A better normal

At long last a new normal is emerging in workplaces across the UK, as the vaccine programme provides greater protection against the threat of coronavirus. As we enter this new stage of transition from pandemic to endemic, the country is crying out for leadership and a practical plan to ensure that Britain at work is safe, secure and supported. We urgently need investment to boost economic growth that benefits every nation and region, and deliver fair shares and opportunities.

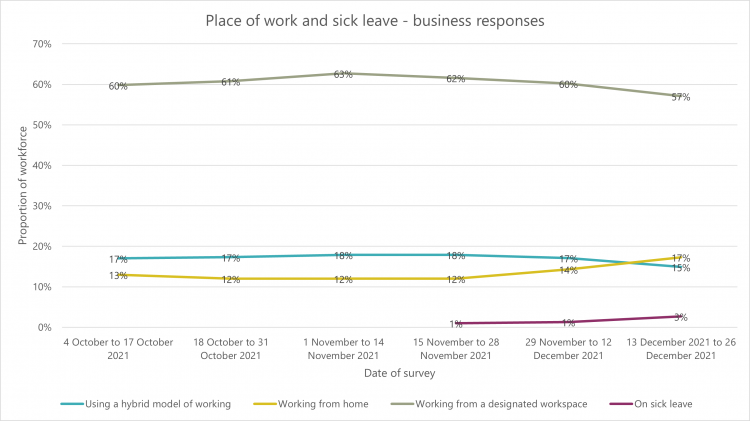

The government announced that Plan B restrictions will be lifted from the 24th of January, allowing for a greater return to normal life. Even before this latest announcement, when the requirement to ‘work from home if you can’ was in place, the latest data shows that between the 13th and 26th December, nearly 60 per cent of people were already working from their ‘normal’ workspace, with 15 per cent following a hybrid model, and 17 per cent working from home – significantly up on pre-pandemic levels.

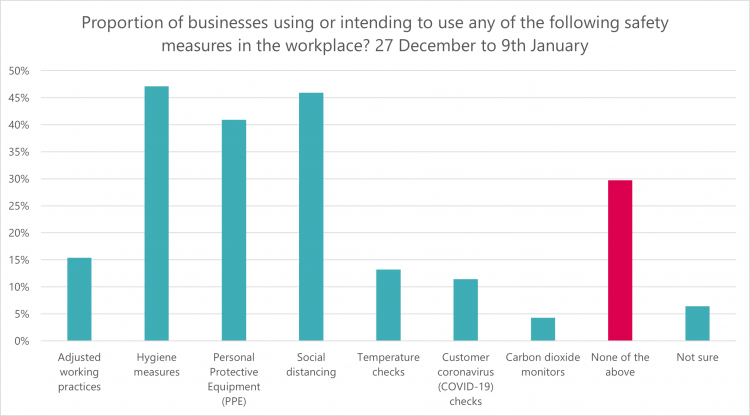

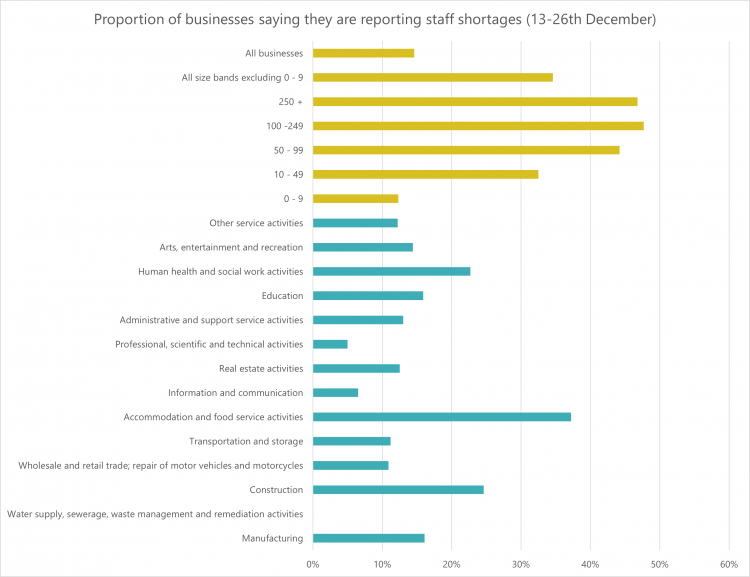

But this new normal has exposed new problems. Fifteen per cent of businesses, and almost half of large businesses, are facing staff shortages, while workers continue to endure another pay squeeze, holding back the economic recovery we need. The failure to enshrine the success of the furlough scheme means that workers and businesses have no protection against potential difficulties over the transition period and face constant uncertainty. Public services face huge backlogs at a time when vacancy and sickness rates are high, and many staff are simply exhausted. Unequal access to hybrid and flexible working is entrenching new inequalities. And too many workplace environments remain unsafe, with almost a third of businesses reporting they have taken none of the most protective actions to reduce the impact of Covid. The continued failure to fix our sick pay system leaves workers still facing impossible choices between helping to stop workplace outbreaks and facing severe financial hardship.

These problems are not an inevitable consequence of the virus, but the result of government policy and planning failures, including the false economy of austerity and the high cost of letting inequality soar. Yet in the last two years we have learned a lot about how we can live and work with the virus, while minimising its impact on lives and livelihoods.

Thanks to the NHS, the successful vaccine programme has given us an opportunity to build back better in 2022, delivering the ambition of a high wage, high productivity economy, and the ability to enjoy our lives without fear. But government must seize and shape this opportunity, working with unions and businesses to deliver safe and decent work for everyone in 2022.

This report sets outs a plan to do that – to ensure that the new normal is a better and fairer one. It recommends that government should:

1. Bring unions and business together in a ‘working better’ taskforce to set out a clear plan for how to address skills and workforce shortages, and deliver the Government’s stated ambition for a high wage high productivity economy.

2. Embed fair flexibility with a plan to ensure that everyone has access to fair flexible working arrangements, wherever they work.

3. Build public sector resilience through investment in the public sector workforce – ensuring that public services can recover, address backlogs and cope with the pressure that any new variants will place on them.

4. Bolster workplace safety and mental health support so that everyone can work with confidence

5. Boost workers’ financial security, providing protection against any new variants by fixing sick pay, increasing Universal Credit and putting in place a permanent short-time working scheme to provide certainty; and

6. Banish global vaccine inequality – ending the shameful vaccine inequality that is helping to contribute to the development of new variants.

The latest data, from the ONS ‘Business Insights and Conditions Survey’ for the 13th to 26th December, shows that around 60 per cent of the workforce were working from their normal place of work.

While there was an uptick in homeworking following the ‘work from home’ order applying from the 13th December, this was relatively small, with only an additional three per cent of the workforce working from home.

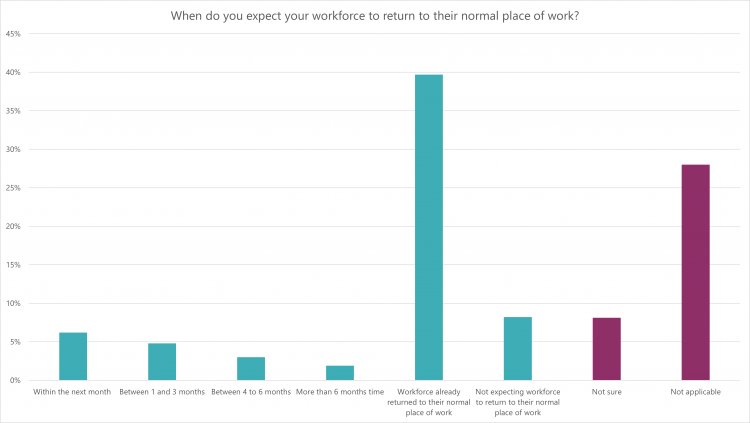

Most businesses who have had workers not in their normal place of work during the pandemic have now seen those workers return – with 40 per cent of businesses saying that workers have done so (and around 30 per cent saying that the question is not relevant).

A significant proportion of businesses say they intend to use increased homeworking in the future – 17 per cent, although 38 per cent do not, and 30 per cent say the question is not applicable . But there is some evidence that working patterns may have stabilised.

However, this ‘new normal’ has brought with it new problems. As the chart above shows, Omicron drove a high level of sickness absence in December, with around three per cent of all workers off sick – the highest since June 2020. Due to the failures of the sick pay system, we estimate that around a quarter of a million workers were self-isolating during this period with no or inadequate sick pay.1

High levels of staff sickness may be related to the failure of many businesses to take action to improve workplace safety. Thirty per cent of businesses say they have taken none of a range of common measures – including social distancing – to improve safety at work.

- 1 TUC (17 January 2022) ‘TUC: Cutting self-isolation period won’t fix UK’s fundamental sick pay problem’ at https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/tuc-cutting-self-isolation-period-wont-fix-uks-fundamental-sick-pay-problem

Many businesses also report a shortage of skills. In September, A third of the companies that responded to the CBI’s July manufacturing survey were concerned that skills shortages would limit output, and half of consumer services firms said that labour shortages would limit investment in the year ahead – the highest figures since the 1970s.2

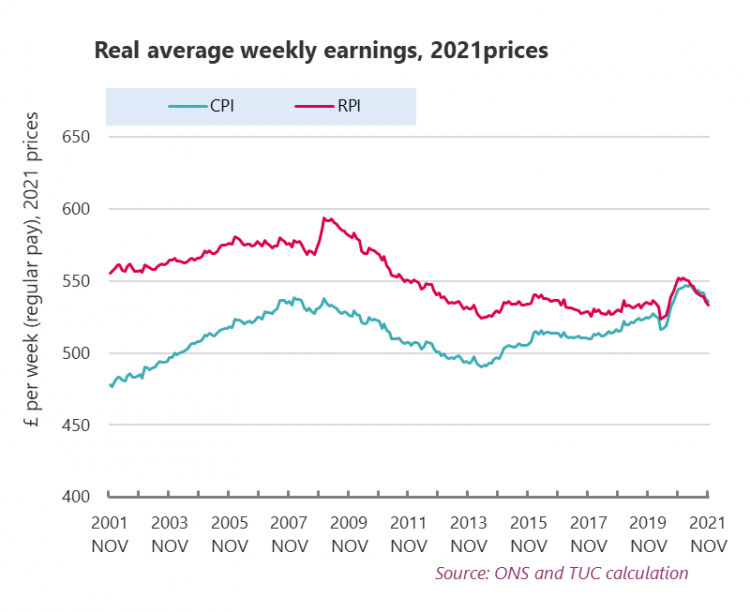

However, outside of some areas where unions are able to deliver significant increases, these conditions are not delivering sustained pay rises for workers. The latest labour market figures show that real pay is now £3 a week below its 2008 peak.

- 2 CBI (September 2021) A perfect storm, CBI insights on labour market shortages and what to do about it at https://www.cbi.org.uk/media/7159/20210906-a-perfect-storm-cbi-latest-labour-market-insights.pdf

Staff absences are just one element of a wider problem of staff shortages. 15 per cent of all businesses, and almost half of large businesses say that they are facing staff shortages, with particular issues in hospitality, health and construction.

The issues faced by workers and businesses are not an inevitable consequence of covid, but a failure of government policy to plan and react to changing conditions. This report sets out the steps government should take now to shape the new normal into one that delivers for workers.

When the pandemic hit, unions and business worked together to help deliver a package of economic support through the furlough scheme that protected millions of jobs. It was notable that Rishi Sunak thanked both the TUC and CBI in his speech announcing the job retention scheme – and stood with Frances O’Grady and Carolyn Fairbairn when he announced that support would continue in November 2020.

The labour market now faces different challenges, with skills and labour shortages providing significant disruption to business operations. Of those businesses reporting labour shortages, over 10 per cent said they had had to pause trading either some (9.7 per cent) or all (3 per cent of their business) in December. Many of these shortages -notably in logistics – are in sectors where unions have been reporting poor working conditions for years, and asking for these to be addressed to aid recruitment and retention. Workers remain trapped in a more than decade long wage squeeze, despite pockets of pay-rises,

Addressing these challenges, and achieving the Government’s stated ambition of a ‘high wage, high productivity’ economy, requires bringing together those with expertise in what’s really going on in the world of work. The government should convene a ‘working better’ taskforce to advise on how to achieve the mission of a high wage, high productivity economy. The taskforce should:

- Be chaired by a Cabinet Level Minister;

- Be modelled on the Low Pay Commission, bringing together three worker representatives, three business representatives, and two independent experts. The worker and businesses representatives should include the heads of the TUC and CBI;

- Meet three times, reporting before the financial statement in the autumn, on;

- A plan to ensure that workers and businesses have the skills they need to succeed in the post covid economy;

- A plan to ensure a ‘race to the top’ on labour standards and productivity; and

- Recommendations for how to achieve the Government’s stated ambition of a high wage economy.

- A plan to ensure that workers and businesses have the skills they need to succeed in the post covid economy;

The pandemic has re-focused attention on flexible working, with work from home requirements – for those who can -a key part of the measures put in place to control the spread of the virus. But debates about the extent to which homeworking will continue for office workers must not obscure the wider questions about how to embed fair flexibility for everyone – including those who cannot work from home, roughly half of the workforce. Without action to embed flexibility for everyone, we risk widening inequalities between workers; but with the right policies in place we can ensure flexibility works for everyone.

Broadening the debate about flexible working

Genuine flexible working can be a win-win arrangement for both workers and employers. It can allow people to balance their work and home lives, is important in promoting equality at work and can lead to improved recruitment and retention of workers for employers.

There is a real appetite among workers for a range of flexible working options. TUC research shows more than four out of five (82 per cent) workers in Britain want to work flexibly in the future, rising to 87 per cent amongst women workers. The most popular forms of flexible working desired in the future are remote working, flexi-time, and part-time work but workers would also like job sharing, annualised hours, term time only working, compressed hours and mutually-agreed predictable hours to be made available to them.

But at present, access to these forms of work is deeply unequal. Too many people in working-class occupations are closed out of genuine flexibility and instead have worse terms and conditions masquerading as ‘flexibility’ forced onto them in the form of zero-hours contracts and other forms of insecurity. This so-called ‘flexibility’ strips workers of rights and makes them face irregular hours and therefore irregular income. Work is offered at the whim of their employer and last-minute shift changes are the norm.

When workers try and access genuine, two-way flexibility, for example flexi-time, remote working and part-time work, figures from before the pandemic show that three in ten of their requests for flexible working are turned down, with employers having an almost unfettered ability to do so, given the breadth of the statutory “business reasons” that can currently be used to justify a refusal 3

. The most popular form of flexibility, flexi-time is unavailable to over half (58 per cent) of the UK workforce. This number rises to nearly two-thirds (64 per cent) for people in working-class occupations.4

.

The experience of the pandemic has significantly changed the landscape of flexible working. In March 2020, and in subsequent waves of restrictions, all those who could work from home were required to do so. This has brought about a popular narrative of home working being the common experience of the pandemic. But this is far from being the case. Those who have worked from home are more likely to be in higher paid occupations and from London and the Southeast5

. However, over half of the workforce continued to work outside the home. These workers have not been able to access the flexibility available to home workers. With the exception of home working, all forms of flexible working fell between 2020 and 2021, meaning that has been even harder than before for these workers to access flexible working arrangements.6

.

As we exit the pandemic there is a real risk of a class and geographical divide being created between the flexible working haves and have nots. A recent survey of employers suggests that employers are more likely to not offer flexible work to staff who could not work from home during the pandemic. One in six (16 per cent) of employers surveyed said that after the pandemic, they will not offer flexible working opportunities to staff who could not work from home during the pandemic. This compares to one in sixteen (6 per cent) saying they will not offer flexible working opportunities to those who did work from home in the pandemic 7

..

Embedding fair flexibility

Demand for remote working has been transformed by the experiences of enforced home working during the pandemic. More than nine out of ten (91 per cent) of those who worked from home during the pandemic want to spend at least some of the time working remotely, with only one in 25 (4 per cent) preferring to work from an external workplace full time. Access to home-based working is particularly important for disabled workers who highlighted a range of benefits including reduced fatigue and greater control of working hours 8

., and working mothers, the majority of whom said that without flexible working arrangements it would be difficult or impossible to do their job 9

.

We cannot allow flexible working to become a perk for the favoured few - offered to a minority of the workforce who are able to work from home – and serving to reinforce existing inequalities.

As well as ensuring that there is fair access to flexible working, we need to make sure that flexible working benefits workers, helping them balance their work and home lives. Future flexibility must provide predictability, including regular shift patterns and notice of hours to address the damaging impacts of insecure work.

We need to ensure that as businesses respond to this demand, new flexibilities are implemented fairly, and address the challenges as well as opportunities of this form of work. Steps need to be taken to ensure that, after the pandemic, the experience of those working from home does not mirror the damaging one sided ‘flexibility’ experienced by so many on zero-hours contracts, with arrangements imposed that only benefit employers. Increased access to remote working must not come at the price of reductions to workers pay, increased intrusive remote surveillance, unsafe working environments, lack of access to union representatives, an increase in unpaid hours worked and draining, always-on cultures. No worker should denied the ability to return to working from an external workplace and be forced to work from home as the result of money saving office closures.

We believe trade unions are best placed to work with employers to ensure competing demands are reconciled and workers needs met. These include responding to the organisational challenges that new forms of flexibility can impose, including responding to production cycles and public demand for services. Trade unions have long experience of negotiating collective solutions to these problems that balance workers’ and business needs.

Recommendations

- The government must set out a strategy on the future of flexible work and its integral role in shaping a better and more equal recovery for workers following the pandemic. This should include how they aim to respond to the impacts that increased remote working may have on transport, retail, hospitality and other sectors potentially affected by decreased office working in city centres. Increased levels of remote working could have substantial adverse effects for other workers in these sectors. The government’s strategy must include steps to ensure that the jobs of those who may be impacted by lower levels of office-based working are not threatened.

- There is widespread recognition of the fact that the current legislative framework in relation to flexible working wasn’t working effectively before the pandemic. The government itself has highlighted the need for change in its 2019 manifesto commitment to make flexible working the default. We need the government to act without delay to introduce their long-promised Employment Bill and strengthen workers' rights in a range of areas to make sure we have a system of genuine flexible working that works for all workers.

- This must include a right for workers to disconnect from work to have communication free time in their lives, a duty on employers to consider which flexible working arrangements are available in a role and publish these in job advertisements and a day one right to flexible working.

- 3 TUC (2019) Transparency: Flexible working and family related leave and pay policies at https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-10/BEISFlexibleworking.pdf

- 4 TUC (2019) Transparency: Flexible working and family related leave and pay policies at https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-10/BEISFlexibleworking.pdf

- 5 ONS (2021) Homeworking hours, rewards and opportunities in the UK: 2011 to 2020 at https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/labourproductivity/articles/homeworkinghoursrewardsandopportunitiesintheuk2011to2020/2021-04-19#characteristics-and-location-of-homeworkers

- 6 CIPD (2021) Flexible working arrangements and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic at https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/relations/flexible-working/flexible-working-impact-covid

- 7 See TUC (2021) The future of flexible work at https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/future-flexible-work

- 8 See TUC (2021) Disabled workers’ access to flexible working as a reasonable adjustment at https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-10/DisabledWorkersFlexibleworking2_0.pdf

- 9 See TUC (2021) Denied and discriminated against: the reality of flexible working for working mums at www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-10/Report.pdf

The experience of the Covid-19 pandemic confirmed the safety and security of our society relies on strong and resilient public services, and on our public sector workers who have worked tirelessly to keep essential services going during the crisis.

The pandemic exposed the damage that a decade of austerity inflicted on our public services, which went into the crisis weakened by years of funding cuts, real-terms cuts in pay and with no effective workforce strategy in key areas like health and social care, leaving services understaffed and stretched to the limit. These cracks were compounded by years of marketisation and outsourcing that undermined accountability, created unequitable access to service provision, and put workers and communities in harm’s way during the pandemic.

This crisis must mark a turning point. To ensure our public services are robust enough to carry us through this pandemic, and withstand the challenges of any future ones, our public services require a sustained period of investment that reverse a decade of cuts and ensure we have a stable and decently paid workforce able to deliver the services our country relies on.

Reversing a decade of lost pay for public sector workers

From frontline healthcare workers and public health officials, to teachers and school support staff, refuse collectors, care workers, bus drivers and transport workers, civil servants and those in local government, our key workers in the public sector have been at the frontline of responding to the pandemic.

However, after a decade of government-imposed pay restraint, many of these workers earn less today than they did in 2010, by up to £3,500 a year in some cases.

In November 2020, the Chancellor announced a public sector pause for 2021/22 that covered most of the major public sector workforces from teachers and the police to prison officers, civil servants and the judiciary.10

The below-inflation 2021 pay rises awarded in local government and the NHS also represented a pay cut in real terms. TUC research found one in five key workers faced financial difficulty during the pandemic, with many turning to foodbanks, debt or a second job to get by.11

While the Chancellor formally ended the public sector pay freeze in his comprehensive spending review of 2021, spiralling inflation and lack of early, significant pay rises for public sector workers, means many continue to be at the sharp end of the cost-of-living crisis.

Government can take immediate action to restore the public sector’s resilience by restoring the pay of our valued public sector workforce. Ending the pay squeeze on public sector workers is essential not only out of fairness to public servants but also to address the growing recruitment and retention crisis across the public sector. Public sector pay awards in 2022 and beyond should meet the cost of living, protecting the living standards of working families, including those in outsourced role - as well as moving towards restoring lost earnings over the last 11 years of Conservative rule. This should be reflected in government submissions to the independent Pay Review Bodies as well as its own pay remit for central government departments.

Address the staffing crisis to clear the backlog

Tackling the backlog in public services, most notably in health, is rightly a key priority for the government. By doing so, we can begin to restore balance and stability to the sector and shore up its resilience. But the government’s decision to hold down public sector workers pay has undermined these efforts, intensifying the staffing crisis facing key areas such as health, social care, education and justice. Areas where backlogs and access issues are most acute.

Across the public sector, unfilled vacancies put a huge strain on remaining staff, leading to burnout, sickness-related absence and high turnover.

In social care, 1.6 million older adults do not receive the support and care they need with essential living activities such as bathing, eating and getting dressed.12

This figure is likely to be the tip of the iceberg, with friends and family stepping in to plug the gap in social care provision. Before and during the pandemic, the sector has approximately 122,000 vacancies and a turnover rate of 30.4 per cent.13

In justice, the pandemic exacerbated a pre-existing backlog of cases waiting to be tried in the criminal courts systems. The backlog has had significant impacts on defendants, some of whom are being held in custody on remand, and on victims and witnesses, some of whom have been denied for justice, waiting for months and years for even extremely serious cases to be heard.14

In the NHS, the backlog has reached record breaking proportions. Of the 5.8 million patients waiting to start treatment in September 2021, 300,000 have been waiting more than a year15

and 12,000 more than two years.16

In September 2021, NHS England was operating short of almost 100,000 staff due to unfilled vacancies. These shortages were exacerbated by high staff absences related to the Omicron wave during Winter 2021.

While the government have indicated tackling the NHS backlog is a priority, investing revenue raised from a new increase in national insurance contributions, the health system’s ability to do this will be undermined without additional investment and planning to tackle the recruitment and retention crisis facing the NHS.

As noted by the House of Commons Health and Social Care Select Committee, the government are effectively flying blind in their bid to clear the NHS backlog, without any independent workforce projections, ministers have idea of whether “enough doctors, nurses or care staff are being trained”.17

The same applies to other areas of the public sector workforce.

To build the public sector’s resilience, we need a fully funded, long-term public sector workforce strategy, developed with unions and employers. This must include measures to maintain and improve upon current staffing levels, with a focus on job creation in key growth areas such as social care, and annual reporting on staffing levels. Without this, our public services will struggle to meet the daily challenge of responding to the current pandemic, let alone begin to tackle the massive challenge of clearing the backlog or readying themselves to meet any future crises.

Any workforce strategy must be backed up by a new public sector funding settlement that reverses a decade of sustained cuts. This must include increased funding for non-ring-fenced areas such as the justice sector, whose 2019/2020 budget was 25 per cent lower than in 2010-2011.18

Recommendations

- Government should fund sustained increases in pay for public sector workers that restore what they have lost through ten years of cuts and slow growth.

- Government must set out a long-term public sector workforce strategy with a focus on job creation, union engagement and an immediate end to any planned cuts to civil service headcount and any other public sector departments.

- Government must deliver a new funding settlement for our public services that, as a minimum, reverses the last decade of sustained cuts and ensures services can clear the Covid-19 backlog.

- 10 HMT (2020) Spending Review 2020 documents - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- 11 TUC (2021) TUC poll: 1 in 5 key workers say they've cut back on spending during pandemic | TUC

- 12 Age UK (2021) Care in Crisis | Age UK

- 13 Skills for Care (2020) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England (skillsforcare.org.uk)

- 14 House of Commons (2021) Reducing the backlog in criminal courts - Committees - UK Parliament

- 15 NHS England, NHS referral to treatment (RTT) waiting times data September 2021, 11 November 2021 (Patients referred for non-emergency consultant-led treatment are on RTT pathways. An RTT pathway is the length of time that a patient waited from referral to start of treatment, or, if they have not yet started treatment, the length of time that a patient has waited so far)

- 16 Nuffield Trust, NHS performance summary: September-October 2021, 11 November 2021

- 17 House of Commons (2022) Clearing the backlog caused by the pandemic (parliament.uk)

- 18 House of Commons Library briefing, ‘The spending of the Ministry of Justice’, 1 October 2019, at p. 2

Protecting workers from Covid transmission protects our health, economy and the NHS: it’s in all our interest. It requires a commitment from the government to invest in necessary resources, and to compel employers to implement protections.

We know Covid is an airborne virus, meaning it is primarily spread through breathing in tiny particles in the air. It has thus far taken agencies and employers too long to catch up on the science and adjust worker protections accordingly – away from droplet spread toward aerosol spread prevention.

We must prepare for future pandemics, meaning long-term investment now to protect workers in the future. It’s in employer and workers’ interests: a safer workplace will see fewer absences. Long-term investment in occupational safety and health will not only reduce Covid transmission but will also help reduce the risk of other occupational hazards, too.

Risk assessments: engage the workforce

There is a legal obligation to assess and manage all risks in a workplace – and to consult with unions and/or the workforce on this process. Employers have a statutory responsibility to protect the health and well-being of their employees at work. Assessing employees’ risk is an ongoing process and must be updated in the face of evidence of new or developing risks, as often as required. For example, following evidence of changing exposure or of alternative control measures. This should be done in consultation with workers and representatives.

Risk reduction should follow the hierarchy of controls model: elimination, substitution, controls. Employers begin by eliminating the possibility of transmission by allowing people to work from home; and where this cannot be done, alter the job role so it can be done in a safer environment; then adjust the environment so it is suitably ventilated, socially distanced and so on. Personal Protective Equipment is a last resort control measure, as it is the least effective, protecting a worker only once they are in an environment where it is likely they will breathe in Covid aerosols. Employers must ‘layer’ control measures to ensure the greatest level of risk reduction and worker protection.

Unions must be engaged in the risk assessment process. Trade unions and employers must agree on how risks are managed: consulting with the workforce in the risk assessment process is key to its success. Employers should consult employees, unions, and health and safety representatives to assess workplace hazards and outline steps for mitigation in carrying out a risk assessment. There are approximately 120,000 trained union health and safety reps in workplaces across the UK. This number should be mobilised to help ensure that workplaces are safe, including workplaces with no existing union reps and unions are not recognised. Union health and safety reps should be given the opportunity to negotiate a ‘roving role’ to enter workplaces where no union is recognised to ensure compliance.

Once agreed, risk assessments and action plans must be sent or otherwise effectively communicated to the whole workforce. Workers know best how their jobs can be adapted to accommodate risk controls, and union safety reps are typically more highly trained in health and safety than their managers. An engaged and informed workforce is much more able to adhere to safety measures. Regular health and safety meetings must continue to occur. This may also mean union reps need more time and facilities to allow effective communication with their members. Risk assessments should be made publicly available, too: the government should introduce new rules to compel employers to publish workplace-wide risk assessments.

Unions must be able to continue supporting workers: employers must not unreasonably withhold access to a premises as long as the trade union gives sufficient notice.

The Government has advised employers to publish their risk assessments – the TUC wants to see this made a legal requirement to offer transparency and confidence to workers and customers, enabling them to check Covid-secure compliance.

Covid testing: keep it free

Covid testing is crucial in helping identify and remove cases from a workplace, and therefore keeping workers safe and sickness absences low. Unions have welcomed the introduction of testing in many workplaces and recognise the necessity for long-term testing.

Access to testing must be expanded. Proposals to begin charging workers for testing are flawed. Many workers will have difficulty affording tests, and this will inevitably increase the number of circulating infections. Access to rapid testing should remain free, with priority to key workers in jobs where regular contact with the public is required.

Workers testing positive must be supported to self-isolate as required, with adequate sick pay (see Section 2). Voluntary testing schemes must not be used as a means of financial penalising workers.

The government should continue collecting and publishing the number of Covid-19 positive cases, including those reported on lateral flow devices. Understanding where Covid outbreaks are identified can help to inform where additional control measures may be required.

Face masks: improve the standard

To prevent transmission among workers who come into regular contact with the public, or where aerosol protections are inadequate, there must be a greater emphasis on effective mask-wearing. While any form of face covering helps prevent transmission to an extent, the variation is stark: studies show the wearing of a surgical face mask has a 74% higher risk rate of transmission compared with FFP2/3 standard face masks worn correctly19

..

Britain is behind other countries in Europe in its recommendation of the use of FFP3-grade masks. For example, in some countries, respirator masks are required on public transport and in shops. Even in healthcare in England, the use of FFP3 remains limited to a small group of workers dealing directly with Covid-19 patients. This must be rectified, with clear guidance issued to workers and employers on the scientific benefits of mask-wearing compared with face coverings. Highly transmissive virus variants require more effective equipment: FFP2/3-grade respirator masks must be worn in more environments.

Ventilation: a legal requirement

Good ventilation, where we ensure the air is renewed and refreshed regularly, is key to reducing Covid transmission risk. Every workplace risk assessment must include aerosol transmission, and outline what steps are being taken to improve ventilation where necessary. Airborne protection is the most effective means of protecting the largest number of people from Covid transmission. The government must rapidly introduce measures to help clean the air in workplaces, including grants to allow public services and businesses to upgrade ventilation system where necessary.

Employers can immediately be using CO2 monitors to measure fresh air supply in indoor workplaces, and in cases where ventilation is poor, install air filtration units, upper room UV disinfectant and/or other protections which are easy to obtain. This must be done at scale.

The TUC supports proposals for a simple method of communicating airborne risk level, which would help reassure workers and the public, and hold employers accountable for managing risk. The Independent SAGE proposal ‘Scores on the Doors’20

.would indicate the measures in place to prevent aerosol spread in a given indoor space with an accessible graphic.

Social distancing

The airborne nature of Covid means workers keeping a distance from others remains an effective control measure. Employers should consider establishing maximum occupancy where possible, and in particular where job roles allow for remote working.

Without significant changes to travel patterns, it is not possible for social distancing measures to be in place on public transport, especially at peak times. As part of its plan for a mass return to work outside the home, the Government must provide guidance for employers, commuters and transport providers on what measures are needed to safeguard public health. Employers should be encouraged to offer flexible work options, and allow for workers to stagger shift times to avoid overcrowding on public transport.

Workers at increased risk

Certain sections of the population have been identified as being at additional risk of developing serious complications from Covid. These include those receiving immunosuppressive therapy known to make vaccines less effective. Employers should be undertaking risk assessments on an individual basis for any employee with a heightened vulnerability to Covid – this should be subject to enforcement.

Pregnancy can also suppress the immune system and so extra precautions must be taken to protect pregnant workers. Pregnant workers and new mothers have explicit additional protections in under the Management of Health and Safety at Work regulations, including a right to regular risk assessments. Employers must try to remove or prevent exposure to risks, and if not possible, offer suitable alternative employment at the same rate of pay if available. If pregnant workers cannot work because of health and safety risks, the law stipulates they should be suspended on full pay.

As of December 2021, 1.3 million people in Britain have Long Covid, according to ONS data21

.. The groups most likely to report having Long Covid are people aged 35 to 69 years, women, disabled people, those living in more deprived areas and workers in health care, social care, or teaching and education. Common symptoms of Long Covid include fatigue, shortness of breath and difficulty concentrating. Coercing workers back into work despite health concerns could risk worsening their health, as well as putting others at risk of accident and/or injury. Workers who experience lasting effects of Covid must be supported in any return to the workplace, based on medical advice. Referrals to occupational health services will be key to understanding individual’s needs, abilities and how symptoms may affect a job role.

The TUC supports a call for universal access to Occupational Health services for all workers. We also wish to see Long Covid automatically classified as a disability for the purposes of the Equality Act 2010, and in certain sectors where there is an evidenced high correlation between job role and Covid infection, as an occupational illness. These classifications would help protect workers from discrimination, give them a right to reasonable adjustments at work and support those for whom a safety-critical role may no longer be viable because of their Covid-19 infection.

Regulation and Enforcement

Keeping workplaces safe must not rely on employer willingness alone – active and effective enforcement is key to ensuring compliance. The TUC wishes to see tougher enforcement action and more pro-active inspections in sectors where the number of Covid outbreaks remains high. The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) must act quickly to apply sanctions to employers that do not risk assess for Covid-19 or fail to provide safe working arrangements. These are legal duties, and failing to meet them amounts to criminal breach, not just technical failings. While advice might work with the willing, it is no deterrent to bad employers: the HSE needs to take action – including prosecutions – against employers who do not take safety seriously.

Regulations which mandate employers to consult with unions and worker representatives must also be enforced. The TUC believes more serious safety breaches could be avoided if more employers were made to fulfil their duty of engaging the workforce in the risk assessment process.

The government and regulator should run a public information campaign to ensure workers know their rights, and employers their responsibilities. To support this, the HSE and local authority regulators who inspect workplaces need additional, long-term funding and resources.

The HSE and local authorities (the other primary workplace safety regulator) have suffered enormous funding cuts in the last ten years. In 2009/10, the HSE received £231 million from the Government, and in 2019/20, it received just £123 million: a reduction of 54% in ten years. Less funding means fewer inspections: over the same ten-year period, the number fell by 70%, and over a twenty-year period, the number of prosecutions has fallen by 91%. The Government's £14million fixed-term grant to HSE has not increased the number of inspectors. Instead, most of these funds have gone to contractors who are unwarranted, lacking a right of entry to workplaces or any enforcement powers, and they do not have the specialist health and safety knowledge of trained HSE inspectors. Long-term, adequate funding of safety regulation is required if we keep workplaces safe and ensure employers who break the rules face the necessary consequences.

Recommendations

- Risk assessments: Employers must be compelled to provide airborne protections for workers, with ventilation measures and FFP3-grade face masks. Individual risk assessments must be completed for groups of workers at heightened risk. Publication of workplace-wide risk assessments should be made a legal requirement. And publication of risk assessments must be made mandatory.

- Regulation and Enforcement: Tougher enforcement is required to incentivise robust risk management, and government must provide a new funding settlement to HSE and local authorities allowing them to invest in inspectorate capacity.

- Covid testing: expand access to rapid testing, keeping it free, with prioritisation for frontline ‘key’ workers.

- 19 See https://www.pnas.org/content/118/49/e2110117118

- 20 See https://www.independentsage.org/covid-scores-on-the-doors-an-approach-to-ventilation-fresh-air-information-communication-and-certification/

- 21 See https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/6january2022

The covid pandemic has shown the need for stronger safety nets to protect workers – and businesses – against unexpected events, including the need for either national lockdowns, or individual self-isolation. The government’s response to national lockdowns, in the form of the furlough scheme, was one of the stand out successes of the pandemic response. We should learn from its success, putting in place a permanent short-time working scheme.

But almost two years into the pandemic, it is a source of national shame that the government has not fixed the UK’s exceptionally poor sick pay provision. Strengthening this vital safety net must be part of a new and better normal in the year ahead. And government must help families facing a cost of living crisis after a decade of social security cuts, by increasing Universal Credit.

Providing job security through a new short-time working scheme

The measures set out in this report should help to keep workplaces open, and limit the need for wider restrictions, including those which sharply reduce demand, or require businesses to close. But when these restrictions are required their impact would be significantly minimised if workers and businesses could rely on predictable support being in place to protect jobs. That’s why the TUC called in August 2021 for a new, permanent, short-time work scheme to be put in place to provide workers and businesses with certainty in the face of future challenges.

Building on the success of furlough

The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (JRS), and accompanying Self Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS), were introduced at speed in March 2020, following discussions with unions and business. While far from perfect, the schemes have been recognised as one of the successes of the government’s response to the pandemic, with the CJRS – or furlough scheme - supporting 11.6 million people and playing a clear role in limiting job losses.

The UK had to start its furlough scheme from scratch when the pandemic hit. But schemes supporting temporary lay-offs or short-time work are common in most developed economies. Twenty-three countries in the OECD had short-time working schemes in place before the coronavirus pandemic, including most famously Germany, but also Japan and many US states. These schemes have many benefits, including protecting jobs, income and skills, preventing the widening of inequalities as those most affected by structural discrimination lose their jobs first, saving employers on recruitment costs, and helping to stabilise the economy by supporting consumer spending.

A permanent scheme with predictable criteria for access would help ensure these benefits were realised in any future restrictions, lowering the cost of restrictions to both workers and businesses. Evidence from across Europe suggests that short-time working schemes are cost effective. Research for the European Commission concluded that: “Expenditure for STW schemes has not been a significant financial burden in the past, except in crisis years in countries where short-time work is heavily used. Moreover, expenditure for these measures is not additional but an alternative to payments for unemployment benefits that would have otherwise been incurred.”[1] The aim of a permanent short-time working scheme would not be to embed its use for long periods, but to provide a safety net for workers and employers when health (or other conditions) make restrictions essential.

Design considerations for a new short-time work scheme

The TUC believes that the eventual criteria for accessing a new permanent short-time work scheme should be defined by a tripartite panel bringing together unions, business and government, building on the success of social partnership in working in developing the furlough scheme. These criteria could include:

- Employers should be able to demonstrate a temporary reduction in demand -for example, a ten per cent reduction in turnover or working hours.

Most European schemes require companies to demonstrate a temporary reduction in demand, with some schemes setting a numerical threshold (a table setting out criteria across European schemes is in the TUC’s longer report on short time work schemes, published in August 2021).[2] Companies could be asked to submit an application setting out their evidence for the reduction in demand, which could be later be confirmed against tax receipts (in much the same way that individuals file self-assessment tax returns, which they can later correct).

In order to demonstrate that reductions in demand are temporary, some schemes (in Austria, the Czech republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden) required employers to demonstrate that they were not in a situation of insolvency or bankruptcy or that they had met all their social insurance and tax obligations or both.

One way of assessing viability could be to require employers to make a continuing contribution towards the cost of employment, but we recommend that this is capped at the level of national insurance and pension contributions to maximise the flexibility of the scheme. The scheme should also remain open to parents and carers who need to use it to deal with the impact of health measures on caring responsibilities.

The panel set up to design the scheme should also consider how better support could be provided to self-employed people, learning from the experience of the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme.

- Firms seeking to access a short-time working scheme should show that they have come to an agreement with their workers, either through a recognised union or through consultation mechanisms.

Most short time work schemes across Europe have a requirement to negotiate the scheme with employees, with, for example, firms in Germany required to show that they have agreed the use and duration of the scheme with Works Councils. Firms should be required to do the same thing in the UK – coming to agreement with a recognised trade union, or through formal collective consultation with their staff, using similar processes to those required when firms are making multiple redundancies.

This requirement provides a valuable safeguard against misuse of the scheme by employers. As use of the scheme will normally involve some loss of income by workers, they are unlikely to agree to it unless there is no other alternative.

- The scheme should ensure full flexibility in working hours

The flexibility embedded in the furlough scheme has enabled companies to bring workers back gradually, to adapt their working conditions, and enable work sharing. This flexibility should be embedded in the design of any new scheme, allowing workers to work any proportion of their normal working hours, including zero.

- Workers should continue to receive at least 80 per cent of their wages for any time on the scheme, with a guarantee that no-one will fall below the minimum wage for their normal working hours

Workers should continue to receive at least 80 per cent of their wages for hours during which they are accessing the scheme, with a cap on the maximum amount that can be paid to limit the support to high earners.

However, the flaw in the current scheme that allows workers to fall below the minimum wage for their normal working hours should be fixed, with all workers guaranteed that their wages will not fall below the minimum wage for the hours they normally work.

- Any worker working less than a specified proportion of their normal working hours must be offered funded training.

A missed opportunity within the furlough scheme was that workers did not have the chance to use non-working time to improve their skills. A permanent scheme, particularly one designed to help deal with periods of industrial change, should invest significantly more in training.

One option would be for employers who have furloughed workers who are working less than a proportion of their normal working hours to be required to offer workers independent advice on the training and development that will futureproof their skills, and to help facilitate participation in identified training. We suggest that this criteria is drawn widely to enable as many workers to participate in training as possible. Additionally, the government could meet the national insurance and pensions costs of firms that provide appropriate training to furloughed staff.

Access to other free retraining courses that will support progression and job prospects - such as level 2 qualifications and ICT/digital courses – should also be available at no cost for furloughed workers. And the government should consider how workers on furlough could be supported to take up higher level qualifications in sectors identified as expanding.

- There should be time limits on the use of the scheme, with extension possible in limited circumstances

To encourage businesses to only use the scheme in exceptional circumstances, it might be sensible to place a time limit on any single use of the scheme. We suggest that this could be set at an initial six-month period with extension possible in exceptional circumstances – such as the covid crisis itself. This should allow firms facing a shortfall in demand, or needing a period to transition to new ways of doing business, to hold onto valuable staff.

- Firms accessing the scheme should be required to set out a plan for fair pay and decent jobs

Access to a short-time working scheme should be used as an opportunity for firms to get back on their feet – and to rethink how they operate. This should include a plan to offer fair pay and decent jobs to their staff – agreed with unions, and respecting the terms of any collective agreement already in place.

At a minimum, firms wishing to access the scheme could be asked to set out within three months a plan agreed with unions or staff to:

- Ensure that no staff within the company are paid less than the living wage

- Reduce pay ratios within the company to a maximum of 20:1

- Eliminate the use of zero hours and insecure contracts within their business; and

- Allow trade unions access to their workplace where there is no collective agreement in place.

These conditions should cover all workers directly or indirectly employed by the business, including any outsourced, agency, or contracted workers.

- Firms accessing the scheme should commit to paying their corporation tax in the UK, and not pay out dividends while using the scheme.

A short-time work scheme should be designed to protect jobs when businesses have no other option, not to protect company profits. Firms using the scheme should not pay dividends while doing so, and must pay their fair share when they can, by committing to pay their corporation tax in the UK.

- The scheme should be designed to promote equality, and monitored on its success in doing so

The ability to access the furlough scheme for working parents and workers who need to ‘shield’ from the coronavirus because of a pre-existing health condition has been an important step to considering how short-time work schemes can help prevent structural inequalities from widening during times of crisis. Government should ensure that, in line with their public sector equality duty, they take account of equality as an integral part of drawing up a future scheme. This is best done through an equality impact assessment. Regular monitoring should also be carried out on the outcomes of the scheme for different groups.

Fixing sick pay

In contrast to the success of the furlough scheme, the failure to fix the sick pay system is a national disgrace that has held back our pandemic response.

When the scale of the pandemic became apparent in March 2020, the TUC called for three reforms.

- Day one provision of statutory sick pay, abolishing the three waiting days required to claim the benefit;

- Including an additional two million people within the sick pay scheme, by removing the ‘lower earnings limit’ that excludes those on low pay; and

- Raising the level of sick pay to the level of the real living wage.

To date, the government has only responded to the first of these, providing day one access to sick pay in cases of coronavirus in March 2020. Efforts to work safely throughout the pandemic will continue to be frustrated until the other two reforms are implemented.

Including an additional two million people in sick pay

The ‘lower earnings limit’ excludes those who do not earn more than £120 a week from access to statutory sick pay. TUC analysis shows that this means that around two million working people do not have access to any sick pay when asked to self-isolate – currently for a period of ten days. This particularly hits women, and those in insecure work.[3] In polling undertaken in May 2021 for the TUC, around half of those on insecure contracts said that they would receive no sick pay when off work.[4]

Self-isolation when infectious is a critical tool to prevent the spread of the virus. But research has consistently shown that a lack of financial support is a barrier to self-isolation. For example, research published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) found that “Those with lowest household income were three times less likely to be able to work from home and less likely to be able to self-isolate”.[5]

Fixing this exclusion would be a straightforward step for government to take. In fact, government had consulted on removing the lower earnings limit in November 2019, before the pandemic hit.[6] The response to the consultation found strong support for this measure, stating that “A majority of respondents (75%) agreed that SSP should be extended to employees earning below the LEL. This measure was supported by small and large employer respondents alike. Respondents felt that by extending SSP to those earning below the LEL, employers would be better incentivised to reduce sickness absence for all of their employees.”[7] However, government decided to u-turn on its previous promise, stating, incomprehensibly, that “now is not the right time to introduce changes to the sick pay system.”

Instead, government have introduced the temporary self-isolation payment scheme. The scheme is intending to provide a £500 payment to workers on low incomes who have been required to self-isolate due to Covid-19. To be eligible, workers must be unable to work from home and will lose income due to self-isolating. This scheme is not a success. TUC research found only one-in-five workers (21 per cent) even know about the scheme. Awareness drops even further among groups who most need the support: low-paid workers (16 per cent), those in insecure work (18 per cent), and those who receive no sick pay (16 per cent). Even when they have heard of it, few workers qualify; freedom of information requests sent by the TUC in May 2021 found that 64 per cent of applicants to the scheme were being rejected.[8]

TUC commissioned analysis by the Fabian Society found the cost of removing the lower earnings limit would be around £150m a year.[9] This could either be met by employers, or by the government as part of an extension of the temporary rebate paid to smaller employers facing sick pay costs (this rebate was extended as part of a December 2021 package of support for businesses). There is no excuse for failing to put in place this vital protection for low paid workers.

Raising the rate of sick pay to the level of the real living wage

Even when people do access statutory sick pay, the rate is so low that it can push workers into hardship. At £96.35, the rate is now at its lowest level in real terms (that is, taking account of the cost of living), since March 2003, almost nineteen years ago. High inflation, and the government’s refusal to uplift the benefit rate, mean that even compared to the beginning of the pandemic in February 2020, sick pay is now worth £3 less a week.[10] Polling for the TUC found that two-fifths of workers say they would have to go into debt, or go into arrears on their bills, if their income dropped to the level of statutory sick pay (which was £95.85 when the polling was undertaken in 2020).[11]

The rate of sick pay in the UK also compares very poorly to that received by workers in other countries. Statutory sick pay in the UK is worth around 16 per cent of average weekly earnings, compared to an average payment in OECD countries of over 60 per cent.[12] And while some employers top up statutory sick pay with occupational pay, many do not. A BritainThinks survey, carried out on behalf of the TUC, found that almost a quarter (of workers receive only basic SSP if they are off work sick. This equates to around 6.4 million employees. The less someone earns, the less likely they are to receive full sick pay. While 35 per cent of those earning less than £15,000 per year receive full pay when sick, compared to 87 per cent of those earning over £50,000 per year.[13]

Most employers, as well as workers, support an increase in the rate of Statutory Sick Pay. A report published by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) in December 2021 found that “nearly two thirds (62%) of employers agree that the SSP rate is too low and should be increased”.[14]

Increasing the rate of statutory sick pay to the level of the real living wage would cost around £110 per employee per year, for those employers not already paying occupational sick pay.[15] Again, government could help meet those costs through retaining the sick pay rebate for small business. And this would be a small price to pay for ensuring that workers who need to self-isolate can do so without facing a choice between putting their colleagues at risk and not being able to pay their bills.

Boost Universal Credit

The UK safety net is failing as a result of years of deliberate attacks on the social security system, with around £34 billion of cuts made to social security since 2010.[16] Families facing rising energy bills this April have had their ability to cope dramatically reduced by these cuts – and the temporary £20 boost to Universal Credit from September this year: the Resolution Foundation estimate that “the number of households suffering from ‘fuel stress’ – spending at least 10 per cent of their family budgets on energy bills – is set to treble overnight to 6.3 million households when the new energy price cap comes into effect on April 1st”.[17]

Rather than temporary fixes, we need a real boost to social security. The TUC believes that Universal Credit is not fit for purpose, and should be scrapped and replaced. But families needing help now cannot wait – and government should immediately raise the level of Universal Credit to £270 a week, around 80 per cent of the level of the real Living Wage.

Recommendations

- The government should bring together unions and business to start work on the design of a new permanent short-time working scheme.

- Government should ensure that all workers can access sick pay by immediately removing the lower earnings limit to access statutory sick pay.

- Government should raise the level of statutory sick pay to the level of the real Living Wage, (around £320 a week).

- Government must raise the rate of Universal Credit to 80 per cent of the level of the real living wage, around £270 a week.

[1] European Commission, European Network of Public Employment Services, (2020) Short time work schemes in the EU Study report European Commission – short time work schemes in the EU see https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=22758&langId=en

[2] TUC (2021) Beyond furlough: why the UK needs a permanent short-time work scheme at https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/beyond-furlough-why-uk-needs-permanent-short-time-work-scheme

[3] TUC (2021) Sick pay that works at https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/sick-pay-works

[4] See TUC (2021) Self-isolation payments: the failing scheme barely anyone’s heard of at https://www.tuc.org.uk/blogs/self-isolation-support-payments-failing-scheme-barely-anyones-heard

[5] Atchison C, Bowman LR, Vrinten C, et alEarly perceptions and behavioural responses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of UK adultsBMJ Open 2021;11:e043577. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043577

[6] In the consultation document ‘Health is everyone’s business’ published in 2019, the government stated that: “The government proposes to reform SSP so that it is better enforced and more flexible in supporting employees. This includes amending the rules to enable an employee returning from a period of sickness absence to have a flexible, phased return to work. It also includes extending protection to those earning less than the Lower Earnings Limit (LEL) (currently £118 per week) who do not currently qualify for SSP, as recommended in the Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices.” See HM Gov (2019) Health is everyone’s business at https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/health-is-everyones-business-proposals-to-reduce-ill-health-related-job-loss/health-is-everyones-business-proposals-to-reduce-ill-health-related-job-loss

[7] HM Government (2021) Government response: health is everyone’s business at https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/health-is-everyones-business-proposals-to-reduce-ill-health-related-job-loss/outcome/government-response-health-is-everyones-business

[8] See TUC (2021) Self-isolation payments: the failing scheme barely anyone’s heard of at https://www.tuc.org.uk/blogs/self-isolation-support-payments-failing-scheme-barely-anyones-heard

[9] Andrew Harrop (2021) Statutory sick pay: options for reform Fabian Society, available at https://fabians.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/SSPreport.pdf

[10] TUC (2021) UK workers face worst real-terms sick pay in nearly two decades as Covid-19 cases surge - new TUC analysis at https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/uk-workers-face-worst-real-terms-sick-pay-nearly-two-decades-covid-19-cases-surge-new-tuc

[11] TUC (2020 Sick pay and debt at https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/sick-pay-and-debt

[12] OECD (2020) Paid sick leave to protect income, health and jobs through the COVID-19 crisis see figure 3, at https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/paid-sick-leave-to-protect-income-health-and-jobs-through-the-covid-19-crisis-a9e1a154/

[13] TUC (2021) Sick pay that works at https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/sick-pay-works

[14] CIPD (14th December 2021) Almost two thirds of employers say the UK’s Statutory Sick Pay rate is too low and should be increased, according to CIPD research at https://www.cipd.co.uk/about/media/press/141221statutory-sick-pay-low#gref

[15] Andrew Harrop (2021) Statutory sick pay: options for reform Fabian Society, available at https://fabians.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/SSPreport.pdf

[16] See TUC (July 2021) Universal credit cut will hit millions of working families and key workers https://www.tuc.org.uk/blogs/universal-credit-cut-will-hit-millions-working-families-and-key-workers

[17] Resolution Foundation (January 2022) Families suffering from ‘fuel stress’ set to treble overnight to six million households as energy bills soar at https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/press-releases/families-suffering-from-fuel-stress-set-to-treble-overnight-to-six-million-households-as-energy-bills-soar/

Equitable and free access to vaccines is vital to tackling the coronavirus pandemic, preventing new variants emerging and protecting us all, yet Global South countries have only been able to access a fraction of the number of vaccines that Global North countries have been able to. 72 per cent of shots that have gone into arms worldwide have been administered in high- and upper-middle-income countries. Only 0.9 per cent of doses have been administered in low-income countries. 39

The World Health Organisation reports that while 67 per cent of the population in high income countries have received at least one shot of the vaccine, only 10.56 per cent of the population in low income countries have received at least one shot. This is due to the high cost of purchasing patented vaccines.40

As a consequence the pandemic is having a catastrophic effect on the health and livelihoods of Global South societies, deepening global inequalities. Meanwhile, low rates of vaccinations enabled the Omicron variant to develop – the WHO has warned further mutations of the virus are likely if large populations remain unvaccinated.41

The World Trade Organisation’s Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property rights - or TRIPs - rules prevent Global South countries from locally producing low-cost versions of patented Covid vaccines. A waiver to these rules has been proposed by South Africa and India which would enable countries to produce affordable versions of patented Covid vaccines. This waiver would allow Global South countries to provide their populations with the vaccines they critically need, as well as enable countries to produce low-cost Covid tests, medical treatments, Personal Protective Equipment products and other vital public health tools. The development of these vaccines was funded overwhelmingly by public money, and their use should be viewed as a public good.

Shamefully the UK government is one of the few countries globally to be blocking a waiver to TRIPs rules. Over 100 governments now support a waiver to the TRIPs rules including the US, Australia and New Zealand.

The TUC urges the government to use the UK's influence to reduce global inequalities and promote public health worldwide by supporting the waiver to TRIPs rules proposed by South Africa and India.

- 39 The New York Times (2022) ‘Tracking Coronavirus vaccinations around the world’, available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/world/covid-vaccinations-tracker.html

- 40 UNDP (2022) ‘Vaccine Access’, available at: https://data.undp.org/vaccine-equity/accessibility/

- 41 World Health Organisation (WHO), ‘Interim statement on booster doses of Covid-19 vaccine’, available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/22-12-2021-interim-statement-on-booster-doses-for-covid-19-vaccination---update-22-december-2021

List of recommendations

Bring unions and business together in a ‘working better’ taskforce to set out a clear plan for how to address skills and workforce shortages, and deliver the Government’s stated ambition for a high wage high productivity economy.

Embed fair flexibility with a plan to ensure that everyone has access to fair flexible working arrangements, wherever they work.

- The government must set out a strategy on the future of flexible work and its integral role in shaping a better and more equal recovery for workers following the pandemic. This should include how they aim to respond to the impacts that increased remote working may have on transport, retail, hospitality and other sectors potentially affected by decreased office working in city centres. Increased levels of remote working could have substantial adverse effects for other workers in these sectors. The government’s strategy must include steps to ensure that the jobs of those who may be impacted by lower levels of office-based working are not threatened.

- There is widespread recognition of the fact that the current legislative framework in relation to flexible working wasn’t working effectively before the pandemic. The government itself has highlighted the need for change in its 2019 manifesto commitment to make flexible working the default. We need the government to act without delay to introduce their long-promised Employment Bill and strengthen workers' rights in a range of areas to make sure we have a system of genuine flexible working that works for all workers.

- This must include a right for workers to disconnect from work to have communication free time in their lives, a duty on employers to consider which flexible working arrangements are available in a role and publish these in job advertisements and a day one right to flexible working.

Build public sector resilience through investment in the public sector workforce – ensuring that public services can recover, address backlogs and cope with the pressure that any new variants will place on them.

- Government should fund sustained increases in pay for public sector workers that restore what they have lost through ten years of cuts and slow growth.

- Government must set out a long-term public sector workforce strategy with a focus on job creation, union engagement and an immediate end to any planned cuts to civil service headcount and any other public sector departments.

- Government must deliver a new funding settlement for our public services that, as a minimum, reverses the last decade of sustained cuts and ensures services can clear the Covid-19 backlog.

Bolster workplace safety and mental health support so that everyone can work with confidence

- Risk assessments: Employers must be compelled to provide airborne protections for workers, with ventilation measures and FFP3-grade face masks. individual risk assessments must be completed for groups of workers at heightened risk. And publication of risk assessments must be made mandatory.

- Regulation and Enforcement: Tougher enforcement is required to incentivise robust risk management, and government must provide a new funding settlement to HSE and local authorities allowing them to invest in inspectorate capacity.

- Covid testing: expand access to rapid testing, keeping it free, with prioritisation for frontline ‘key’ workers.

Boost workers’ financial security, providing protection against any new variants by fixing sick pay, increasing Universal Credit and putting in place a permanent short-time working scheme to provide certainty;

- The government should bring together unions and business to start work on the design of a new permanent short-time working scheme.

- Government should ensure that all workers can access sick pay by immediately removing the lower earnings limit to access statutory sick pay.

- Government should raise the level of statutory sick pay to the level of the real Living Wage, (around £320 a week).

- Government must raise the rate of Universal Credit to 80 per cent of the level of the real living wage, around £270 a week.

Banish global vaccine inequality – ending the shameful vaccine inequality that is helping to contribute to the development of new variants.

- The government should support the waiver to World Trade Organisation intellectual property (TRIPs) rules proposed by South Africa and India to ensure Global South countries can produce low cost versions of the vaccine. This is needed to address the stark global inequalities in vaccination rates which have had a devastating impact on livelihoods in the Global South and increased the risk that further variants of Covid-19 develop.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox