Work intensification

There are many factors that have contributed to work intensifying.

Decline in collective bargaining

When workers come together to negotiate with their employer, this is known as collective bargaining. Collective bargaining can cover issues like work organisation as well as pay and other key terms and conditions. Work organisation refers to how work is planned, organised and managed within companies and to choices on a range of aspects such as work processes, job design, responsibilities, task allocation, work scheduling, work pace, rules and procedures, and decision-making processes.25 Unions can negotiate the key components of a job to prevent work intensification.

However, industrial changes have combined with anti-union legislation to make it much harder for people to come together in trade unions to speak up together at work. Union coverage in the UK has declined significantly from its peak 40 years ago. In 1979 union density was 54 per cent and collective bargaining coverage was over 70 per cent; in 2022, they were 22.3 per cent and 26.6 percent respectively, with just 13.1 per cent of the private sector protected by a collective agreement.26 Over this period the scope of the bargaining agenda has narrowed significantly - by 2011 pay was the only issue still covered in a majority of collective agreements.27

Because of this, there is less union negotiation around work organisation, resulting in work intensification.

Changes to industrial organisation and management practices over the last few decades

The authors of Working Still Harder28 suggest that ‘outsourcing, subcontracting, joint ventures, and long-term contractual arrangements across value chains—and in the parallel spread of new management practices with associated reorganization of work’ could also be a cause of work intensification.

This is also confirmed in a report on outsourcing, “Outsourcing the cuts: pay and employment effects of contracting out, that was commissioned by UNISON.

This report found that the intense pressure to meet key performance indicators and targets increases work intensity for staff while decreasing the level of autonomy and control they have over their work. A paper from ACAS cites a number of studies suggesting that one result of outsourcing has been the “increased propensity to manage workers by results” and the way in which this is done can lead to lower levels of job satisfaction, higher stress and higher turnover. In turn this can be compounded by the lack of employee influence over “the pace of work and the targets to be met”, which is ultimately determined by the contracting authority, not the worker’s direct employer. While working to demanding performance objectives has become a common feature across the private sector since the 1980s and more recently across the public sector, some studies show that this is particularly intense on outsourced contracts.

Working Still Harder also points out that work intensification may be a consequence of the closer control and discipline afforded by modern forms of management, including:

- Just In Time (JIT) and Total Quality Management (TQM) practices that originated in Japan

- lean production systems

- high-performance work practices including teamwork

- and management through target-setting. Target-setting is assumed to be a key part of efficient management.

Meeting customer expectations

Industrial and cultural change have meant that customers expect prompt delivery of goods and services. The emergence of the gig economy and technological changes have facilitated this. But increased customer expectations have contributed towards work intensification. This is confirmed in the recent Resolution Foundation report, which states “it is ‘clients or customers’, though, that have become the most-cited determinant of how hard people work, with 59 per cent of employees reporting that they mattered in 2017, up from 37 per cent in 1986.”

Staff shortages, redundancies, reduced workforces

Unions have reported 29 that staff shortages caused by a lack of public sector funding and redundancies has led to work intensification, with workers who remain in the organisation picking up the work that still needs to be done.

Austerity policies throughout the last decade have meant many job losses and organisational change in the public sector.30 Professor Les Worral points out that since the 2010 election, the public sector has been the focus of a sustained ideological attack with the sector being subjected to waves of destabilising change: over 631,000 public sector jobs have disappeared at a time when the demands on the sector have clearly increased. There is clear evidence that cost-reduction driven organisational change had led to considerable work intensification and extensification in the public sector. Public sector managers reported that the pace of work, the volume of work and the pressure put upon them to work longer hours to cope with more burdensome volumes of work had all increased. The effect of redundancy and delayering had been to increase role overload in the public sector. Significant proportions of public sector managers reported that working long hours was having a very negative effect on their health, their wellbeing and on their non-working lives.

The case study from the RCM below clearly shows the impact of staff shortages on work intensification.

RCM work intensification case study

NHS employees in England are invited to participate in the annual NHS staff survey. 2022 saw a response rate of 46 per cent, with 636,34831 staff responding.

This revealed that the levels of work intensification for midwives have become intolerable.

Only 7.4%32 per cent of midwives said they had enough staff to provide a safe service. 58.3% per cent of staff are exhausted and regularly feel burnt out because of their workload. 62.8% 33 per cent of midwife respondents said they have felt unwell due to work-related stress.

This is an unsustainable situation impacting upon an already depleted workforce. RCM reports that England has seen midwife numbers plummet by around 600 34 over the past year 2021/2022 on top of an existing and longstanding shortage of over 2000 midwives. RCM analysis of new figures from NHS Digital show that this drop has affected every English region.

One example of significant change, that has lead to work intensification, is the role of midwives in providing neo natal transitional care. On the post-natal wards care of the newborn, who may require intra venous drug therapies and constant observation is performed by midwives, increasing their workload. A 28 bed post-natal ward with 28 cots has a bed occupancy of 56 but invariably staffing levels do not reflect this. Midwife shortages are a significant driver of work intensification. In many units safe levels of staffing are not being met. This leaves those on duty dealing with the workload of many.

Community midwives traditionally provide a 24 hour on-call service but for a number of years have been called into the acute hospital settings at night to make up staff numbers. This impacts upon community staffing levels the following day when the midwives try to catch up on sleep, often needing to work part of the following day to cover clinics – this is unsustainable and affecting health and wellbeing of midwives and support workers. More recently hospital midwives who have not traditionally worked on-call have also been expected to work on-call on non-working days to cover shortages on labour ward, this impacts further on workloads and the health and safety of staff.

The RCM is tackling work intensification by engaging and negotiating with employers to bring in different shift patterns which would help meet staff shortages, help midwives with their work/life balance and alleviate work intensification issues. For example, twilight shifts when midwives would work between 8pm-12am instead of longer shifts.

The RCM has refreshed its 2016 campaign ‘Caring for You’ – which challenges employers to tackle the drivers of work intensification and ensure that they are complying with statutory health and safety requirements.

The RCM has rewritten their Caring for You Charter with 6 key principles:

Culture - Promote a positive, inclusive culture where staff feel valued, respected and invested in, and ensure a safe and effective learning environment for students.

Action - To work in partnership with RCM branch and workforce business partners, to implement bespoke action plans based on local issues, identified by the maternity team.

Responsibility - Implement robust health and safety strategies to prevent damage to staff wellbeing, ensuring zero tolerance of violence and/or aggression. As an employer we are committed to providing a safe and healthy working environment.

Inclusive - Implement actions to address inequality in the workplace, ensure inclusivity and protect staff from bullying, incivility, plus all negative and undermining behaviours.

Nurture - Ensure a positive experience for all new starters, newly qualified and returners to the service. Promote attractive and innovative shift patterns which will be easily accessible to Midwives and MSW’s.

Good to Great - Work in partnership to monitor and evaluate progress in relation to our action plans and the experience of all midwives, MSWs and students, improving and adjusting accordingly.

The employers are asked to sign the charter and commit to negotiations via a working group, which is setup by the Trust and the RCM Branch. They look at each of the six principles over a period of 12 months and agree a plan on how they can improve their services in line with these principles. The group will review employer evidence; what changes are required and how they are established ongoing evaluation working with the Trust values and visions.

Once established and sustained the employer receives the RCM Caring for You award.

Inadequate enforcement of Working Time Regulations

Existing legal requirements under the Working Time Regulations contain important rights for workers which could help safeguard against work intensification and the consequential health and safety risks.

Workers have important rights relating to:

- maximum weekly working time

- night work limits

- health assessments for night work

- time off between shifts

- rest break entitlements

- paid annual leave entitlements.

These vital rights create space for workers to have time away from the workplace. It gives workers time away from the wide range of factors that cause work intensification, such as working at speed, working without proper rest breaks, and having work pace determined by someone else.

Enforcement of these rights is ineffective. This means one of the key tools to tackle work intensification is being lost. The Health and Safety Executive is responsible for enforcement of the maximum weekly working time limits, night work limits and health assessments for night work. However, its annual report, 35 which contains details of their enforcement activity, makes no mention of any enforcement activity in this area. Data on the HSE website 36 also suggest that there have been no convictions in relation to breaches of the Working Time Regulations in the last 10 years. In the last year there has been just one enforcement notice relating to Working Time Regulations. What’s more, the HSE is becoming more and more limited in its capacity due to shrinking resourcing, with its budget cut by almost a half: funding for 2021-22 was 43 per cent down on 2009-10 in real terms. 37

Anxiety about changes to pay and working hours

Research by Tom Hunt and Harry Pickard 38 shows that individuals who are anxious about future changes at work that may reduce their pay and those who are anxious about unexpected changes to their hours of work are more likely to work intensely.

The research shows that if an individual believes they might lose their job in the next year this has zero effect upon an individual's degree of work intensity.

This suggests that individuals may work more intensely as a result of uncertainty about potential changes to specific features of their job (in this instance, pay and working hours), rather than being motivated to work with high intensity because they fear losing their job.

The research also considers the role of personal motivation in determining work intensity by looking at how much influence an individual personally has on how hard they work. The results show those workers who report that they can influence how hard they work to ‘a great deal’ or ‘a fair amount’ do not have a higher degree of work intensity. This further supports the notion that the factors driving work intensity are related to unease about pay and hours, not personal (intrinsic) motivations.

This research is significant as it indicates that workers in precarious employment, who face great uncertainty over income and working hours, are likely to feel more pressure to work intensely.

Use of technology is a key driver of work intensification

TUC polling shows that one third of workers say they have been impacted by the introduction of new technology into their workplace, within the last 12 months.

New technologies can bring significant benefits for both the employer and worker. But the introduction of new technologies need to be managed effectively, and in consultation with the workforce, to ensure that productivity gains deliver improved working conditions and not work intensification.

58 per cent of the workers that the TUC polled say that the new technologies have led them to doing more work in the same amount of time. This is concerning as unions are reporting that technologies are being introduced without the necessary safeguards that would prevent work intensification and the detrimental impact on workers’ health and safety and wellbeing.

New technologies can contribute to work intensification in different ways.

Firstly, computer usage and software that enables workers to utilise efficiency tools such as calendars, emails, task lists etc. – all contribute to making people do more work often without sufficient rest breaks. Research 39 carried out by Francis Green, Alan Felstead, Duncan Gallie and Golo Henseke draws the link between jobs where computer use is essential and high work intensity. They state: “Because of previous evidence about the link between technology and work intensity, we divided the sample into jobs for which the use of a computer was essential (labelled High Computing), and all other jobs (Low Computing). For two out of our three measures of required work effort, High Computing jobs required substantially higher work intensity.”

Secondly, new technologies, workforce data and algorithmic management are driving work intensification by making people work longer and harder.

Our report, ‘Technology managing people: The worker experience’ 40 looks at this in much more depth. But below we pick out some of the key technological drivers of work intensification.

- Digital technologies intensify human activity at work, by increasing the number of tasks completed by people. A BFAWU rep highlighted that “technology is aiding employers with setting targets, like pick rates for example”. Algorithmically set productivity targets can be unrealistic and unsustainable – forcing people to work at high speed. Algorithmic management can also force workers to work faster through constant monitoring, including monitoring the actions they perform and their productivity.

- Worker ratings, often determined by an algorithm, will place immense pressure on workers. Customers are asked to provide ratings on a worker’s performance. This data is then used to create worker ratings which in turn could determine the pay rates and working hours of workers. Because of this, workers are incentivised to work harder and longer to maintain their worker ratings and secure future employment.

- Workplace technologies facilitate constant real-time evaluation of performance. Sarah O’Connor in the Financial Times 41 highlighted that handheld satnav computers are used to give warehouse staff directions on where to walk next and what to pick up when they get there and also to measure a worker’s productivity, the data then being fed back to the employer.

- Workplace monitoring and surveillance can also lead to work intensification as workers fear being sanctioned for spending time away from work. For example, with the increase in working from home, more employers are using software to monitor workers’ whereabouts.42 Some monitoring programs record keystrokes or track computer activity by taking periodic screenshots. Other software records calls or meetings, even accessing employees’ webcams. Some programmes even enable full remote access to workers’ systems.

- Automated decision-making systems can take over the control of work (e.g. content, pace, schedule) through, for example, worker direction, and little will be left to be decided by the worker. Loss of autonomy and job control – as we can see from the NASUWT case study below – can be a key driver of work intensification.

- Portable digital devices are leading to a blurring of work/home boundaries. As we flagged above, our recent polling found that 36 per cent of workers are spending more time outside of contracted hours reading, sending, and answering emails. This leads to working time encroaching on a person’s right to private and family life. The extension of the workday into people’s private lives is an indication that work is intensifying.

A case study from campaign group Connected by Data 43 demonstrates how technology can drive work intensification.

Amazon’s technologically intensive business practices have coined the term the ‘Amazonian Era’.

In the context of the first industrial dispute involving the company in the UK, warehouse worker Garfield Hylton talks about how the company’s use of algorithmic management affects his health and wellbeing.

Garfield Hylton, 59, is a Universal Receiver for Amazon. He has worked at the fulfilment centre in Coventry for almost 5 years.

Amazon gathers data from handheld scanners, which are used to scan an item every time it moves in the logistical process. As well as tracking the items, the data is used for performance management. It collects data to assess against a target ‘rate’ of scans, and to monitor how much workers are considered to be Time Off Task (TOT).

“When we execute an action, it registers as being completed, but if our performance slumps in idle time or Time Off Task the management will ask us why that’s happened,” Garfield says.

However, he adds, “TOT often happens due to system error. The problems normally are things that don't scan, there isn't any work at your station, or you have issues with your station. The system doesn't always recognise this context. I have learnt to keep an extensive log of where I go and what I do in case I get asked why I’ve had a spike.”

As there is no appreciation of context by the software, the lack of discretion can lead to punitive and inappropriate outcomes. The algorithm does not factor in for differences such as illnesses, abilities, personal circumstances or age.

Even small periods of TOT can damage a worker’s performance rate. Garfield, who has diabetes, says that even getting to a toilet in the giant warehouse can cause a spike in your TOT.

“If you have an idle time of an hour because you go to the loo three times in a 10 hour shift for a bodily function you’ll be called in for a conversation about why you’ve had that many spikes.

Ultimately we get on with it but it’s stressful having to constantly prove that you’re not making errors. You shouldn’t have to do that at work.”

Though workers are assessed against a target, they are not told what that target is. The opaque target drives workers to compete with each other to ensure their performance rate is in the top 95 per cent. Every day, workers who are in the bottom 5 per cent must meet with management. If a worker is subject to five meetings, they can be dismissed.

“Your performance is assessed throughout your entire shift, managers are constantly scanning your rate throughout the day,” Garfield says, adding that “it’s really about greed, they’re constantly cracking the whip. New workers have a speed mindset because they’re told that they will be considered for a permanent contract if they work the fastest rate, so they’re being made to work their socks off.”

Appearing at the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Select Committee in November 2022, Brian Palmer, Amazon’s EU Head of Public Policy maintained that data gathering is “not primarily or even secondarily to identify underperformers” for disciplinary or performance management purposes, and was focused on worker safety and logistical accuracy.

Following these statements, law firm Foxglove submitted a supplemental briefing to the committee in December 2022. Foxglove stated that Mr Palmer’s statements were “misleading at best – and at worst, deceptive.” Drawing on internal company documents made available via legal proceedings in the USA, Foxglove demonstrated that Amazon managers are in fact instructed to identify “top offenders”, with documents detailing the subsequent disciplinary and termination processes.

Foxglove stated that if the same or similar practise was carried out in the UK it would “likely violate UK employment law – because workers are being held to a relative standard to keep their jobs, rather than an objective and reasonable one. The practice may also raise issues under discrimination law”.

There is not yet transparency into Amazon’s policies and practises in the UK, though worker testimony and other evidence suggests a similar approach as in the USA.

Garfield talked about the effects of work intensification:

“I’m hanging in there to support my colleagues but I’m realising I’m coming to the end of my tether. I can feel my joints seizing up and I have a bad left hand from work. I’m on unpaid leave at the moment, but then you come into work where you're constantly pressurised and where management is unsupportive, it definitely knocks your resilience down a notch.”

Declining worker autonomy

Resolution Foundation research 44 highlights declining worker autonomy as another factor causing work intensification.

Its research shows that fewer employees report that their “own discretion” determines how hard they work even though the workforce has become more highly educated and more likely to work in “professional” jobs over the period. In 1992, 71 per cent of employees reported having “a great deal” of control over how hard they worked; by 2017 this share had fallen to 46 per cent.

Put simply, this suggests that work organisation, including productivity targets, pace of work and how work is done, is increasingly being decided by employers. Where individual workers and unions are not involved in discussions around work organisation it is more likely that workers will experience work intensification.

Findings from Unite the union’s large scale membership survey confirm this.

Unite survey 45 highlights unpaid overtime, work-related stress and lack of influence over the pace of work

The findings of the first Unite all members’ survey, published in December 2021, present a significant picture of members’ experiences of and attitudes to work. It was an online survey with 31,700 completed responses across all Unite sectors and regions.

The survey findings suggest that work intensification could be causing serious issues for Unite members.

Unpaid overtime

Just under a quarter (24 per cent) of respondents reported experiencing ‘unpaid overtime’ suggesting high workloads. This was particularly an issue in the Finance & Legal, Community, Youth Workers & Not for Profit, and Health sectors.

Work related stress

‘Work related mental health and stress’ was cited as the biggest concern at work by 7 per cent of respondents (although it also featured in respondents’ second and third concerns). However, when asked to identify issues they had experienced in the last 12 months, ‘work related stress’ was by far the most cited issue (by 60 per cent of respondents). It was the most cited issue experienced across all sectors, but was most acute in public services sectors such as Health (71 per cent), Community, Youth Workers & Not for Profit (71 per cent) and Education (69 per cent). This is in line with the findings of a survey of Unite Workplace Representatives published in April 2021 which found that 83 per cent of reps were dealing with an increase in members reporting mental health-related problems, a huge 18-point increase from the 65 per cent reported in 2020.

Changes to work imposed without consent

Unite members reported that changes to work imposed without consent also featured as a part of members’ work experiences. 21 per cent of respondents said that this had occurred in respect of ‘restructure and reorganisation of my job’, 15 per cent in respect of ‘changes to my contract and terms or conditions’, and 13 per cent in respect of ‘changes to my working time’. Changes to working time imposed without consent suggest that Unite members may be facing less favourable working time to pick up additional workloads.

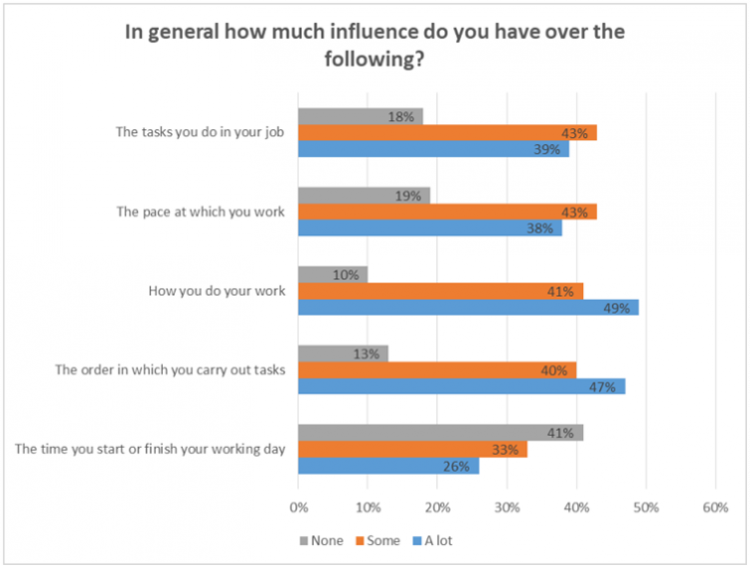

Lack of influence over elements of work

The table below, taken from the survey findings, reveals some factors which may be driving work intensification for Unite members. Only 38 per cent of Unite members felt they had a lot of say in determining the pace at which they worked, which suggests for a large number of Unite members they may be working at a pace which is too intense for them. Only 26 per cent of Unite members felt that they had a lot of say over the time they started or finished the working day. This suggests that workload issues may be determining the start/finish time for a large number of Unite members. We know that high workloads are associated with work intensification.

- 25 25 May 2023). “Work organisation”. Eurofound Website.

- 26 24 May 2023). “Trade union statistics 2022”. Department for Business and Trade.

- 27 3 September 2019). “A stronger voice for workers How collective bargaining can deliver a better deal at work”. Trades Union Congress

- 28 Ibid. 17

- 29 11 May 2020). “Many of my colleagues have been made redundant and the rest of us are expected to cover lots of their work, is there anything I can do as I feel I can’t cope?”. Prospect union website.

- 30 Worrall, L. (23 July 2013). “Austerity’s assault on the public sector has had tremendous impact on managers’ physical and psychological wellbeing”. LSE blog.

- 31 March 2023). “NHS Staff Survey 2022 National results briefing”. Survey Coordination Centre, NHS.

- 32 “NHS England survey results 2022”. Royal College of Midwives website.

- 33 National NHS Staff Survey 2022 - Detailed Spreadsheets

- 34 1 July 2022). “Drop in midwife numbers accelerates”. Royal College of Midwives website.

- 35 26 October 2022). “Health and Safety Executive Annual Report and Accounts 2021/22 HC 424”. Health and Safety Executive.

- 36 “Conviction history register”, Health and Safety Executive website.

- 37 February 2023). “HSE under pressure: A perfect storm Prospect union’s report on the long term causes and latent factors”. Prospect union.

- 38 Ibid. 5

- 39 Ibid 17

- 40 29 November 2020). “Technology managing people: The worker experience”. Trades Union Congress.

- 41 O’Connor, S. (February 8 2013). “Amazon unpacked”. Financial Times.

- 42 Morgan, K; Nolan, D. (30 January 2023). “How worker surveillance is backfiring on employers”. BBC website.

- 43 Cantwell-Corn, A. (21 April 2023). “Our Data Stories”. Connected by Data.

- 44 Shah, K; Tomlinson, D. (September 2021). “Work experiences - Changes in the subjective experience of work”. Resolution Foundation.

- 45 (December 2021). “Preparing for a post-Covid future: Experiences and attitudes to work”. Unite Research.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox