Work intensification

There is lots of evidence to show that work is intensifying.

TUC polling

Polling 15 commissioned by the TUC revealed that:

- 61 per cent of workers feel exhausted at the end of most working days.

- 55 per cent of workers feel that work is getting more intense and demanding, over time.

We also asked workers what work-related actions they are doing more of, outside of contractual hours, compared to 12 months ago. The findings showed that:

- 36 per cent of workers are spending more time outside of contracted hours reading, sending and answering emails.

- 32 per cent of workers are spending more time outside of contracted hours, doing core work activities.

This increase in work-related actions outside of contractual hours is indicative of work intensification. High workloads which are not achievable during contractual hours, spill over into workers’ private lives, meaning they are undertaking work in the evenings, whilst at home.

In addition, union health and safety representatives told us that factors relating to work intensification are some of the most common workplace hazards they encounter 16 :

- 59 per cent identified stress as one of the most common hazards.

- 45 per cents said bullying and harassment by management and colleagues was a common concern in their workplace.

- 28 per cent said overwork specifically was a safety concern widespread among their members.

Recent academic research

A number of research reports, published over the last couple of years, confirm that work is intensifying. These are discussed below.

Working still harder

The Skills and Employment Survey (SES) is a consistent series of nationally representative sample surveys of employed individuals in Britain, conducted at five- or six-year intervals. The surveys ask workers about their perceptions of work intensification. Respondents are asked how much they agree or disagree with the statement, “My job requires that I work very hard”. The survey also asks respondents to rate on a scale “How often does your work involve working at very high speed” and “How often does your work involve working to tight deadlines”.

Analysis of this large dataset 17 confirms earlier studies that had reported a rapid intensification of work in Britain in the first part of the 1990s followed by a plateau of flat or declining work intensity in the latter part of that decade. The story from 2001 on is one of renewed work intensification. Between 2001 and 2006, two out of the three indicators of work intensification (mentioned above) rose, as did the overall index; from 2006 until 2017 all three indicators and the overall index increased.

Most notably, the proportion of workers in jobs where it was required to work at ‘very high speed’ for most or all of the time rose by 4 percentage points to 31 percent in 2017.18

Work experiences: Changes in the subjective experience of work

Resolution Foundation analysis 19 shows how the pace of work has increased in Great Britain since the early 1990s across several different metrics.

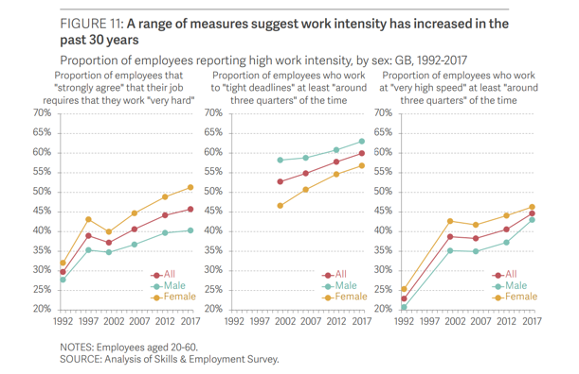

The graph below shows the share of employees who “strongly agree” that their job requires that they work “very hard” has increased from 30 per cent in 1992 to 46 per cent in 2017. The share of employees who work to “tight deadlines” for at least “around three quarters” of the time has increased from 53 per cent to 60 per cent. The share of employees who report they work at “very high speed” for at least “around three quarters” of the time has almost doubled from 23 per cent to 45 per cent.

The share of employees who report that their work is “always” or “often” stressful has risen from 30 per cent in 1989 to 38 per cent in 2015. Strikingly, the proportion of those who report they are often stressed in skilled manual roles (such as driving or care work) has doubled over the same 26-year period, from 18 per cent to 41 per cent.

These findings demonstrate significant increases in work intensity particularly those working at very high speed and those that strongly agree that their job requires them to work ‘very hard'.

- 15 Nationally representative polling conducted by Thinks Insight & Strategy for TUC. 2,198 workers in England and Wales in August 2022.

- 16 Health and Safety Reps Survey 2023, Trades Union Congress.

- 17 Green, F; Felstead, A; Gallie, D; Henseke, G. (March 2022). “Working Still Harder”. ILR Review, Volume 75, Issue 2

- 18 Green, F; Felstead, A; Gallie, D; Henseke, G. “Work Intensity in Britain: First Findings from the Skills and Employment Survey 2017”.

- 19 Shah, K; Tomlinson, D. (September 2021). “Work experiences: Changes in the subjective experience of work”. The Resolution Foundation.

The Resolution Foundation reports that “the changing composition of the workforce (both in terms of personal characteristics and the occupations and industries in which people work) explains only a small part of these trends, suggesting that something fundamental has changed in the nature of work over the last 30 years.”

Covid-19 and Working from Home Survey

The Covid-19 pandemic and large-scale shift to working from home for some groups of workers also led to work intensifying in some roles. The shift to home working has, in many cases, blurred the boundaries between work and home for many people. This has led to work-related activities seeping into vital rest time, impacting both workers and their families.

A report drawing on the findings from a Covid-19 and Working from Home Survey 20 highlighted that:

“Large numbers experienced increases in volumes of work (32 per cent), intensity of work (38 per cent), pace of work (32 per cent), pressure of work (32 per cent). Variety of work is less than in the office, but skill and personal control over work were greater when WFH. 39 per cent report that managers contact workers for progress reports at least once a day. 45 per cent report that automated systems monitor work activity and 38 per cent that they monitor work rate. 29 per cent reported working extra time in order to complete tasks that could not be completed during their scheduled working time.”

A sizeable minority (29.1 per cent) of survey respondents said they are now expected to work extra time if tasks are not completed in allotted time, a finding that is consistent with the reported increases in the volume and pressure of work.

The study was initiated by authors and the STUC and supported by several trade unions (CWU, Unite the Union, TSSA, Unison, Accord, PCS) and campaign group Hazards.

Concerns about working from home leading to work intensification further strengthens the case for working from home policies to be negotiated with trade unions to ensure safeguards are included. Unions negotiate flexible working policies that ensure that workers, whose roles can be done at home, get the added flexibility and benefits that working from home can bring. Unions will also negotiate safeguards in policies to ensure that working from home doesn’t infringe basic rights such as a right to family life, right to privacy and entitlements to adequate rest breaks.

International comparisons

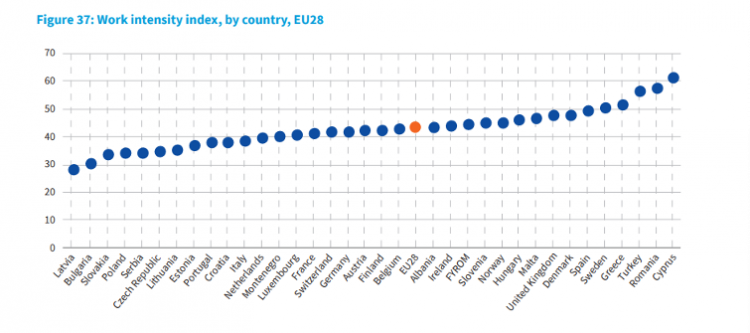

Analysis of work intensity indicators in the European Working Conditions Survey 2015 and the European Social Survey 2010 showed that the United Kingdom ranked highest among the EU28 for the percentage of workers reporting that they work to tight deadlines, second for working very hard and average for working at high speed. 21

How do we compare to our European counterparts?

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox