Making hybrid inclusive

This report was written by Heejung Chung, University of Kent and King’s College London, Shiyu Yuan, University of Kent and Alice Arkwright, TUC.

The Covid-19 lockdowns presented enormous challenges for working people across the country but did open an opportunity to work from home that had been denied to many previously. Since the rise in homeworking, we have seen increasing literature on the benefits and drawbacks of home and hybrid working and the need for other types of flexible working to grow,1 but very little on the experiences of BME workers. This joint research between TUC and University of Kent attempts to plug that gap providing insight on the experiences of home and hybrid working through a diary study of 20 BME hybrid workers over the course of a month. Ahead of this University of Kent analysed Labour Force Survey data on access to flexible working and provided a literature review of existing research in the area.

Our research finds that access to and experiences of home/hybrid are inherently linked to other forms of discrimination at work, in this case workplace racism, and that well-designed hybrid working is essential to avoid exacerbating discrimination and also to promote equality.

Analysis done by University of Kent of 2022 Labour Force Survey data found that certain ethnic groups are less likely to be able to access home or hybrid working. Black (African/Caribbean/Black British), Chinese and other Asian, and to a lesser extent Pakistani and Bangladeshi workers, in particular men from these groups are least likely to be able to work from home. What is more the gap found ‘post-lockdown’ is more evident compared to pre-pandemic data in 2019. The TUC believes this is partly down to occupational and sector segregation as BME workers are overrepresented in roles where work from home 2 is not possible but also experiences of racism in the workplace compounded by flexibility stigma which means BME workers may feel less able to ask and get flexibility.3

In our diary study, participants experiences showed that stigma around home working still exists leading to negative consequences such as micromanagement and monitoring, longer working hours or feeling the need to perform digital presenteeism. In addition, both the stigma and negative consequences of it can be exacerbated for BME workers due to the additional experiences of workplace racism. The diary study revealed the following about the experiences of BME workers who can work from home.

- Home working was really valued by the majority of participants because of improved work-life balance, greater ability to manage caring responsibilities, more time with loved ones, improved productivity and accessibility and the majority indicated they would not take jobs without access to this in the future. This is supported by multiple pieces of research demonstrating the benefits of home working to both workers and employers.4 The TUC believes all workers who can work from home should have access to it and that it, and other forms of flexible working, are essential to achieving equality at work.5 However, the rest of our findings show that employers need to take steps to improve the experiences of home workers and that there will always be people for whom home working does not suit. Some workers will have a preference for the working in the employer’s premises, perhaps because of lack of access to home-working set up, desire to separate work and home life, or to support their mental health.

- Despite the popularity and benefits of home working, experiences of participants showed that stigma against home workers still exists,6 particularly in relation to perceived commitment to work and work ethic. Our participants felt this stigma was intensified or linked to their race, age or disability as well as their home working status. The workers who reported experiencing the least stigmatised views towards home workers all noted that this was due to home/hybrid working being normalised, promoted positively in the organisation and supported and used by their line-managers.

- New forms of monitoring have been introduced due to home working, for example apps/software to log start, finish and break times and excessive messaging. Our participants felt BME colleagues were more likely to be subject to monitoring in comparison to White colleagues, showing how negative practices associated with home working could be applied more heavily to Black workers.7

- The study provides support to the idea 8 that home working has potentially led to people working harder and longer, for example cases of people working late into the evening, missing breaks, working in commuting time, constantly being available or using home working to cope with increasing workloads. Participants shared that this happened due to excessive workloads, availability of phones and laptops at home, but also due to the need to prove their worth due to negative perceptions of home workers. Participants shared that this was heightened for BME workers as negative perceptions of home working exacerbated feelings of insecurity and vulnerability in the workplace caused by workplace racism. Working longer hours or acts of presenteeism could therefore be more common for BME home/hybrid workers as flexibility stigma and racial discrimination intersect.

- Participants shared that working from home provided respite from the racist comments they experienced in workplaces.9 Home working will not resolve workplace racism and is not a replacement for effective anti-racism and inclusion work by employers. Instead, this highlights an important but often missing part of discussion about the benefits of office working, which is whether BME workers feel safe and included in working environments, both in workplaces and when working from home. Further, we need to consider what kind of workplace we are asking BME workers to return to and whether all workers are included in socialising and collaboration which are highlighted as key benefits of going into the workplace. Home workers will also experience workplace racism and exclusion, for example participants shared experiences of not being invited to meetings, being spoken over in online meetings, having their seniority questioned and being excluded from decision making. However, online tools had allowed BME workers to create wider networks across geographically dispersed larger organisations, connecting them to other BME workers.

Given our research found that flexibility stigma and associated downsides of hybrid working can be disproportionately felt by BME workers, it is essential that employers take action to ensure that hybrid working is implemented in inclusive ways and address workplace racism. Home working supports equality, provides benefits for employers and many workers have strong preference for it. Therefore, the solution is not to prevent home working but to have good policies, practices and cultures to support its use. Employers should focus on ways to normalise flexible working, making it the default way of working across all jobs, provide appropriate training/guidance and conduct equality monitoring. Employers must ensure that whilst flexibility is normalised, home working should still be voluntary and not forced. They must also take steps to address workplace racism, including establishing comprehensive monitoring systems and strong policies for dealing with racism at work. A full set of recommendations for employers and unions can be found at the end of the report.

- 1 For example, Chung, H., Birkett, H., Forbes, S., & Seo, H. (2021). Covid-19, Flexible Working, and Implications for Gender Equality in the United Kingdom. Gender & Society, 35(2), 218-232. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211001304

- 2 Taken by comparing ONS data of Characteristics of homeworkers, Great Britain: September 2022 to January 2023 https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmen… with TUC analysis of BME workers occupational representation https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-moni…

- 3 Timewise. (2023). 1 in 2 UK workers would consider asking for flex on day one of a new job. London: Timewise; Williams, J., Blair-Loy, M., & Berdahl, J. L. (2013). Cultural schemas, social class, and the flexibility stigma. Journal of Social Issues, 69(2), 209-234.

- 4 Chung H (2022) The Flexibility Paradox: Why flexible working can lead to (self-)exploitation. Bristol: Policy Press, Chung H, Seo H, Forbes S, et al. (2020) Working from home during the COVID-19 lockdown: Changing preferences and the future of work.

- 5 TUC. (2021). The future of flexible working. London: UK Trades Union Congress; Chung H, Birkett H, Forbes S, et al. (2021) Covid-19, Flexible Working, and Implications for Gender Equality in the United Kingdom. Gender & Society 35(2): 218-232

- 6 Chung H (2020) Gender, flexibility stigma, and the perceived negative consequences of flexible working in the UK. Social Indicators Research 151(2): 521-545, Chung H and Seo H (2023) Flexibility stigma - how national contexts can shift the extent to which flexible workers are penalised. TransEuroWorks Working Paper Series 3/2023.

- 7 The TUC uses the term ‘Black workers’ to indicate people of colour with a shared history. ‘Black’ is used in a broad political and inclusive sense to describe people in the UK who have suffered from colonialism and enslavement in the past and continue to experience racism and diminished opportunities.

- 8 Chung, H. (2022). The Flexibility Paradox: Why flexible working can lead to (self-)exploitation. Policy Press.

- 9 Similar finding was found in Future Form. (2022). Levelling the playing field in the hybrid workplace online: Future Forum/Slack.

Introduction

Genuine flexible working can be a win-win arrangement for both workers and employers. It can allow people to balance their work and home lives, is important in promoting equality at work and can lead to improved productivity, recruitment and retention of workers for employers.10

The Covid-19 lockdowns presented enormous challenges for working people across the country but did open up an opportunity to work from home that had been denied to many previously.11 Enforced home working during lockdown periods has now been followed by adoption of hybrid working in many workplaces. In Q4 2019, 6.8 per cent of the population said they mostly worked from home, rising to 22.4 per cent in Q4 202112 and dropping slightly to 21.1 per cent in Q2 2023.13

We know home working is popular amongst working people. TUC research in 2021 found that more than nine out of ten (91 per cent) of those who worked from home during the pandemic want to spend at least some of the time working remotely.14

The growth in home working has seen benefits for many, making it easier to balance work and care, reducing commuting time, spending more time with family, removing barriers to work for disabled workers, older workers and workers with caring responsibilities,15 giving working people more time for learning and helping to improve productivity. Yet it has also raised challenges, with potential for longer working hours, blurred boundaries between home and work life and poor working environments.16

As workers and employers adjust to new working arrangements, we have seen increasing literature on how to introduce hybrid working successfully but also pressures from some employers and government to push people back to the office, despite overall preferences to have access to home working.17 However, there has been little research on BME workers’ experiences of flexible working in general including home and hybrid working. Therefore, the TUC has worked with the University of Kent to undertake research into Black workers’ access to and experiences of flexible working. This report looks at hybrid and home working. We believe this is important to ensure that flexible working and by extension workplaces are more inclusive for Black workers.

Methodology

This research has been undertaken in partnership with the University of Kent. We wanted to understand Black workers’ experiences of home and hybrid working, to develop recommendations for practical actions that unions and employers could take to improve experiences of hybrid working and implemented it in inclusive ways. We therefore took a qualitative approach, running an online diary study with Black workers.

We ran an initial recruitment survey for people to an express an interest in taking part, advertised through TUC affiliated unions, organisations that campaign on flexible working and social media. We received 102 responses and from that 27 people were selected to take part in interviews to assess their eligibility for the research. 24 people were chosen to take part in the research of which 20 completed the research project.

The research project ran from 5 June 2023 to 5 July 2023 and participants were asked to upload responses to 12 tasks over the course of the month relating to hybrid working. The responses were uploaded to a mobile app in the form of video, notes or pictures. Throughout the month more information was gained through chat functions in the app.

Information on participants

Of the 20 that took part:

- Six were men and 14 women;

- Two were based in the East of England, six in London, one in the North West, two in Scotland, three in the South West, one in Wales, one in the West Midlands and four in the Yorkshire and Humber;

- All participants identified as BME. Seven identified as Asian/Asian British, six as Black/Black British, six as Mixed Race and one from another ethnic group;

- Nine participants identified as disabled; and

- Eight participants had children under 18 and four had other caring responsibilities.

Their employment arrangements were as follows:

- All were employed full time.

- 18 had permanent contracts and two were on fixed term contracts.

- All worked in organisations that employed over 250 people.

- All but one were a member of a union.

- One worked in accounting and financial management, two in charity/third sector, one in education, four in financial services and insurance, two in health and social work, eight in public administration, defence and social security, one in service centre and one in utilities.

- Eight had line management responsibilities.

Their flexible working arrangements were as follows.

- All stated they worked in a hybrid pattern and three stated they also worked compressed hours, 14 had flexi-time arrangements and one had a mutually agreed predictable shifts.

- Hybrid patterns varied. Six spent 80 per cent or more of their time at home, four said they worked 60 per cent of time at home, one worked 50 per cent at home, three spent 40 per cent of their time at home, one spent 25 per cent of time at home and five said their hybrid pattern varied and they were free to choose where they worked.

- 19 participants had a workplace arrangement/policy that allowed them their working pattern and of this 19, five had also requested additional or different flexibility. One participant’s flexibility was due to an individual contractual request.

- Of the 19 that had a workplace policy, 16 said this had been introduced as a result of Covid-19.

In addition to the diary study, the University of Kent produced a literature review summarising existing material in connection to BME workers experiences of flexible working and analysed data from Q2 2019 and 2022 of the Labour Force Survey, published by the Office for National Statistics.

Limits of the research

It should be noted that those who took part in this research were self-selecting. Those keen to speak to a researcher tend not to be those with the most difficult experiences. In addition, as participants were self-selecting and recruited mainly through TUC affiliated unions, employees in the public sector, in particular public administration, and union members were overrepresented in the study.

Due to the size of the group taking part and requests for anonymity, we have not provided a descriptor of participants next to quotes unless relevant to the analysis.

BME workers’ access to home working

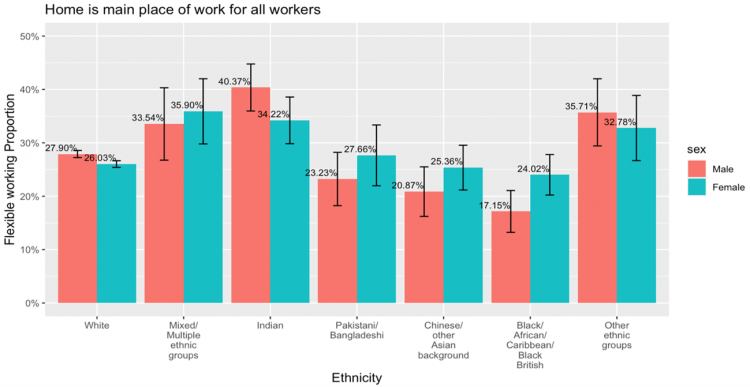

University of Kent’s analysis of Q2 2022 Labour Force Survey data found that when comparing all BME workers to White workers there is no difference to in the percentage of people who have access to home working but that there are differences amongst ethnic group and gender. As Figure 1 shows Black (African/Caribbean/Black British) men (17 per cent), Chinese/other Asian men (21 per cent) and Pakistani/Bangladeshi men (23 per cent) are the least likely to state that home is their main place of work. Amongst women there is a similar pattern as it is Black (24 per cent) and Chinese/other Asian (25 per cent) women who are least likely to report that their home is their main place of work. Across the board, women are slightly less likely to state their main place of work is home compared to men. Although amongst ethnic groups where home working is least reported, (Pakistani/Bangladeshi, or Chinese/other Asian, or Black African, Caribbean, Black British), women are slightly more likely to say they work from home most of the time although the difference is not statistically significant.

- 10 Beauregard, T. A., & Henry, L. C. (2009). Making the link between work-life balance practices and organizational performance. Human resource management review, 19(1), 9-22. , Chung, H. (2022). The Flexibility Paradox: Why flexible working can lead to (self-)exploitation. Policy Press. , Kelliher, C., & de Menezes, L. M. (2019). Flexible Working in Organisations: A Research Overview. Routledge.

- 11Chung, H. (2018). Dualization and the access to occupational family-friendly working-time arrangements across Europe. Social Policy and Administration, 52(2), 491-507. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1111/spol.12379 12 TUC. (2022). Work from Home Day: homeworking has tripled since before the pandemic. London: UK Trades Union Congress.

- 12 TUC. (2022). Work from Home Day: homeworking has tripled since before the pandemic. London: UK Trades Union Congress.

- 13 TUC. (2023). Work Capability Assessment (WCA) Activities and Descriptors consultation. TUC response to the Department for Work and Pensions Consultation. London: UK Trades Union Congress

- 14See also, Buffer. (2021). The state of remote work 2021: Buffer. https://buffer.com/2021-state-of-remote-work (accessed 24th of March 2021), ONS. (2023). Characteristics of homeworkers, Great Britain: September 2022 to January 2023 13 Feb 2023. London: Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmen…

- 15 Chung, H., & Van der Horst, M. (2018). Women’s employment patterns after childbirth and the perceived access to and use of flexitime and teleworking. Human Relations, 71(1), 47-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717713828 , Hoque, K., & Bacon, N. (2022). Working from home and disabled people's employment outcomes. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 60(1), 32-56.

- 16 Chung, H. (2022). The Flexibility Paradox: Why flexible working can lead to (self-)exploitation. Policy Press. , Fan, W., & Moen, P. (2023). Ongoing Remote Work, Returning to Working at Work, or in between during COVID-19: What Promotes Subjective Well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, online first, 00221465221150283.

- 17 Sasso, M. (2023, June 22nd 2023). In returning to the office, one gender is rushing back faster than the other. Fortune Magazine. https://fortune.com/2023/06/22/return-to-office-rto-men-vs-women/

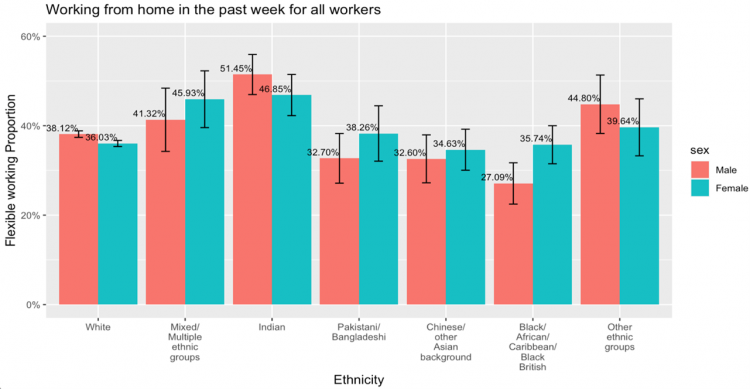

Similar patterns are found when looking at those who have reported working from home at least one day per week (see Figure 2). The percentages are much higher overall, but it is again Black (African/Caribbean/Black British) men (27 per cent) and Chinese/other Asian and Pakistani/Bangladeshi men (33 per cent) who are least likely to be able to access this form of flexibility.

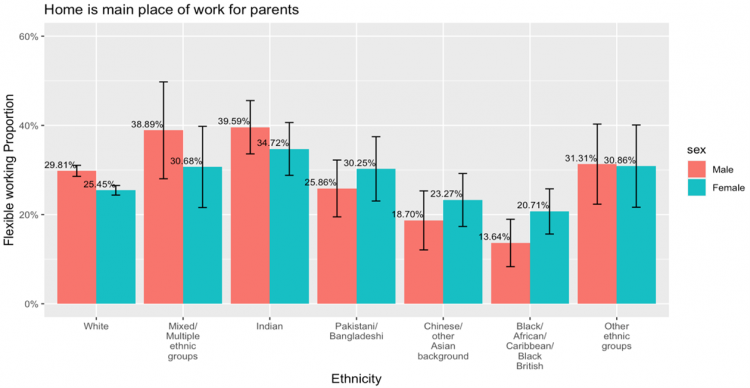

The University of Kent also looked at the data by parental status and found that parents are slightly less likely to report that home is their main place of work compared to the overall population even though we may assume that those with caring responsibilities may need and want flexibility more than those without.18 Again, similar patterns are found with Chinese/Other Asian (19 per cent) and Black (African/Caribbean/Black British) (14 per cent) dads as the groups least likely to report that home is their main place of work. Again, women from these ethnic groups are also the least likely to report home as their main place of work in comparison to mums from other ethnic groups (23 per cent and 21 per cent respectively), as seen in Figure 3.

- 18 Chung, H., Seo, H., Forbes, S., & Birkett, H. (2020). Working from home during the COVID-19 lockdown: Changing preferences and the future of work 29/07/2020. Canterbury, UK: University of Kent. http://wafproject.org/covidwfh/, Lambert, S. J., & Haley‐Lock, A. (2004). The organizational stratification of opportunities for work–life balance: Addressing issues of equality and social justice in the workplace. Community, Work & Family, 7(2), 179-195.

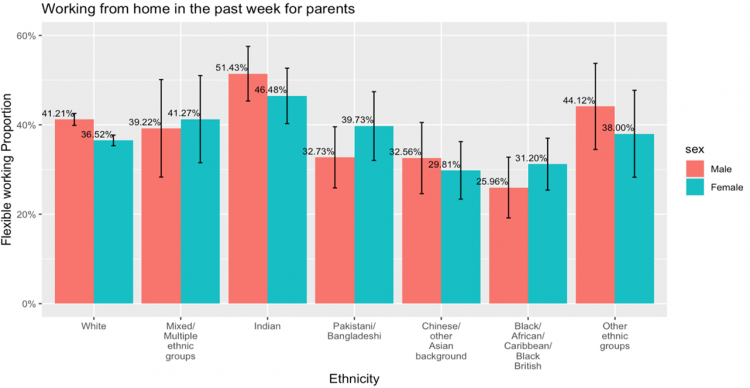

Figure 4 shows similar patterns when looking at parents who have reported working from home at least one day in the last week. Black (African/Caribbean/Black British) mums (31 per cent) and dads (26 per cent), Chinese/other Asian dads (33 per cent) and mums (30 per cent) and Pakistani/Bangladeshi dads (33 per cent) are the least likely to report this.

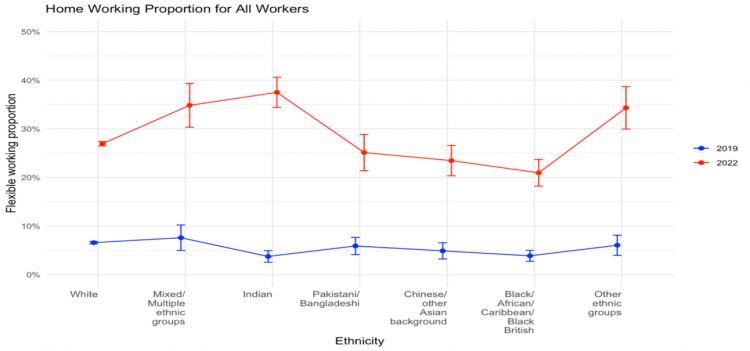

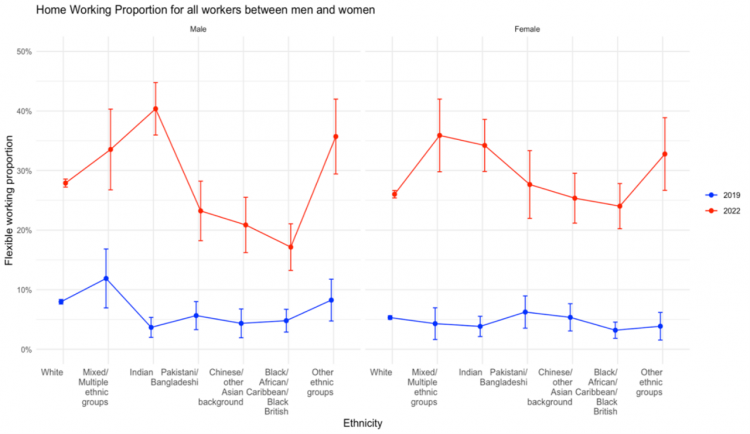

Finally, Figures 5 and 6 show the changes in the proportion of workers working from home as the main place of work for all workers (Figure 5), and men and women separately (Figure 6) in 2022 compared to 2019. Firstly, we can see that there has been a general increase in the number of workers who work from home since the pandemic. However, the rate of increase differs between different ethnic groups – again with Black (African/Caribbean/Black British), Chinese/other Asian, and Pakistani/Bangladeshi workers seeing the slowest increase in the rate of homeworking, compared to other ethnic groups. Figure 6 indicates that this was especially visible amongst men. The pandemic seems to have led to a larger gap between ethnic groups with regards to their homeworking practices.

The data therefore shows that the rise in homeworking practices was not equal and there are some ethnic groups consistently losing out on access to home and hybrid working - Black (African/Caribbean/Black British), Chinese and other Asian, and to a lesser extent Pakistani and Bangladeshi, and in particular men from these ethnic groups. The TUC believes this is partly down to occupational segregation. BME workers are overrepresented in three of the four occupations with the lowest rates of home or hybrid working: elementary occupations, sales and custom service occupations and personal service (sales and custom service).19 However, further analysis is needed to understand this by different ethnic group.

In addition, the University of Kent also conducted the same analysis where they controlled for a number of different factors including size and sector of company and occupation, and similar results were found meaning it is likely that this difference in access to home working is also down to workplace racism. BME workers may feel less able to ask for flexibility potentially due to the fear of negative career consequences associated with flexible working 20 or other negative repercussions. Timewise research 21 also found that 61 per cent of BME workers said they would consider making a flexible working request from day one in a new job compared to 48 per cent of White workers, with regards to the changes made in the new day one right to request legislation.22 Timewise state this may be indicative of BME people currently feeling unable to speak to managers about adjusting their working patterns. In fact, over a third (37 per cent) of BME workers said they would not feel comfortable talking to their current employers about changing their working pattern compared to 28 per cent of White workers. The myriad of structural and institutional racism that BME workers face for example being more likely to be in insecure work,23 more likely to be unemployed,23 more likely to face disciplinary procedures,25 more likely to be overlooked for promotion 26 and face more scrutiny at work 27 means it is likely that BME workers will feel unable to ‘rock the boat’ by asking for flexible working which is still seen as an awkward request by many employers.

Conclusion

As seen above both occupational segregation and racism in the labour market impact BME workers access to home working. Data reveals there are still stark differences in access between ethnic groups and whilst home working has grown overall, the difference between ethnic groups widened over the pandemic. A request-based system will often mean that those with protected characteristics lose out due to the discrimination they already experience as they are more likely to lack bargaining power at work. Flexible working must therefore be normalised as the default way of working for everyone, not just in roles in that can be done from home, and the structural and institutional racism that causes unequal power relationships addressed.

Existing research on BME workers experiences of hybrid working

University of Kent conducted a literature review of existing research on BME workers experiences of home and hybrid working, which found significant gaps in research with what does exists being largely US based. What does exist has looked at experiences of racism, belonging and exclusion, impacts on career, monitoring and surveillance and wellbeing and future preferences. This section summarises existing research.

Experiences of racism whilst working from home

The TUC report Still Rigged outlines examples of structural, institutional, and everyday racism that Black workers experience across the economy.28 There is some evidence to suggest that home working changes people’s experiences of everyday racism, for example a survey of US adults in 2022 found that 47 per cent of BME women when asked about their anxieties around returning to work were worried about dressing for work29 and some qualitative evidence on a reduction in experiences microaggressions whilst working at home.30 Concerningly though, there is evidence around increased experiences of harassment, for example a study of tech workers in the US showed an increase of harassment, including racial harassment whilst working from home 31 and the section below shows how exclusion continues.

Sense of belonging and exclusion

Not surprisingly, research has shown a mixed picture of people’s experiences, with home working providing the potential for increased sense of belonging but also the continuation of exclusion. A survey of 5,000 US workers who work from home/remotely found that Black workers had the biggest increase in sense of belonging comparing May 2021 and August 2022, from 24.2 per cent to 31.4 per cent and for Hispanic and Latinx workers this had increased from 27.3 per cent to 30.2 per cent. There was also a significant increase in the proportion of Black workers who agreed with the statement “I value the relationships I have with my colleagues” over the period where home and hybrid working became more common from 69 per cent in May 2021 to 81 per cent by November 2021.32

Contrastingly, a survey carried about by Microsoft found that Black and Latino workers in the U.S. reported more difficulties building relationships with their direct team (19 and 18 percent, respectively, compared to the 12 per cent national average) and feeling included (21 and 28 per cent, compared to a 20 per cent national average).33

Impact on careers

One of the biggest barriers in taking up flexible working arrangements is workers’ fear of potential negative career consequences due to flexible working.34 This may be especially true for BME workers who may already experience discrimination such as questions against their work commitment, motivation and productivity. In fact, a survey in the UK by Fawcett 35 found that 52 per cent of BME people agreed with the statement “I would like greater flexibility in my work but am worried about the implications for my career” compared to 40 per cent of White respondents. This potentially highlights the higher standard to which BME workers are held to progress at work, and the negative ways flexible working can be perceived by employers are compounded for BME people due to additional experiences of racism. In the same survey, 35 per cent BME respondents agreed that “working flexibly has a negative impact on promotion and pay”, compared to 27 per cent of White people.

On the other hand, homeworking may provide BME workers more opportunities at work. One survey of US adults in February 2022 found that 52 per cent of Black workers believed that working from home is better than working in the office when it comes to advancing in their careers and 63 per cent of Black workers said that they feel more ambitious when working from home versus the office.36 Although interviews of BME workers in the US in 2020 37 found fears of isolation and reduced advancement when working from home.

Surveillance and monitoring

The pandemic and the rise in homeworking has also led to an increase in the use of surveillance systems by employers. According to Migliano & O’Donnell 38 the global demand for employee monitoring software increased by 80 per cent in March 2020 compared with the 2019 monthly average, with many becoming more invasive in terms of what data is being gathered of the worker. Previous TUC research shows that BME workers are more likely to be monitored at work in comparison to White workers, with one in three (33 per cent) Black workers reporting all their activities in the workplace were monitored, compared to less than one in five (19 per cent) White employees.39 Although this is across all workers, not just those working from home. The same poll found that a third of all respondents who only work from home thought their employer monitored their devices such as emails, browser history and typing. No further breakdown across ethnicity was given in the data.

Impact on wellbeing and work-life balance

Looking at the impacts of home working on wellbeing and work-life balance. There is a wealth of literature that discusses the positive well-being outcomes of flexible working for workers, including job satisfaction, and work-life balance, 40 yet studies that examine the difference between different ethnic groups are rare.

Preferences for the future

One clear pattern that is observed in the existing literature is that BME workers have a high preference for working from home. Previous TUC research found that 89 percent of BME workers in the UK who were working from home during the pandemic would like to continue to work from home in some form in the future.41 This is similar to findings when asked of other groups of workers. 42 A poll of 5,444 UK employees conducted by the Business in the Community in November 2021 43 found that one in three (32 per cent) ethnic minority workers have left or considered leaving a job due to lack of flexibility, compared with just 21 per cent of White workers. The same survey notes that 50 per cent of BME workers have noted that caring responsibilities have prevented them from applying for a job or promotion, compared to 40 per cent of White workers, implying that BME workers may higher unmet care needs and therefore the need for flexible working.

As we can see from the literature of experiences of hybrid working, there is very little on the experiences of BME workers in the UK compared to the US. From the UK, we do know that there is a strong preference for some form of home working but that there are potentially greater fears around the impact flexible working can have on careers and the potential for increased monitoring and surveillance of BME workers. The literature review informed the design of the diary study.

Findings

In this chapter, we summarise some of the key findings of our digital diary data focusing on key themes that emerged including the benefits of hybrid working, flexibility stigma and impacts on monitoring, overwork and presenteeism, experiences of racism and home working, exclusion and isolation when working from home and good practice.

Benefits of hybrid working

There was a strong sense from participants that home and hybrid working had brought clear benefits to both their personal lives and work. These can be grouped into productivity, work-life balance, and accessibility of work.

Productivity

Productivity was one of the largest themes in the research overall, with the theme of productivity tagged 48 times and participants generally associated hybrid working with improved productivity due to the reasons cited below.

Reason 1: Better able to focus

One of the most common reasons participants cited for improved productivity was being able to carry out focused work at home and not be distracted by noise and interruptions as they are when in the workplace. This is supported by wider research on home working, which finds that people experience fewer distractions when at home.44

I find that I'm able to focus so much better because I'm not being distracted by all of the office sounds and everything else that's going around me.

However, this wasn’t a universal experience and one participant talked about being distracted at home by her partner which resulted in working late into to evening and preferred being in the office where there were less distractions.

Reason 2: Working at more productive times

Some also said that working at home gave them the flexibility to work at times where they were more productive, for example one participant said they could start work at 7am as they were “an early starter”. One participant’s experience also demonstrated how working from home and use of online meetings could improve an organisation’s ability to provide its service. Hosting remote meetings meant this participant was able to meet clients when they finished work whereas previously face to face meetings always had to be held in office hours. Not having to commute or be at a set location meant workers could flex their hours to be more productive.

Reason 3: Making best use of home and office

Many participants said that working in a hybrid manner allowed them to take advantage of what is best done at home and best done in the office and were able to structure their tasks around their location to work more effectively.

A way to productively work in both settings, so in person I find it great to be able to connect with staff and to have in person meetings. But at home, I really value being able to work independently, and especially when I'm writing… it's definitely a better setting than being in the office.

Reason 4: Greater collaboration with people in different geographic locations

Participants mentioned that home working and gains in technology had made it far easier to communicate with and get to know people in other sites. People spoke positively of the time this saved but also the increased number of relationships they were able to build which improved their work. This is important when thinking about how employers ensure collaborative working which can be achieved both online and in person.

We're based in different locations... we would perhaps, you know, catch up on the phone once a week or face to face once a month, but working from home on the Teams, it's a lot easier to communicate and meet with each other and share ideas of what we need to do and what is expected.

Work-life balance

The majority of participants felt that hybrid working had a good impact on their work-life balance. This was largely because participants used breaks and what would have been commuting time to spend time doing things they enjoyed. In addition, not being tied to strict 9-5 workplace hours meant people were able to flex their hours, for example start earlier in the morning or finish later in the day, to better balance work and life whilst still doing their working hours overall. Improved relationships with family and loved ones came out as one of the biggest themes.

It has allowed me to be present in the house, be visible to my kids, be able to do pickups and drop offs, attend my child's assembly. I can quite flexibly do that and pick up whatever I've missed later on in the evening or earlier the next day. It's made a huge difference to my life, to my wellbeing. Woman, living with children.

Working from home has really improved my relationships with family as it's so much easier for me to visit them after work, or even pop by for lunch. Most of my family live less than a half hour's drive away (I live alone), but leaving the office at my usual time generally means that by the time I'm home it's too late for me to pop by (particularly my relatives who are not in good health).

As well as being able to attend key milestones in children’s lives and see their children more, one participant specifically talked about how flexible working had supported their ability to manage childcare and the costs associated with this. Her remote working allowed her to work close to childcare when previously she had to get taxis between childcare and work at the end of her shift saving her about £40 each time.

Another theme was increased time spent resting, doing things they enjoy, or being able to manage domestic labour, such as chores, doctors’ appointments etc. alongside working as opposed using weekends or annual leave to carry them out.

It used to be the case that if I needed to… arrange an [GP] appointment… I would have to ask for like maybe some time off. Whereas they're all local to me here, I can just do it. Come back half an hour later and continue working and there's minimal disruption.

The vacuum cleaner is because being able to spend breaks / lunch time keeping on top of chores doing small errands means that it’s easier to manage home life. This means that weekends aren’t spent catching up from having a lack of time in the week.

Participants also noted the positive impact that home working had on their physical health including stress reduction and more time to exercise.

I've picked this photo of my garden as I spend the time I would've spent commuting outdoors enjoying nature and looking after my plants. I find that getting out in the garden is brilliant for reducing my stress levels - as is not having to deal with a hectic commute every day!

If I wasn't able to WFH I would spend 4 hours travelling a day minimum. WFH has allowed me to start looking after my health and train for and complete a 5k charity run.

The benefit of not having to commute everyday was mentioned frequently by participants including the time they gained back and having more energy for work and home life. However, there were mixed feelings amongst participants as to whether working from home saved them money. Some did say that not commuting saved money, but others mentioned increased costs associated with food, energy bills, internet, and equipment to work from home.

Accessibility and inclusion

Participants also talked about how home working had made working more accessible. Home working has the potential to ease the burden on carers, in particular women who shoulder the majority of care. This chimes with previous research which has shown that increased flexibility would help to reduce gender pay gaps. 45

Another theme that came out strongly was the accessibility of home working for disabled participants. Nine of the final 20 who took part in the study identified as disabled. This included making it easier to attend medical appointments alongside work, being better able to manage anxiety and sensory impairments, and how technology has improved accessibility for some.

As an introverted extrovert with some anxiety having calmer days at home helps me manage sensory input a bit. Disabled participant.

Think for me in terms of accessibility... working from home has actually made the materials are more accessible for me, so that's linked into actually having equipment and the IT and the technology to support me. Disabled participant.

This tallies with multiple studies that have shown that home working can be an important reasonable adjustment for disabled workers.46 Although, it is important to note that home working will not be beneficial for all disabled workers, as demonstrated by one of our participants.

I actually have a few mental health problems, so I feel like working from home hasn't helped me at all, because I'm always on my own. So, I've struggled a lot. Disabled participant.

Due to the range of impairments, people’s preferences and working styles, workplace-based working may be more suited to some. Employers should therefore not assume ways of working for disabled workers, especially as if imposed, home working can present significant risks to disabled people.47

The popularity of hybrid working was also shown in preferences for the future. 17 of the 18 participants who responded stated they wanted to remain working in a hybrid pattern and one participant said they would like to return to a workplace full time. 14 participants also said they would be reluctant to take a job in the future that didn’t offer flexible working and/or that flexibility would be essential when job searching.

The reluctance to move jobs without flexible working arrangements demonstrates its importance in recruitment and retention for employers. Participants also noted that flexibility should be something discussed in the recruitment stage and should be available to everyone from day one in the job, rather than something that is earnt over time. Other participants stated they would like more security around their hybrid working, for example for it to be in their contract rather than a workplace policy. The quote indicates that this links to the continued stigma that we see around flexible working.

There's always that kind of underlying kind of thought and it's kind of looming over you that you know at some point you could be called to come back into the office five days a week. Even though my role is not a customer facing role and it is, it has been said before that working from home is a privilege and not a right.

Conclusion

As seen in this section, hybrid working is now an expected part of work in certain sectors and has clear upsides for workers, which they may be unwilling to give up and is key promoting equality at work, which is supported by other research. The section on productivity also demonstrates the benefits that home working can have for employers, as well as a more diverse recruitment pool 48 , maintaining staff morale and improved retention. Employers should therefore see hybrid working as part of their work to improve workplace wellbeing, productivity and equality. Viewing hybrid working as beneficial for all means negative views of it are likely to be reduced and workers will be better able to access flexible working arrangements without fear of negative outcomes. It is important to remember however that home working is not suited to all and should therefore be voluntary and not imposed. The next section of the report explores the stigma that still exists about hybrid working and how it intersects with racial discrimination at work.

Flexibility stigma and impacts on monitoring, overwork and presenteeism

Flexibility stigma

Flexibility stigma is the negative views managers and co-workers have towards workers who work flexibly.49 Research shows that home workers are considered not as committed or motivated compared to workers who come into the employer’s premises and are therefore perceived as not as productive, despite evidence showing links between home working and productivity.50 This is closely linked to the ideas that managers tend to perceive workers who are in close proximity to them more positively 51 , and can result in homeworkers being excluded from development training, mentoring and other opportunities. This is why homeworkers in some instances have been shown to experience negative career outcomes compared to those in a workplace.52

Flexibility stigma was one of the most common themes mentioned and the majority of participants acknowledged that there is a stigmatised view against homeworkers as lazy, not productive, not as committed to work and unprofessional compared to those who come into the workplace. This was despite the fact that the majority of participants felt that homeworking had boosted their productivity. The quotes below are examples of what participants had heard from colleagues in the past/previous week;

It's just like, oh, it (homeworking) must be nice… you can just relax and enjoy the weather and stuff … it's that assumption that, you know, it's really relaxing if you work at home. And it's just like we have pressure just as much as everybody else.

it was absolutely seen as lazy to prefer to work from home. … the managing director specifically said she wanted to see bodies in the office to prove that people were working.

Participants experiences implied that working from home was purely for the benefit of the ‘work shy’ individual. They also identified that that the stigmatised views against homeworkers intersected with different characteristics, most commonly their race and age. They felt that discriminatory views, in particular views around BME and young people not working hard enough, contributed to and exacerbated negative views of their home working. The first quote shows how home working can contribute to experiences of racism in the workplace. This mirrors other research which shows that BME workers often have to work twice as hard to be noticed at work and are less likely to be offered promotion opportunities 53 and common opinion that young people don’t work as hard. 54

I can recall an occasion when someone at work (my line manager) in Teams chat had said ‘is XXX still in bed?’. It was 9:45 and I was making my way into the office and a number of trains were cancelled that morning. I didn’t bother to comment back on the remark however I soon learnt that many of true words are spoken in jest as microaggressions.

Work from home tend to be the ‘prissy younger generation’ who don’t know a day of hard work and think logging into a laptop from home is an actual job.

Consequences of stigma

The next section looks at common themes came through that were connected to, and in part due to, the stigma of home working.

Monitoring and micromanagement

Previous TUC research shows that BME workers are more likely to be monitored at work in comparison to White workers. One in three (33 per cent) Black workers reported all their activities in the workplace were monitored, compared to 19 per cent of White employees.55 The same poll found that a third of all respondents who only work from home thought their employer monitored their devices such as emails, browser history and typing.

One prominent theme in our study was excessive monitoring or micromanagement that some of the participants had experienced in their current or previous roles. Whilst this behaviour can be found in multiple different workplaces and jobs, for some, it felt like it was a direct consequence of working from home. The quotes show how these practices led people to feel distrust, spied on and undervalued.

In branch we used to have a rota but it wasn’t extreme like this one as if you were not back from lunch at the exact time it wouldn’t show up on any MI. It’s more so now as we are working from home that they monitor our every movement.

[An app} is stored in our mobile from work, every morning you have to bleep in and then you bleep out at the end of the day….When you have a break you choose the option and want to break...you press end of the break. If you going to the office, you will bleep into the office by scanning a QR code as you enter the building.....[it] was introduced this year [2023] and most of the response was negative, it takes a while to get used to it, people feel spied on and we tend to forget to log in and out.

I would say every hour [that my manager checks in]. Beside my manager there are team[s] who monitors [if] staff are logging in every time. My manager check on me through [a programme] where I login and logout. [It] reports or shows whatever I am doing.... If I am on break or lunch I must show on [it].

When you go on break and for any reason you stay longer than a minute after your break time, you get an e-mail saying why did you overstay on your break by one minute.... I would use the word petty because in the course of our work there are times when we stay longer than our shifts.

The above quotes show examples of where software is used to monitor people, but other participants also shared things like frequent messaging, increased number of meetings and phone calls, for example:

And I think that was probably why some of the project managers I worked with in that previous [job] did take it a bit too far with messaging every day for updates. Because in the office, they'll be able to just get up from their desk, walk over, be nosy and look at my screen, and then sit down and feel satisfied that I'm still working.

Like this quote, participants also shared their experiences of being watched in the workplace, for example comments from other colleagues on how often they go to the toilet/take breaks, looking over people’s shoulders at their work and a general feeling of “people breathing down my neck”. They noted that home working provided a welcome relief from this, but it seems that in the absence of this more informal monitoring, some employers have introduced new and potentially more intrusive ways of monitoring such as apps, software and excessive messaging. This has also happened alongside a rise in new technology to monitor workforces overall.56 Participants identified that the excessive nature of it in part stemmed from managers feeling a loss of control and distrust when workers can’t be seen.

Participants also shared that they felt BME workers are monitored or micro-managed more than White colleagues and provided examples of behaviours where they felt this would not have happened if the colleague had been White.

I had to call off sick from work due to anxiety and work stress especially with the non-challenge attitude of my manager and non-empathy shown. He expressed that he'll be checking in regularly to see when I'll be fit to return to work. I felt this was not the approach he would use if I were to be a white employee.

And I think the other danger in there is some managers you know deliberately or easily invoke some of those tools and selectively and negatively against some and obviously who do you guess would be the most affected by that because... in my experience, my observation and other people's experience in conversations, [it’s] people like me, BME [people].

One participant also stated that whilst they hadn’t experienced it themselves, they felt that organisations needed to introduce mechanisms to safeguard against micromanagement and bullying of BME staff given that home working can exacerbate this behaviour. This quote is in the context of home working, but micromanagement and bullying of BME staff can be experienced in all environments and therefore employers must take steps in all areas of the work.

We discourage this attitude to micromanagement and really, really picking on people because to me that's an element of microaggression. It's an element of bullying. [but] here is still a problem around microaggression micromanagement. Using Microsoft Teams to check when somebody's at their desk, when somebody's perceived to be working and that is something that needs to improve….. companies need to have safeguarding mechanisms and make sure that hybrid working doesn't extend into bullying and exclusion.

Greater monitoring is also concern because previous research by the TUC 57 shows that BME women are more likely to be unfairly disciplined. Increasing in monitoring is not only an invasion of privacy and creates distrust but could also lead to cases of unfair disciplinary action or greater consequences for BME workers.

Flexibility paradox, presenteeism and the need to prove your worth

Despite views that home workers are not as hard working, several studies have shown that when workers work from home, they tend to work harder and longer with work encroaching on their personal lives.58 This “Flexibility Paradox” 59 was observed in the study. We found that close to two thirds of participants documented some experiences of overwork and long-hours work whilst working from home.

Home workers tend to work harder and longer hours for different reasons.60 Previous research shows that this includes employers using the blurred boundaries between work and private life to add additional workloads, and that the provision of flexible working is seen as a ’gift’ from employers which puts an obligation on employees to work harder in return.61 This can especially happen when flexible working is not normalised across an organisation. Thirdly, it can be due to flexibility stigma. As it is assumed that flexible workers are not as committed and productive, workers work harder and longer to compensate for such biased views. Finally, it can also be caused by workers wanting to succeed and do well at work, but this is also driven by the competition that workers feel to stand out in an insecure, individualised labour market where workers have weak bargaining power.62 Therefore, working long hours is used to compete and protect career and job security.

Long hours

We saw evidence of work intensification in the study for example starting work early and not logging off in the evening. Others spoke of not taking as many breaks at home, compared to when working in the employer’s premises where there were natural breaks due to speaking to colleagues, getting coffee, socialising with colleagues etc.

We work too many hours especially when working from home as you tend to forget to take a break. Also not having to travel to work I tend to log in as early as 8 and sometimes don’t log out until 6pm.

Rather than taking the lunch breaks that I am allowed to take I often find myself working through lunch and eating at my desk….Whereas in the office it seems you are able to take lots more breaks - go out for lunch and even coffee in one day.

From some of the quotes, it also seemed that participants viewed homeworking as a tool to manage increasing workloads. This shows that without policies in place, there is risk for employers to exploit the ability to work longer days by pilling on more work.

Last night I was on my computer until 12:00 o'clock at night. This morning I woke up at 8:00 o'clock to start again, the heat and the claustrophobia. Just I'm just become frustrated today. It's I've got so much work to do and I just can't keep on top of it.

There was evidence that working long hours was possible because of access to work equipment. This was regularly compared to when working in the office where respondents noted that it was or would have been difficult to keep working late into the evening/night.

At home so you can’t really cut off from work. Sometimes you are tempted to log on after hours or on a weekend to catch up on emails and messages whereas if we were in the office we wouldn’t be able to do that.

This picture is of my laptop on my sofa when I have been working late. It depicts a struggle I have with finding a cut off point between work and home and the imbalance I experience in this particularly when working from home. It(homeworking) makes it difficult to set and keep after work plans with friends and family because I get carried away with work. I think this is largely because the laptop is just there it feels like the work day doesn’t really end as it would if you were to leave a computer and desk in an office. Especially if you hear an email or message come through.

Participants also shared that working long hours felt like an expectation as they were working from home and something they did to prove themselves for career progression to the detriment of their wellbeing. This expectation to work longer hours and be more available was presented in contrast to a general acceptance of people engaging in other activities when in a workplace for example socialising and coffee breaks. Previous studies demonstrate that there is a belief that such behaviours when done in the office is assumed to be included as working hours.63

When the body has absolutely had enough, laptop goes to the side, usually in sleep mode rather than off because I would have been in the middle of something. And often then, I would just sleep in the sofa. This is not required of me, and I am trying to get out of it now, but it started as a necessary regular thing where I had to make the impossible possible…… Previously too, it would be for additional responsibilities I took at work that required work time, but I did not ask for time for, doing work training at home, and taking additional learning for a possibility of career progression that still hasn't happened anyway etc. Then the amount of work you fit in becomes a pattern, and setting no boundaries becomes the norm.” “When working solely in person, you can't stretch your hours of work beyond what it is, and you can't be tasked for your non-work hours when you're not there (in the office). But working from home allows that.

I feel that there is a slight expectation of people working from home to work longer hours because we’re so near our desk - often I miss my lunch, take spontaneous calls at awkward times or respond to emails late at night because of this. I think in the office there’s that physical boundary of leaving your desk to eat lunch or go home which means people don’t request you as much as when you’re at home.

Digital presenteeism

Another pattern we observed in many entries was around the workers feeling the need to perform digital presenteeism – the need to be always on and always available for work. Participants felt a need to provide constant evidence of working and there seemed to be a hyper awareness of online presence. This was most commonly mentioned through examples of taking your phone on breaks and using Teams status to show your availability, which seemed to equate to be seen at your desk. The second quote also shows how colleagues were using such systems to monitor homeworkers, with an assumption that if not ‘available’ via Teams that workers were not working again demonstrating flexibility stigma.

My final picture is one of me during my walk on a ‘break’ from work… having taken my work phone! I find that I struggle with feelings of guilt if I ever leave my desk from working at home. This isn’t something I do if I’m in the office - I don’t take my work phone with me and I’m non-contactable. I think this worry and perception stems from the idea that people who work from home ‘aren’t actually doing any work’ and so to prove the point I take my work with me, to the detriment of having actual time to switch off and give my mind a break - when I am perfectly entitled to…..This may or may not be directly caused by the projections of others or merely a result of a few years of negative experiences and circumstances where I have been made to feel this way by colleagues - almost institutionalised and internalised perceptions that are now affecting my home working habits.

Sometimes I have to work from a separate laptop so it shows me as ‘away’ on Teams, when I am just working elsewhere. A message was posted by a colleague into one of the work chat Teams chat asking if I was watching TV or had switched off for the day as a joke.

Digital presenteeism also took form where workers updated managers and colleagues regularly about exactly what work tasks they were doing, which as seen in the quote below was directly related to the stigma around working from home.

I do make sure that when I'm in the office and if I am leaving early to come home and make my colleagues aware that I will be working when I get home so as to avoid any assumptions that I'm going to go home and put my feet up and not be working. As you know there have been slight comments before about going home and you know only working half a day (in the office).

Intersection of stigma and racial discrimination

The quotes above demonstrate how home/hybrid workers work longer hours and enact presenteeism due to the availability of technology but also as a way to compensate for any potential bias against home workers’ and their work capacity and to overcome any potential feelings of insecurity about their role and job.

Our study also found that the pattern of overwork and digital presenteeism cannot be detached from workplace racism. Participants talked about how they need to justify what they are spending time on or ‘prove themselves’ was heightened for BME staff to ease any negative views against work commitment and productivity. The quote below demonstrates how this had become part of the normal working experience for some participants.

I do (think that BME workers have to communicate more to their managers/colleagues than white workers). I kind of forgot I do that because it's so automatic now. In my career so far I've been the only mixed race/black woman on the team, so I'm used to constantly communicating what I'm working on, how it's going, etc, so that people know I'm capable.

The following two quotes also demonstrate how participants felt that overwork and long hours was driven by feels of insecurity in comparison to White workers and that taking on additional work and working longer hours was a tool to try and gain career progression and recognition.

I feel like we have to justify it more than our white colleagues....in terms of I think how secure we feel in our roles plays a big part in it and I think going forwards. You know we have to we, as with anything, I think we have to prove our worth a little bit more than say our my white colleagues in terms of our productivity and how we do.

I didn’t sign out till about 2:00 AM, which is very common with me and just from experiences of being and feeling vulnerable. And this is not from speculation, just from how the work system has responded to that, to myself directly or to someone I know. You have you kind of feel the need to do, or have had the need to do much, much, much more in order to be safe and feel fairly treated….So I have developed about the negative habit of having to work to the overall workload which never would clear, but then feeling a need to clear it, … Rather than working according to my work hours that I’m paid for, that I’m expected to do.

After sharing this, the same participant acknowledged that the long hours were a way to make up for the perceived failures of herself and people like her, who when asked she said were BME workers (see quote below). She acknowledges that she works longer hours to counteract any discrimination that might be happening. She had also shared an experience of being unfairly dismissed at her previous workplace and with patterns of bullying and aggression at work where her work contributions and commitment were questioned, showing how the trauma of racist experiences at work carry on to new roles and impact behaviour.

It (long hours) was the way of making up for failures, other’s failures, that I felt the need to compensate for, lest it is made my failure. And that was exactly what was attempted in the end, except I was safeguarded against it…. I and others like me have previously been made to perform more tasks than were required, like being asked to do things more number of times than is required.

Conclusion

In this section, participants’ quotes demonstrate how flexibility stigma and the views that home workers as not as committed still exist and intersect with racial discrimination that BME homeworkers experiences. This applied to not only the stigma itself, but the negative practices used by employers as a consequence. Participants felt that BME workers were more likely to be monitored or micromanaged working from home, which is supported by wider research on monitoring of BME workers and gave examples of new monitoring technology implemented as a result of home working.

Whilst overwork exists in many roles, our participants’ experiences showed that home working has potentially allowed for a pattern of overwork. Feeling the need to ‘prove yourself’ through presenteeism and long hours when working from home are intensified for Black workers who face the double burden of flexibility stigma and racism around their work ethic. In addition, home working and the availability of technology has provided a mechanism to work longer hours when BME workers feel they need to prove their value to overcome negative views of home workers and discriminatory views. Home working should not result in work intensification. Actively removing stigma and other negative connotations connected to home working by normalising flexible working and providing workers with better protection against overwork, discrimination, and excessive surveillance/monitoring will help reduce this.

Experiences of racism and home working

This section looks at the experiences of racism that participants shared usually in relation to racist comments. Often workplace racism is wrongly reduced to either a series of random one-off events and/ or the implicit attitudes and unconscious biases of an individual. However, workplace racism, including racist comments or microaggressions, are the manifestations of structural and institutional racism and in addition work to reproduce racial inequality in the labour market.64

Home providing safe spaces from racism

Throughout the duration of our digital diary study, participants shared stories of racism above and beyond those that intersect with bias against home and hybrid workers. Whilst some participants shared past experiences, entries also related to things that had happened in the past few days. Experiences included racist remarks from colleagues about appearance, the pronunciation of their names, questioning individual’s seniority and other comments that marginalise BME workers, forcing dominant working cultures as the professional standard in the office.65

A white colleague made a passing comment/‘joke’ that they would be sitting at the other end of the office away from the ‘loud ones’.. the people being referred to were all of colour.

The white instructor said ‘I don’t know where to begin on how to pronounce your name, can I call you Laqeesha’ as a ‘joke’ to a black colleague on the call.

Called ‘my Indonesian friend’ by a colleague.

When I go into the office and introduced to new colleagues, I find that they assume I’m a lot more junior than I am – for instance when I met someone last week and said I worked in the team I’m in they said ‘you’re an admin officer right?’... I think this is tied into my identity as a black woman.

This led to many of our respondents to change their behaviour to avoid racism or to have their performance evaluated fairly by their managers.

This perception came about a few years ago when my manager... He mentioned about how cultural impacts might have impacted my performance- he was referring to his perception of me being deferential. Since then, I noticed the need to behave more like White people (i.e. being confident, working to get noticed etc) to succeed at work, more so in my current work.

I cannot bring my whole self to work or that I have to put some sort of front up so that I can act and perform in the way that makes my white colleges most comfortable…. It has made me feel like a fraud or that I’m not being true to who I am, and it’s making me question myself introspectively.

Given the comments above it is not surprising that some participants noted the safety and comfort that home working provided them, allowing them to avoid these experiences of racism or step away from the incident when it happens.

So I would say it [working from home] actually helps to create that balance cause if you kind of feel like the atmosphere in work is toxic, you still find your space when you come back home to work from home.

…the racism, if I do face it, is short bursts of it on Zoom meets, MST meetings and that kind of thing, and I can just park it and I get on with my work. So in some ways it’s actually quite beneficial. So, if I experience racism, it’s there it’s not in front of me. I don’t have to face it every day, if that makes sense, if I’m not going into the office… so I just get on with things.

I am able to step away from micro aggressions and racist behaviour compared to being in the office. From past experience where I felt there has been racism it’s been very difficult to challenge it knowing that I would need to face those members of staff daily.

It would be ignorant to think that home workers do not experience racism as they are impacted by institutionally racist policies and practices as well as comments. Workplace racism cannot be solved by increased home working and increased working from home must not replace the urgent need to address racism in the workplace and the reasons for workers feeling marginalised or unfairly targeted at work. However, as there are wider conversations ongoing about the balance of home working vs the workplace, an important but often missing part of this discussion is whether BME workers feel safe in working environments, both in workplaces and when working from home, and what kind of in person workplace we are asking BME workers to return to. Our participants indicated that home working could provide respite from the mental and physical toll racist comments can have demonstrating the essential need to tackle this and the root causes of it. In addition, an often-quoted reason for being in workplaces is for socialising, collaboration, or culture building but the benefits of this may be limited for people who don’t feel part of the culture to begin with.

Women taking part in the study also referenced how working from home made their lives easier in relation to appearance. Research by Fawcett found that BME women were more likely to change aspects of themselves at work in comparison to out of work. 39 per cent of Black women of African heritage surveyed said that had changed their hairstyle ‘a great deal’ or ‘quite a bit’ at work, compared to 17 per cent of White women.66

Three of the women taking part in our study specifically reference appearance and that working from home meant they thought less about it. Their quotes demonstrate how the constant negotiating of dominant cultures takes time, mental effort and creates discomfort.

I’m not dressing up for work... there’s extra preparation when I’m going into work. Woman participant.

I get to spend more time with the kids by saving on the commute time and time spent dressing up for work. Woman participant.

Working from home helps me bring my full self to work because I feel more comfortable and familiar in this safe environment. I feel more able to dress how I would like, wear my hair how I would like and act in an unrestricted/masked way. Woman participant.

The experiences of racism that BME women shared were often in relation to appearance, including the quote below and one participant sharing how BME workers are continually told their natural hair does not look professional.

One situation (in a previous job) was coming into the office with my hair in box braids....one coworker kept asking if my braids were painful, did they hurt. Later that day when I had a headache from being in non-stop meetings, I was asked again if I was having a headache because of the braids 😂 Moments like that highlight the very real possibility that I’m the first mixed/black woman they’ve worked with closely, and that makes me uncomfortable. Woman participant.

Racism in online spaces

Racism also takes place when working from home and in online spaces, and our participants shared examples of this. A frequent theme that came up was feeling like their voices were not heard in online spaces, which is similar to reports of racism in physical workplaces. There were examples of our participants being spoken over and their authority and expertise being questioned more often in comparison to White staff.

I often pass for white in person, so unless somebody knows my name, they might assume I’m white...Over email and IM, where people only see my name but not my face (as a white-passing person), I experience more microaggressions around my name, repeatedly misspelling or muddling first name and surname.

I noticed something this week again where I am left off emails and in meetings only my colleague who is white is referred to.

I was on a couple of calls where some participants did not know me where I felt ignored and constantly spoken over – with all questions directed to two non-BAME member of my team who were also in attendance. Even when my team members (both 3 grades my junior) came to me for validation of their answers, further questions were directed to them.

However, a specific theme that also came through was how online meetings could contribute to inclusionary communication and some participants felt online meetings had made it easier for them to voice opinions and feel heard in the workplace. Chat and hand raise functions in particular were mentioned as mechanisms people used to circumvent social dynamics that left them feeling unable to. At the core of this is building inclusionary practices into day-to-day communication and interactions whether these be online or in person.

I’m fairly junior, am told I’m soft-spoken, and recognise that my gender likely feeds into this too, but I do feel that White colleagues of the same age and gender aren’t talked over as often as I am. …...Much easier to participate in online meetings, things are much more equal in terms of getting a turn to speak (putting a virtual hand up is very easy, but putting actual hands up in an in-person meeting isn’t done), and I don’t have the burden of e.g making sure I sit opposite the meeting chair so I have a chance of catching their eye so they can help create space when I would like to speak. I really make use of the chat function too to add points here and there. I feel a lot less self-conscious when attending a virtual meeting and am thus able to concentrate better and participate more than when in-person. Woman, 25-34.

I find it easier to raise a point as I can always put it in the comments section if there isn’t time so others are aware or raise a hand so there is some order in who speaks next. Woman, 35-44.

The hands up function that for me has been really beneficial in terms of making sure that I am able to contribute in meetings and that my voice is heard. Usually sometimes in person, I feel like I have to be a bit quieter or I can’t speak out because of various different negative stereotypes but the ability to sort of be able to have my voice heard in that kind of way has been really beneficial. I think in a room full of white colleagues, I feel like I have to act a certain way, or that my feelings and thoughts and ideas and opinions are never really heard as loud as theirs... So that’s something that’s really helped me in terms of gaining confidence in myself and actually being able to contribute to discussions. Woman, 18-24.

Many of these comments came from BME women, and some from younger women showing how intersections between race, age and gender impact experiences of discrimination at work.

Conclusion

An important but often missing part of the discussion about benefits of being in a workplace is whether BME workers feel safe in working environments, both in workplaces and when working from home. Our participants indicated that home working could provide respite from the mental and physical toll racist comments can have, in particular for BME women around appearance, demonstrating the essential need to tackle this and the root causes of it. However, examples of how racism pervades all working spaces, including home, were also shared.

Exclusion and sense of belonging when working from home

As part of the study, participants talked about their sense of belonging to an organisation as hybrid worker and linked to this, experiences of exclusion or inclusion with co-workers and managers.

Line management practice

One of the prominent themes that came through was participants relationships with their line managers and many shared exclusionary experiences. Participants shared cases of meetings being arrange without those working from home, line managers not scheduling one to ones, not having access to information that those in the workplace had, being excluded from work allocation and managers not being as available to people working at home compared to those they saw in person. A common theme that came up was that managers were too busy to provide the line management support people needed.

We’re supposed to have regular one to one conversations and that hasn’t actually happened... Conversation we had earlier this week was the first one in maybe 3 months.... Also, I work from home a fair bit, she also goes into the office a lot more than I do. So, I think compared to colleagues that go into the office, she probably has a lot of face to face interaction. So, I probably miss out on that.

To be honest, I never felt checked in on and actually I would have liked him to check in on me more. That’s both when working from home and in the office...... I think part of that reason is because I work in a really busy environment where he would be in back-to-back meetings basically all day.

You’re capable of doing so much more but you’re not given an opportunity to do that. And yeah, working from home is harder to show to my manager because there’s only so many emails and messages you can send to say if you want to do this, you want to do that, or I can help with this task, I can help with that task. But then your manager's too busy for you, so you don’t really get anywhere.