Sick pay and debt

Expanding sick pay

We also want to see SSP expanded so that it’s available to all, not just those earning an average of £120 per week or more.

The government has introduced a pilot scheme for low-paid workers where it will pay £13 a day to employees or self-employed workers who are told to isolate because they have coronavirus, a household member has coronavirus, or they have been contacted by NHS Track and Trace after being in contact with someone with the virus. However, this will only apply in areas that are in a local lockdown. And to be eligible the applicant has to be unable to work from home and currently be receiving Universal Credit or Working Tax Credit.

This all means that the new scheme doesn’t pay enough, doesn’t reach enough people and doesn’t help those who have to get by on sick pay for other illnesses. That’s why we want to see a full extension of SSP to all workers, rather than temporary, insufficient schemes.

Wider support for struggling households

We also reiterate our calls for a more extensive package to support household finances. This should include a fully funded freeze on council tax debt repayment. Council tax debt collection is harsh, ineffective, inefficient and can push people further into debt. It also comes with the underlying threat of imprisonment[1].

The government should also:

- Significantly increase the hardship fund delivered by local authorities and establish a permanent fund that provides a source of grants to support those facing hardship.

- Explore ideas such as writing off council tax debt and providing the outstanding money to councils. As of the end of March 2020, the total amount of council tax still outstanding was £3.6 billion[2]. Writing this off but paying the outstanding amount to councils would have two benefits, providing both debt relief for struggling households and a significant cash injection to local councils.

- Increase the support it provides to renters, including an extension of the eviction ban that is set to end on 20 September.

It’s also important that we don’t let the job guarantee scheme come to a sudden end in October. The government should adopt the TUC’s proposal for a Jobs Protection and Upskilling Deal that would provide support for businesses that have brought back workers for a minimum amount of time, while ensuring workers are still receiving at least 80 per cent of their pay and the offer of training if working less than 50 per cent of their normal hours[3].

If you think sick pay should be higher, take action today and sign the petition below

The current level of sick pay at £95.85 a week is too low, and those forced to self-isolate could be pushed into debt. We need an increase in the level of statutory sick pay to the level of the real living wage, and for everyone to qualify for sick pay, no matter what they earn.

Many workers are already struggling with household finances due to the pandemic. A household debt crisis has been looming for the past few years, and without significant intervention, it could hit when a range of temporary support measures end later in the year.

This note sets out new findings on sick pay and debt from a largescale survey carried out by BritainThinks.

The problem with sick pay

Statutory sick pay (SSP) is currently £95.85 per week. This is around one-fifth (19%) of average weekly earnings (£504), meaning that being on SSP for just one week could cost the average employee over £400 in lost earnings. Self-isolating for two weeks on SSP would mean losing out on £816.

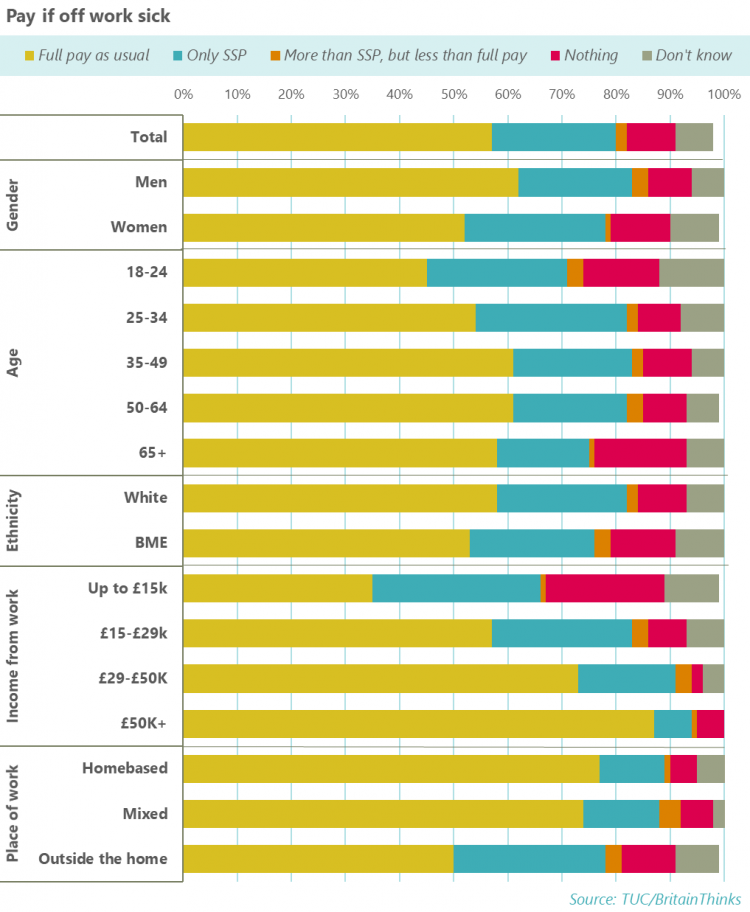

A BritainThinks survey, carried out on behalf of the TUC[1], found that almost a quarter (23%) of workers receive only basic SSP if they are off work sick. This equates to around 6.4 million employees. 57 per cent receive their usual pay in full, with 9 per cent telling us they receive nothing. A small percentage of workers receive more than SSP, but less than full pay.

These broad figures mask disparities. For example:

- 26 per cent of women receive only SSP, compared to 21 per cent of men. Male employees are also more likely than female employees to receive their full pay (62 per cent compared to 52 per cent), and less likely to receive nothing (8 per cent compared to 11 per cent)

- The less someone earns, the less likely they are to receive full sick pay. 35 per cent of those earning less than £15,000 per year receive full pay when sick, compared to 87 per cent of those earning over £50,000 per year

- While black and minority ethnic (BME) employees are as likely as white employees to receive only SSP, BME employees are more likely to receive no sick pay at all (12 per cent compared to 9 per cent) and less likely to receive full sick pay (53 per cent compared to 58 per cent)

- Young workers are more likely to receive only SSP, and young workers and older workers are most likely to receive no sick pay at all

- Those working from home are much more likely to receive full sick pay than those who are working outside the home (77 per cent compared to 50 per cent)

As the above shows, some workers miss out on SSP entirely. To be eligible for SSP, an employee must, on average, earn £120 per week. This is known as the lower earnings limit. Around 1.8 million employees will miss out on SSP due to this, with 7-in-10 of those who miss out being women. The lower earnings limit also particularly impacts young workers, older workers, those on zero-hours contracts, and certain occupations. The occupations where missing out on sick pay is most prevalent are low-paid occupations[2].

As well as this, self-employed workers are not eligible for SSP, meaning that around 5 million workers miss out for this reason[3].

The relationship between sick pay and debt

Those who receive only SSP, or receive no sick pay at all, will face a big hit to their income if they take time off sick. The average worker will see their weekly income fall from £504 to just under £96, an 80 per cent drop.

This is particularly an issue at the moment, as stopping the spread of coronavirus heavily relies upon people isolating when they have the virus. Current guidance says that those with coronavirus symptoms must self-isolate for ten days, and those who have been in contact with someone with symptoms must isolate for two weeks[4].

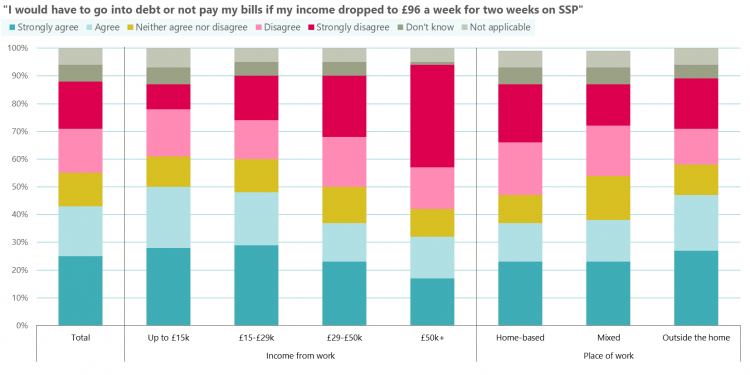

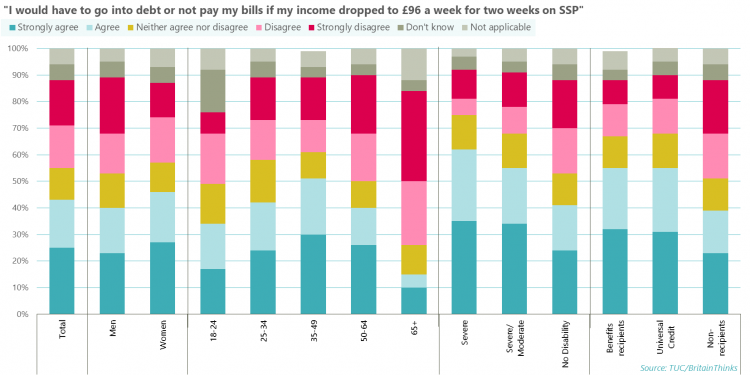

The current level of SSP, however, may discourage those with symptoms from self-isolating. Living off just SSP for two weeks will push many people into financial hardship. Over 4-in-10 workers (43 per cent) told us that they would have to go into debt or not pay bills if their income dropped down to £96 per week for two weeks.

Concerningly, those who have been working outside their home are more likely than those working from home to say they’d fall into debt or not pay bills if they had to live off SSP for two weeks (47 per cent compared to 37 per cent).

Those on low and average incomes are also more likely than high earners to be unable to cope on SSP without being pushed into debt. Half of those earning less than £15,000 per year and around half (47 per cent) of those earning between £15,000 and £29,000 say they’d be unable to get by without going into debt, compared to around a third (32 per cent) of those earning more than £50,000 per year.

Other groups of workers are more likely to fall into debt should they have to self-isolate on SSP for two weeks. These include disabled workers, middle aged workers and female workers.

The impact of the pandemic on household finances

Household debt was a problem before the pandemic hit. StepChange, the debt advice charity, has warned that problem debt was already prevalent in the UK. In 2019, the charity received a call every 49 seconds. In the same year, new clients had an average of £14,129 in unsecured debt. This has risen by 8 per cent across the past three years[5]. Data from The Insolvency Service shows that, in 2019, individual insolvencies hit their highest levels since 2010[6]. An insolvency occurs when someone is unable to keep up with debt repayments.

Trussell Trust, a network of food banks, showed there was a record high use of food banks in the 2019/20 financial year. 1.9 million emergency parcels were distributed, an 18 per cent increase on the previous year. This follows years of rapidly increasing food bank use, with a 74 per cent increase in the number of parcels distributed compared to four years ago[7]. The situation has worsened since the pandemic began, with an 89 per cent increase in food bank use in April 2020 compared to the same month in 2019. This means the first full month of the pandemic was the network’s busiest month on record[8].

StepChange has reported that demand for debt advice in June and July 2020 was lower than the same period in 2019. However, it notes that many of those with problem debt are currently being given respite by temporary measures such as payment holidays, the furlough scheme, the ban on evictions and the pausing of bailiff action[9]. However, these have now ended or are set to end over the next few weeks and months. Bailiff action for collecting council tax debt, for example, has already resumed[10], the furlough scheme ends completely at the end of October, and while the eviction ban had a last-minute four-week extension, it is now set to end on 20 September[11]. StepChange therefore warns that the coming months look “turbulent”.

This is a view shared by the Standard Life Foundation, who have referred to the period we’re in now as the calm before the storm. Its research shows that 3.7 million households have been granted a bill ‘payment holiday’, and that the majority of these already have financial difficulties and will struggle once the payment holiday ends. It explains that many households will be facing a double whammy as their payment holiday ends on the same date as the furlough scheme. Debt advice services will then face increased demand, with around1.6 million households potentially needing debt advice once existing support ends[12].

Research by Citizens Advice paints a similarly worrying picture[13]. It estimates that 6 million adults in the UK have fallen behind on bills due to the pandemic. This includes:

- 4 million on their mobile phone or broadband bills

- 3 million on their water bills

- 8 million on their energy bills

- 8 million on their council tax

- 2 million on their rent

Our survey findings provide further insight into the impact the pandemic has already had on the household finances of working people.

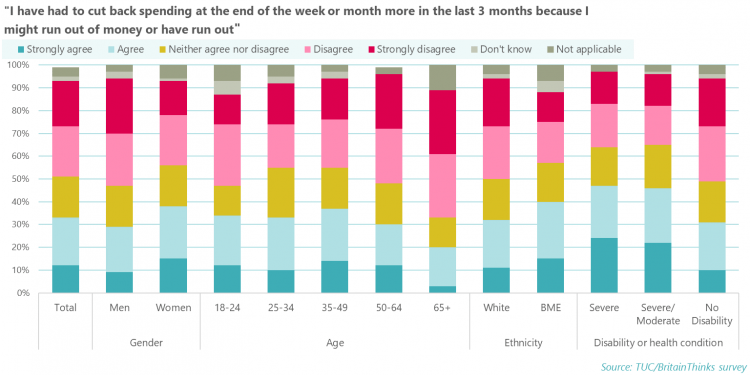

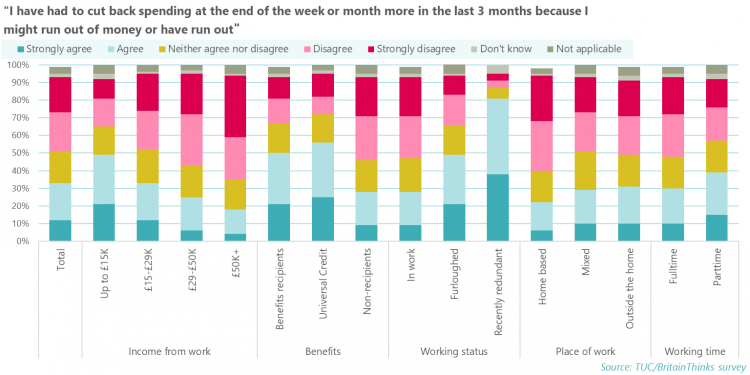

A third of workers (33 per cent) told us that they have had to cut back spending at the end of the week or month more in the last 3 months, either because they might run out of money or because they have run out.

Disabled workers, BME workers and female workers are all more likely to be cutting back on spending as a result of the pandemic.

There are also disparities by income and working patterns:

- Those on lower incomes are more likely to have had to cut back more than usual. Half (49 per cent) of those earning less than £15,000 per year have had to cut back, compared to 18 per cent of those earning above £50,000 per year

- Those who have been furloughed (48 per cent) and those who have recently been made redundant (81 per cent) are more likely than those still in work as normal (28 per cent) to be cutting back on spending due to the pandemic

- Workers who receive benefits are more likely than those who are not to have to cut back spending (50 per cent, compared to 28 per cent)

It’s also notable that while some agree that they are having to cut back more due to the pandemic, there’s plenty who disagree or strongly disagree with this. This dynamic of sharply different experiences of the pandemic was also present when we asked people about their levels of debt and disposable income since the pandemic began. While 22 per cent agreed that they’d reduced their debts since the beginning of the pandemic, 42 per cent disagreed, with 22 per cent strongly disagreeing. Those on low incomes (earning less than £15,000 per year) are less likely to say they’ve paid off debt (19 per cent, compared to around a quarter of average and higher earners). As are those who have been recently furloughed (16 per cent, compared to 22 per cent of those who haven’t been furloughed).

When it came to disposable income, one-fifth of workers (21 per cent) told us their disposable income has increased since the pandemic began, whereas half of workers (52%) disagreed with this. Those on low and average incomes and those who have been furloughed were more likely to disagree with the statement. Those working from home were more likely than those not working from home to agree that their disposable income has increased since the pandemic (29 per cent compared to 19 per cent).

This reflects a trend seen during the pandemic that while some are saving money due to the restraints on spending and money saved on commuting, others are struggling due to, for example, being on reduced wages or already low incomes.

The Bank of England, for example, has found that lower income households have been more likely to report a fall in savings as a result of the pandemic. Its analysis shows that households with an annual income of less than £20,000 have reported the largest fall in savings, while households with an annual income of more than £55,000 have reported the biggest increase[14]. This is a trend predicted by IPPR at the start of the pandemic, who argued that much of the response to the crisis is “likely to significantly exacerbate existing structural inequalities – insulating creditors and asset-owners from the worst effects of the pandemic while driving many of the most financially vulnerable deeper into debt”[15].

What we want to see change

Without action, it’s clear that the low rate of SSP could force those with symptoms, and those told to self-isolate, to choose between going into debt or going into work due to fear of facing financial hardship if they don’t.

We also need to address what is likely to become a household debt crisis. Many are already struggling to pay bills and finding themselves in debt. This could lead them to face repayments for years to come. On a wider scale, it may also dampen any future economic recovery. Any recovery will depend on people being able and feeling confident to spend. This is unlikely to be the case if people are burdened by debt repayments.

Increasing sick pay

A rise in statutory sick pay is needed so that those who must self-isolate can do some without being pushed into poverty and debt. We also want this to apply generally. With or without a pandemic happening, no one should face financial hardship just because they got ill.

We reiterate our calls for the weekly SSP rate to be raised to the equivalent of a week’s real living wage (£326 per week). This would guarantee that everyone who has to take time off work when sick would still at least be paid enough to live on.

Our survey shows that a rise in statutory sick pay (SSP) is clearly popular with workers.

When we asked workers to select their three top priorities for improving work, increasing the level of sick pay was the third highest priority, beaten only by raising the national minimum wage to £10 an hour and banning zero-hour contracts.

Expanding sick pay

We also want to see SSP expanded so that it’s available to all, not just those earning an average of £120 per week or more.

The government has introduced a pilot scheme for low-paid workers where it will pay £13 a day to employees or self-employed workers who are told to isolate because they have coronavirus, a household member has coronavirus, or they have been contacted by NHS Track and Trace after being in contact with someone with the virus. However, this will only apply in areas that are in a local lockdown. And to be eligible the applicant has to be unable to work from home and currently be receiving Universal Credit or Working Tax Credit.

This all means that the new scheme doesn’t pay enough, doesn’t reach enough people and doesn’t help those who have to get by on sick pay for other illnesses. That’s why we want to see a full extension of SSP to all workers, rather than temporary, insufficient schemes.

Wider support for struggling households

We also reiterate our calls for a more extensive package to support household finances. This should include a fully funded freeze on council tax debt repayment. Council tax debt collection is harsh, ineffective, inefficient and can push people further into debt. It also comes with the underlying threat of imprisonment[1].

The government should also:

- Significantly increase the hardship fund delivered by local authorities and establish a permanent fund that provides a source of grants to support those facing hardship.

- Explore ideas such as writing off council tax debt and providing the outstanding money to councils. As of the end of March 2020, the total amount of council tax still outstanding was £3.6 billion[2]. Writing this off but paying the outstanding amount to councils would have two benefits, providing both debt relief for struggling households and a significant cash injection to local councils.

- Increase the support it provides to renters, including an extension of the eviction ban that is set to end on 20 September.

It’s also important that we don’t let the job guarantee scheme come to a sudden end in October. The government should adopt the TUC’s proposal for a Jobs Protection and Upskilling Deal that would provide support for businesses that have brought back workers for a minimum amount of time, while ensuring workers are still receiving at least 80 per cent of their pay and the offer of training if working less than 50 per cent of their normal hours[3].

Fixing the social safety net

All of this must be done alongside fixing our broken social safety net. The benefit system needs an emergency overhaul to make it fit for purpose.

The social security system should support those who do lose their jobs to stay on their feet, and not face a damaging spiral into debt. Government must therefore:

- Raise the basic level of universal credit and legacy benefits, including jobs seekers allowance and employment and support allowance, to at least 80 per cent of the national living wage (£260 per week).

- End the five-week wait for first payment of universal credit by converting emergency payment loans to grants.

- Remove the savings rules in universal credit to allow more people to access it.

- Significantly increase child benefit payments and remove the two-child limit within universal credit and working tax credit.

- Ensure no-one loses out on any increases in social security by removing the arbitrary benefit cap. In addition, no one on legacy benefits should lose the protection of the managed transition to universal credit as part of this change.

- Scrap the no-recourse-to-public-funds rules that deny working families access to social security.

[1] BritainThinks conducted an online survey of 2,133 workers in England and Wales between 31st July - 5th August 2020. All respondents were either in work, on furlough, or recently made redundant. Survey data has been weighted to be representative of the working population in England and Wales by age, gender, socioeconomic grade, working hours and security of work in line with ONS Labour Force survey data.

[1] This is based on TUC analysis of Q2 2020 of the Labour Force Survey. It’s the number of employees who earn less than £120 per week.

[2] The latest Office of National Statistics labour market statistics for Apr-June 2020 show that there are around 4.8 million self-employed workers.

A01: Summary of labour market statistics, GOV.UK – ONS. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmen…

[3] Stay at home: guidance for households with possible or confirmed coronavirus (COVID-19) infection, GOV.UK – Public Health England. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-stay-at-home-guidance/stay-at-home-guidance-for-households-with-possible-coronavirus-covid-19-infection (Accessed 7 September 2020)

Stay at home: guidance for households with possible or confirmed coronavirus (COVID-19) infection, GOV.UK – Public Health England. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-stay-at-home-guidance/stay-at-home-guidance-for-households-with-possible-coronavirus-covid-19-infection [1]

[4] Statistics yearbook 2019, StepChange. Available at: https://www.stepchange.org/policy-and-research/2019-personal-debt-statistics.aspx

[5] Individual Insolvency Statistics, Q4 October to December 2019, GOV.UK – The Insolvency Service, Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/861179/Commentary_-_Individual_Insolvency_Statistics_Q4_2019.pdf

[6] End of Year Stats: 2019/20, The Trussell Trust. Available at: https://www.trusselltrust.org/news-and-blog/latest-stats/end-year-stats

[7] UK food banks report busiest month ever, as coalition urgently calls for funding to get money into people’s pockets quickly during pandemic, The Trussell Trust. 3 June 2020. Available at: https://www.trusselltrust.org/2020/06/03/food-banks-busiest-month/

[8] Debt advice during coronavirus: July 2020, StepChange. Available at: https://www.stepchange.org/Portals/0/assets/pdf/stepchange-covid19-data-report-july-2020.pdf

[9] Coronavirus: Bailiffs return but are told not to shout, BBC. 24 August 2020. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-53887877

[10] Coronavirus: Eviction ban to be extended by four weeks, BBC. 21 August 2020. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-53851945

[11] Many face financial double whammy at end of October, Standard Life Foundation. 2 September 2020. Available at: https://www.standardlifefoundation.org.uk/news/latest-news/articles/eme…

[12] Excess debts: who has fallen behind on their household bills due to coronavirus?, Citizens Advice. 21 August 2020. Available at:

[13] Monetary Policy Report: August 2020, The Bank of England. Available at: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/monetary-policy-repor…

[14] Who wins and who pays? Rentier power and the Covid crisis, IPPR. 13 May 2020. Available at: https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/who-wins-and-who-pays

[15] Monetary Policy Report: August 2020, The Bank of England. Available at: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/monetary-policy-repor…

[16] Who wins and who pays? Rentier power and the Covid crisis, IPPR. 13 May 2020. Available at: https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/who-wins-and-who-pays

[17] Council tax debt collection isn’t efficient or effective, Citizens Advice. 2 December 2019. Available at:

[18] Collection rates and receipts of council tax and non-domestic rates in England 2019-20 (updated), GOV.UK – Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo…

[19] A new jobs protection and upskilling plan, TUC. 4 September 2020. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/new-jobs-protection-an…

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox