Companies for People - How to make business work for workers

In our current economic model, the private sector is at the heart of our economy and plays a key role in economic growth – but the benefits of economic growth are not shared fairly among its participants. The quality of economic growth, and who benefits from it, are affected by how rewards, rights and power in businesses are distributed. This report sets out why we need reform to ensure that economic growth benefits everyone and our proposals to make it happen.

Unjust rewards – to capital and labour

Dividends and wages

Since the global financial crisis, dividends have grown over three times faster than wages. Between 2008 and 2019, dividends grew by 6.3 per cent per year, while wages grew by 1.9 per cent (both nominal). In real terms, that is after inflation is taken into account, average earnings fell by 0.3 per cent per year, while dividends grew by 4 per cent per year. Average weekly earnings remain lower in real terms than in 2008, while dividends in 2019 were 44 per cent higher.

If pay had kept up with dividends over this period, the average worker would in 2019 be £16,400 better off.

Had dividends simply grown in line with inflation between 2008 and 2019, companies would have saved £440 billion. Had wages kept pace with inflation between 2008 and 2019, working people would have received an additional £510 billion in wages.

In the two decades before the financial crisis, both pay and dividends were growing more strongly, but still unevenly, with dividend growth outstripping wage growth by a ratio of two to one. Between 1987 and 2008 dividends grew by 10.4 per cent per year and pay by 5.2 per cent per year (both nominal). In real terms, dividends grew by 7.4 per cent per year and pay by 2.4 per cent per year.

Dividends, profits and investment

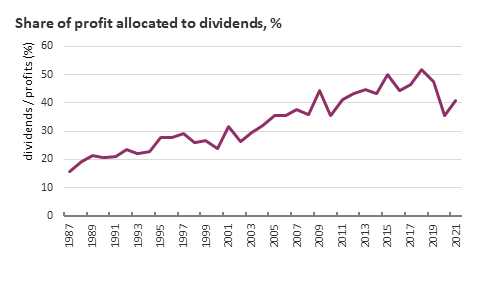

The share of profits allocated to dividends has increased significantly over time, rising from 16 per cent in 1987 to peak at 52 per cent in 2018. It fell during the pandemic but is now rising sharply once more, reaching 41 per cent in 2021.

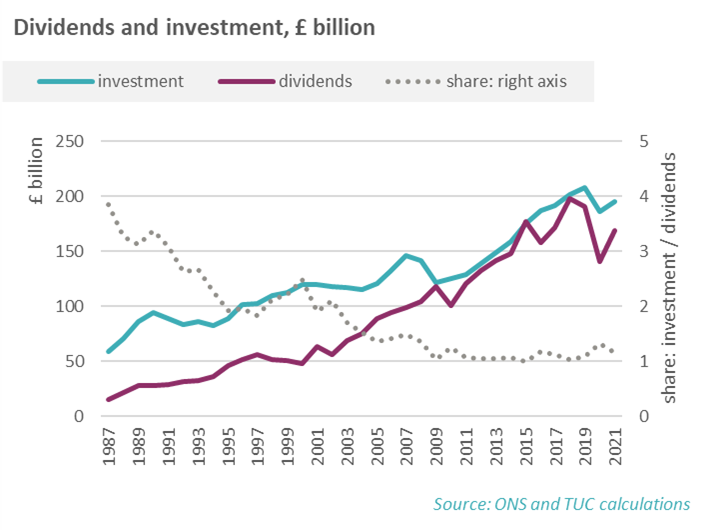

The opportunity cost of spending ever-higher amounts on dividends extends beyond the impact on wages. In 1987, business investment was around four times higher than dividends; now, they are close to parity.

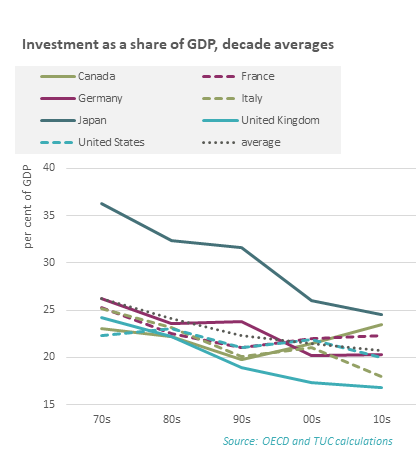

The priority given to shareholder distributions has contributed to the UK’s poor investment performance relative to other similar economies.

Rights, power and business models

The disparity between the growth in dividends and wages reflects the distribution of rights and power in Britain’s businesses.

Shareholder rights and interests

UK company law and corporate governance prioritise the interests of shareholders over those of other stakeholders. Shareholders have significant rights in corporate governance, while other stakeholders, including workers, have no significant corporate governance rights.

This system is flawed even in its own terms. Institutional investors generally hold shares in hundreds of companies and do not have the staff capacity to analyse and engage with all the companies whose shares they hold. This means that investors often do not make use of their extensive corporate governance rights, including on important areas such as auditor appointments. Investor votes on remuneration reports have failed to bring executive pay into line with the expectations of the public.

The average holding period for UK shares has declined from around six years in 1950 to less than six months. The short-term nature of share ownership and the increased reliance on strategies based on share trading undermine the argument that there is a convergence of long-term interests between investors, the company in which they invest and other company stakeholders. For many investors, their interests are no longer tied to the long-term success of the company and hence other stakeholder interests, but instead to short-term movements in its share price.

Holding hundreds of shareholdings allows institutional investors to spread their risk, undermining fundamentally the argument that investors bear the greatest underlying risk in companies. Workers, on the other hand, cannot diversify their risk in relation to company failure and if things go wrong lose their livelihood and security and sometimes their home and health.

A range of other research set out in the report supports the conclusion that directors prioritise shareholder returns to the detriment of long-term company success, workforce interests and wider economic resilience.

Corporate complexity

Many large companies, both listed and private, operate through a complex web of corporate structures and holding companies. This can damage corporate governance standards, transparency and employment relationships.

Private equity and other private ownership

The ownership outright of companies by private equity funds and other private companies exposes the problems of shareholder primacy. Some private equity and other private owners extract significant economic value from their portfolio companies, leaving the latter economically vulnerable and with less money for wages, training and other investment. The requirement that company directors should serve the interests of shareholders makes this destruction of economic value legal.

A company embodies productive capacity, innovation and skills, its workforce, suppliers and customers and the law should not give a corporate owner the right to destroy this as though it were a pencil or some small thing that can be disposed of without consequences to anyone but the owner.

Business models based on fragmented employment relationships and insecure work

There has been a significant increase in the use of business models such as outsourcing, franchising and the use of labour market intermediaries that weaken and disrupt employment relationships. This leads to organisations that reap the economic benefit from work having little or no responsibility for those whose work has contributed to their operations and success, making it much harder for workers to secure their rights at work.

There has also been a significant rise in insecure work. TUC analysis shows that 3.7 million people, around one in nine of the workforce, are in insecure work, including those on zero-hours contracts, casual and seasonal workers and people in low-paid self-employment. Insecure work has a huge impact on people’s lives, damaging physical and mental health, family life and wellbeing.

These employment models may in part be the result of business schools promoting strategies based on shareholder value that lead to workers losing out.

Worker power

It is through trade unions and collective bargaining, rather than corporate governance rights, that workers in the UK have been able to influence the decisions that affect them and bargain for fair pay and conditions at work. However, union density and collective bargaining coverage have declined significantly, falling respectively from 54 per cent and over 70 per cent in 1979 to 23.1 per cent and 26 percent in 2021.

Research shows that collective bargaining promotes higher pay, better training, safer and more flexible workplaces and greater equality.

Recommendations

Change company law to reform shareholder primacy and promote workforce voice in corporate governance

- Amend directors’ duties to require directors to focus on long-term company success and balance workforce and shareholder interests

- Change ‘employee’ to ‘workforce’ in the Companies Act to require companies to report on their whole workforce, not just employees

- Worker directors, elected by the workforce, should comprise one third of the board at companies with over 250 staff.

Restore power to workers by boosting collective bargaining

- Unions should have access to workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership and collective bargaining (following the system in place in New Zealand)

- The process for establishing union recognition and collective bargaining should be simplified

- Fair Pay Agreements agreed by unions and employers should be established to set minimum pay and conditions across sectors.

Address corporate complexity and exploitative business models by giving workers rights to scale up bargaining across business operations

Where workers have union recognition at one workplace within a multi-site organisation or at one bargaining unit in a larger organisation, the union should have the right to:

- contact workers at another site or bargaining unit to promote union membership

- ballot a wider group of workers within the organisation, defined on the basis of geographic, occupational or organisational factors, to offer union recognition and a collective bargaining agreement without reaching the required membership threshold within the additional bargaining unit or workforce group.

Tackle fragmented employment relationships by introducing strict joint and several liability for core employment rights in UK supply chains

A system of strict joint and several liability for core employment law standards should be established so that organisations have a legal responsibility to protect basic workplace rights for workers in their UK supply chains.

Introduction

In our current economic model, the private sector is at the heart of our economy. Businesses large and small fuel economic growth, provide jobs for our communities, produce products and services that people want or need, buy products and services from other businesses and help generate taxation to fund our crucial public services. Yet, public trust in business has declined over recent years. The 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer 1

shows that trust in business in the UK fell this year into net distrust.

While business plays a vital role within our economy, that does not mean that it is playing it well. Over the last decade, pay has stagnated, productivity has flatlined and the jobs created have all too often been insecure. Before the pandemic, median real earnings were still lower than in 2008 before the financial crisis and have now sunk still further in the face of rampant inflation. Insecure work rose after 2008 to reach 3.7 million people or one in nine of the workforce by 2019. It then dipped briefly as workers on precarious contracts disproportionately lost their jobs during the pandemic, but has now made an unwelcome recovery back to pre-pandemic levels 2

.

Yet over the same period, rewards to company shareholders have been strong. As this report sets out, since the global financial crisis, dividends have grown more than three times faster than pay. The rise of dividends during a lost decade for real wages illuminates a stark contrast between the returns to work and the returns to wealth. However, this simply extends and sharpens a trend that has been in place for decades, whereby shareholder returns have grown faster than wages. This is unfair, inefficient and ultimately unsustainable.

The scandal of P&O illegally sacking its workforce and replacing them with low-paid agency workers with immediate effect shocked and outraged the public. This is just the most recent of a long list of corporate scandals – including Sports Direct, BHS, Carillion - in which workers have experienced exploitation or lost their livelihoods because corporate practice has undermined, rather than protected, the interests of the workforce. While of course there are companies that strive to be good employers and take the welfare of their staff seriously, poor employment practices and exploitative business models have nonetheless become increasingly mainstream, damaging the interests of the workers affected and weakening our social fabric.

Many of the laws and regulations that govern the way companies operate have been in place since the industrial revolution. The Joint Stock Companies Act of 1844 established a simple process for registering a company, while the Limited Liability Act of 1855 greatly reduced the risks of investing in companies by limiting the losses of investors to the funds they had invested - in the event of corporate failure, investors would not be responsible for settling any debts or losses the company had accrued. The 1862 Companies Act enshrined the legal principle that company governance is determined by members or shareholders, setting out default articles on calling general meetings and voting procedures. The basic principles of this model are still in place today.

From bridges to railways, we still use and admire some of the products of the early joint-stock companies of the Victorian era. But we should never forget the appalling practices that were part of their creation, from child labour, excessive working hours, poverty pay and brutal treatment of workers. The injustices of this system rightly spurred wide-ranging reform in many areas - and yet, the basic premise at the heart of company law, that treats companies as essentially a vehicle for the protection of capital, remains in place.

It is time to reform the way that the private sector operates, with company rewards and returns shared more fairly among all company stakeholders, a voice for the workforce in corporate decision-making and decent work hard-wired into business models. This will require changes in how companies are regulated to remove the prioritisation of shareholder interests, the creation of elected worker directors and wider reform to boost the bargaining power of workers so they can keep a fair share of the wealth they create.

What, why and how – rewards; rights and power; and corporate structures and business models

How power and rewards within businesses are shared has a fundamental impact on our economy and society. This report will examine the distribution of corporate rewards (what); the imbalance of rights and power within corporations (why); and the development of corporate complexity and exploitative business models and practices (how). It will then set out proposals for reform to change the way our economy works and the incentives that shape it so that economic growth is based on good quality jobs.

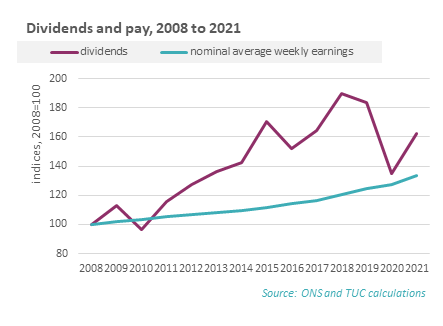

Since the global financial crisis, dividends have grown over three times faster than wages 3

. Between 2008 and 2019, dividends grew by 6.3 per cent per year, while wages grew by 1.9 per cent (both nominal). In real terms, that is after inflation is taken into account, average earnings fell by 0.3 per cent per year, while dividends grew by 4 per cent per year. Average weekly earnings remain lower in real terms than in 2008, while dividends in 2019 were 44 per cent higher.

If pay had kept up with dividends over this period, the average worker would in 2019 be £16,400 better off.

Figure 1 Relative growth of dividends and pay 2008 – 2021

- 1 Edelman Trust Barometer (2022) Global Report available at: https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2022-01/2022%20Ed…

- 2 TUC (2022) Insecure work - Why employment rights need an overhaul available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-why-employment-rights-need-overhaul

- 3 The sources for this section are set out in the data annex.

Had dividends simply grown in line with inflation between 2008 and 2019, companies would have saved £440 billion. Had wages kept pace with inflation between 2008 and 2019, working people would have received an additional £510 billion in wages.

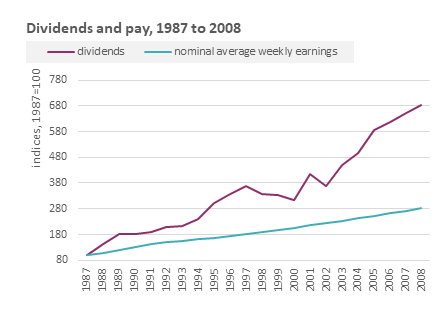

In the two decades before the financial crisis, both pay and dividends were growing more strongly, but still unevenly, with dividend growth outstripping wage growth by a (lower) ratio of two to one. Between 1987 and 2008 dividends grew by 10.4 per cent per year and pay by 5.2 per cent per year (both nominal). In real terms, dividends grew by 7.4 per cent per year and pay by 2.4 per cent per year.

Figure 2 Relative growth of dividends and pay 1987 – 2008

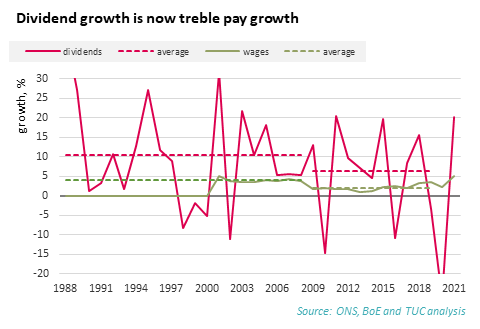

The chart below shows the annual growth rates for dividend and pay across the whole period, with averages for pre- and post-global financial crisis.

Figure 3 Annual growth of dividends and pay 1987 – 2021

The prioritisation of dividends over wages has had grave consequences for working people, stalling attempts to address inequality and contributing to the entrenchment of low-pay and in-work poverty. One in six of the workforce, or 4.8 million people, are paid below the Real Living Wage 4

. A survey 5

carried out in early 2022 found that 38 per cent of people earning less than the Real Living Wage said they had fallen behind with household bills in the past year; 32 per cent said they had skipped meals regularly for financial reasons; 23 per cent said they had fallen behind with their rent or mortgage payments; and 17 per cent said they had taken out a pay-day loan to cover essentials. As well as rendering unaffordable their basic needs, low pay significantly weakens workers’ ability to deal with shocks such as the pandemic or the current cost of living crisis.

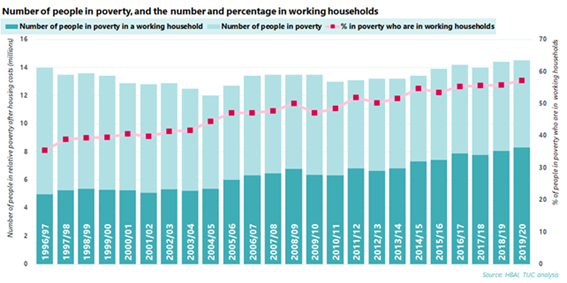

Too many people are finding that work is trapping them within poverty, rather than providing a route out. Before the pandemic, in 2019, the number of people living in poverty reached 14.5 million people, a record high. Even more shocking is that over half of them – 57 per cent or 8.3 million people – were in working households. And too many children are having their future blighted by low pay and poor quality work; three quarters of children living in poverty – that is 4.3 million children - are from working households.

Figure 4 Timeline of number of people in poverty, with working household breakdown

- 4 Living Wage Foundation https://www.livingwage.org.uk/publications accessed 7 September 2022

- 5 Joe Richardson (2022) Life on Low Pay 2022 Living Wage Foundation https://www.livingwage.org.uk/life-low-pay-2022

The share of profits 6

allocated to dividends has increased significantly over time, rising from 16 per cent in 1987 to peak at 52 per cent in 2018. It fell during the pandemic but is now rising sharply once more, reaching 41 per cent in 2021.

Figure 5 Proportion of profits allocated to dividends 1987 - 2021

- 6 Gross operating surplus – the internationally consistent national accounts measure of profit after wages have been paid but before fixed capital investment, property incomes, taxes and other social payments

The opportunity cost of spending ever-higher amounts on dividends extends beyond the impact on wages. In 1987, business investment was around four times higher than dividends; now they are close to parity.

Figure 6 Dividends and investment 1987 – 2021

The priority given to shareholder distributions has contributed to the UK’s poor investment performance relative to other similar economies.

Figure 7 Investment as a share of GDP in G7 countries, 1970 – 2020

The next section of this report will examine the reasons behind the priority given by companies to shareholder returns over wages or investment.

A mixture of company law, corporate governance requirements and the market for corporate control have all contributed to the prioritisation of shareholder interests over those of other stakeholders within UK companies. Workers’ power comes not from corporate governance rights but from unionisation and collective bargaining. However, collective bargaining coverage, especially in the private sector, has declined in recent years. At the same time, corporate complexity and business models based on outsourcing and insecure work have created new challenges for working people to secure a fair share of the wealth they create. These trends have contributed to the disparity between the growth in dividends and wages set out above.

Shareholder rights

All companies in the UK, both large and small, are governed by company law. A core part of this is the duties of directors as set down in the Companies Act 2006, which require company directors to promote the success of the company for the benefit of shareholders. While directors are also required to have regard to the interests of employees, supplier and customer relationships, community and environmental impacts and company reputation, these are subject to the overriding objective of promoting the interests of shareholders.

The priority given to shareholder interests in directors’ duties is reflected in other legal requirements that determine how companies operate. These give shareholders significant rights in corporate governance – whereas other company stakeholders, including the workforce, have none. Shareholders can:

- Elect company directors – annually in the FTSE 350

- Attend company AGMS and vote on all items, including shareholder resolutions, the report and accounts, the appointment of auditors, forward-looking remuneration policy reports and remuneration reports (advisory vote)

- Call Emergency General Meetings or EGMs

- File shareholder resolutions.

In addition, although it’s not a legal right, large shareholders will generally be able to arrange meetings and other engagement opportunities with board members, giving them a direct route to influence.

Government policy over the last 25 years has emphasised accountability to shareholders, rather than regulation, as the means of improving corporate practice. Successive governments have put in place additional reporting requirements combined with voting rights for shareholders to address corporate behaviour, rather than regulating directly. A good example of this is executive pay, where reporting requirements have increased significantly over the past two decades and shareholders now have both a binding vote on forward-looking remuneration policy and an advisory vote on remuneration reports setting out payments over the previous year.

These rights are significant; but their scope it not matched by the extent of their use by shareholders. An example of this is the appointment of auditors. From Carillion to Patisserie Valerie, notable instances of impending corporate failure over recent years have gone undetected by their auditors, whose reports failed to sound any warning of the brewing problems. In 2021, fines imposed on the big four audit firms for misconduct and audit failures reached a record £46.5 million – and this doesn’t include the largest audit fine ever of £14.4 million levied on KPMG in July 2022 for misleading regulators in the latter’s routine inspections of historic audits of Carillion and another company[1]. Despite these well-publicised problems and the importance of effective audit for enabling investors to make an accurate assessment of investment risk, examples of shareholders failing to back the company’s proposed auditor appointments are extremely rare. The average oppose vote on auditor appointment resolutions in the FTSE 350 from 2019 to 2021 was 0.8 per cent[2], while across the FTSE 100 last year, all auditor appointments received over 90 per cent support from investors[3]. This is one of many examples that suggest that investors are not making good use of the rights they hold, rendering our current shareholder-oriented system ineffective even in its own terms.

While remuneration reports typically engender the highest ‘no’ votes at company AGMs, it is still very rare for a majority of shareholders to vote against remuneration reports or remuneration policy. The extensive reporting and voting requirements now in place have failed to address rising levels of executive pay and a growing gap between company executives and average earnings, both across the economy as a whole and with or their own workforces. Median FTSE 100 CEO pay rose from £2.27 million in 2009 to peak at £3.97 million in 2013 and 2017. The most recent figures show that median FTSE 100 CEO pay rose by 39 per cent between 2020 and 2021 to reach £3.41 million[4], far outstripping the rise in average earnings of 5 per cent[5]. The ratio between median FTSE 100 CEO is 109 times the median earnings of a UK full-time worker in 2021. This represents a sharp increase from 79:1 in 2020 when many incentive-related executive compensation schemes were affected by the pandemic-related economic shut-downs, but has also widened beyond the gap of 107:1 in 2019.

There are several reasons why the reliance on shareholder voting rights within our corporate governance system is ineffective and misplaced.

Investors as a whole do not have the capacity to make effective use of their voting and engagement rights. The share of the FTSE 350 held by asset managers has doubled since 2000 from 20 per cent in 2000 to over 40 per cent today. Asset managers hold shares in hundreds or even thousands of companies and simply do not have the staff capacity to analyse and engage with all the companies whose shares they hold. They have to prioritise, generally focusing either on higher risk sectors and those companies in which their stake is highest. While this prioritisation is perfectly rational given their limited capacity, it means that many companies will generate little investor engagement or interest. Many other institutional investors, such as financial institutions, insurance companies and pension funds, also hold highly diversified shareholdings and face the same resource constraints.

More broadly, many asset managers and other institutional investors have proved themselves reluctant to vote against company management and most AGMs pass with little or no investor dissent.

There is also a democratic deficit in the way that asset managers and most other institutional investors generate their voting policies and practices, with little involvement from the savers whose funds have been entrusted to their care. There is a disconnect, especially on some issues, between their voting record and the views and values of their beneficiaries. A clear example of this is executive pay, which remains extremely high despite binding shareholder votes on remuneration policy being introduced in 2013. As noted above, median FTSE 100 CEO pay reached a multiple of 109 times median earning in 2021. Polling[6] carried out by Survation for the High Pay Centre found that only 1 per cent of people think that CEOs should be paid over 100 times their lower and middle paid staff. The most popular option, chosen by 29 per cent of survey respondents, was that CEOs should be paid 1-5 times more, while in total 62 per cent of respondents chose one of the three brackets falling between 1 and 20 times. Rather than reflecting the views of their beneficiaries, the approach of asset managers and other institutional investors to executive pay may be influenced by their own interests and background, given that the asset management industry is itself very high paid.

In addition, the proportion of UK company shares held by UK beneficiaries has declined significantly over time, with the majority of UK shares now held by overseas investors. The proportion of UK shares held directly by UK pension funds fell from almost one in three in 1990 to less than one in fifty (1.8 per cent) in 2020. If indirect ownership is included, UK pension funds hold under six per cent of UK shares. The proportion of UK shares held by overseas investors rose from 12 per cent in 1990 to a record 56.3 per cent in 2020[7]. This means that the extent to which views and values of the UK public may influence UK companies via their shareholders is significantly reduced. It also means that redistributing profits from dividends to wages would have little impact on UK pension schemes[8].

There is however a more fundamental question that should be asked: what is the justification for the prioritisation of shareholder interests and rights within company law and corporate governance? Shareholder primacy originates from a time when companies needed to attract funds from wealthy individuals in order to expand and invest; shareholder rights gave those wealthy individuals some influence over how their funds were used and protection against misuse by company managers. This quaint picture no longer holds (if it ever did); only a minority of investors are now individuals, but more importantly the vast majority of stock market activity is the buying and selling of second-hand shares, with companies only raising funds from the stock market at floatation or in circumstances such as rights issues, which are rare. Only a fraction of the money invested in the stock market ever reaches company coffers. The transfer of funds is overwhelmingly the other way round, with billions of pounds paid each year from companies to their shareholders. This reinforces the importance of the question above.

In more recent debate, there are two main justifications given for the shareholder prioritisation and rights: risk and interests.

Proponents of shareholder primacy often argue that of all company stakeholders, investors bear the greatest risk in companies, in particular in relation to corporate failure. This argument is belied by reality, in which most shares are held by asset managers and other institutional investors, who hold shares in hundreds of companies precisely to diversify their risk. Very few, if any, investors will ever have their whole livelihood tied up in one company. Whereas the workforce invests their labour, skills and commitment in the company they work for and if that investment goes wrong will pay a heavy price, losing their livelihood and security and sometimes their home and health. Few people can walk from one job to another and all too often redundancy leads to severe hardship caused by abrupt falls in income, followed by lower levels of future earnings and sometimes an end to working life. Suppliers too can suffer serious and at times fatal damage if a company goes under leaving its debts unpaid. If exposure to risk determines governance rights in companies, the workforce and major creditors should take over from shareholders.

The fundamental question of the question of whose interests companies should serve was examined by the Company Law Review of 1999 to 2002. It argued[9] that in the long-run the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders converge, as both are served through successful companies and that the prioritisation of shareholder interests would therefore not hurt other stakeholders in the long-run but would help give directors focus in the short-term. It concluded that shareholder primacy should remain in place, but added the requirement that directors must consider employee and other stakeholder interests and related reporting requirements, creating what it called ‘enlightened shareholder value’.

This argument too is belied by the reality of today’s stock market. The average holding period of UK shares has declined from around six years in 1950 to less than six months[10], driven down in part by high-frequency traders whose interest is aligned to tiny movements in share prices, rather than any long-term value drivers of a company. However, many so-called long-term investors also rely increasingly on share trading, rather than sustainable dividends accrued through long-term share ownership, to generate economic returns. A strategy based on share trading, even if based on longer holding periods than for high-frequency traders, nonetheless means the investor’s economic interest lies in strategies to raise the company’s share price, rather than strategies to invest for long-term sustainable growth. In this scenario, the interests of investors do not converge with those of other stakeholders because they are no longer tied to the long-term success of the company but instead to short-term movements in its share price.

The UK’s system of mergers and takeovers, or the market for corporate control, provides another incentive for companies to pursue strategies to keep their share price high, rather than invest in long-term, organic growth. In contrast to other European or US companies, UK companies are uniquely vulnerable to hostile takeover bids. It is common for European companies to have significant chunks of shares held by a family, bank or another company, without whose agreement a hostile takeover will fail, while many US companies adopt so-called ‘poison pills’ - provisions to protect themselves against unwanted takeovers - which are not legal in the UK. For UK companies with their dispersed shareholdings, the best way of protecting themselves against a hostile takeover is to keep their share price high so that a takeover will be too expensive for bidders to contemplate. This creates another powerful incentive for UK companies to adopt strategies to raise their share price.

One way of doing this is to pay high dividends. And there is strong evidence that UK companies pay dividends that are not justified by company performance. As set out above, the share of profits going to dividends has risen steeply over time. In addition, analysis[11] of the FTSE 100 between 2014 and 2018 carried out by the High Pay Centre and TUC found that in 27 per cent of cases returns to shareholders were higher than the company’s net profit, including 7 per cent of cases where dividends and/or buybacks were paid despite the company making a loss. In 2015 and 2016, total returns to shareholders came to more than total net profits for the FTSE 100 as a whole.

If shareholder and company interests were aligned, when profits fall, so should shareholder returns. Our research[12] found that this is not the case and that profits varied significantly more than returns. Total profits ranged from £53 billion in 2015 to £150 billion in 2017, a variation of £97 billion, with a fall between 2014 and 2015 and a sharp rise in 2017. Returns to shareholders ranged from £74bn in 2015 to £122 billion in 2018, a variation of £48 billion – less than half the variation in net profits. This contradicts the idea that shareholders are exposed to the greatest risk of all business stakeholders, as it suggests that they can expect consistent returns, regardless of profitability.

The conclusion that directors prioritise shareholder returns to the detriment of long-term company success and wider economic resilience is backed up by other research.

An academic study[13] of 182 companies in the FTSE 350 from 2009 to 2019 ranked companies by their ratio of shareholder returns to net income. It found that the top 20 per cent of companies (in terms of shareholder returns to net income) paid out 178 per cent of their net income to shareholders over the period.

Compared with the other companies in the sample, the top 20 per cent of companies (in terms of shareholder returns to net income) also registered:

· the lowest productivity increases

· the lowest growth in R&D

· the lowest performance in terms of profitability and investment returns

· the highest debt to equity ratio, and

· the highest goodwill to shareholder equity ratio.

These results suggest that these companies are paying dividends funded by borrowing, rather than funded by sustainable profits generated by investing in organic growth.

A study[14] by Queen Mary University London, Sheffield University and Copenhagen Business School showed that in 2019 over a quarter of the FTSE 100 in the UK, S&P 500 in the US and S&P Europe 350 in Europe had paid out more in returns to shareholders than they had generated in net income in their previous accounting year, leaving them more vulnerable to the impact of the pandemic and the shutdown. As the study’s author argued:

“Their focus on short-term payouts is going to make the recession even deeper, costs to governments much larger and will extend the need for central bank intervention.”

Research[15] for the Bank of England found that 80 per cent of publicly owned firms agreed that financial market pressures for short-term returns to shareholders had been an obstacle to investment. The most important reason for under-investment was a constraint on using profits for investment purposes, with three quarters of firms rating distribution to shareholders (including dividends and share buybacks) and purchase of financial assets (including mergers and acquisitions) ahead of investment as the most important use of internally generated funds.

There is an overwhelming case for reforming shareholder primacy and giving other stakeholders, notably the workforce, stronger rights in relation to corporate governance.

Corporate structures, complexity and business models and outsourcing

Over the last ten to twenty years, there has been an increase in corporate complexity and the development of corporate structures and business models that act to facilitate financial extraction from companies and weaken workforce power.

Corporate complexity

Many large companies, both listed and private, operate through a complex web of corporate structures and holding companies. This has implications for corporate governance and for employment relationships.

Operating through layers of registered companies with slightly varying names and sometimes multiple holding companies can damage transparency, making it harder to scrutinise company information and accounts and work out exactly where monies are earned, tax is due and so on. Importantly for corporate governance, it can also obscure where decisions are taken and who is legally accountable for them. For example, directors’ duties require directors to take employee interests and other stakeholder relationships into account in decision making; but within a complex corporate structure, the directors who are actually driving decisions may not be those who are running the part of the organisation with responsibility for the workforce. Thus an important legal requirement and the only right that workers currently have under company law is effectively side-stepped.

At times corporate structures may become so complex that company directors simply do not understand exactly what is going on. This would appear to be part of the problem leading to the sudden demise of Carillion plc, which consisted of over 300 companies. It seems highly likely that this array of subsidiaries contributed to directors failing to understand the company’s true financial position. It is important to note that Carillion’s structure does not appear to have given its subsidiary companies any protection against their parent company’s collapse. It is also important to note that however dysfunctional Carillion’s corporate structure was, it was perfectly legal for it to be set up in that way[16].

While there can be good reasons for operating with structures that include holding companies and subsidiaries, there are too many instances where corporate complexity appears to have the effect of obscuring transparency, muddying accountability and blunting the effectiveness of corporate decision-making. We need further research and an open public debate about the purpose and effects of corporate complexity and consideration of reforms to ensure that corporate structures are compatible with the public interest and an inclusive economy.

Private equity and other private ownership

The ownership outright of companies by private equity funds and other private companies exposes the problems of the UK’s current corporate governance system. While it is not universal, it is well established that some private equity owners and other private owners extract significant economic value from their portfolio companies, leaving the latter more economically vulnerable and with less money for wages, training and other investment. A study[17] of the impact of private equity on the care sectors of Germany, France and the UK identified the following strategies that it terms the private equity toolbox:

- The use of debt to buy companies, which is then transferred to the acquired companies, leading to the acquired companies having to pay back high interest rate loans to their parent company.

- Sale and leaseback arrangements, whereby the acquired company’s buildings or real estate is sold to generate funds for the parent company, leaving the acquired company to pay rent, often to another company connected to the private equity owner.

- Profits transferred to parent companies in offshore financial centres, reducing tax and transparency.

- The intensification of work for staff and poorer outcomes for care home residents.

While there is debate on how widespread these strategies are, few would dispute that they are used to some extent by the private equity industry and indeed by other private owners. They demonstrate a clear case of corporate owners adopting strategies that destroy and extract, rather than create, value for the acquired company. Again, this demonstrates the weaknesses of our current system of corporate ownership and governance. None of these strategies is in itself illegal. And nor are directors’ duties a bar to adopting value-destroying practices. Company directors are required by company law to promote the success of the company for the benefit of shareholders – which in this case is the private equity fund or other private owner. The law therefore allows corporate owners to treat the company they own as though it was a pen or pencil that can be simply discarded or broken at will.

This is entirely wrong, both morally and economically, and against the public interest. A company is not the equivalent to a pencil or some other small thing that can be legitimately disposed of without consequences to anyone but the owner. It embodies productive capacity, innovation and skills, its workforce, suppliers and customers and the law should not give a corporate owner the right to destroy this. The law should be changed to address this.

Specific work to look at how to tackle the strategies used by private equity is needed, and will be the subject of future TUC work. But the existence of these practices further illustrates why shareholder primacy not fit for purpose.

Business models based on fragmented employment relationships and insecure work

There has been a significant increase in the use of business models that weaken or disrupt completely the employment relationship between workers and the organisation that ultimately benefits from their work. This leads to organisations that reap the economic benefit from work having little or no responsibility for those whose work has contributed to their operations and success.

The TUC’s 2018 report Shifting the risk[18] explored this area in detail and set out the main ways in which organisations are transferring accountability for employment relationships to third parties:

- Outsourcing - contracting out tasks, operations, jobs or processes to an external contracted third party for a specific period. Industry data[19] suggests that companies providing outsourced services employ 3.3 million people across the UK, but TUC research below suggests the true figure may be far higher.

- Franchising – a franchisor grants a licence, which entitles the franchisee to own and operate their own business under the brand, systems and business model of the franchisor. Franchised businesses employ over 615,000 people in the UK[20].

- The use of labour market intermediaries to source workers – using recruitment agencies, umbrella companies and personal service companies means organisations can avoid the employment law and tax obligations of directly employing their workforce. We estimate that there are approximately 2 million people employed via labour market intermediaries.

- Developing complex supply chains – hiring additional individuals or companies (subcontractors) to help complete a project, and transferring liability to organisations further down the supply chain.

Recent polling for the TUC suggests that over one third of workers consider themselves outsourced workers. Polling carried out by Britain Thinks[21] set out a definition of outsourcing and asked workers whether based on that definition[22] they believed they were an outsourced worker. The research found that:

- 36 per cent of workers consider themselves to be an outsourced worker, most of whom work for another business

- 52 per cent of workers in London consider themselves to be an outsourced worker

- Over half of workers in construction (59 per cent), transportation and storage (52 per cent) and IT and communications (51 per cent) consider themselves to be outsourced.

This suggests that the extent of outsourcing across the economy may be much larger than previously recognised.

For the workers at the end of fragmented employment relationships, perhaps the most significant implication is that the organisation that they are directly employed by is often no longer responsible for:

- Setting the substantive terms on which they are employed. Often a company higher up the supply chain will decide the rate for the job and therefore how much workers are paid.

- Deciding what, when or how work is done. Often the end-user will oversee and direct their work.

- Ensuring that they are treated fairly in the workplace.

This makes it much harder for workers to secure their rights at work. The TUC has found a negative impact on workers, including:

- Confusion over who their employer is and who has responsibility for employment rights

- Restricted access to employment rights, linked to their non-employee employment status

- Deteriorating terms and conditions

- Breaches of basic workplace rights such as to the national minimum wage and paid holidays.

Alongside the rise in fragmented employment relationships, there has also been a significant rise in insecure work. TUC analysis[23] shows that 3.7 million people, around one in nine of the workforce, are in insecure work. This includes:

- 935,000 people on zero hours contracts

- 952,000 agency, casual and seasonal workers (but not those on fixed–term contracts)

- 1.9 million people in low-paid self-employment, who miss out on key rights and protections that come with being an employee and cannot afford to provide a safety net for when they are unable to work.

The distribution of insecure work both reflects and reinforces prevailing structural inequalities. Our research shows that one in six (14.6 per cent) of Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers is likely to be in insecure work, compared with 11.1 per cent of white workers.

The extent of insecure work rose after the financial crisis that hit in 2007. Zero hours contracts have grown from 70,000 in 2006[24] to the levels we see today. Polling for the TUC punctures the myth that these contracts offer two-way flexibility to both workers and employers. In 2021, research[25] for the TUC found that:

- more than two-thirds of zero hours contract workers (69 per cent) had had work cancelled at less than 24 hours notice;

- 84 per cent of these workers had been offered shifts at less than 24 hours notice;

- by far the most important reason for taking a zero hours role was that it was the only work available.

Insecure work has a huge impact on people’s lives. The prospect of having work offered or cancelled at short notice makes it hard to budget for household bills or plan a private life. It is also damaging to health; the Marmot Review of health inequalities found that while unemployment contributes significantly to poor health, a poor quality or stressful job can be even more damaging, concluding that “Getting people off benefits and into low paid, insecure and health-damaging work is not a desirable option”.

The Review set out five characteristics of work that evidence shows are damaging to health: job insecurity and instability; low levels of control; high levels of demand at work; lack of supervisor and peer support; and more intensive work and longer hours. These work characteristics are linked to a range of mental and physical health impacts, including depression, cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease and musculoskeletal disorders and metabolic syndrome (a combination of risk factors for diabetes and heart disease).

Unfortunately, insecure work has many of the characteristics above. Workers have reported that their medical appointments and social events often have to be cancelled at short notice[26]. Experiences of low levels of control and lack of peer and supervisor support are also borne out by our research. A separate set of polling[27] reveals that three quarters (75 per cent) of those in secure work would feel comfortable raising an issue with their manager, compared to 60 per cent of those in insecure work. There is also a ten percentage point gap in the proportion of insecure and secure workers who feel safe at work, with 73 per cent of insecure workers feeling safe compared to 83 per cent of those in secure work.

Insecure work also has the effect of further weakening worker power. If you are reliant on the whims of a boss for your next shift you are far less likely to complain about conditions, let alone ask for a pay rise. It blights the lives of millions of workers who deserve better.

Business schools promote business models that damage workers

These employment models may in part be the result of business school thinking that leads to workers losing out. A recent academic study[28] provides evidence of a link between business schools and managers adopting business models that damage workforce interests. The research finds that appointing a CEO with a business school degree leads to a decline in wage levels and in the overall labour share of the company. Within five years of appointment, wages declined by six per cent and the firm labour share by 5 percentage points in the US and by 3 per cent and 3 percentage points in Denmark, relative to other firms. The research finds that these firms do not have higher sales, output, productivity, investment or employment growth. However, worker quits increase, especially of higher skilled workers. The reduction in wages leads directly to an increase in profits, with returns on assets increasing 3 percentage points in the US and 1.5 percentage points in Denmark. In the US, the stock market values of companies rises about 5 per cent. In Denmark, there is a link with debt financing. All other things being equal, CEOs with a business school degree earn more than other CEOs.

The research also examines how firms respond to opportunities of increased export demand. At firms without business school degree CEOs, a 10 per cent increase in value added per worker is associated with a 1.9 per cent increase in wages and a 10 per cent increase in profit per worker is associated with a 1 per cent increase in wages. In contrast, there is no impact on wages at firms with business school degree CEOs.

The authors “interpret these findings as capturing the impact of management practices and values imparted by business schools and business degrees...[that] may significantly affect the priorities and approaches adopted by managers with business degrees. The first is the emphasis on shareholder values...”.

Worker power

Against this backdrop of increased emphasis on shareholder value and the rise of labour market fragmentation and exploitative business models, workers’ ability to win their share of the wealth they create has been under attack.

In contrast to shareholders, workers have no rights to voice or representation in corporate governance; indeed, other than the right for their interests to be considered by company directors, workers have no corporate governance rights at all.

It is through trade unions and collective bargaining, rather than corporate governance rights, that workers in the UK have been able to influence the decisions that affect them and bargain for fair pay and conditions at work.

However, union density and collective bargaining have declined significantly over recent decades – although it is important to note that this decline had slowed and started to reverse prior to the pandemic. Nonetheless, collective bargaining coverage remains much lower now that it was in the 1980s. In 1979, union density was 54 per cent and collective bargaining coverage was over 70 per cent; in 2021, they were 23.1 per cent and 26 percent respectively, with just 13.7 per cent of workers in the private sector protected by a collective agreement[29]. While the ONS suggests that these collective bargaining figures may be underestimates, it is clear that there has been a significant decline in collective bargaining coverage over time.

There are many reasons for the decline in union membership and collective bargaining coverage over the past four decades. Anti-trade union legislation and the dismantling in the 1980s and early 90s of much of the national and sectoral collective bargaining machinery that had been in place throughout the post-war period has played a part. This has been compounded by structural changes in the economy, and in particular the relative decline of the traditionally unionised manufacturing sector and the growth of private sector services, which has reduced the extent to which people are exposed to unions just by being at work. The significance of this industrial shift is demonstrated by recent analysis[30] showing that the decline of unions at workplace level is driven by the absence of unions at newer workplaces and not by unionised workplaces closing or union derecognition, with union recognition rates at younger establishments two-thirds the rate of older establishments (26 per cent to 39 per cent). Other changes, including the increasing proportion of people working in smaller workplaces and the sharp rise in people in insecure work and employed via agencies, have created significant practical barriers for grassroots union organising and recruitment drives.

The Trade Union Act 2016 created further barriers for unions organising and standing up for their members at work; and there are fears that the current government may place even more restrictions on union activity.

Where collective bargaining is in place, it continues to play a significant role in protecting not only pay but a whole range of working conditions that play a positive role in people’s lives[31].

Research[32] shows that workplaces with collective bargaining have higher pay, more training days, more equal opportunities practices, better holiday and sick pay provision, more family-friendly measures, less long-hours working and better health and safety. Staff are much less likely to express job-related anxiety in unionised workplaces than comparable non-unionised workplaces; the difference is particularly striking for women with caring responsibilities.

Employers benefit too. Collective bargaining is linked to lower staff turnover, higher innovation, reduced staff anxiety relating to the management of change and a greater likelihood of high-performance working practices. And society benefits. Influential organisations from the IMF to the OECD have recognised the role of collective bargaining in reducing inequality, with the OECD[33] calling on governments to “put in place a legal framework that promotes social dialogue in large and small firms alike and allows labour relations to adapt to new emerging challenges”.

Working people need new rights to enable them to come together to bargain collectively with their employer and gain a fair share of the wealth they create. The wage and cost of living crisis we are currently experiencing makes this increasingly urgent, but it is important to note that the shrinking share of wages in our economy goes back a long time and is not a new trend. The share of GDP going to wages has fallen by 10 percentage points of GDP between the post war decade to the latest decade, falling from 59.1 per cent over 1948-1957 to 49.1 per cent over 2012-2021[34]. Change is not only urgent but overdue.

There is nothing inevitable about how our economy and businesses operate: it is a result of policy choices made over decades and in some cases over centuries. Our current model of corporate governance and the distribution of rights and power within companies is damaging to workers and to long-term business success and the wider economy. Reform is necessary and urgent.

Change company law to require directors to focus on long-term company success and balance workforce and shareholder interests

At the moment, as set out above, company law requires directors to prioritise the interests of shareholders over those of other stakeholders. As this report has shown, the prioritisation of shareholder returns and interests reduces the funds available for wages and investment and encourages short-termism in decision-making.

There is strong public support[35] for the legal duties of company directors to change, with 76 per cent of workers agreeing with the following statement, compared with 5 per cent who disagreed:

“When making decisions, businesses should be legally obliged to give as much weight to the interests of their staff and other stakeholders (eg local communities) as they give to the interests of their owners or shareholders”.

Given the benefits to the workforce, other stakeholders, the company itself and wider society, it is time the law caught up with the public. Reform should rewire companies for long-term, inclusive success. To that end:

Directors’ duties should be rewritten to remove the current requirement for directors to prioritise the interests of shareholders. Directors should be required to promote the long-term success of the company as their primary aim, taking account of the interests of stakeholders including the workforce, shareholders, suppliers, customers and the local community and impacts on human rights and the environment.

A possible formulation, based on the existing wording in the Companies Act 2006 with some revisions, is set out below:

“A director of a company must act in the way s/he considers, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the long-term success of the company, and in so doing, should have regard to the need to:

i) promote the interests of the company’s workforce

ii) deliver sustainable returns to investors

iii) foster the company’s relationships with suppliers, customers, local communities and others, and

iv) take a responsible approach to the impact of the company’s operations on human rights and on the environment...”

Change ‘employee’ to ‘workforce’ in the Companies Act to require companies to report on their whole workforce, not just employees

At the moment, despite the widespread use of indirect employment relationships as set out above, companies are only required to report on their directly employed workforce – their employees. This is because the Companies Act uses the word ‘employee’ throughout.

Using the word 'employee' in the Companies Act affects all the reporting regulations that are laid using its powers. Most workforce reporting requirements stem from company law, not employment law, so without this amendment it is impossible to require companies to report on their whole workforce or on their employment model, as recommended by the Taylor Review.

Changing ‘employee’ to ‘workforce’ in the Companies Act would have the effect of broadening the scope of directors' duties and reporting requirements in the Companies Act. This means companies would have to report on and have regard to their whole workforce, rather than just their directly-employed employees as at present.

Indirect employment was much less prevalent when the Companies Act was last revised in 2006 and the word 'employee' was clearly not intended to differentiate between different parts of a company's workforce. The amendment would update the Companies Act to reflect the modern labour market.

This change has already been reflected in other corporate governance rules, including the 2018 Corporate Governance Code and the Wates Corporate Governance Principles for Large Private Companies, which both use ‘workforce’ throughout.

Unfortunately, the use of the word 'employee' has a significant impact on the quality and accuracy of company reporting. Some companies that employ a significant proportion of their workforce indirectly or through a franchising model exclude those workers entirely from their company reports, despite the latter's contribution to the company's products/services and profitability. The TUC has set out some examples of this in a previous report, which discusses this proposal and the case for it in more detail[36].

Worker directors, elected by the workforce, should comprise one third of the board at companies with over 250 staff

As set out above, in contrast to many European countries, workers currently have no corporate governance rights in the UK and a company’s workforce has no right to ‘voice’ or participation in company decision-making.

As this report has argued, of all company stakeholders, the workforce is generally the most affected by the priorities and decisions of company boards. It is a matter of justice and democracy that they should have a voice in those decisions.

Worker directors are the norm across most of Europe. In 19 out of 27 EU Member States plus Norway (i.e. 19 out of 28 European countries) there is some provision for worker directors on company boards, and in 13 of these countries the rights are extensive in that they apply across much of the private sector[37]. Research[38] shows that countries with strong workers’ participation rights perform better on a whole range of factors, including R&D expenditure and employment rates, while also achieving lower rates of poverty and inequality.

There is strong evidence that more diverse boards make better decisions. The TUC supports measures to promote greater gender and ethnic diversity on boards. We also believe that measures to include workers directors on company boards would improve the quality of broad decision-making.

Worker directors would bring people with a very different range of backgrounds and skills into boardrooms, helping to challenge ‘groupthink’. It is clear from the minority of UK companies with worker directors and from evidence from countries where worker directors are common that bringing the perspective of an ordinary worker to bear on boardroom discussions is particularly valued by other board members.

Workers have an interest in the long-term success of their company and their participation would encourage boards to take a long-term approach to decision-making. They would bring direct experience to bear on the important area of workforce relationships, a key area for company success.

The 2018 Corporate Governance Code now includes provisions on engagement with the workforce, with worker directors one of the options included. However, only four companies to date have chosen to comply with the Code by appointing worker directors (making a total of five, as the FTSE 250 company FirstGroup plc has had an employee director elected by the workforce since the company’s inception in 1989). The option most commonly chosen by companies has been to designate a non-executive director as responsible for ensuring the workforce is considered in the boardroom.

Research[39] published by the Financial Reporting Council on how companies have implemented the new Code requirements found that where worker directors have been appointed they are valued and working well. In contrast, the research found that “in broad terms, most of the weakest and least substantive practices were those relying solely on NEDs [non-executive directors], or on underdeveloped ‘alternative arrangements’”.

The TUC believes that elected worker directors should comprise one third of the board at all companies with 250 or more staff. We have set out more detail on the case for workers directors and our proposals for implementation in an earlier report[40].

Restore power to workers by boosting collective bargaining

Giving workers stronger rights to organise collectively in unions is key both to raising pay and working conditions and giving workers more say over their working lives. The absence of a collective approach to driving up employment standards has left workers unable to fight for a fair share of the wealth they create or protect themselves from the impact of exploitative business models as set out above.

This report has set out above the benefits the collective bargaining brings to workers and to employers. Collective bargaining is a public good that promotes higher pay, better training, safer and more flexible workplaces and greater equality.

At the moment, the process for establishing union recognition and collective bargaining is complex and it is too easy for employers to block workers’ efforts to organise by refusing to allow unions to access workplaces, punishing workers who stand up for their rights and adopting strategies such as making alterations to a proposed bargaining unit to undermine work building support for the union. We need new rights[41] to make it easier for working people to negotiate collectively with their employer.

· Unions should have access to workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership and collective bargaining (following the system in place in New Zealand).

· The process for establishing union recognition and collective bargaining should be simplified, including awarding recognition if unions win a simple majority in a ballot and reducing the threshold for triggering the statutory recognition scheme to 2 per cent of the members of a bargaining unit to bring it into line with the threshold for rights to collective consultation. The exemption for organisations of 21 of fewer from the statutory recognition scheme should be removed, extending the right to seek union recognition to around six million workers.

· The scope of collective bargaining rights should be expanded to include all pay and conditions, including pay and pensions, working time and holidays, equality issues (including maternity and paternity rights), health and safety, grievance and disciplinary processes, training and development, work organisation, including the introduction of new technologies, and the nature and level of staffing.

· We need Fair Pay Agreements agreed by unions and employers to set minimum pay and conditions across sectors. Starting in sectors characterised by low pay and poor working conditions, we need to create new bodies for workers and employers to come together to negotiate and agree minimum standards for the sector. Sectoral bargaining is critical to driving up wages and conditions in sectors with poor employment practices that employ and will continue to employ large numbers of people. Sectoral Fair Pay Agreements would protect workers from exploitation and prevent good employers from being undercut by employers with poor employment practices. Social care and hospitality, sectors characterised by poor pay and conditions and experiencing labour shortages, should be priority sectors for rolling out sectoral bargaining and Fair Pay Agreements.

Address corporate complexity and exploitative business models by giving workers rights to scale up bargaining across business operations

Organisational size and structure should not prevent workers from having a voice at work. In large organisations with complex structures, it can be very difficult to establish collective bargaining across the organisation as a whole. This hampers the ability of the workforce to negotiate effectively with their employer, as workers with union recognition for their workforce group or workplace are told that pay and conditions are set across the organisation as a whole, but are not able to bargain for the whole workforce.

Workers and unions need to be able to scale up bargaining rights to prevent corporate complexity and exploitative business models acting as a barrier to workforce voice and representation and a fair deal at work. In large, multi-site organisations, unions and workers that have recognition within one bargaining unit should have the ability to scale up their bargaining rights across the organisation without reaching the 2 per cent membership threshold within the additional unit or workforce group.

Where workers have union recognition at one workplace within a multi-site organisation or at one bargaining unit in a larger organisation, the union should have the right to:

· contact workers at another site or bargaining unit to promote union membership

· ballot a wider group of workers within the organisation, defined on the basis of geographic, occupational or organisational factors, to offer union recognition and a collective bargaining agreement without reaching the 2 per cent membership threshold within the additional bargaining unit or workforce group.

Tackle fragmented employment relationships by introducing strict joint and several liability for core employment rights in UK supply chains

To prevent fragmented employment relationships driving down pay and conditions, we need to restore accountability along supply chains so that organisations cannot simply wash their hands of responsibility for those whose work contributes to their products or services. Put simply, organisations should have a greater legal responsibility for those who work for them.

We need to move to move towards a system of strict joint and several liability for core employment law standards so that organisations have a legal responsibility to protect basic workplace rights for workers in their UK supply chain[42].

As a first step, the TUC proposes that workers should be able to bring a claim for unpaid wages, holiday pay and sick pay against any contractor above them in the supply chain.

ANNEX: NOTES ON DATA SOURCES

The comparisons between dividends and pay use ONS data sources including National Accounts:

· wages growth is calculated from the average weekly earnings (AWE) total pay measure (ONS code KAB9)

· dividends are taken from the sector accounts for the private non-financial corporation sector, as one element of property income paid (ONS code NETZ).

Most results are simply comparisons of annual growth rates for nominal figures. Real terms figures are derived using CPI (ONS code D7B7).

Current ONS published and readily available data for both earnings and dividends extends back to only 2000 and 1987 respectively. The analysis therefore relies on the widely used Bank of England record of historical data for pay ahead of 2000.

Cash figures for gain in dividends and loss in pay relative to inflation are derived based on a projection for 2022 prices, to be consistent with wider analysis for Congress 2022.

The analysis focuses mainly on the period before the pandemic (i.e. up to and including calendar year 2019), because of distortions likely to both measures as a result of methodological and behavioural issues – meaning the AWE[43] is likely overstating pay inflation and dividends have been erratically low.

Wages and dividends 1987-2019

|

|

Dividends growth (annual average, %) |

Wages growth (annual average, %) |

Ratio: dividends /wages |

Memo: CPI inflation (annual average, %) |

Real dividends growth (annual average, %) |

Real wages growth (annual average, %) |

|

1987-2008 |

10.4 |

5.2 |

2.0 |

2.8 |

7.4 |

2.4 |

|

2008-2019 |

6.3 |

1.9 |

3.2 |

2.2 |

4.0 |

-0.3 |

UK investment (gross fixed capital formation) figures (in Figure 6) are also from the sector accounts for the private non-financial corporation sector.

For the international comparison of investment on Figure 7, country (G7) figures for Gross Fixed Capital Formation and Gross Domestic Product are taken from Dataset 1 of the National Accounts section of the OECD stats database: https://stats.oecd.org/. These include investment by governments and households as well as the corporate sector, and hence the coverage is broader than the UK figures for the private non-financial corporation sector used in Figure 6.

[1] Michael O'Dwyer (2022) KPMG hit with half of UK accounting fines as penalties reach new record Financial Times 28 July 2022 available at: https://www.ft.com/content/73e48574-673a-4725-9b78-ba940a8060f5

[2] PIRC analysis of company voting results

[3] Greenpeace (November 2021) Accountable Shareholder votes on auditor appointments Briefing by Greenpeace UK available at: https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Accountable-Shareholder-votes-on-auditor-appointments.pdf

[4] High Pay Centre and TUC (August 2022) UK CEO Pay report 2021 available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/uk-ceo-pay-report-2021

[5] Excluding bonuses

[6] High Pay Centre (May 2022) High Pay Centre Analysis of FTSE 350 pay ratios available at: https://highpaycentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/STA0422803002-001_aFFT-Pay-Ratios-Report_0522_FINAL_v4.pdf

[7] Office for National Statistics (2015 and 2020), Ownership of UK quoted shares: 2014, published 2015 and Ownership of UK quoted shares: 2020, published 2022 available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/investmentspensionsandtrusts/bulletins/ownershipofukquotedshares/2020

[8] TUC, Common Wealth and the High Pay Centre (2022) Do dividends pay our pensions? available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/do-dividends-pay-our-p…

[9] Company Law Review (2000) Modern Company Law for a Competitive Economy - Developing the Framework

[10] Andrew Haldane (2015) Who owns a company? Speech by Mr Andrew G Haldane, Executive Director and Chief Economist of the Bank of England, at the University of Edinburgh Corporate Finance Conference, Edinburgh, 22 May 2015 https://www.bis.org/review/r150811a.pdf

[11] TUC and High Pay Centre (2019) How the shareholder-first business model contributes to poverty, inequality and climate change A briefing note from High Pay Centre and the TUC available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/how-shareholder-first-business-model-contributing-inequality

[12] Ibid

[13] Colin Haslam, Adam Leaver, Richard Murphy, Nick Tsitsianis (29 June 2021) Productivity Insights Network Report Assessing the impact of shareholder primacy and value extraction: Performance and financial resilience in the FTSE 350 available at:

https://productivityinsightsnetwork.co.uk/app/uploads/2021/06/PIN-Report-29-6-21-FINAL.pdf

[14] Adam Leaver et al (2020) Against Hollow Firms: repurposing the corporation for a more resilient economy, Sheffield University Centre for Research on Accounting and Finance in Context

[15] Sir Jon Cunliffe (2017) Are firms underinvesting - and if so why? Speech to the Greater Birmingham Chamber of Commerce, 17 February 2017

[16] TUC (2018) What lessons can we learn from Carillion – and what changes do we need to make? available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/what-lessons-can-we-le…

[17] Bourgeron, Théo; Metz, Caroline; Wolf, Marcus (2021): They don't care – How financial investors extract profits from care homes, Berlin: Finanzwende/Heinrich-Böll-Foundation

[18] TUC (2018) Shifting the risk Countering business strategies that reduce their responsibility to workers - improving enforcement of employment rights available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/shifting-risk

[19] BSA (2022) Letter to Chancellor Ahead of Spring Statement 2022 available at https://www.bsa-org.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Business-Services-As…

[20] BSA (2017) Annual Review: Connecting People and Places available at https://www.bsa-org.com/2017-bsa-annual-review-connecting-people-places/

[21] BritainThinks conducted an online survey of 2,198 workers in England and Wales between 3rd – 11th August 2022, based on a nationally representative sample

[22]‘Outsourcing' is the business practice of hiring another business or individual worker/s from outside a company to perform services or create goods that are a core part of the company's operations. For example, Company X's cleaning staff are not employed by Company X, but by Company A, a company or agency that supplies cleaners, or are self-employed. Company X has outsourced its cleaning, and the cleaners are outsourced workers. Outsourcing is common in many industries and can affect a wide range of jobs. Often employers outsource specific roles such as cleaning, catering, and security and IT, or whole areas of a service such as back office, customer support or local authority rubbish collections. Based on this definition, would you consider yourself an outsourced worker?

[23] The total number in ‘insecure work’ includes (1) agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed – term contracts, (2) workers whose primary job is a zero-hours contract, (3) self-employed workers who are paid less than the National Living Wage (£9.50). Data on temporary workers and zero-hour workers is taken from the Labour Force Survey (Q4 2021). Double counting has been excluded. The minimum wage for adults over 23 is currently £8.91 and is also known as the National Living Wage. The number of self- employed working people aged 23 and over earning below £9.50 is 1,860,000 from a total of 3,430,000 self-employed workers in the UK. The methodology is slightly different to last year as previous analysis looked at self-employed aged over 25, and the age threshold has now changed to 23. The figures come from analysis of data for 2020/21 (the most recent available) in the Family Resources Survey and were commissioned by the TUC from Landman Economics. The Family Resources Survey suggests that fewer people are self-employed than other data sources, including the Labour Force Survey.

[24] TUC (2016) Living on the Edge: The rise of job insecurity in modern Britain available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/living-edge

[25] 2021 data: GQR Total sample n=2523, including oversamples of BME workers and people on Zero-Hours Contracts. Fieldwork: 29th January – 16th February 2021 Cited in TUC (2021) Jobs and recovery monitor - Insecure work available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-monitor-insecure-work

[26] TUC (2018) Living on the Edge available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/living-edge-0

[27] Polling by BritainThinks for the TUC. All respondents working full / part time May 2021 (n=1972), Nov 2020 (n=2,182); = Insecure (n=110); Secure (n=1851). BritainThinks’ definition of insecure workers does not include the self-employed.