BME women and work

Black and minority ethnic (BME) women are around twice as likely as white workers to be employed in insecure jobs, according to a TUC analysis.

The analysis shows that around 1 in 8 (12.1%) BME women working in the UK are employed in insecure jobs compared to 1 in 16 (6.4%) white women and 1 in 17 (5.5%) white men. The TUC says that many of these roles are in vital front-line services like health and social care.

TUC body demands government takes action to tackle structural racism

Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic, and our government’s response to it, represent a serious threat to equality at work. Pre-existing inequalities have been highlighted and deepened. The social and economic impacts of pandemics fall harder on women than men.[1] Since the Covid-19 crisis began, women have borne the brunt of meeting rising care needs, providing unpaid care for children, friends and family.[2] They are at increased risk of domestic abuse, face restrictions accessing sexual health and family planning services and are more likely to be affected by job losses at a time of economic instability.[3] This is particularly the case for BME women who face intersecting systems of oppression across their multiple identities that compound one another. These intersections include disability, gender identity, and sexual orientation, class, nationality, migration status, and faith.

BME women experience systemic, structural inequalities across the labour market that mean they are overrepresented in lower paid, insecure jobs and at higher risk of being underemployed:[4]

- Insecurity: One in eight BME women are in insecure jobs compared to one in eighteen white men

- Low pay: Three out of five BME women in self-employment are low paid compared to two out of five white men

- Underemployment: One in eight BME women are under-employed compared to one in thirteen white men

These inequalities are compounded by the distorting lenses of stereotyping and prejudices about race, gender and class that BME women are often seen through. That leads to discrimination and unfair treatment in the workplace that holds BME women back and has a profound impact on their mental and physical health. As we have seen during the Covid-19 pandemic, the cumulative impact of that discrimination and disadvantage can cost BME women their lives.[5]

- Unfair treatment: Close to half (45 per cent) of BME women say they have been singled out for harder or unpopular tasks at work compared to their white counterparts

- Discrimination: Almost one third (31 per cent) of BME women report being unfairly passed over for or denied a promotion at work, this rose to nearly half of disabled BME women (45 per cent)

- Racism: More than one in three (34 per cent) BME women have experienced racist jokes and so-called banter at work and 30 per cent have experienced verbal abuse

This briefing brings together evidence and data from a range of sources including:

- An ICM survey commissioned by the TUC in February 2020 involving 1250 BME workers, three-fifths of respondents were BME women

- Responses to TUC’s call for evidence issued in June 2020 with 1,670 responses

- A poll conducted by Britain Thinks on behalf of TUC involving over 2,000 workers, with sufficient representation of BME workers to make the results nationally representative[6]

- TUC analysis of labour market trends by ethnicity and gender using the Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

Action is urgently needed to combat the racism and discrimination BME women face in the workplace and to prevent a roll back on BME women’s hard-won rights and progress in the workplace.

In order to identify effective solutions to the issues highlighted in this report, it is crucial we centre the voices of those workers who experience structural and individual racism and sexism at work on a daily basis. BME women trade unionists have been at the forefront of the fight for equality and they must be again now. BME women at work need a range of measures and actions, urgently. Those solutions must be led by BME women with their needs and voices centred. The TUC will be working with BME women trade unionists to drive this forward.

Casualisation at work

BME women are overrepresented in insecure jobs. One in eight (12.1 per cent) are insecurely employed compared to one in sixteen white women (6.4 percent). BME men and women are overrepresented in other forms of insecure work, such as low paid self-employment, compared to their white counterparts. One in six BME men (17.1 per cent) and one in seven BME women (14.6 per cent) are in insecure work (that is, including both those employed and self-employed) compared with one in ten male and female white workers.[1]

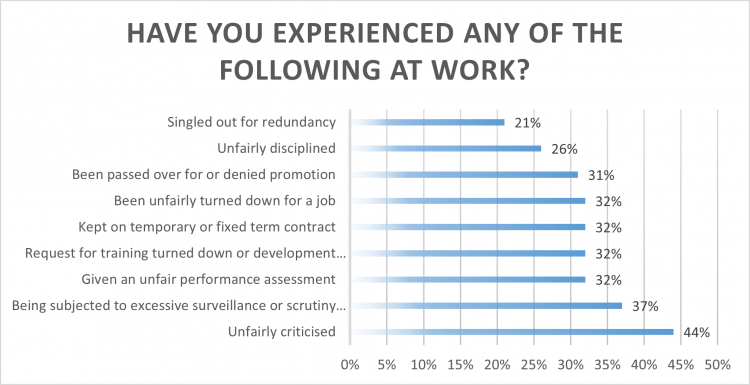

While working in insecure jobs is often claimed to be a choice, nearly one-third of BME women (32 per cent) we spoke to said they had been kept on an insecure or temporary contract despite wanting more security at work.[1]

BME women in insecure work often have little control over the hours they work and how often, creating huge financial uncertainty, anxiety and stress. The unpredictability of their take-home pay makes it increasingly difficult to plan financially, to access credit, and to secure mortgages or tenancy agreements. Constantly varying working hours also has an impact on family life, making it difficult for women to organise childcare, the care of older relatives and a social life.

Due to their uncertain employment status, the transient nature of their work and their low level of weekly pay, many BME women working on zero-hours or agency contracts lose out on basic rights at work such as the right to sick pay, right to paid leave and protection from unfair dismissal. Protections that are vital during a crisis like the Covid-19 pandemic.

Lack of workplace rights, and the knowledge that hours can be reduced or temporary contracts not renewed, shapes the workplace experience of BME women in insecure work. The stress and uncertainty created by the unpredictable nature of insecure work blights the lives of workers in ordinary times. But the Covid-19 pandemic has added a more deadly aspect to this lack of workplace power and protection. BME workers have told the TUC they are frequently denied access to PPE and to appropriate risk assessments.[2] As one BME woman explained when asked to do visits to the vulnerable and elderly during the pandemic.

My other colleagues refused, I am still under a short-term contract and don't have similar rights as they did to refuse to do tasks.

One nurse employed on an agency contract told us that she was always allocated to work with the patients with coronavirus, something that didn’t happen to white colleagues. When she asked if staff could be rotated so that no one person was always looking after coronavirus patients, her manager exploited her insecure status as an agency worker, threatening to inform her agency and stop booking her for work if she didn’t stop raising these issues. She was then faced with a stark choice between being able to earn an income and continuing to be placed at increased risk which could threaten her life.

I had to make a decision to either die on the job or move away quietly to save my dignity and health.

For BME women in this situation, their choices are often constrained by external factors. A decade of austerity and changes to taxes, benefits and public spending on services have disproportionately impacted BME women.[1] Women are more impacted by cuts to the social security system and public services as a result of structural inequalities which means they earn less, are less likely to own their own home or car and have more responsibility for unpaid care and domestic work. These gender inequalities intersect with racial inequalities that have resulted in BME families in the poorest fifth of households experiencing a drop in living standards by over £8,400 a year because of austerity changes.

The government’s hostile environment policy, which set out to make staying in the UK as difficult as possible for those without leave to remain, has left many BME workers with no recourse to public funds,or at the mercy of unscrupulous employers who know that because of arbitrary changes in immigration rules they are now undocumented. A recent Citizens Advice research revealed nearly 1.4 million people have no recourse to public funds.[2] This places them at much higher risk of working in unsafe conditions and means many BME migrant women have no choice but to work, often in multiple precarious jobs, despite risks to their health.

Pay for BME women in work

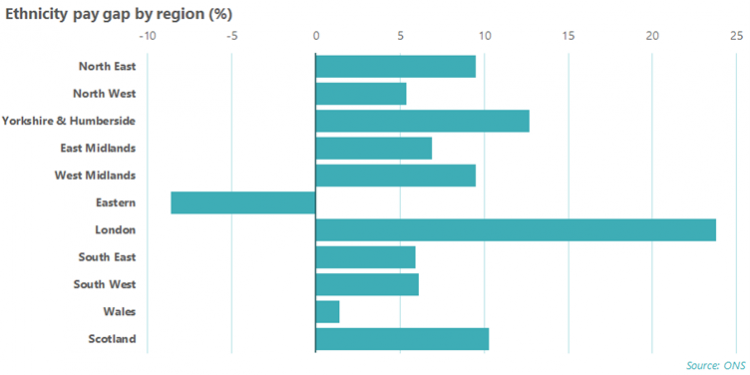

BME workers are overrepresented in the lowest paid occupations and underrepresented in the highest paid occupations.[3] Recent ONS data shows an average ethnicity pay gap of 2.3 per cent.[4] However, this figure hides significant regional variations. London has the highest ethnicity pay gap at 23.8 per cent.[5]

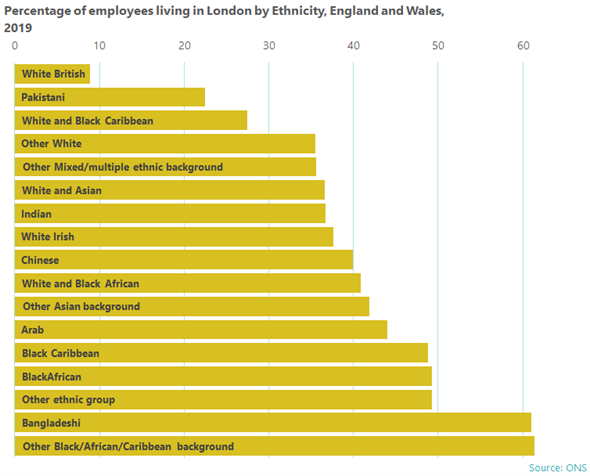

The capital also has the highest density of BME workers. Almost 50 per cent of Black African (49.3 per cent) and Black Caribbean (48.8 per cent) workers and 61 per cent of Bangladeshi workers work in London. However, despite the sizable pay gap experienced by a significant proportion of BME workers, the higher average wage in the capital means that this isn’t reflected in the overall national figure. The national figure of 2.3 per cent which has been lauded as a marker of progress[1] hides stark inequalities for many BME workers.

The causes of pay gaps are complex but for BME women they are shaped by race and gender inequalities as well as other determinants such as age, class and disability. Despite evidence of significant ethnicity pay gaps, only gender pay gap reporting is mandatory in the UK. It is impossible to tackle the gender pay gap without understanding and taking targeted action to address the ethnicity pay gap and any other gaps such as the disabled workers’ pay gap.[1] The pay gap for disabled women is 25.9 per cent, significantly higher than the overall gender pay gap of 17.3 per cent. Without mandatory monitoring and publishing of ethnicity pay gaps, alongside disability pay gaps, it will be impossible to effectively tackle the gender pay gap.

BME women employed in precarious jobs tend not only to experience heightened job insecurity but also a significant pay penalty. Pay in temporary and zero-hours jobs is typically a third less an hour than for those on permanent contracts.[2] This is also the case for self-employed BME women.

In the last decade, the UK has witnessed a rapid expansion in self-employment. The experiences that different BME groups have of self-employment suggest that this is often a route taken as a solution to the barriers they have experienced in the labour market. There is a concern that many women are only taking this kind of work because they are unable to find good quality employee jobs that provide the stable employment they want and the growth of self-employment is taking place at the expense of more secure employee jobs. Many newly self-employed workers do the same work as employees but with less job security and often less take-home pay. TUC analysis has revealed 60 per cent of self-employed BME women are low paid,[3] compared to 48 per cent of white women and 42 per cent of white men.

Many women work extra hours to make up for low pay but this option is not open to all. Some are denied more hours at work while other women with children or caring commitments may be unable to work additional hours because of factors such as a lack of affordable or accessible childcare provision or inadequate social care services.

Progression of BME women in work

Due to structural racism, sexism and discrimination, BME women entering the labour market are often forced to take jobs well below their qualification level.[1] Occupational differences appear across all levels of seniority within the labour market but are starkest in the highest paid, leadership roles, where BME women are seriously underrepresented.

- Leadership: Across the public and private sector just 1.5 per cent of the 3.7 million business leaders are from a BME or ethnic minority background[2]

- Business: Women make up just over one in 20 chief executives of FTSE 100 companies. None are BME women[3]

- Public sector: Only a fifth of senior civil servants participating in the Civil Service Board are women (21 per cent) and just over a third of permanent secretaries (35 per cent). There are no BME women in these roles[4]

BME women’s pay and career progression out of low-paid, entry-level positions is held back by a range of barriers. A 2017 survey by the then teachers’ union NUT, now NEU, and Runnymede Trust found BME teachers face a mixture of visible and invisible barriers that stunt their career progression.[5]

Structural barriers such as racism, including assumptions about capabilities based on racial/ethnic stereotypes, were everyday experiences for BME teachers. In particular, BME teachers spoke about an invisible glass-ceiling and widespread perception among senior leadership teams (SLTs) that BME teachers “have a certain level and don’t go beyond it.

BME workers are more likely to say unfair treatment and discrimination at work negatively impacts their career prospects and pay than white workers, (19 per cent and 11 per cent respectively).[6] A 2017 TUC poll of BME workers found 19 per cent had been unfairly denied training or promotional opportunities at work. [7] This is intensified for BME women who face a toxic combination of both racism and sexism in the workplace.

BME women told us about the types of discrimination and unfair treatment they face that include being unfairly turned down for a job, denied training opportunities and unfairly disciplined or criticised. Close to one in three BME women (32 per cent) we spoke to said they had been unfairly turned down for a promotion.[1] This was particularly the case for disabled BME women (48 per cent) and for BME women aged 18 to 25 (37 per cent).

Fair and transparent routes for career progression are therefore important to BME women. In a poll conducted by the TUC, BME workers (21 per cent) were much more likely to say career progression opportunities in a job were important to them than white workers (12 per cent).[1] A survey conducted by Business In The Community found that 74 per cent of BME workers want to progress in their career compared to 42 per cent of white employees. [2] However, one-third of BME workers feel their ethnicity will be a barrier to their next career move, compared to only 1 per cent of white employees.[3]

BME women also face discrimination that prevents them from even being in a position to apply for promotion in the first place, such as being denied equal training and development opportunities. In our survey of BME women, just under one-third of BME women said they had been unfairly denied access to training and development opportunities. This rose to one in two BME disabled women (52 per cent) and 38 per cent of BME women aged 25 to 34.

It is not simply the case that even when BME women overcome the barriers they face, they can progress unhindered. As we noted at the start of this section, even when BME women do progress at work, the evidence suggests they continue to experience significant pay gaps compared with their white peers. BME workers with degrees earn 23.1% less on average than white workers with degrees.[4]

Occupational segregation

BME women workers, particularly those from Indian, Black African and Black Caribbean backgrounds are over-represented in key worker jobs, especially front-line health and social care roles, compared to white workers.[5] At the same time, across all ethnic groups, women are over-represented in key worker roles compared to men. This has put BME women at increased risk during the Covid-19 pandemic. As our report, Dying on the Job: Racism and Risk at Work, showed, throughout the crisis, BME workers have been singled out for higher risk work, denied access to PPE and appropriate risk assessments, unfairly selected for redundancy and furlough and experienced hostility from managers if they raised concerns.

In May 2020, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) published an analysis of the number of Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers that had died because of Covid-19, revealing the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on BME people. The analysis shows that when taking into account age, Black women are 4.2 times more likely than white women to die from coronavirus.[6] Women from a Bangladeshi or Pakistani background have a coronavirus fatality rate 3.7 times higher than that of white women.

Underemployment

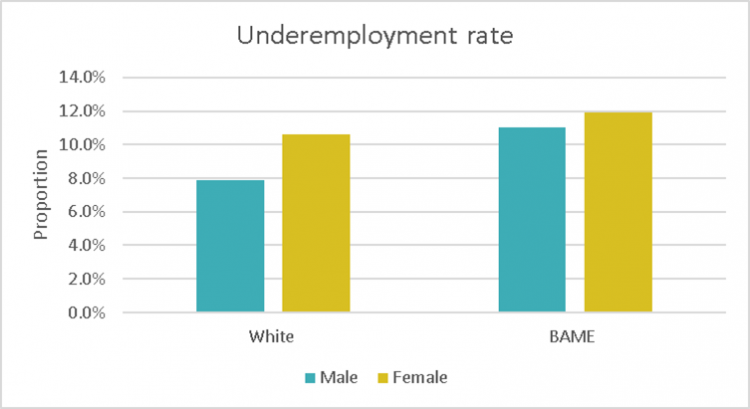

Inter-linked with the spread of casualisation, falling wages and rising costs of living has been the growth in under-employment, which the TUC defines as those in work not getting the hours they want. BME workers are twice as likely as white workers to report not having enough hours to make ends meet.[7]

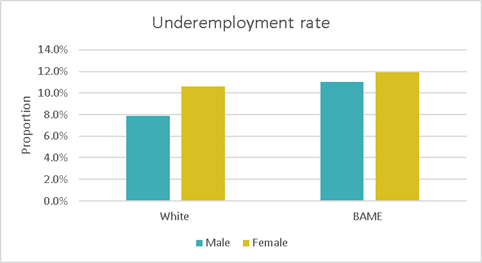

Using the TUC definition of underemployment[1] ,the overall underemployment rate stands at 9.5 per cent, around one in ten workers.[2] Women are more likely to be underemployed than men and BME workers are more likely to be underemployed compared to white workers. BME women are the most likely to be underemployed, with one in eight BME women (11.9 per cent) underemployed.[3]

Prior to the crisis, women on zero-hours and agency contracts were the most likely to say they had been denied sufficient hours at work.[4]

- More than half (58 per cent) of BME women on zero-hours contracts and 30 per cent of those on agency contracts said they had not been given sufficient hours at work

- BME women aged 18 to 25 were most likely to say this had been the case, with 37 per cent saying they had been denied hours at work

This suggests household incomes for BME women in insecure work were already under financial pressure prior to the Covid-19 crisis. Many BME women have to work multiple precarious jobs in order to make up the level of income they need. Since the pandemic started, working hours across all sectors have seen the biggest fall since records began, intensifying pre-existing difficulties experienced by BME workers.[5] This has reduced household incomes and deepened the financial strain on BME women and their families.

Discrimination and unfair treatment

As our report, Racism Ruins Lives,[6] showed institutional racism has a cumulative impact on BME worker’s health, wellbeing and ability to function at work. The physical and psychological consequences for BME workers experiencing racism or working in a hostile environment are significant. The insidious and institutionalised nature of racism and sexism at work can undermine BME women’s careers, leave them feeling isolated from colleagues at work and have a negative impact on their relationships with families and friends. As one BME women, working in the public sector, told the TUC[7]

“You can never absolutely prove it…It’s insidious. The ignoring you is as bad as the shouting at you…I ended up on anti-depressants and suicidal. It makes you forget who you are, your strengths, your abilities. I’m a skilled intelligent woman who’s worked for 35 years and I ended up barely able to send an email. It’s like the perpetrators don’t realise. Leaves you powerless. I’m having to leave my job and take a £10k wage reduction for a short-term post instead of my permanent one. It’s either that or my life.”

Racism is rife in the workplace, as TUC’s survey of BME women revealed:[8]

- Over one in three BME women (34 per cent) had heard racist jokes or so-called ‘banter’

- Just under one third of BME women (32 per cent) had been bullied or harassed at work

- 29 per cent had been subject to racist remarks directed at them or others in the workplace or witnessed racist verbal or physical abuse of others in the workplace or at work-organised social events

BME women face the double disadvantage of both race and sex discrimination in the workplace. In a separate survey conducted by the TUC, 37 per cent of women reported that race and gender was the reason for the verbal abuse they received. The TUC’s report on sexual harassment ‘Still just a bit of banter?’ showed that BME women’s experience of sexual harassment is often bound up with racial harassment.[1]

Previous studies by the TUC have collected a whole swathe of examples whereby BME women were expected, if not coerced, into conforming to white aesthetic norms at work.[2] This was most evident in relation to workplace encounters centring on BME women’s hair. A considerable number of women identifying as BME reported that they had been pressurised, and in some cases explicitly forced, to ‘straighten’ their hair, as well as being objectified in hypersexualised ways.

“People constantly wanting to touch my Afro Hair” (Female, Customer service role)

“After getting my hair done over the weekend, my manager asked if she could touch my hair. And when I later pointed out how this might have been unacceptable, she justified herself by saying ‘I only asked to feel it because it’s fake’. On another occasion the same person made a flippant remark about how a ‘5’8 BME woman, that’s scary’. My current line manager alleged that she perceived me as being ‘threatening’ and ‘intimidating’ because I often ask questions in meetings” (BME woman, Arts)

“I have been touched and petted like an animal by complete strangers in the workplace. Made to feel like a curiosity” (BME woman, Customer Service)

As well as BME women having to conform to white aesthetic norms, BME women within the trade union movement have for many years raised concerns about cultural stereotyping by employers. Different groups of BME women may be alternatively characterised as overly passive and lacking confidence within the workplace or being too aggressive and confrontational.[3] While stereotypes may vary, both essentially render these women as being viewed as unsuitable or unready for progression within the workplace.

Other groups of women have difficulty even accessing the workplace. It is often suggested that Pakistani and Bangladeshi women exclude themselves from the labour market - through their lack of skills or a reluctance to engage outside their culture. In 2006, the Equal Opportunities Commission addressed this issue with research that found Bangladeshi and Pakistani women faced “discrimination at work, low expectations and stereotyping” that excluded them from the workplace.[4] Research conducted by the Runnymede Trust over a decade later shows that the significant gendered-element of Islamophobic hate crime and discrimination continues to limit many women’s life and work choices.[5]

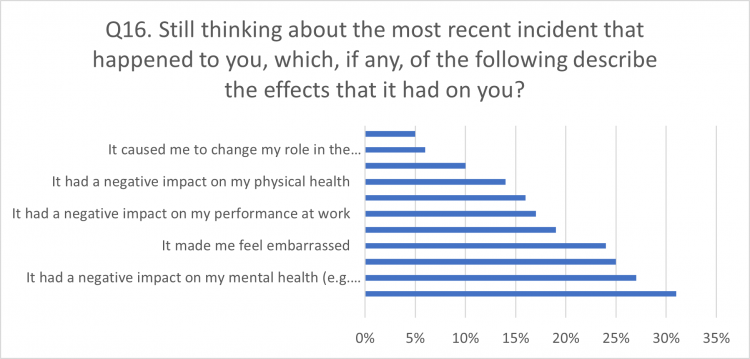

The combined impact of racism and sexism at work has a profound impact on BME women, taking a toll on their mental and physical health. It negatively impacts BME women’s confidence at work, their physical and mental health, and can cause women to leave their jobs. Higher numbers of BME women than men report taking sick leave or leaving their job because of discrimination.[6] Women are significantly more likely to say unfair treatment impacted their mental health, 29 per cent of women compared to under a quarter of men (24 per cent).[7]

Reporting incidents of racism and sexism

Speaking out about racism and sexism at work can come at tremendous personal cost to BME women. 74 per cent of BME workers feel uncomfortable raising issues with their manager compared to 66 per cent of their white colleagues.[1]

In our survey of BME women, one in three (34 per cent) told a partner, friends or family about an incident of bullying and harassment or unfair treatment. Just under a quarter told a colleague (24 per cent), 16 per cent told their employer and one in 14 sought help from a trade union rep. 27 per cent didn’t tell anyone.

BME women told us they didn’t report incidents to their employer because:

- 22 per cent thought their complaint would not be taken seriously

- One in five thought there would be no action taken

- One in six thought it could make the situation worse

Women were also worried reporting could damage their relationships with colleagues, that they may be viewed as a troublemaker or that they had reported incidents previously but no action had been taken.

BME disabled women were more likely to say they worried about the impact on their relationships with colleagues, 21 per cent compared to 10 per cent of BME non-disabled women. They were also more likely to say they had previously reported incidents but no action had been taken, around one in seven BME disabled women compared one in 20 BME non-disabled women.

Variations were less noticeable by age, although women aged 25 to 35 were more worried about the impact on their relationships with colleagues. Women in lower paid roles were more likely to think their employer would not take the issue seriously compared to those in medium to high paid roles.

Women employed on agency contracts were the most likely to think an employer would not take the issue seriously, 39 per cent compared to 21 per cent of permanently employed workers. Agency workers and those on zero-hours contracts were also much more likely to say they didn’t know who to report the incident to, 28 per cent and 23 per cent, compared to 10 per cent of permanently employed workers.

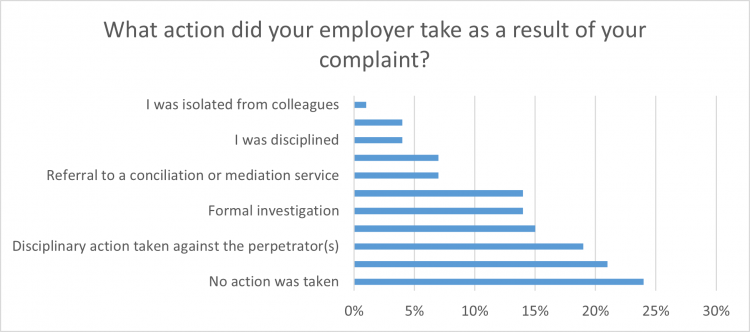

These fears are borne out in the evidence of action taken by employers when BME women did report. 67 per cent of women employed on agency contracts said their employer had taken no action to address their complaint. In contrast, in just under a quarter of cases (24 per cent) no action was taken on average across all BME female workers. Only in one in five cases was any preventative action taken by the employer after a report was made.

Part-time workers were also much less likely to be very satisfied with the action taken by their employer. 6 per cent of part-time workers said they were very satisfied compared to 22 per cent of full-time workers.

Intersecting inequalities

The combination of sexist and racist treatment that BME women face can be compounded by other discrimination they experience.

- Sexuality: One in eight BME LBT+ women have been seriously sexually assaulted or raped at work[1]

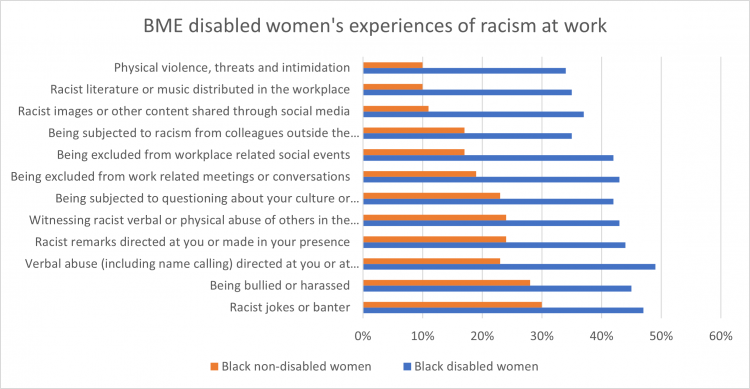

- Disability: Almost half of all disabled BME women (49 per cent) have been subjected to verbal abuse at work

- Age: Over half of young BME women (56 per cent) said they had been given harder or more difficult tasks than their peers compared to 31 per cent of BME female workers aged 35 and over

Across nearly every measure, BME disabled women reported higher levels of racism and abuse at work, compared to BME non-disabled women. They reported lower levels of satisfaction with how complaints were dealt with at work and were more worried about the impact of reporting racist incidents on their relationships with colleagues.

BME disabled women also reported significantly higher levels of unfair and discriminatory treatment:

- One in two (51 per cent) said they had had requests for training or development opportunities turned down compared to a quarter of non-disabled BME women (25 per cent)

- Close to half of disabled BME women (49 per cent) said they had not been given sufficient hours at work compared to one in five non-disabled BME women (20 per cent)

- 38 per cent had been singled out for redundancy compared to 19 per cent of non-disabled BME women

As these results show, anything that aims to tackle gender or racial equality at work has to take a truly intersectional approach. We must understand how institutional, and individual, power and privilege are utilised to exclude or discriminate against different groups of working women. To fail to do so, would render the most disadvantaged the most invisible. As Kimberle Crenshaw, who coined the term intersectionality, says “intersectionality is not just about identities but about the institutions that use identity to exclude and privilege. The better we understand how identities and power work together from one context to another, the less likely our movements for change are to fracture.”[1]

Conclusion

Institutionalised, structural racism and sexism is shaping the experience of BME women at work. BME women are at disproportionate risk of experiencing the triple impact of underemployment, low pay and job insecurity. This is putting their economic security and financial wellbeing at risk.

Across the labour market and in work BME women experience life changing disadvantage and racism. As the survey results show BME women with intersecting identities, particularly BME disabled women, face significant levels of discriminatory treatment in the workplace because of racial and sex-based stereotyping and prejudice. The cumulative impact has a profound impact on BME women’s economic security, their mental health and wellbeing.

The TUC and our affiliates have continually highlighted the barriers facing BME women in employment. Whilst welcoming the positive changes that have led to more access for BME women in the labour market and initiatives from trade unions to identify and tackle the problems that they face, much more needs to be done.

The effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the government’s response to it, have intensified the inequalities that BME women face at work, in our homes and in wider society. Wider systemic issues need to be resolved and this scale of change cannot be driven by individual employers alone.

Numerous reports – some commissioned by the government itself - that have called on successive governments to act to tackle entrenched, structural racism and sexism. If these recommendations had been acted on, BME workers would perhaps not have suffered the disproportionate number of deaths during this crisis.

Action is needed urgently now and it must be led by those workers who experience structural and individual racism and sexism at work on a daily basis. The TUC will therefore engage with BME women trade unionists who have been at the forefront of the fight to transform toxic workplaces and end structural inequalities to design effective solutions that must be implemented with urgency.

[1] Clare Wenham, Julia Smith, Sara E. Davies, Huiyun Feng, Karen A. Grépin, Sophie Harman, Asha Herten-Crabb and Rosemary Morgan (2020) Women are most affected by pandemics — lessons from past outbreaks, Nature, Vol 583, 9 July 2020

[2] TUC (2020) 2 in 5 working mums face childcare crisis when new term starts; TUC (2020) Forced Out: The cost of getting childcare wrong available at https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/forced-out-cost-getting-childcare-wrong

[3] Bandiera, O. et al. The Economic Lives of Young Women in the Time of Ebola: Lessons from an Empowerment Programme (Working Paper F-39301-SLE-2) (International Growth Centre, 2018).

[4] Insecure work: The total number in ‘insecure work’ includes (1) agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed – term contracts, (2) workers whose primary job is a zero-hours contract, (3) self-employed workers who are paid less than the National Living Wage (£8.72). Data on temporary workers and zero-hour workers is taken from the Labour Force Survey (Q4 2019). Double counting has been excluded. Low-paid self-employment: The minimum wage for adults over 25 is currently £8.72 and is also known as the National Living Wage. The number of working people aged 25 and over earning below £8.72 is 1,810,000 from a total of 3,950,000 self-employed workers in the UK. The figures come from analysis of data for 2018/19 (the most recent available) in the Family Resources Survey and were commissioned by the TUC from Landman Economics. The Family Resources Survey suggests that fewer people are self-employed than other data sources, including the Labour Force Survey

[5] TUC (2020) Dying on the job: Risk and racism

[6] BritainThinks conducted an online survey of 2,133 workers in England and Wales between 31st July - 5th August 2020. All respondents were either in work, on furlough, or recently made redundant. Survey data has been weighted to be representative of the working population in England and Wales by age, gender, socioeconomic grade, working hours and security of work in line with ONS Labour Force survey data

[7] Source: TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

[8] TUC + ICM Poll, February 2020

[9] TUC (2020) Dying on the job: Risk and racism

[10] Runnymede Trust; Womens Budget Group (2017) Intersecting inequalities: The impact of austerity on BME and minority ethnic women

[11] Citizens Advice, (2020) Citizens Advice reveal nearly 1.4 million people have No Recourse to Public Funds https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/about-us/how-citizens-advice-works/media/press-releases/citizens-advice-reveals-nearly-14m-have-no-access-to-welfare-safety-net/

[12] Pay in Working Class Jobs, TUC. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/payworking-class-jobs?page=3

[13] Ethnicity Pay Gaps in Great Britain, ONS. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/ethnicitypaygapsingreatbritain/2019

[14] TUC (2020) Government must introduce pay gap reporting now https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/government-must-introduce-ethnicity-pay-gap-reporting-now-says-tuc

[15] Guardian (2020) Pay Gap between ethnic minority and white staff smallest since 2012, available at https://www.theguardian.com/money/2020/oct/12/pay-gap-ethnic-minority-white-workers-ons

[16] TUC (2019) Disability employment and pay gaps: 2019

[17] TUC (2016) Living On The Edge

[18] Low-paid selfemployment: The minimum wage for adults over 25 is currently £8.72 and is also known as the National Living Wage. The number of working people aged 25 and over earning below £8.72 is 1,810,000 from a total of 3,950,000 self-employed workers in the UK. The figures come from analysis of data for 2018/19 (the most recent available) in the Family Resources Survey and were commissioned by the TUC from Landman Economics

[19] McGregor-Smith, R (2017) Race in the workplace: The McGregor-Smith Review

[20] BITC (2020) Race in the workplace

[21] Fawcett Society (2020) Sex and Power Index 2020

[22] Fawcett Society (2020) Sex and Power Index 2020

[23] NUT; Runnymede Trust (2017) Visible and invisible barriers: Pay and progression of BME teachers’

[24] TUC + Britain Thinks (2020)

[25] TUC (2017) Racism is real

[26] TUC + ICM survey (2020)

[27] TUC + Britain Thinks (2020)

[28] BITC (2020) BME employees have more ambition than white colleagues but are held back https://www.bitc.org.uk/news/BME-employees-have-more-ambition-than-their-colleagues-but-are-still-held-back-at-work/

[29] “

[30] TUC (2016) BME workers with degrees earn quarter less than white counterparts https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/BME-workers-degrees-earn-quarter-less-white-counterparts-finds-tuc

[31] Women’s Budget Group (2020) BAME women and Covid-19

[32] ONS, June 2020, Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by ethnic group, England and Wales: 2 March 2020 to 15 May 2020 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronaviruscovid19relateddeathsbyethnicgroupenglandandwales/

2march2020to15may2020#ethnic-group-breakdown-of-covid-19-deaths-by-age-and-sex

[33] “BME Workers Far more Likely to be Trapped in Insecure Work”, TUC: https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/bme-workers-far-more-likely-be-trapped-inse…

[34] The TUC based this calculation on how many workers across the economy want more hours in their existing jobs as well as the regularly published measure of the number of workers in part-time jobs who want to work full-time.

[35] TUC analysis of Q1 and Q2 2020 labour force survey - The LFS asks respondents both whether they are working part-time and would like full-time work, and whether they would like to undertake more hours in their current job. To control for double counting our underemployment total includes all of those who would like more hours in their current job, along with all those who are working part-time and would like full-time job but tell LFS researchers that they would not like additional hours in their current post

[36]

[37] TUC + ICM Poll (2020)

[38] ONS (2020) Employment in the UK https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/employmentintheuk/may2020

[39] TUC (2019) Racism Ruins Lives

[40] TUC (2019) Racism Ruins Lives

[41] TUC + ICM Poll (2020)

[42] TUC (2016) Still just a bit of banter?

[43] TUC (2017) Racism at work

[44] TUC (2006) Black women and employment

[45] EOC (2007) Moving On Up https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo…

[46] Runnymede Trust (2017) Islamophobia: Still A Challenge For Us All

[47] TUC (2017) Racism at work available at https://hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/institutes/code/research/projects/racism-at-work/tuc-full-report.pdf

[48] TUC + Britain Thinks (2020)

[49] TUC + Britain Thinks (2020)

[50] TUC (2019) Sexual harassment of LGBT+ workers

[51] Crenshaw (2019) Why Intersectionality Can’t Wait https://www.gwi-boell.de/en/2019/05/20/why-intersectionality-cant-wait

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox