandemic, there are huge skills challenges on the horizon which require a new scale of ambition and new policy solutions that go beyond the white paper proposals.

The TUC is calling for a new national lifelong learning and skills strategy based on a vision of a high-skill economy, where workers can quickly gain both transferable and specialist skills to build their job prospects. Some key measures could be rolled out swiftly now, with longer-term reforms put in place to tackle entrenched failings in our skills system that limit employment prospects and personal development. A strategic approach along these lines could be delivered at pace by a National Skills Taskforce that would bring together employers, unions and other key stakeholders along with government.

Key challenges in our skills system

Not everything that is presented as a skills shortage can be solved through skills policy alone. As the current shortage of HGV drivers has shown, labour shortages can be created by poor wages and working conditions that make jobs unattractive and increasingly unviable for staff. A recent review by the Labour Research Department[2] shows how companies are increasingly forced to compete for transportation contracts on costs alone, driving down wages and conditions, and creating a situation where many drivers are forced to pay for their own training as well as essentials such as overnight parking facilities. LRD highlights examples of best practice in the logistics and other sectors, where employers and unions have agreed deals on pay, training and other matters to tackle growing labour and skills shortages. This demonstrates the importance of addressing working conditions through collective bargaining in solving skills and labour shortages.

We do, however face significant long-term challenges in our current skills system. A major concern is that participation in lifelong learning and training is in long-term decline, while economic and social trends are requiring workers to upskill and retrain more than ever before. As well as the immediate skills challenges created by the pandemic and Brexit, we face the longer-term challenges of automation, AI and the transition to a greener economy. The Green Jobs Taskforce[3] highlights that one in five jobs in the UK (approximately 6.3 million workers) will require skills for new green occupations and to upskill and retrain those in high-carbon jobs.

An associated trend is that those most in need of training are least likely to access it from their employer and this has been amplified further by the pandemic. A recent analysis by the Learning & Work Institute[4] found that employer investment in training fell more sharply during the pandemic than following the last global financial crisis. The groups facing the sharpest fall in training include adults with lower-level qualifications, young workers in the private sector and apprentices. This encompasses large numbers of the jobs in relatively low-paid work that have borne the brunt of job losses triggered by Covid-19.

Another area of concern is our poor record in supporting young people and adults to progress to intermediate and higher-level technical skills. There is broad support for developing quality post-school pathways to apprenticeships and technical qualifications with the same esteem as the HE route. But we are a long way from achieving this. While many of our apprenticeships are world-class, too many young people are not enjoying the quality employment and training experience that is the norm in apprenticeship systems in other countries. We also compare poorly when it comes to offering both school leavers and adults the opportunity to progress to higher-level technical qualifications that have an equal status to university degrees.

There are four key areas of reform that should be at the heart of a lifelong learning and skills strategy to address these challenges:

· A significant boost to investment in learning and skills by both the state and employers is essential.

· People should have access to fully-funded learning and skills entitlements and new workplace training rights throughout their lives, expanding opportunities for upskilling and retraining.

· We need a national social partnership, bringing together employers, trade unions and government, to provide clear strategic direction on skills - as is the case in most other countries.

· Our college workforce must be empowered and properly rewarded for their work; an immediate priority must be to tackle the long-term decline in pay in the sector.

More detail on each of these themes is set out below.

A boost to skills investment

State and employer investment in skills, particularly for adults, has been in long-term decline for many years. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), government funding for adults attending college courses was halved in the last decade and new spending on the National Skills Fund will reverse only one third of this reduction.[5] There are similar trends affecting post-16 education and training, with the IFS predicting that an extra £570m per annum will be required by 2022-23 just to maintain spending per student in real terms for 16-18-year-olds in colleges and sixth forms.[6] TUC research[7] has highlighted that job-related training provided by employers has been in decline since the mid-1990s and this trend intensified during the pandemic. UK employers invest just half the EU average in training; if investment per employee equalled the EU average, there would be an additional £6.5 billion spent each year.[8]

A national lifelong learning and skills strategy should contain an explicit boost to FE and skills funding over a multi-year period and this long-term funding picture should be updated regularly.

A right to life-long skills and learning entitlements

With 80 per cent of the projected 2030 workforce already in the labour market, it is clear that we need to enable many more workers to access learning and training. However, the government’s current “lifetime skills guarantee” is significantly weaker than the adult skills entitlements that were abolished nearly ten years ago and is too restrictive to bring about the step change we need.

The guarantee applies only to a prescribed list of level 3 qualifications only. But many adults need access to free courses for foundation and level 2 qualifications in order to progress to take-up of the level 3 entitlement, which are not covered. In addition, many adults in need of retraining are excluded because they already hold a level 3 qualification, even if this is from decades earlier – making a mockery of the concept of a lifetime skills guarantee.

The TUC is calling for a package of measures to give a real boost to lifelong learning for adults. In the first instance, a wider range of skills entitlements for adults and a new “right to retrain” should be established. Over time these entitlements should be incorporated into lifelong learning accounts that would facilitate additional workplace learning, encouraging co-investment by employers. We should also follow the examples of other countries that have introduced rights for workers to paid time off for education and training and access to regular skills reviews in the workplace. OECD research[9] has shown that combining initiatives, such as lifelong learning accounts, with new workplace training rights has proved effective in countries adopting this approach. The government should also draw on the experience of other countries that have permanent short-time working programmes[10] and roll out a scheme that provides funded training to any workers who are working less than 90 per cent of their normal working hours.

Apprenticeships and young people

While investment in apprenticeships has been boosted by the levy, the number of opportunities has been declining in recent years, especially among the youngest apprentices and disadvantaged groups. According to a recent analysis[11] by the IFS, the number of 16- and 17-year-old apprentices fell by 30 per cent between 2019 and 2020 and only 3 per cent of this group took up an apprenticeship in 2020. IFS estimates this to be the lowest level “since at least the 1980s and almost certainly a lot longer” and that there is a real risk this could become a permanent trend. Analysis by the Social Mobility Commission has also shown a long-term decline in apprenticeship places for young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds.[12] The TUC agrees with IFS that “there are few policy reforms or incentives in place to arrest” the decline in apprenticeships and to widen access.

The forthcoming review of the apprenticeship levy offers an opportunity to tackle these challenges. The TUC will be calling for changes to enable employers to use this funding in a much more flexible way. For example, there is a strong case for allowing employers to use levy funding for innovative pre-apprenticeship programmes and other initiatives aimed at boosting take-up, particularly of under-represented groups. But we will also be calling for wider policy reforms beyond the remit of the levy. There is a pressing need for government to enforce existing regulations and introduce new requirements of employers and training providers in order to tackle the continuing high incidence of poor-quality training, exploitative employment practices, low wages, and limited progression routes currently blighting our apprenticeship system.

Social partnership and union learning

Trade unions and their union learning reps have years of expertise and experience that should be drawn on to boost take-up of new skills entitlements in the workplace. The Green Jobs Taskforce has recognised this in its recent report[13], calling on more employers to recognise “union learning representatives, in order to increase access to training for hard-to-reach employees” needing upskilling and retraining. It is also notable that the latest annual skills analysis by the OECD[14] refers to the work of unionlearn and union learning representatives as an outstanding example of “proactive initiatives undertaken in OECD countries to engage low-skilled adults to participate in adult learning”.

As the OECD has highlighted, the UK lacks the institutional partnership of employers and unions that works so effectively in other countries to govern quality skills systems. This gap was emphasised by a recent report on levelling up skills after the pandemic [15] and by the Industrial Strategy Council in one of its last reports on skills, which noted that the role of employer and employee organisations in other countries is of great benefit to the stability and quality of their skills systems.[16] Despite these findings, there is not one mention of unions in the skills white paper.

This is a missed opportunity to harness the expertise of workforce representatives which, if not rectified, will hold back the development of an effective skills policy able to benefit both workers and the economy. We need a new national social partnership on skills to provide clear strategic direction, as is the case in most other countries. Trade unions will also continue to play a vital role by supporting young people and adults to upskill and retrain in the workplace

FE workforce

The skills white paper does include a section on supporting the development of the FE workforce but there is no acknowledgement that years of pay cuts and growing casualisation have demoralised college workers and undermined their status. On pay, the latest statistics show that there is a £9,000 pay gap between teachers in schools and colleges and the FE unions have highlighted that all college staff have suffered a real-terms pay cut of 30% since 2009[17]. The issue of FE pay has been highlighted as a priority by the two most important independent reviews of FE in recent years, the Augar Review and the Independent Commission on the College of the Future. The Commission recommended a new starting salary of £30,000 for teaching staff in colleges to tackle the pay gap with schools and called for a national social partnership between government, the Association for Colleges and trade unions to look at long-term strategic challenges facing the whole FE workforce, recommendations that the TUC and FE unions support.

The long-term decline in FE sector pay must be tackled as a matter of urgency, with an immediate and significant move towards restoring college pay levels to 2009 levels in real terms. Going forwards, we need to make sure our college workforce is properly valued, with contracted-out services brought back in house and no worker paid less than the Real Living Wage.

Corporate governance reform to promote long-term, sustainable growth

Our corporate governance system plays a key role in shaping the discussions and priorities of the boardroom and how companies are run. Company law and other soft law requirements, such as the Corporate Governance Codes, have a direct impact on the business models and employment practices adopted by companies. Corporate governance reform is an important part of creating a stronger, fairer economy where working people receive a fairer share of the wealth they create. Increasing investment is not enough; we need to change the way companies operate so that investment translates into good quality work.

Reform of shareholder primacy

The UK’s corporate governance system prioritises the interests of shareholders over the interests of all other stakeholders and arguably over the long-term interests of the company itself. A report by the TUC and High Pay Centre[18] found that between 2014 and 2018, returns to shareholders grew by 56%, nearly seven times more than the median wage for UK workers, which increased by just 8.8% (both nominal). If pay across the UK economy had kept pace with shareholder returns, the average worker would be over £9,500 better off.

The priority given to shareholder returns leads to companies paying dividends even when not justified by company performance. Our report found that in 27% of cases, returns to shareholders were higher than the company’s net profit, including 7% of cases where dividends and/or buybacks were paid despite the company making a loss. In 2015 and 2016, total returns to shareholders came to more than total net profits for the FTSE 100 as a whole.

Overall, profits varied significantly more than returns, with profits ranging more than twice as much as returns over the period. This contradicts the idea that shareholders are exposed to the greatest risk of all business stakeholders, as it suggests that they can expect consistent returns, regardless of profitability.

The priority given to shareholders in corporate governance is often justified by the argument that shareholders carry the greatest risk in relation to company performance. This argument is contradicted by the reality of share ownership patterns today. Institutional shareholders hold highly diversified portfolios with shareholdings in hundreds, if not thousands, of companies across different geographies precisely to spread their risk. Workers, on the other hand, invest their labour, skills and commitment in the company they work for, and cannot diversify this risk. Few workers can simply walk from one job into another and if their company fails for any reason workers and their families pay a heavy price – the loss of employment and income, skills, confidence and health that this can bring.

As well as squeezing wages, the priority given to shareholder returns hampers investment in R&D. Research for the Bank of England found that the most important reason for under-investment was a constraint on using profits for investment purposes, with three quarters of firms rating distribution to shareholders (including dividends and share buybacks) and purchase of financial assets (including mergers and acquisitions) ahead of investment as the most important use of internally generated funds. Strikingly, 80 per cent of publicly owned firms agreed that financial market pressures for short-term returns to shareholders had been an obstacle to investment[19]. This demonstrates how the role of shareholders in the UK’s corporate governance system contributes to under-investment and short-termism.

· To address shareholder primacy, directors’ duties should be reformed so that directors are required to promote the long-term success of the company as their primary aim, taking account of the interests of stakeholders including the workforce, shareholders, local communities and suppliers and the impact of the company’s operations on human rights and on the environment.

Worker directors on company boards

In addition to removing shareholder primacy in company law, we need reform of board composition to change the culture and priorities of the boardroom and improve the quality of board decision-making.

There is strong evidence that more diverse boards make better decisions. The TUC supports measures to promote greater gender and ethnic diversity on boards.

It is vital that measures to promote diversity includes a focus on social diversity and diversity of role and experience. The TUC strongly supports measures to include workers directors on company boards. Worker directors would bring people with a very different range of backgrounds and skills into boardrooms, helping to challenge ‘groupthink’. It is clear from the minority of UK companies with worker directors and from evidence from countries where worker directors are common that bringing the perspective of an ordinary worker to bear on boardroom discussions is particularly valued by other board members.

Workers have an interest in the long-term success of their company and their participation would encourage boards to take a long-term approach to decision-making. They would bring direct experience to bear on the important area of workforce relationships, a key area for company success.