Work intensification

The TUC is the voice of Britain at work. We represent more than 5.5 million working people in 48 unions across the economy. We campaign for more and better jobs and a better working life for everyone, and we support trade unions to grow and thrive.

This report is a compilation of trade union case studies showing how ‘work intensification’ is a growing problem, across a number of sectors and occupations, with negative consequences for working people. The case studies give a real life perspective of how work intensification is affecting working people. They show how unions are negotiating with employers to come up with solutions to tackle work intensification.

What is work intensification?

Work intensification has been defined 1 as “the rate of physical and/or mental input to work tasks performed during the working day”. Work intensity comprises several elements, including the rate of task performance; the intensity of those tasks in terms of physical, cognitive, and emotional demands; the extent to which they are performed simultaneously or in sequence, continuously, or with interruptions; and the gaps between tasks. This report looks at the impact of workers having to pack more work into working hours and work spilling over into their private lives.

Is work intensifying?

Work is intensifying.

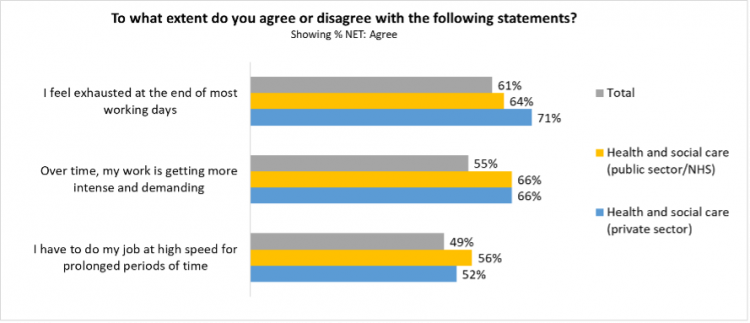

TUC polling 2 shows that a majority of workers (55 per cent) feel that work is getting more intense over time. Three out of five (61 per cent) workers polled felt exhausted at the end of each day.

Why is work intensification a problem?

High and rising work intensity matters because of its detrimental impact on health, safety and well-being.

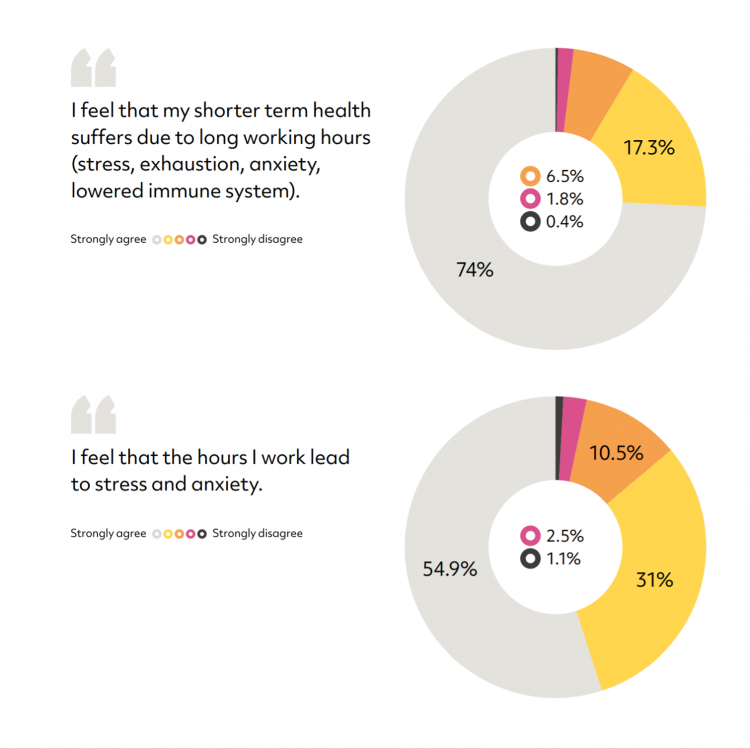

A range of health effects are associated with intensive working practises, with long hours known to be a major cause of fatigue.

When workers are tired, or under excessive pressure, they are also more likely to suffer injury, or be involved in an accident. Fatigue results in slower reactions, reduced ability to process information, memory lapses, absent-mindedness, decreased awareness, lack of attention, underestimation of risk, reduced coordination etc.

Fatigue is said to cost the UK £115 - £240 million per year in terms of work accidents alone.3

Long term-ill health conditions caused by overwork include hypertension and cardiovascular disease, digestive problems, and long-term effects on the immune system, increasing risk of autoimmune disease diagnoses. It can even result in death: one study found that in 2016, 745,000 people worldwide died as a result of working long hours alone.4

How do people experience work intensification?

This report includes case studies, provided by several unions, across a range of sectors and occupations, showing how work intensification is affecting working people.

The examples show how and why working people think that work is intensifying. They highlight the impact that work intensification has on their health and well-being, the services they deliver and on their relationships with families and friends.

The case studies show many factors can cause work intensification. For example, the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) highlights that staff shortages can lead to midwives working consecutive shifts. And the education union NASUWT shows how excessive scrutiny and oversight in the workplace can lead to work intensification because of the emotional demands placed on teachers.

Our report shows the ways unions are tackling this problem through collective bargaining strategies to tackle work intensification.

We also set out an action plan for government to safeguard workers against the effects of work intensification and stop the escalating recruitment and retention crisis in public services.

- 1 Green, F. (2001). “It’s been a hard day’s night: The concentration and intensification of work in late twentieth-century Britain”. British Journal of Industrial Relations 39(1): 53–80.

- 2 Nationally representative polling conducted by Thinks Insight & Strategy for TUC. 2,198 workers in England and Wales in August 2022.

- 3 Human factors: Fatigue, Health and Safety Executive Website

- 4 17 May 2021). “Long working hours increasing deaths from heart disease and stroke: WHO, ILO”. World Health Organization

Work intensity, or work effort, is a measure of the physical or mental input an individual puts into their work.5

Work intensity comprises several elements, including the rate of task performance; the intensity of those tasks in terms of physical, cognitive, and emotional demands; the extent to which they are performed simultaneously or in sequence, continuously, or with interruptions; and the gaps between tasks.” 6

High work intensity is associated with high workload, working to tight deadlines and working at speed.7

Work intensification doesn’t just take place during contractual hours. It can also spill over into workers’ private lives.

The Eurofound 6th European Working Conditions Survey 8 identified 13 factors that could contribute towards work intensification:

Number of tasks and the speed at which it can be accomplished

- Working at very high speed (three-quarters of the time or more)

- Working to tight deadlines (three-quarters of the time or more)

- Enough time to get the job done (never or rarely)

- Frequent disruptive interruptions

Pace determinants and interdependency

- Interdependency: three or more pace determinants

- Work pace dependent on:

- the work done by colleagues

- direct demands from people such as customers, passengers, pupils, patients, etc.

- numerical production targets or performance targets

- automatic speed of a machine or movement of a product

- the direct control of your boss

- Emotional demands

- Hiding your feelings at work (most of the time or always)

- Handling angry clients, customers, patients, pupils, etc. (three-quarters of the time or more)

- Being in situations that are emotionally disturbing (a quarter of the time or more)

This useful list shows that a wide range of factors can cause work intensification.

Our case studies show that other factors such as excessive employer oversight and lack of peer support can also lead to people feeling that work is becoming more intense. The NASUWT case study below looks at this further.

NASUWT reports that work intensification is a key concern for teachers, alongside declining real terms pay and a lack of support in managing poor pupil behaviour. Independent research also demonstrates that work intensification is a primary issue of concern for teachers. Work intensification has a detrimental impact on teachers’ well-being, with this being one of the key drivers for teachers leaving the profession.

Increasing workloads

The UK Office of Manpower Economics (OME), an independent organisation that provides impartial secretariat support to the independent Pay Review Bodies, carried out research to measure the impact of pay, rewards and other employment characteristics on the retention of teachers. At the core of the study was a quantitative survey conducted with teachers in England. The research followed a House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts (2018) report that stated that the number of secondary school teachers has been falling since 2010 and the number of teachers leaving for reasons other than retirement has been increasing since 2012. Coupled with the fact that the number of pupils is increasing, and is expected to keep increasing in the future, this has placed increased pressure on the supply of teachers (House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, 2018).

The key findings showed that:

- workloads are significantly increasing for teachers and that this is having a serious impact on teacher retention

- pay and rewards are important retention factors, but they are not the only factors that shape teachers’ retention choices

- workplace characteristics (workload, school culture and teaching environment) are highly valued by teachers. Teachers would be willing to trade-off higher pay/rewards to work in supportive environments with fewer challenges from pupil behaviour

- Respondents reported heavy workload. Nearly half of the sample stated they work 21 per cent to 50 per cent more than their contract hours and almost a third report working 51 per cent to 100 per cent more.

This finding is in line with previous evidence 9 , for instance by the Department for Education, that the workload associated with teaching is the biggest cause of retention issues.

Work intensification

NASUWT is keen to flag up the distinction between work intensification and increasing workloads.

Whilst there is undoubtedly an overlap, with increasing workloads contributing towards work intensification, teachers’ work has intensified in other ways which has led to negative impacts on their health and wellbeing. Teachers are under increasing levels of scrutiny and this new work dynamic leads to teachers working in a more intense environment.

NASUWT reports that teachers have lost a large degree of autonomy and professional agency. They are now subjected to a level of scrutiny and oversight that is debilitating. Examples include:

- Excessive lesson observation, with teachers increasingly find their lessons observed. These are viewed as management checks on teacher performance and create a stressful environment for teachers to work in. Conducted appropriately, lesson observations have always had an important role to play in supporting professional classroom practice. However, they have increasingly been used solely to monitor and scrutinise the compliance of teachers with the expectations of employers. While lesson observations can provide information to support fair performance management processes, there is a need for practice to place much greater emphasis on their role in supporting professional development.

- ‘Book looks’ – employers pick out a sample of pupils’ exercise books and use these to make an assessment about the quality of the teacher’s work.

- Planning of lessons are subject to checks from independent/internal auditors.

- Pupil attainment figures are used to assess a teacher’s performance.

In 2006, the Government and trade unions through the former Workforce Agreement Monitoring Group (WAMG) agreed a more proportionate and development-focused approach to performance management. This approach, underpinned by regulations, ensured that the use of lesson observations and other such evidence was proportionate to need and was used as a means of informing professional reflection on professional practice. Critically, it involved teachers and leaders as active partners in their performance management and allowed them to identify their professional development needs and ensure that they were given support in working towards their career progression aspirations.

In 2012, the former Coalition Government removed most of the underpinnings of this supportive and developmental system. Instead, it encouraged an approach which shifted

the focus of performance management towards one focused narrowly on punitive scrutiny of teachers' and leaders' work. Instead of fostering professional dialogue about performance, it rendered formal appraisal in too many cases into an exercise in which teachers and leaders were required to provide evidence annually of their competence against crude checklists of performance. The hard links established between successful completion of this progress and access to pay progression served only to undermine further the positive potential of performance management to assist teachers and leaders in developing their skills, enhancing their practice, and advancing their careers.

A combination of these monitoring measures creates a stressful environment for teachers to work in.

Lack of peer support has contributed to work intensity

Teaching has become more isolated. Teachers used to be able to access peer support in communal areas such as staff rooms, to discuss work issues, de-stress and seek support from colleagues. Time constraints and lack of physical space to meet up has removed this vital support for teachers.

NASUWT raise an interesting point that the architecture of new schools often does not include space for a staff room. These are vital spaces where teachers can gather and de-stress, tackling the effects of work intensification.

There is OECD evidence that demonstrates the importance of collaboration and having an environment that fosters collegiality. The Teaching and Learning International Survey from 2018 10 says that “teachers who report engaging in professional collaboration with their peers on a regular basis also tend to report higher levels of self-efficacy (in all countries with available data), as well as higher levels of job satisfaction”.

Impact on teachers

The impact of work intensification and increasing workload on the teaching profession has been profound. The extent of these workload pressures is confirmed in the results of the most recent OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS). 11 The survey found that teachers’ average working time remains at unsustainable levels. Primary teachers' average working hours were reported at 52.1 hours per week, with over a quarter of full-time secondary teachers subject to a working week of 60 hours or more. Recent DfE research 12 emphasises the importance of excessive workload as a factor in teachers' decisions to exit teaching.

In the NASUWT’s annual survey of the state of the teacher and school leader workforce, The Big Question, many of the impacts of the decline in the quality of work were set out in stark terms. The survey showed that:

- only 14 per cent of respondents said they would recommend teaching as a career

- 73 per cent have seriously considered leaving their current job and 66 per cent have considered leaving the teaching profession altogether because of the unremitting pressures they are facing

- 86 per cent agreed that they work too hard for too little reward

- 63 per cent stated that they feel constantly evaluated and judged

- 57 per cent agreed that they are held responsible for problems over which they have no control

- only 28 per cent think that their professional judgement is respected in their school

- 82 per cent have experienced more workplace stress while 81 per cent believe that the job has adversely affected their mental health

- 83 per cent of teachers and leaders have experienced anxiety and 79 per cent said they lost sleep and

- 52 per cent reported adverse mental health outcomes were the result of workload.

The role of OFSTED in tackling work intensification

In 2019 OFSTED launched an inspection framework that would pick up issues of workloads and well being. Because of the pandemic the new framework was not embedded into the system until September 2021.

OFSTED has identified 13 through its regular inspections, that workload and the impact on teacher is wellbeing is a serious problem. It has also identified that this is affecting the educational attainment of pupils.

NASUWT welcomed the framework but would like to see OFSTED doing more to ensure the validity and reliability of assessment around work intensification. NASUWT has disputed some of the findings.

NASUWT interventions

The NASUWT remains deeply concerned by the Government's failure to take sufficient action to address the causes and consequences of excessive workload. Nevertheless, it has been possible to make progress in some areas. For example, following representations made by trade unions, the Department for Education established the Teacher Workforce Advisory Group.

These groups, which drew together representatives from trade unions alongside educational specialists and practitioners, sought to identify and address practices in three of the principal drives of excessive and unnecessary teacher and leader workload: marking, lesson planning and the use of pupil performance data in assessment.

The outcomes of these reports, published in 2016, set out helpful guides to practice in these critical contributors to workload burdens. Copies of these reports can be accessed in the Reports from independent groups, a section of the Reducing school workload government webpage. 14 Their outcomes were endorsed by the DfE, Ofsted and the main teacher and leader unions. They were launched by the former Secretary of State for Education, Nicky Morgan, at the NASUWT's 2016 Annual Conference.

Where the recommendations set out in the reports have been adopted, they have assisted in addressing workload caused by poor approaches to marking, planning and assessment. However, the Government has failed to take more effective action to ensure their wider use. As a result, their impact on work intensification and excessive and unnecessary workload will remain marginal until this action is taken.- 5 Hunt, T. and Piackard H. (27 April 2022). “Harder, better, faster, stronger? Work intensity and ‘good work’ in the United Kingdom”, Industrial Relations Journal, volume 3, issue 53, pp. 189-206

- 6 Ibid. 1

- 7 Ibid. 5

- 8 Parent-Thirion, A; Biletta, I; Cabrita, J; Vargas Llave, O; Vermeylen, G; Wilczyńska, A; Wilkens, M. (17 November 2016). “Sixth European Working Conditions Survey – Overview report”. Eurofound.

- 9 March 2018). “Factors affecting teacher retention: qualitative investigation”. CooperGibson Research, Department for Education.

- 10 2020). “A Teachers' Guide to TALIS 2018: Volume II”. OECD.

- 11 Jerrim, J; Sims, S. (June 2019). “The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 Research report”. UCL, Institute of Education.

- 12 September 2017). “Analysis of school and teacher level factors relating to teacher supply". Department for Education.

- 13 22 July 2019). “Summary and recommendations: teacher well-being research report”. OFSTED.

- 14 15 June 2023). “Reducing school workload”. Government website.

There is lots of evidence to show that work is intensifying.

TUC polling

Polling 15 commissioned by the TUC revealed that:

- 61 per cent of workers feel exhausted at the end of most working days.

- 55 per cent of workers feel that work is getting more intense and demanding, over time.

We also asked workers what work-related actions they are doing more of, outside of contractual hours, compared to 12 months ago. The findings showed that:

- 36 per cent of workers are spending more time outside of contracted hours reading, sending and answering emails.

- 32 per cent of workers are spending more time outside of contracted hours, doing core work activities.

This increase in work-related actions outside of contractual hours is indicative of work intensification. High workloads which are not achievable during contractual hours, spill over into workers’ private lives, meaning they are undertaking work in the evenings, whilst at home.

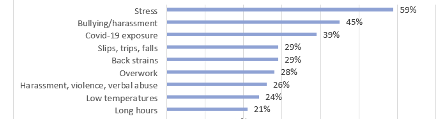

In addition, union health and safety representatives told us that factors relating to work intensification are some of the most common workplace hazards they encounter 16 :

- 59 per cent identified stress as one of the most common hazards.

- 45 per cents said bullying and harassment by management and colleagues was a common concern in their workplace.

- 28 per cent said overwork specifically was a safety concern widespread among their members.

Recent academic research

A number of research reports, published over the last couple of years, confirm that work is intensifying. These are discussed below.

Working still harder

The Skills and Employment Survey (SES) is a consistent series of nationally representative sample surveys of employed individuals in Britain, conducted at five- or six-year intervals. The surveys ask workers about their perceptions of work intensification. Respondents are asked how much they agree or disagree with the statement, “My job requires that I work very hard”. The survey also asks respondents to rate on a scale “How often does your work involve working at very high speed” and “How often does your work involve working to tight deadlines”.

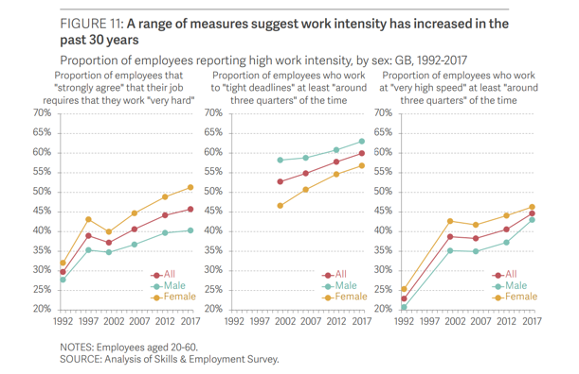

Analysis of this large dataset 17 confirms earlier studies that had reported a rapid intensification of work in Britain in the first part of the 1990s followed by a plateau of flat or declining work intensity in the latter part of that decade. The story from 2001 on is one of renewed work intensification. Between 2001 and 2006, two out of the three indicators of work intensification (mentioned above) rose, as did the overall index; from 2006 until 2017 all three indicators and the overall index increased.

Most notably, the proportion of workers in jobs where it was required to work at ‘very high speed’ for most or all of the time rose by 4 percentage points to 31 percent in 2017.18

Work experiences: Changes in the subjective experience of work

Resolution Foundation analysis 19 shows how the pace of work has increased in Great Britain since the early 1990s across several different metrics.

The graph below shows the share of employees who “strongly agree” that their job requires that they work “very hard” has increased from 30 per cent in 1992 to 46 per cent in 2017. The share of employees who work to “tight deadlines” for at least “around three quarters” of the time has increased from 53 per cent to 60 per cent. The share of employees who report they work at “very high speed” for at least “around three quarters” of the time has almost doubled from 23 per cent to 45 per cent.

The share of employees who report that their work is “always” or “often” stressful has risen from 30 per cent in 1989 to 38 per cent in 2015. Strikingly, the proportion of those who report they are often stressed in skilled manual roles (such as driving or care work) has doubled over the same 26-year period, from 18 per cent to 41 per cent.

These findings demonstrate significant increases in work intensity particularly those working at very high speed and those that strongly agree that their job requires them to work ‘very hard'.

- 15 Nationally representative polling conducted by Thinks Insight & Strategy for TUC. 2,198 workers in England and Wales in August 2022.

- 16 Health and Safety Reps Survey 2023, Trades Union Congress.

- 17 Green, F; Felstead, A; Gallie, D; Henseke, G. (March 2022). “Working Still Harder”. ILR Review, Volume 75, Issue 2

- 18 Green, F; Felstead, A; Gallie, D; Henseke, G. “Work Intensity in Britain: First Findings from the Skills and Employment Survey 2017”.

- 19 Shah, K; Tomlinson, D. (September 2021). “Work experiences: Changes in the subjective experience of work”. The Resolution Foundation.

The Resolution Foundation reports that “the changing composition of the workforce (both in terms of personal characteristics and the occupations and industries in which people work) explains only a small part of these trends, suggesting that something fundamental has changed in the nature of work over the last 30 years.”

Covid-19 and Working from Home Survey

The Covid-19 pandemic and large-scale shift to working from home for some groups of workers also led to work intensifying in some roles. The shift to home working has, in many cases, blurred the boundaries between work and home for many people. This has led to work-related activities seeping into vital rest time, impacting both workers and their families.

A report drawing on the findings from a Covid-19 and Working from Home Survey 20 highlighted that:

“Large numbers experienced increases in volumes of work (32 per cent), intensity of work (38 per cent), pace of work (32 per cent), pressure of work (32 per cent). Variety of work is less than in the office, but skill and personal control over work were greater when WFH. 39 per cent report that managers contact workers for progress reports at least once a day. 45 per cent report that automated systems monitor work activity and 38 per cent that they monitor work rate. 29 per cent reported working extra time in order to complete tasks that could not be completed during their scheduled working time.”

A sizeable minority (29.1 per cent) of survey respondents said they are now expected to work extra time if tasks are not completed in allotted time, a finding that is consistent with the reported increases in the volume and pressure of work.

The study was initiated by authors and the STUC and supported by several trade unions (CWU, Unite the Union, TSSA, Unison, Accord, PCS) and campaign group Hazards.

Concerns about working from home leading to work intensification further strengthens the case for working from home policies to be negotiated with trade unions to ensure safeguards are included. Unions negotiate flexible working policies that ensure that workers, whose roles can be done at home, get the added flexibility and benefits that working from home can bring. Unions will also negotiate safeguards in policies to ensure that working from home doesn’t infringe basic rights such as a right to family life, right to privacy and entitlements to adequate rest breaks.

International comparisons

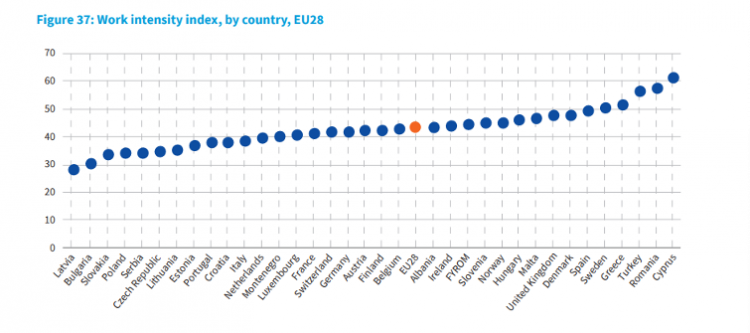

Analysis of work intensity indicators in the European Working Conditions Survey 2015 and the European Social Survey 2010 showed that the United Kingdom ranked highest among the EU28 for the percentage of workers reporting that they work to tight deadlines, second for working very hard and average for working at high speed. 21

How do we compare to our European counterparts?

Certain groups of workers are experiencing work intensification more than others.

TUC polling and research carried out by the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute and Newcastle University Business School 22 , both show that women are more likely to work with high work intensity than men.

Our polling shows that women are more likely to say they feel exhausted at the end of most working days (67% to 56%) and that work is getting more intense (58% to 53%).

Women are overrepresented in sectors such as education and health and social care. In 2021/22, 75.5% of schoolteachers were women. 23 In the health care workforce almost 80 per cent of non-medical health service staff are women compared to 46 per cent of the wider workforce. 24

These are sectors where staff shortages and other factors, such as excessive scrutiny and long working hours, have led to increased work intensification.

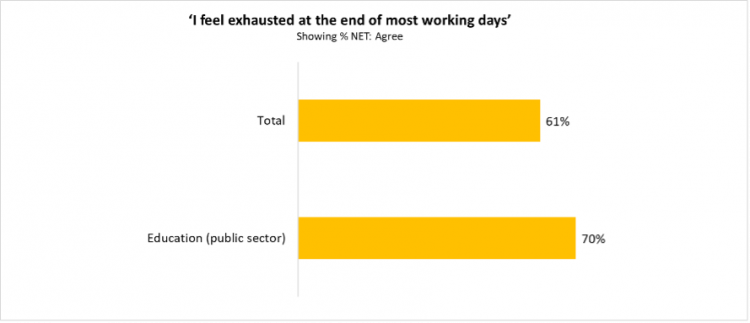

TUC polling reveals that people working in healthcare and education are particularly likely to feel the exhaustive effects of work intensification.

Those working in education are more likely to agree that they’re exhausted at the end of most working days.

We need legislative measures to stimulate collective bargaining and make it easier for unions to speak with and represent workers. This includes broadening the scope of collective bargaining rights to include work organisation, including the introduction of new technologies, and the nature and level of staffing. Collective bargaining is the key safeguard to ensure that women do not bear the brunt of work intensification.

There are many factors that have contributed to work intensifying.

Decline in collective bargaining

When workers come together to negotiate with their employer, this is known as collective bargaining. Collective bargaining can cover issues like work organisation as well as pay and other key terms and conditions. Work organisation refers to how work is planned, organised and managed within companies and to choices on a range of aspects such as work processes, job design, responsibilities, task allocation, work scheduling, work pace, rules and procedures, and decision-making processes.25 Unions can negotiate the key components of a job to prevent work intensification.

However, industrial changes have combined with anti-union legislation to make it much harder for people to come together in trade unions to speak up together at work. Union coverage in the UK has declined significantly from its peak 40 years ago. In 1979 union density was 54 per cent and collective bargaining coverage was over 70 per cent; in 2022, they were 22.3 per cent and 26.6 percent respectively, with just 13.1 per cent of the private sector protected by a collective agreement.26 Over this period the scope of the bargaining agenda has narrowed significantly - by 2011 pay was the only issue still covered in a majority of collective agreements.27

Because of this, there is less union negotiation around work organisation, resulting in work intensification.

Changes to industrial organisation and management practices over the last few decades

The authors of Working Still Harder28 suggest that ‘outsourcing, subcontracting, joint ventures, and long-term contractual arrangements across value chains—and in the parallel spread of new management practices with associated reorganization of work’ could also be a cause of work intensification.

This is also confirmed in a report on outsourcing, “Outsourcing the cuts: pay and employment effects of contracting out, that was commissioned by UNISON.

This report found that the intense pressure to meet key performance indicators and targets increases work intensity for staff while decreasing the level of autonomy and control they have over their work. A paper from ACAS cites a number of studies suggesting that one result of outsourcing has been the “increased propensity to manage workers by results” and the way in which this is done can lead to lower levels of job satisfaction, higher stress and higher turnover. In turn this can be compounded by the lack of employee influence over “the pace of work and the targets to be met”, which is ultimately determined by the contracting authority, not the worker’s direct employer. While working to demanding performance objectives has become a common feature across the private sector since the 1980s and more recently across the public sector, some studies show that this is particularly intense on outsourced contracts.

Working Still Harder also points out that work intensification may be a consequence of the closer control and discipline afforded by modern forms of management, including:

- Just In Time (JIT) and Total Quality Management (TQM) practices that originated in Japan

- lean production systems

- high-performance work practices including teamwork

- and management through target-setting. Target-setting is assumed to be a key part of efficient management.

Meeting customer expectations

Industrial and cultural change have meant that customers expect prompt delivery of goods and services. The emergence of the gig economy and technological changes have facilitated this. But increased customer expectations have contributed towards work intensification. This is confirmed in the recent Resolution Foundation report, which states “it is ‘clients or customers’, though, that have become the most-cited determinant of how hard people work, with 59 per cent of employees reporting that they mattered in 2017, up from 37 per cent in 1986.”

Staff shortages, redundancies, reduced workforces

Unions have reported 29 that staff shortages caused by a lack of public sector funding and redundancies has led to work intensification, with workers who remain in the organisation picking up the work that still needs to be done.

Austerity policies throughout the last decade have meant many job losses and organisational change in the public sector.30 Professor Les Worral points out that since the 2010 election, the public sector has been the focus of a sustained ideological attack with the sector being subjected to waves of destabilising change: over 631,000 public sector jobs have disappeared at a time when the demands on the sector have clearly increased. There is clear evidence that cost-reduction driven organisational change had led to considerable work intensification and extensification in the public sector. Public sector managers reported that the pace of work, the volume of work and the pressure put upon them to work longer hours to cope with more burdensome volumes of work had all increased. The effect of redundancy and delayering had been to increase role overload in the public sector. Significant proportions of public sector managers reported that working long hours was having a very negative effect on their health, their wellbeing and on their non-working lives.

The case study from the RCM below clearly shows the impact of staff shortages on work intensification.

RCM work intensification case study

NHS employees in England are invited to participate in the annual NHS staff survey. 2022 saw a response rate of 46 per cent, with 636,34831 staff responding.

This revealed that the levels of work intensification for midwives have become intolerable.

Only 7.4%32 per cent of midwives said they had enough staff to provide a safe service. 58.3% per cent of staff are exhausted and regularly feel burnt out because of their workload. 62.8% 33 per cent of midwife respondents said they have felt unwell due to work-related stress.

This is an unsustainable situation impacting upon an already depleted workforce. RCM reports that England has seen midwife numbers plummet by around 600 34 over the past year 2021/2022 on top of an existing and longstanding shortage of over 2000 midwives. RCM analysis of new figures from NHS Digital show that this drop has affected every English region.

One example of significant change, that has lead to work intensification, is the role of midwives in providing neo natal transitional care. On the post-natal wards care of the newborn, who may require intra venous drug therapies and constant observation is performed by midwives, increasing their workload. A 28 bed post-natal ward with 28 cots has a bed occupancy of 56 but invariably staffing levels do not reflect this. Midwife shortages are a significant driver of work intensification. In many units safe levels of staffing are not being met. This leaves those on duty dealing with the workload of many.

Community midwives traditionally provide a 24 hour on-call service but for a number of years have been called into the acute hospital settings at night to make up staff numbers. This impacts upon community staffing levels the following day when the midwives try to catch up on sleep, often needing to work part of the following day to cover clinics – this is unsustainable and affecting health and wellbeing of midwives and support workers. More recently hospital midwives who have not traditionally worked on-call have also been expected to work on-call on non-working days to cover shortages on labour ward, this impacts further on workloads and the health and safety of staff.

The RCM is tackling work intensification by engaging and negotiating with employers to bring in different shift patterns which would help meet staff shortages, help midwives with their work/life balance and alleviate work intensification issues. For example, twilight shifts when midwives would work between 8pm-12am instead of longer shifts.

The RCM has refreshed its 2016 campaign ‘Caring for You’ – which challenges employers to tackle the drivers of work intensification and ensure that they are complying with statutory health and safety requirements.

The RCM has rewritten their Caring for You Charter with 6 key principles:

Culture - Promote a positive, inclusive culture where staff feel valued, respected and invested in, and ensure a safe and effective learning environment for students.

Action - To work in partnership with RCM branch and workforce business partners, to implement bespoke action plans based on local issues, identified by the maternity team.

Responsibility - Implement robust health and safety strategies to prevent damage to staff wellbeing, ensuring zero tolerance of violence and/or aggression. As an employer we are committed to providing a safe and healthy working environment.

Inclusive - Implement actions to address inequality in the workplace, ensure inclusivity and protect staff from bullying, incivility, plus all negative and undermining behaviours.

Nurture - Ensure a positive experience for all new starters, newly qualified and returners to the service. Promote attractive and innovative shift patterns which will be easily accessible to Midwives and MSW’s.

Good to Great - Work in partnership to monitor and evaluate progress in relation to our action plans and the experience of all midwives, MSWs and students, improving and adjusting accordingly.

The employers are asked to sign the charter and commit to negotiations via a working group, which is setup by the Trust and the RCM Branch. They look at each of the six principles over a period of 12 months and agree a plan on how they can improve their services in line with these principles. The group will review employer evidence; what changes are required and how they are established ongoing evaluation working with the Trust values and visions.

Once established and sustained the employer receives the RCM Caring for You award.

Inadequate enforcement of Working Time Regulations

Existing legal requirements under the Working Time Regulations contain important rights for workers which could help safeguard against work intensification and the consequential health and safety risks.

Workers have important rights relating to:

- maximum weekly working time

- night work limits

- health assessments for night work

- time off between shifts

- rest break entitlements

- paid annual leave entitlements.

These vital rights create space for workers to have time away from the workplace. It gives workers time away from the wide range of factors that cause work intensification, such as working at speed, working without proper rest breaks, and having work pace determined by someone else.

Enforcement of these rights is ineffective. This means one of the key tools to tackle work intensification is being lost. The Health and Safety Executive is responsible for enforcement of the maximum weekly working time limits, night work limits and health assessments for night work. However, its annual report, 35 which contains details of their enforcement activity, makes no mention of any enforcement activity in this area. Data on the HSE website 36 also suggest that there have been no convictions in relation to breaches of the Working Time Regulations in the last 10 years. In the last year there has been just one enforcement notice relating to Working Time Regulations. What’s more, the HSE is becoming more and more limited in its capacity due to shrinking resourcing, with its budget cut by almost a half: funding for 2021-22 was 43 per cent down on 2009-10 in real terms. 37

Anxiety about changes to pay and working hours

Research by Tom Hunt and Harry Pickard 38 shows that individuals who are anxious about future changes at work that may reduce their pay and those who are anxious about unexpected changes to their hours of work are more likely to work intensely.

The research shows that if an individual believes they might lose their job in the next year this has zero effect upon an individual's degree of work intensity.

This suggests that individuals may work more intensely as a result of uncertainty about potential changes to specific features of their job (in this instance, pay and working hours), rather than being motivated to work with high intensity because they fear losing their job.

The research also considers the role of personal motivation in determining work intensity by looking at how much influence an individual personally has on how hard they work. The results show those workers who report that they can influence how hard they work to ‘a great deal’ or ‘a fair amount’ do not have a higher degree of work intensity. This further supports the notion that the factors driving work intensity are related to unease about pay and hours, not personal (intrinsic) motivations.

This research is significant as it indicates that workers in precarious employment, who face great uncertainty over income and working hours, are likely to feel more pressure to work intensely.

Use of technology is a key driver of work intensification

TUC polling shows that one third of workers say they have been impacted by the introduction of new technology into their workplace, within the last 12 months.

New technologies can bring significant benefits for both the employer and worker. But the introduction of new technologies need to be managed effectively, and in consultation with the workforce, to ensure that productivity gains deliver improved working conditions and not work intensification.

58 per cent of the workers that the TUC polled say that the new technologies have led them to doing more work in the same amount of time. This is concerning as unions are reporting that technologies are being introduced without the necessary safeguards that would prevent work intensification and the detrimental impact on workers’ health and safety and wellbeing.

New technologies can contribute to work intensification in different ways.

Firstly, computer usage and software that enables workers to utilise efficiency tools such as calendars, emails, task lists etc. – all contribute to making people do more work often without sufficient rest breaks. Research 39 carried out by Francis Green, Alan Felstead, Duncan Gallie and Golo Henseke draws the link between jobs where computer use is essential and high work intensity. They state: “Because of previous evidence about the link between technology and work intensity, we divided the sample into jobs for which the use of a computer was essential (labelled High Computing), and all other jobs (Low Computing). For two out of our three measures of required work effort, High Computing jobs required substantially higher work intensity.”

Secondly, new technologies, workforce data and algorithmic management are driving work intensification by making people work longer and harder.

Our report, ‘Technology managing people: The worker experience’ 40 looks at this in much more depth. But below we pick out some of the key technological drivers of work intensification.

- Digital technologies intensify human activity at work, by increasing the number of tasks completed by people. A BFAWU rep highlighted that “technology is aiding employers with setting targets, like pick rates for example”. Algorithmically set productivity targets can be unrealistic and unsustainable – forcing people to work at high speed. Algorithmic management can also force workers to work faster through constant monitoring, including monitoring the actions they perform and their productivity.

- Worker ratings, often determined by an algorithm, will place immense pressure on workers. Customers are asked to provide ratings on a worker’s performance. This data is then used to create worker ratings which in turn could determine the pay rates and working hours of workers. Because of this, workers are incentivised to work harder and longer to maintain their worker ratings and secure future employment.

- Workplace technologies facilitate constant real-time evaluation of performance. Sarah O’Connor in the Financial Times 41 highlighted that handheld satnav computers are used to give warehouse staff directions on where to walk next and what to pick up when they get there and also to measure a worker’s productivity, the data then being fed back to the employer.

- Workplace monitoring and surveillance can also lead to work intensification as workers fear being sanctioned for spending time away from work. For example, with the increase in working from home, more employers are using software to monitor workers’ whereabouts.42 Some monitoring programs record keystrokes or track computer activity by taking periodic screenshots. Other software records calls or meetings, even accessing employees’ webcams. Some programmes even enable full remote access to workers’ systems.

- Automated decision-making systems can take over the control of work (e.g. content, pace, schedule) through, for example, worker direction, and little will be left to be decided by the worker. Loss of autonomy and job control – as we can see from the NASUWT case study below – can be a key driver of work intensification.

- Portable digital devices are leading to a blurring of work/home boundaries. As we flagged above, our recent polling found that 36 per cent of workers are spending more time outside of contracted hours reading, sending, and answering emails. This leads to working time encroaching on a person’s right to private and family life. The extension of the workday into people’s private lives is an indication that work is intensifying.

A case study from campaign group Connected by Data 43 demonstrates how technology can drive work intensification.

Amazon’s technologically intensive business practices have coined the term the ‘Amazonian Era’.

In the context of the first industrial dispute involving the company in the UK, warehouse worker Garfield Hylton talks about how the company’s use of algorithmic management affects his health and wellbeing.

Garfield Hylton, 59, is a Universal Receiver for Amazon. He has worked at the fulfilment centre in Coventry for almost 5 years.

Amazon gathers data from handheld scanners, which are used to scan an item every time it moves in the logistical process. As well as tracking the items, the data is used for performance management. It collects data to assess against a target ‘rate’ of scans, and to monitor how much workers are considered to be Time Off Task (TOT).

“When we execute an action, it registers as being completed, but if our performance slumps in idle time or Time Off Task the management will ask us why that’s happened,” Garfield says.

However, he adds, “TOT often happens due to system error. The problems normally are things that don't scan, there isn't any work at your station, or you have issues with your station. The system doesn't always recognise this context. I have learnt to keep an extensive log of where I go and what I do in case I get asked why I’ve had a spike.”

As there is no appreciation of context by the software, the lack of discretion can lead to punitive and inappropriate outcomes. The algorithm does not factor in for differences such as illnesses, abilities, personal circumstances or age.

Even small periods of TOT can damage a worker’s performance rate. Garfield, who has diabetes, says that even getting to a toilet in the giant warehouse can cause a spike in your TOT.

“If you have an idle time of an hour because you go to the loo three times in a 10 hour shift for a bodily function you’ll be called in for a conversation about why you’ve had that many spikes.

Ultimately we get on with it but it’s stressful having to constantly prove that you’re not making errors. You shouldn’t have to do that at work.”

Though workers are assessed against a target, they are not told what that target is. The opaque target drives workers to compete with each other to ensure their performance rate is in the top 95 per cent. Every day, workers who are in the bottom 5 per cent must meet with management. If a worker is subject to five meetings, they can be dismissed.

“Your performance is assessed throughout your entire shift, managers are constantly scanning your rate throughout the day,” Garfield says, adding that “it’s really about greed, they’re constantly cracking the whip. New workers have a speed mindset because they’re told that they will be considered for a permanent contract if they work the fastest rate, so they’re being made to work their socks off.”

Appearing at the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Select Committee in November 2022, Brian Palmer, Amazon’s EU Head of Public Policy maintained that data gathering is “not primarily or even secondarily to identify underperformers” for disciplinary or performance management purposes, and was focused on worker safety and logistical accuracy.

Following these statements, law firm Foxglove submitted a supplemental briefing to the committee in December 2022. Foxglove stated that Mr Palmer’s statements were “misleading at best – and at worst, deceptive.” Drawing on internal company documents made available via legal proceedings in the USA, Foxglove demonstrated that Amazon managers are in fact instructed to identify “top offenders”, with documents detailing the subsequent disciplinary and termination processes.

Foxglove stated that if the same or similar practise was carried out in the UK it would “likely violate UK employment law – because workers are being held to a relative standard to keep their jobs, rather than an objective and reasonable one. The practice may also raise issues under discrimination law”.

There is not yet transparency into Amazon’s policies and practises in the UK, though worker testimony and other evidence suggests a similar approach as in the USA.

Garfield talked about the effects of work intensification:

“I’m hanging in there to support my colleagues but I’m realising I’m coming to the end of my tether. I can feel my joints seizing up and I have a bad left hand from work. I’m on unpaid leave at the moment, but then you come into work where you're constantly pressurised and where management is unsupportive, it definitely knocks your resilience down a notch.”

Declining worker autonomy

Resolution Foundation research 44 highlights declining worker autonomy as another factor causing work intensification.

Its research shows that fewer employees report that their “own discretion” determines how hard they work even though the workforce has become more highly educated and more likely to work in “professional” jobs over the period. In 1992, 71 per cent of employees reported having “a great deal” of control over how hard they worked; by 2017 this share had fallen to 46 per cent.

Put simply, this suggests that work organisation, including productivity targets, pace of work and how work is done, is increasingly being decided by employers. Where individual workers and unions are not involved in discussions around work organisation it is more likely that workers will experience work intensification.

Findings from Unite the union’s large scale membership survey confirm this.

Unite survey 45 highlights unpaid overtime, work-related stress and lack of influence over the pace of work

The findings of the first Unite all members’ survey, published in December 2021, present a significant picture of members’ experiences of and attitudes to work. It was an online survey with 31,700 completed responses across all Unite sectors and regions.

The survey findings suggest that work intensification could be causing serious issues for Unite members.

Unpaid overtime

Just under a quarter (24 per cent) of respondents reported experiencing ‘unpaid overtime’ suggesting high workloads. This was particularly an issue in the Finance & Legal, Community, Youth Workers & Not for Profit, and Health sectors.

Work related stress

‘Work related mental health and stress’ was cited as the biggest concern at work by 7 per cent of respondents (although it also featured in respondents’ second and third concerns). However, when asked to identify issues they had experienced in the last 12 months, ‘work related stress’ was by far the most cited issue (by 60 per cent of respondents). It was the most cited issue experienced across all sectors, but was most acute in public services sectors such as Health (71 per cent), Community, Youth Workers & Not for Profit (71 per cent) and Education (69 per cent). This is in line with the findings of a survey of Unite Workplace Representatives published in April 2021 which found that 83 per cent of reps were dealing with an increase in members reporting mental health-related problems, a huge 18-point increase from the 65 per cent reported in 2020.

Changes to work imposed without consent

Unite members reported that changes to work imposed without consent also featured as a part of members’ work experiences. 21 per cent of respondents said that this had occurred in respect of ‘restructure and reorganisation of my job’, 15 per cent in respect of ‘changes to my contract and terms or conditions’, and 13 per cent in respect of ‘changes to my working time’. Changes to working time imposed without consent suggest that Unite members may be facing less favourable working time to pick up additional workloads.

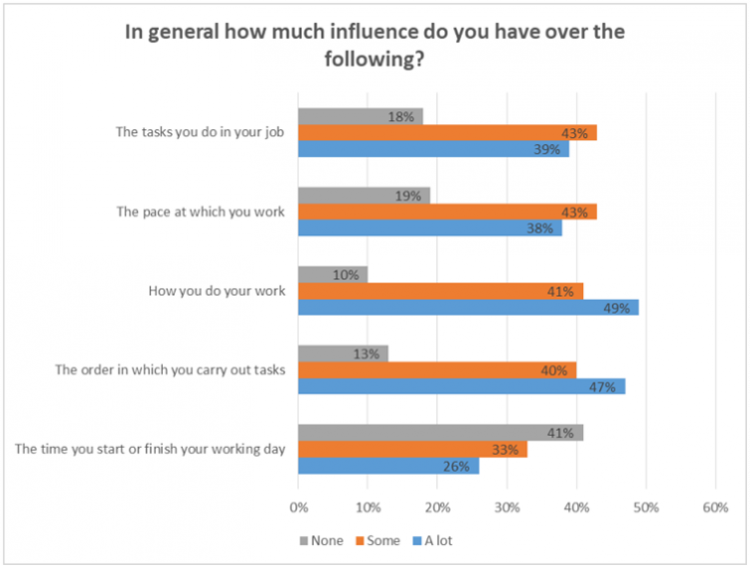

Lack of influence over elements of work

The table below, taken from the survey findings, reveals some factors which may be driving work intensification for Unite members. Only 38 per cent of Unite members felt they had a lot of say in determining the pace at which they worked, which suggests for a large number of Unite members they may be working at a pace which is too intense for them. Only 26 per cent of Unite members felt that they had a lot of say over the time they started or finished the working day. This suggests that workload issues may be determining the start/finish time for a large number of Unite members. We know that high workloads are associated with work intensification.

- 25 25 May 2023). “Work organisation”. Eurofound Website.

- 26 24 May 2023). “Trade union statistics 2022”. Department for Business and Trade.

- 27 3 September 2019). “A stronger voice for workers How collective bargaining can deliver a better deal at work”. Trades Union Congress

- 28 Ibid. 17

- 29 11 May 2020). “Many of my colleagues have been made redundant and the rest of us are expected to cover lots of their work, is there anything I can do as I feel I can’t cope?”. Prospect union website.

- 30 Worrall, L. (23 July 2013). “Austerity’s assault on the public sector has had tremendous impact on managers’ physical and psychological wellbeing”. LSE blog.

- 31 March 2023). “NHS Staff Survey 2022 National results briefing”. Survey Coordination Centre, NHS.

- 32 “NHS England survey results 2022”. Royal College of Midwives website.

- 33 National NHS Staff Survey 2022 - Detailed Spreadsheets

- 34 1 July 2022). “Drop in midwife numbers accelerates”. Royal College of Midwives website.

- 35 26 October 2022). “Health and Safety Executive Annual Report and Accounts 2021/22 HC 424”. Health and Safety Executive.

- 36 “Conviction history register”, Health and Safety Executive website.

- 37 February 2023). “HSE under pressure: A perfect storm Prospect union’s report on the long term causes and latent factors”. Prospect union.

- 38 Ibid. 5

- 39 Ibid 17

- 40 29 November 2020). “Technology managing people: The worker experience”. Trades Union Congress.

- 41 O’Connor, S. (February 8 2013). “Amazon unpacked”. Financial Times.

- 42 Morgan, K; Nolan, D. (30 January 2023). “How worker surveillance is backfiring on employers”. BBC website.

- 43 Cantwell-Corn, A. (21 April 2023). “Our Data Stories”. Connected by Data.

- 44 Shah, K; Tomlinson, D. (September 2021). “Work experiences - Changes in the subjective experience of work”. Resolution Foundation.

- 45 (December 2021). “Preparing for a post-Covid future: Experiences and attitudes to work”. Unite Research.

Overwork is consistently identified as one of the most common health and safety hazards by union accredited safety representatives. In the TUC’s 2021 survey, 35 per cent of safety reps identified it as a problem in their workplace. In our 2023 survey, 42 per cent identified overwork as a top concern, with 34 per cent per cent also citing long hours. Stress is consistently the most commonly cited workplace hazard, with workload, work intensity and working hours generally understood to be major contributing factors to work-related stress.

In the seventeen years that the TUC has conducted this survey, there has been a general trend: a fall in the occurrence of physical hazards, for example falls from height or exposure to toxic chemicals, replaced by a rise in the risk of psychological and behavioural hazards.

Stress, overwork, and long hours reported as a common hazard by union safety reps:

|

Hazard |

2023 |

2021 |

2018 |

2016 |

2014 |

|

Stress |

73 per cent |

70 per cent |

69 per cent |

70 per cent |

67 per cent |

|

Overwork |

42 per cent |

35 per cent |

36 per cent |

40 per cent |

36 per cent |

|

Long hours |

34 per cent |

29 per cent |

29 per cent |

30 per cent |

26 per cent |

Data from TUC Safety Reps Surveys (2014 – 2023)

Overwork, stress and long hours are all more likely to be reported in the voluntary sector, education, health and central government.

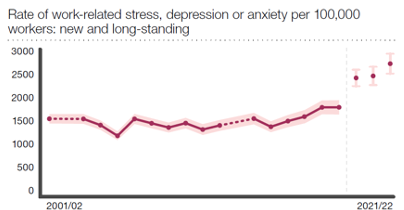

According to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), Britain’s primary workplace safety regulator, cases of work-related stress are rising.

HSE Annual Statistics 2022

Health and safety risks

A range of health effects are associated with intensive working practises, with long hours known to be a major cause of fatigue.

When workers are tired, or under excessive pressure, they are also more likely to suffer injury, or be involved in an accident – 20 per cent of all serious accidents are a result of fatigue.

Long term-ill health conditions caused by overwork include hypertension and cardiovascular disease, digestive problems, and long-term effects on the immune system, increasing risk of causing autoimmune disease diagnoses. It can even result in death: one study found 745,000 people worldwide die as a result of working long hours. In 2022, a courier tragically died in the run-up to Black Friday after working 14-hour shifts. 47 In 2006, an employer became the first to be prosecuted for such a death, after a driver died after working 76 hours over four days.48

Other forms of work intensification, e.g. targets and fast-paced working can cause other hazards. Reports of Amazon workers being forced to urinate in bottles during shifts 49 as a result of excessive pressure to complete tasks, and lack of breaks means workers can risk developing urinary tract infections and make the workplace unhygienic.

In addition to work-related ill health and injury, an alarming number of suicides are linked to work. Hazards Campaign estimates that there are 650 work-related suicides in Britain every year and that 10 per cent of suicides are work-related.50 The most common causes of work-related suicides are job insecurity, overwork and stress.

Work-related suicide is not recorded or investigated by the HSE. After a suicide occurs, employers are not required to evaluate workplace hazards or modify policies and practices. There is no official workplace investigation conducted following an employee's suicide or suicides. A 2021 report by Professor Sarah Waters and Hilda Palmer recommended suicide be included in the list of work-related deaths that must be reported to the regulator for investigation, and for explicit and enforceable legal requirements that oblige employers to take responsibility for suicide prevention.51

There has been recent attention to work-related suicide following the tragic death of headteacher Ruth Perry. The family of Perry have identified pressure relating to Ofsted inspections as a major causal factor in her suicide, and unions and researchers have suggested the problem is more widespread. Walters and Palmer’s (2021) study found that since 1998, coroners’ inquests into the suicides of at least 10 teachers have heard that they took their own life before or after an Ofsted inspection [insert reference].

The role of union organising

All employers have a duty to manage risk, including risk of adverse effects from overwork. Where an employer recognises a trade union, the union may appoint health and safety representatives who have a legal right to monitor, investigate and inspect working practises for risks and hazards.

Among the legal rights set out under the Safety Reps and Safety Committees Regulations 1977, safety reps have the right to:

- be consulted on risk assessments.

- carry out inspections (this could include inspecting workloads or shift patterns)

- issue Union Improvement Notices

- establish (and attend) safety committees

- see relevant information, for example inspection reports or the accident book.

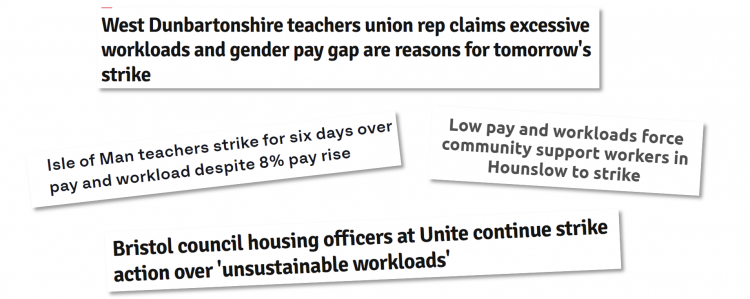

Several unions have taken collective, industrial action in response to punishing workloads, long hours and excessive pressure to complete tasks. These include the first strike by GMB members at an Amazon distribution centre in Britain: while the primary demand related to pay, the workers also walked out because of the long hours expected of them.52

Members of the RMT union on the Caledonian sleeper service took action over fatigue that was risking their safety and the safety of passengers.

After 29 per cent of Unite’s London bus drivers said they had fallen asleep at the wheel, they balloted in their tens of thousands for strike action over fatigue.52 There have similarly been strikes or threats of strike on a range of airlines, predominantly by pilot unions.

Other groups of workers including teachers and paramedics have also cited overwork as a primary concern in strike action.

- 47 Dixon, R; Odeen-Isbister, S. (24 November 2022). “DPD courier found dead after 'working 14-hour shifts 7 days a week' before Black Friday”. The Mirror.

- 48 6 July 2006). “Company fined after driver died at wheel”. Fleet News website.

- 49 Drury, C. (19 July 2019). “Amazon workers ‘forced to urinate in plastic bottles because they cannot go to toilet on shift”. Independent.

- 50 Waters, S. (28 October 2021). “Work-related suicides: the UK’s invisible crisis”. Red Pepper

- 51 Waters & Palmer ‘Work-related suicide: a qualitative analysis of recent cases with recommendations for reform’ (University of Leeds, 2021)

- 52 a b Street, P. “Breaking new ground – the battle for decent pay at Amazon”. Morning Star.

Promote collective bargaining

The case studies demonstrate that unions are already at the forefront tackling work intensification by negotiating with the employers about work organisation.

UNISON has developed a ‘bargaining on workload’ toolkit 54 which includes guidance on how to measure workload intensity and the steps that can be taken to tackle excessive workloads. The guidance includes model surveys to help reps obtain information from the workforce and a model collective agreement that reps can use to negotiate agreements with employers.

BECTU have published guidance 55 on their website, flagging up the key legal rights that can assist reps tackle work intensification problems.

The case study from UCU demonstrates the innovative approach that some unions are taking by developing new workload reps who have the sole focus of tackling work intensification by using existing health and safety rights and negotiating with employers.

The general, broad approach that unions take is to:

- gather information from members via surveys,

- raise the issue with employers,

- negotiate agreements that include safeguards to prevent work intensification,

- involve third party regulators where necessary.

Collective bargaining around work organisation remains the primary tool to tackle work intensification.

But as we flagged above, the decline of collective bargaining has led to work intensification. We need legislative measures to stimulate collective bargaining and make it easier for unions to speak with and represent workers.

To increase collective bargaining our proposals for reform include:

- Unions to have access to workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership and collective bargaining (following the system in place in New Zealand).

- New rights to make it easier for working people to negotiate collectively with their employer, including simplifying the process that workers must follow to have their union recognised by their employer for collective bargaining and enabling unions to scale up bargaining rights in large, multi-site organisations.

- Broadening the scope of collective bargaining rights to include all pay and conditions, including pay and pensions, working time and holidays, equality issues (including maternity and paternity rights), health and safety, grievance and disciplinary processes, training and development, work organisation, including the introduction of new technologies, and the nature and level of staffing.

- The establishment of new bodies for unions and employers to negotiate across sectors, starting with social care– including negotiating around work organisation to prevent work intensification.

Strengthening of Working Time Regulations enforcement

Enforcement of these rights is ineffective. This means one of the key tools to tackle work intensification is being lost. The Health and Safety Executive is responsible for enforcement of the maximum weekly working time limits, night work limits and health assessments for night work. However, their annual report, 56 which contains details of their enforcement activity, makes no mention of any enforcement activity in this area. In its 2022/23 strategy the HSE has committed to ‘Reduce work-related ill health, with a specific focus on mental health and stress.’ This objective must include tackling work intensification which is one of the root causes of stress. HSE could do this by targeted enforcement of the Working Time Regulations.

There is a big gap in the enforcement of Working Time Regulations as HSE is not responsible for the enforcement of time off, rest break entitlements or paid annual leave entitlements. To enforce these important rights an individual worker must bring a claim to an employment tribunal. There are huge delays in the tribunal system.57 Workers should be able to rely on a regulator/labour market inspectorate to enforce these basic workplace rights. The government needs to close this gap and task a labour market enforcement body with responsibility for enforcing these important health and safety rights.

However, instead of moving to improve the enforcement of working time rights, the government has reneged on a promise to create a single enforcement body that would have responsibility for enforcing holiday leave and pay. Despite repeated promises to introduce an employment bill that would enable workers to report employers who failed to provide holiday leave or pay, to an enforcement body, the government has failed to act.

Workers need decent records of working time to ensure they receive adequate rest breaks. Despite recommendations from the LPC for the government to set out explicit record-keeping standards, the government has not done so. Instead, the government is currently proposing to remove retained EU case law around working hours records. This would close one avenue for improved record keeping and send a strong signal to employers that record keeping is unimportant. Labour market inspectors and individuals will rely on employer records to build a case against non-compliant employers. Without these records it will be extremely difficult for workers and enforcement bodies to gather the evidence needed to show that an employer is non-compliant.

Extra bank holidays

The TUC is calling on the government to create four new public holidays. 58

In the EU, every country gets more public holidays than the UK. And the EU average is 12.8 days, which is almost 5 days more than UK workers get.

Romania, Lithuania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Finland and Cyprus top the EU table, with 15 days each – nearly twice as many public holidays as workers in England and Wales.

Beyond Europe, workers in other major economies get more public holidays too. This year there are 17 public holidays in Japan, 12 in Australia and 11 in China and New Zealand.

The TUC is calling for all UK workers to get at least 12 public holidays.

To make sure that no workers miss out, extra public holidays must be reflected in statutory holiday entitlement. And any workers required to work on public holidays should have the right to a pay premium or time off in lieu.

The TUC believes that additional time away from work would help mitigate the impacts of work intensification.

Fix the public sector recruitment and retention crisis

After a decade of government imposed-pay cuts and worsening working conditions, our public sector faces acute staffing shortages in areas such as health, social care and education. Vacancy rates in the NHS currently stands at 9.9%.59 In education, retention rates have reached a historic low - just two-thirds of early-career teachers (67 per cent) remain in the profession after 5 years.60

Low pay, excessive workloads and a lack of flexible work are key drivers of the staffing crisis. Staff shortages put huge strain on those who remain as they try to plug the gaps, fuelling excessive workloads and long-working hours. This undermines the quality of our public services, and leads to high attrition and absenteeism rates, worsening the workload crisis.

To enable employers in the public sector to retain the skilled workforce they need and bring workloads down to a sustainable level, we need government to invest in our public services and their workforce. This investment must include fully-funded pay rises that keep pace with the cost-of-living and improvements to working conditions including a day one right to flexible work.

Investigating work-related suicide

An issue or combination of issues such as job insecurity, discrimination, work stressors and bullying may play their part in people becoming suicidal.61 Work-related suicide is not recorded or investigated by the HSE. As is the case elsewhere in the world, suicide should be included list of work-related deaths in Britain that must be reported to the regulator under reporting requirements. In instances where work-related suicides take place within a workplace, or where evidence suggests a connection to work-related factors, it is crucial these cases are subject to the same level of oversight and regulation as other work-related fatalities. This approach would ensure suicides receive the necessary attention, and enables the collection of vital data to monitor patterns of work-related suicides. Such data would also serve as a foundation for implementing evidence-based preventative measures.

Make flexible working a genuine legal right from the first day in a job

Unions negotiate policies which help workers to work flexibly, helping them to balance their paid work alongside other commitments and wider needs. Unions play a key role by negotiating safeguards to ensure that working from home doesn’t lead to increased work intensification. For example, they ensure that workers are not subject to intrusive monitoring in the home, aren’t working excessive hours and that they are able to take adequate rest breaks from work.

But the government should ensure that all workers can benefit from flexible work and unlock the flexibility in all jobs. Every job can be worked flexibly. There are a range of hours-based and location-based flexibilities to choose from – and there is a flexible option that will work for every type of job. Employers should think upfront about the flexible working options that are available in a role, publish these in all job adverts and give successful applicants a day one right to take it up.

The government should introduce legislation that would give people the right to work flexibly from day one, unless the employer can properly justify why this is not possible. Workers should have the right to appeal any rejections. And there shouldn’t be a limit on how many times you can ask for flexible working arrangements in a year.

Alongside this, it’s vital that the government introduces legislation to facilitate collective bargaining as flexible working will only work where unions can ensure that policies include effective safeguards for workers.

Invest in health and safety regulation

The HSE has suffered enormous funding cuts in the last ten years.62 In 2009/10, the HSE received £231 million from the Government, and in 2019/20, it received just £123 million: a reduction of 54 per cent in ten years. Less funding means fewer inspections: over the same ten-year period, the number fell by 70 per cent, and over a twenty-year period, the number of prosecutions has fallen by 91 per cent. As we’ve shown above, there has been very limited enforcement around the Working Time Regulations. To improve enforcement in this area the HSE needs additional resources.

Local government safety regulation has seen similar levels of cuts as a result of austerity measures hitting council budgets. Long-term, adequate funding of safety regulation is required if we want to keep workplaces safe and ensure employers who break the rules face the necessary consequences.

The government must reverse the cuts, with a long-term investment solution for HSE and local authority environmental health teams to allow for fully-trained inspectors, infrastructure and resources needed to keep workers safe.

A new duty to consult with trade unions about new technologies in the workplace

As we’ve shown above, workplace technology can be a key factor of work intensification.

If new technologies are implemented correctly, they can be used to increase workplace productivity and improve working conditions. For example, where new technologies are introduced, after consultation with unions, workers can share the benefits of increased productivity by working reduced hours or receiving a decent pay rise.

The TUC is concerned that new technologies are being introduced without any consultation with trade unions which means that there is no/little consideration of the safeguards that need to be put in place to prevent new technologies driving work intensification. There is evidence that employers develop new technologies with a view to driving workplace productivity. For example, Amazon have patented a wristband for warehouse workers that could trigger alerts to make them work at a faster pace.63

It’s important that there is a check and balance on these new technologies. Trade unions are critical to ensuring workers have a voice and the power to speak up over how technology is used in their workplace. It’s important that unions are able to negotiate safeguards to ensure new technologies don’t create health and safety risks for workers.

Where trade unions are recognised, they can negotiate agreements on workplace technology and work organisation to ensure that new technology is used to improve the quality of working life – and not lead to the exploitation of working people. The TUC believes the government should create a statutory duty to consult trade unions around the deployment of artificial intelligence and automated decision-making systems in the workplace. This would enable unions to negotiate checks and safeguards to prevent work intensification caused by the introduction of new technologies into the workplace.

Where new technologies are introduced which harvest workforce data, such as a handheld device which measures picking rates, this data should be shared with unions so they can monitor the effects of the new technologies and counter any work intensification. As employers collect and use worker data, workers should have a reciprocal right to collect and use their own data.

Dignity at work and the AI revolution, a TUC Manifesto 64 includes a wide range of proposals to ensure that AI and ADM systems are properly regulated in the workplace, to make sure they don’t have an adverse impact on workers, including work intensification.

A right to disconnect

Technology is increasingly blurring the line between work and our personal lives. The always-on culture of checking emails and taking calls away from work is becoming common place and makes it difficult for workers to disconnect from work, enjoy leisure and family time and ensure that workers have a healthy work-life balance.

A right to disconnect could be a key tool in mitigating the impacts of work intensification, by ensuring workers get a proper rest break away from work and would make sure that work doesn’t encroach upon a worker’s home life.

Unions have developed right to disconnect guidance 65 for their union representatives and negotiated right to disconnect policies with employers.

There should be a statutory right for employees and workers to disconnect from work, to create communication-free time in their lives.

We can look to other European countries for an example of how a right to disconnect could operate.

The Work Foundation, at Lancaster University set out 66 how the right to disconnect legislation works in Ireland:

Ireland

Employees in Ireland were granted the right to disconnect under a new official code of practice, which includes three main clauses;

- The right of an employee to not have to routinely perform work outside their normal working hours.

- The right not to be penalised for refusing to attend to work matters outside of normal working hours.

- The duty to respect another person’s right to disconnect (for example, by not routinely emailing or calling outside normal working hours).

While it will not be an offence to break the code, workers who are asked to regularly work outside agreed hours will be able to refer to it in proceedings before the Labour Court or Workplace Relations Commission (WRC). This new right forms part of the Irish Government’s commitment to create more flexible family-friendly working arrangements, which also includes a consultation on legislating for workers to have the right to request remote working.

The European Parliamentary Research Service set out 67 how the right to disconnect legislation works in France:

France