Do dividends pay our pensions?

This report examines who benefits from shareholder returns and the extent to which dividend payments from UK companies are a significant source of income for UK pension funds.

There is increasing public interest in the rising amount of money UK companies pay to their shareholders through dividends and share buybacks and the potential opportunity cost – in terms of workforce wages, investments in R&D and building resilience against external shocks, such as COVID 19.

Research shows that:

- Dividends have risen as a share of pre-tax profits at FT350 companies between 1997 and 2020, while investment has fallen over the same period;

- Shareholder returns at the FTSE 100 grew by 56 per cent between 2014 and 2018, while average earnings grew by just 8.8 per cent (both nominal); and

- It is relatively common for companies to pay dividends that exceed their total profits; this happened in 27 per cent of cases in the FTSE 100 between 2014 and 2018.

One of the justifications given for high levels of dividend payments is that ‘they pay our pensions,’ because people’s pension savings are invested in the stock market. This report examines the extent to which this is the case and who really benefits from shareholder returns.

Our analysis shows that only a tiny proportion of UK dividends and buybacks accrue to UK pension funds.

Analysis of official statistics shows that the proportion of UK shares directly held by UK pension funds fell from almost one in three in 1990 to less than one in 25 by 2018 – a decline of over 90 per cent. Most UK shares are now held by overseas investors. The proportion of UK shares owned by overseas investors rose from 12 per cent in 1990 to 55 per cent in 2018.

In addition to direct share ownership, some pension funds will own shares indirectly through pooled funds controlled by insurance companies and asset managers. Examining the data on this, we conclude that in total UK pension funds own directly or indirectly under six per cent of UK shares.

The returns that do accrue to pension savers are very unequally allocated and disproportionately benefit a wealthy minority.

The distribution of private pension wealth in the UK is highly unequal. The richest twenty per cent of UK households by income own 49 per cent of pension wealth in the UK. Although auto-enrolment has given more low-paid workers access to a workplace 3 pension, participation remains strongly correlated to income, with just 41 per cent of low-paid private sector employees working full-time belonging to a pension scheme.

In reality, the poorest pensioners depend largely on the state pension, rather than private (personal or occupational) pension savings, for their income in retirement. For many pensioners, and in particular the poorest, corporation tax is more important than dividends in terms of the contribution of corporate Britain to their pensions.

Individual share ownership is even more unequally allocated than pension fund wealth.

Looking at direct share ownership by individuals, the richest one per cent of households own 39 per cent of total share-based wealth – almost as much as the poorest 80 per cent combined.

The costs of financial intermediation reduce still further the contribution that shareholder returns make to pension funds.

The costs of financial intermediation absorb a slice of shareholder returns before they reach pension funds and other beneficiaries. Most shareholdings are managed by professional asset managers - a market review by the Financial Conduct Authority found that asset managers typically charge around 0.9 per cent of assets under management on an annual basis for an actively managed fund, while typical profit margins for the industry are 35 per cent. The average earnings threshold for the highest-paid quarter of employees at firms in the investment banking and brokerage sector is £140,000.

An issue that affects pension funds in particular is the number of costs and charges that must be borne across a complex investment chain; a 2014 DWP consultation identified a non-exhaustive list of 26 different costs and fees, including advice, professional services, administration, banking and depository fees and transaction costs. These high costs and multiple charges mean that even to the extent to which pension funds do hold UK shares, this is not an efficient way of sharing the value created by UK companies with working people.

Conclusions

The findings of the report inarguably demonstrate a minimal and diminishing link between the fortunes of the UK’s largest companies and the pensions of working people. UK pension funds account for a small and declining proportion of UK shareholdings. Individual shareholdings are overwhelmingly concentrated amongst the very rich.

Yet the priority placed upon shareholders in the UK’s corporate governance system encourages companies to prioritise shareholder returns above wages or long-term investment. And executive pay is often linked to levels of shareholder returns, creating a direct incentive for company directors to pay dividends even when not justified by performance.

It is time for this to change so that working people benefit fairly from the success of the companies they work for and claim a fair share of the value they create. This will require corporate governance reform alongside policies to promote collective bargaining.

There is strong public support for the legal duties of company directors to change.

76% of workers agreed with the following statement (compared with 5% who disagreed):

“When making decisions, businesses should be legally obliged to give as much weight to the interests of their staff and other stakeholders (eg local communities) as they give to the interests of their owners or shareholders”.

Given the benefits to the workforce, other stakeholders, the company itself and wider society, it is time the law caught up with the public.

Proposals for reform

- Directors’ duties should be rewritten to remove the current requirement for directors to prioritise the interests of shareholders over those of other stakeholders. Directors should be required to promote the long-term success of the company as their primary aim, taking account of the interests of stakeholders including the workforce, shareholders, suppliers, customers and the local community and impacts on human rights and the environment.

- Worker directors, elected by the workforce, should comprise one third of the board at all companies with 250 or more staff.

- Companies should be required to report on their spending on wages, R&D, training, dividends, share buybacks and executive pay over a rolling ten year period so that all stakeholders can see how these amounts have changed over time.

- Companies should be required to report on the average annual percentage pay rise (or otherwise) per worker tracked against the annual percentage rise in total shareholder returns over a rolling ten year period.

- Unions should have access to workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership and collective bargaining (following the system in place in New Zealand).

- Workers should have new rights to make it easier to negotiate collectively with their employer.

- New bodies for unions and employers to negotiate across sectors should be established, starting with hospitality and social care.

Background

There is increasing interest in the impact that the scale of returns generated by large corporations for their shareholders in the form of dividend payments and share buybacks is having on efforts to improve the UK’s economic productivity, reduce inequality and respond rapidly and fairly to the climate and nature emergency.

Research from HPC and the TUC shows that dividend payments and share buybacks made by the UK’s FTSE 100 companies totalled £442bn between 2014 and 2018, swallowing up over 80% of the net profits recorded by those companies over the period. 1 For context, this is almost as much as the total £470bn 2 value of defined contribution (DC) pension saving in the UK. 3 In 27% of cases, the returns to shareholders exceeded the profits made by these companies. In 2020, despite the pandemic, aggregate dividend payouts by FTSE 350 companies represented some 90% of aggregate pre-tax profit - the outcome of more than two decades of upward drift which has seen shareholders reaping an increasing share of corporate profits, even as UK corporate debt has seen all-time highs in recent years and real wages have stagnated. 4

This is obviously a vast sum of wealth – and the choice to liquidate it in the form of dividends and buybacks, prioritising shareholders over critical stakeholders, has potential opportunity costs in terms of:

- the resilience of those companies in the face of external shocks, such as the Covid-19 crisis;

- their long-term investment in innovation, technology and environmental sustainability;

- the pay and working conditions of their workers; while FTSE 100 returns to shareholders rose by 56% between 2014 and 2018, the median wage for UK workers increased by just 8.8% (both nominal).

A study by Queen Mary University London, Sheffield University and Copenhagen Business School showed how in 2019 over a quarter of the FTSE 100 in the UK, S&P 500 in the US and S&P Europe 350 in Europe had paid out more in returns to shareholders than they had generated in net income in their previous accounting year, leaving them more vulnerable to the impact of the pandemic and the shutdown. As the study’s author argued:

“Their focus on short-term payouts is going to make the recession even deeper, costs to governments much larger and will extend the need for central bank intervention.” 5

Research for the Bank of England found that 80 per cent of publicly owned firms agreed that financial market pressures for short-term returns to shareholders had been an obstacle to investment.6 The most important reason for under-investment was a constraint on using profits for investment purposes, with three quarters of firms rating distribution to shareholders (including dividends and share buybacks) and purchase of financial assets (including mergers and acquisitions) ahead of investment as the most important use of internally generated funds.

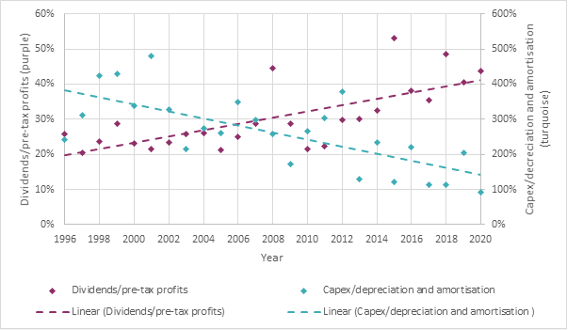

Figure 1: Dividends vs investment as a proportion of pre-tax profits in the FTSE 350 over time 7

- 1 High Pay Centre/Trades Union Congress, How the shareholder first business model contributes to poverty, inequality and climate change, 2019

- 2 The Investment Association, Investment Management Survey 2020-2021

- 3 DC pensions are the most common form of retirement saving vehicle for current UK workers and make up about 1/8 of total pension wealth (see Pension funds share ownership section below).

- 4 Adrienne Buller and Benjamin Braun (2021) 'Under new management: Share ownership and the growth of UK asset manager capitalism', Common Wealth, https://www.commonwealth.co.uk/reports/under-new-management-share-owner…

- 5 Sheffield University Centre for Research on Accounting and Finance in Context, Against hollow firms: repurposing the corporation for a more resilient economy, 2020

- 6 Sir Jon Cunliffe, Are firms underinvesting – and if so why? Speech to the Greater Birmingham Chamber of Commerce, 17 February 2017

- 7 Adrienne Buller and Benjamin Braun (2021) 'Under new management: Share ownership and the growth of UK asset manager capitalism', Common Wealth, https://www.commonwealth.co.uk/reports/under-new-management-share-owner…

It has been argued that the preference in the UK asset management sector for ‘equity income funds’, which prioritise dividends over any other kind of return and have been described as “a uniquely UK phenomenon”, increase this pressure.8 This is reflected in corporate behaviour; as figure one above shows, over a twenty period, as dividends as a percentage of pre-tax profit have risen, investment - measured as the ratio of Capital Expenditure to Depreciation and Amortization - trended downward, contributing to the UK’s poor productivity performance.

International analyses demonstrate the potential repercussions for workers’ wages. A 2018 research paper in the US by the Roosevelt Institute and the National Employment Law Project found that prominent companies in low wage industries could have funded annual pay increases of up to $18,000 dollars per worker with the money they dedicated to share buybacks over the period studied. 9

Who benefits from shareholder returns?

There is therefore a vigorous debate about whether dividends and buybacks should be subject to greater oversight, either through direct regulation or corporate governance reform. And more broadly, the balance between shareholder returns and wages, combined with companies paying dividends when not justified by company performance, raise serious questions about our corporate governance system and the priority it places on the interests of shareholders.

The question of who ultimately benefits from these huge transfers of wealth from businesses to their shareholders is a hugely important part of this debate, with profound implications particularly in respect of incomes, living standards and inequality.

It is regularly asserted that dividend pay-outs “pay our pensions” or supplement the retirement provisions of ordinary savers. When a number of companies began to cut or withhold dividend payments at the beginning of the Covid crisis, the Daily Mail headline suggested the cuts were ‘set to cost pension funds and savers nearly £85bn.’10 The investment firm AJ Bell suggested that dividend cuts would hit people “trying to earn a good return on their hard-earned savings.”11

Similarly, the impact on pensions savings has been used to justify opposition to public ownership of utilities – for example, the Global Infrastructure Investor Association claimed that 118 pension funds are invested in UK infrastructure projects, including privatised utility companies.12 However, the fact that pension funds have some investments in UK companies does not mean that they represent the majority or even a substantial proportion of the share ownership of corporate Britain. The research in this report set out to establish the extent to which dividend payments and share buybacks accrue to ordinary British pensioners and/or individual low- and middle- income investors and how representative UK company shareholders are of the UK population as a whole.

Pension funds' share ownership

Figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) highlight the decline in pension funds’ investment in UK equities, meaning that the proportion of ‘corporate Britain’ owned by UK pension funds has also dramatically decreased.

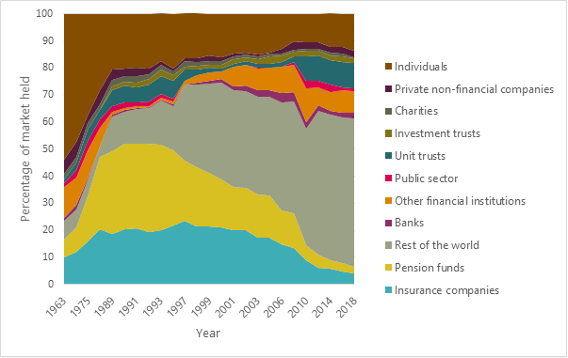

Figure 2: Pension fund ownership of UK-quoted shares 13

- 8Financial Times, London is becoming the Jurassic Park of stock exchanges, 1 December 2021

- 9 Roosevelt Institute, Curbing Stock Buybacks: A Crucial Step to Raising Worker Pay and Reducing Inequality, 2018

- 10 Daily Mail, Coronavirus crisis looks set to cost pension funds and savers nearly £85bn in lost dividends, 3 May 2020

- 11 AJ Bell, Shell dividend cut to hurt investors across the UK, Reckitt doing better than expected, and the FTSE continues to push forward, 30 April 2020

- 12 Global Infrastructure Investor Association, Millions of UK pension savers supporting regional and national infrastructure, 26 March 2019

- 13 Office for National Statistics, Ownership of UK quoted shares: 2018 and Ownership of UK quoted shares: 2014, published 2020 and 2015

The figures show that the proportion of shares owned by UK pension funds fell from almost one in three (32.4 per cent) in 1990 to less than one in 25 (2.4 per cent) by 2018 – a decline of over 90 per cent. The majority of shares in UK companies are actually held by overseas investors, as shown in figure 2. The proportion of UK shares owned by overseas investors rose from 12 per cent in 1990 to 55 per cent in 2018.

It should be noted that some of the shares in unit trusts will ultimately be owned by pension funds and some of the shares controlled by insurance companies will be defined contribution pension fund assets. To get a more accurate picture, it is necessary to include shares held by pooled funds in which pension funds invest. The Financial Survey of Pension Funds found that UK workplace pension schemes had £540bn invested in pooled equity vehicles as of December 2019, on top of the £178bn of shares directly owned, giving a total global equity holding of £718bn.14 The survey doesn’t provide a breakdown between global and domestic equities, but The Thinking Ahead Institute’s Global Pensions Asset Study estimates that UK pension funds had just 31 per cent of their equity investments concentrated in domestic equity in 2020.15 This suggests pension funds were holding approximately £223bn of UK equities. As the total market capitalisation of UK-listed public companies was £3.93trn16 at this time, this means pension funds held less than 6 per cent of the market.

This weakening link between corporate Britain and pension savers has been driven by de-risking, as defined benefit (DB) schemes have matured and shifted from equities to bonds; and diversification, as schemes have invested in a wider range of assets and geographies. Data from ONS examining investment by pension funds, insurance companies and trusts from 2000-2017 shows that the increase in UK pension funds’ investments in overseas equities (including both listed and unlisted equities) over the period accounted for 21% of the decline in value of their investments in domestic equities.17

As recently as the 1990s, it was common for DB schemes, which then represented the vast majority of workplace pensions and still account for more than half of UK pension wealth,18 to allocate up to 60 per cent of their investments to UK equities. But as these schemes closed to new members and then to future accrual, schemes shifted their investments from higher returning but generally more volatile equities into bonds. Between 2006 and 2020, allocations to equities almost halved, falling from 52.6 percent to 27.8 per cent. At the same time, increasing geographical diversification meant the percentage of equities held that are UK-listed has declined from 48 per cent to 13.3 per cent.19 The result is that over the period allocations to UK-listed shares among DB schemes declined from 25.3 per cent to 3.6 per cent.

Over this same period defined contribution (DC) schemes have emerged as the most common form of pension in the private sector, with almost 10 million UK workers actively contributing. As these arrangements are typically newer, members have had less time to accumulate assets in them, but they still have £470bn in assets – approximately 1/8 of the UK’s pension wealth – and are growing rapidly. The fact that members of these schemes are on average younger means that the schemes have higher equity allocations, as these members can tolerate greater volatility in return for higher long-term returns. However, UK equities typically only make up a quarter of their assets, with significantly more being allocated to global equities.20

The decline of UK shares held by UK pension funds also reflects the continuing direction of government and regulatory policy for pension funds. Successive governments have encouraged pension funds to diversify away from equities and into other asset classes, notably private equity, venture capital and infrastructure. Most recently, in summer 2021, the Prime Minister and Chancellor wrote to UK pension schemes to urge them to fund privately financed infrastructure projects,21 while in November 2021 the Department for Work and Pensions opened a review of the charge cap on DC default funds to allow them to invest more in private equity.22 Whether these interventions aimed to support pension beneficiaries or the wider UK economy is debatable. In addition, the funding regulations for defined benefit pension schemes mean that short-term volatility of funding can be highly damaging, leading to requirements for additional contributions, reduction of benefits, or even scheme closure – despite the fact that pension funds are, by definition, investing for the longterm. In combination, these factors have encouraged UK pension funds, especially defined benefit pension schemes, to reduce their investments in UK equities.

So, it is clear that while using different sources and definitions of pension fund investment may give slightly different figures for the proportion of shares in UK-listed companies owned by pension funds, they all tell the same story of a significant decline in investments. As DB scheme memberships have aged, they have moved investments from equities to bonds. In addition, the DC schemes that have largely replaced them as vehicles for accumulating pension wealth invest in a more diversified set of growth assets. The result of these changes in asset allocation is that UK pension funds now own less than 6 per cent of listed UK equities.

Pension wealth inequality

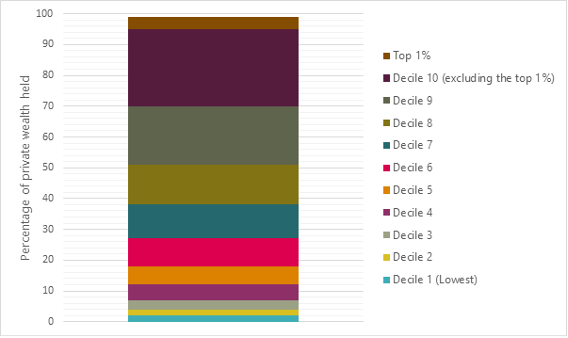

Even the returns to shareholders that do accrue to pension savers disproportionately benefit a wealthy minority. This is because the distribution of private pension wealth23 in the UK is highly unequal, with a Gini coefficient of 72 per cent - more than double the UK’s income inequality Gini of 34.6 per cent.24 The richest 20% of UK households by income own 49% of pension wealth in the UK - almost as much as the poorest 80% combined.

Figure 3: Household pension wealth by income decile 25

- 14 ONS, Financial Survey of Pension Schemes 2019 results, 2020

- 15 Thinking Ahead Institute, Global Pensions Asset Study 2021, 2021

- 16 Statista Market value of companies listed on London Stock Exchange 2015-2021, Published by Statista Research Department, Dec 13, 2021 https://www.statista.com/statistics/324578/market-value-of-companies-on…

- 17 Office for National Statistics, Investment by insurance companies, pension funds and trusts (MQ5) (Table 4.2), 2019

- 18 The Investment Association, Investment Management in the UK 2020-2021 https://www.theia.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/IMS%20report%202021.p…

- 19 Pension Protection Fund, The Purple Book 2020 https://www.ppf.co.uk/sites/default/files/2020-12/PPF_Purple_Book_20.pdf

- 20 0 Schroders, FTSE Default DC Schemes Report, May 2016 https://www.schroders.com/en/sysglobalassets/schroders/pdfs/w48918-ftse…

- 21 Igniting an investment big bang: a challenge from the prime minister and chancellor to the UK’s institutional investors https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo… file/1008814/A_Challenge_Letter_from_the_Prime_Minister_and_Chancellor_to_institution__1_.pdf

- 22 DWP consultation, Enabling investment in productive finance, November 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/enabling-investment-in-prod…

- 23 Private pension wealth is defined as “The value of any pension pots already accrued that are not state basic retirement or state earning related. This includes occupational pensions, personal pensions, retained rights in previous pensions and pensions in payment.”

- 24 Office for National Statistics, Total wealth in Great Britain: April 2016 to March 2018, 2019

- 25 Office for National Statistics, Pension wealth in Great Britain: April 2016 to March 2018, 2019, table 6.13

The introduction of auto-enrolment has brought more low-paid people into the occupational pension system and will, over time, increase the level of private pension wealth in the lower deciles. The percentage of UK employees contributing to a workplace pension has increased from 47 per cent in 2012 to 78 percent in 2020, with the largest increases in participation coming among the lower pay brackets.26

But participation is still strongly correlated to income, with just 41 per cent of full-time private sector employees with a gross weekly income of £100 to £199 belonging to a pension scheme. Lower earners and those brought into workplace pensions by auto-enrolment are also more likely to belong to DC schemes27 with low contribution rates,28 meaning they will build up their private pension wealth at a slow rate.

This suggests that even the minority of returns to shareholders that do accrue to pension funds disproportionately benefit a small number of households with high levels of pension wealth.

The argument that dividend payments ‘pay our pensions’ is therefore doubly misleading – pensions only account for a small proportion of the recipients of dividend payments and buybacks, and even within that small proportion, most of the benefits accrue to the wealthiest households.

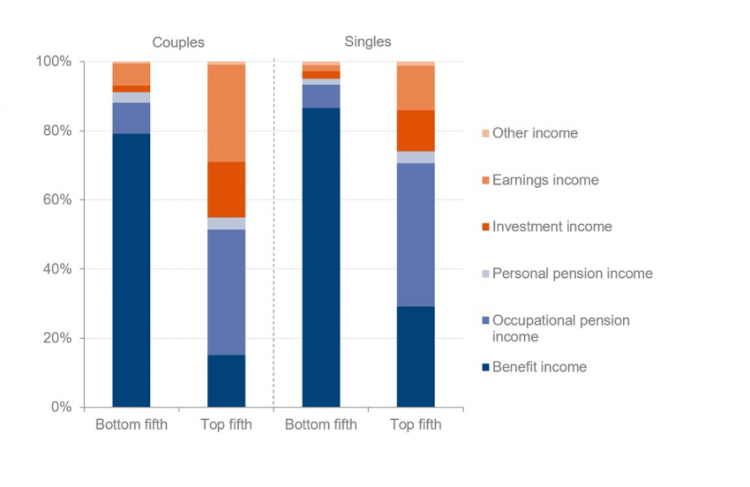

It is worth noting that the poorest pensioners depend largely on the state pension, rather than private (personal or occupational) pension savings, for their income in retirement. Their interests are therefore best protected by policies to protect the level and access to the state pension. Current government policies to raise the state pension age to 68 are particularly damaging for the poorest pensioners, who have significantly lower healthy life expectancy than their wealthier peers and at the same time have far less, if any, alternative sources of income to support their retirement. For many pensioners, and in particular the poorest, corporation tax is more important than dividends in terms of the contribution of corporate Britain to their pensions.

Figure 4: Sources of pensioners' income by income distribution 29

- 26 ONS, Employee workplace pensions in the UK: 2020 provisional and 2019 final results, published 10 May 2021 https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/workplace… ns/annualsurveyofhoursandearningspensiontables/2020provisionaland2019finalresults?_sm_au_ =iVVp8brjj79MnLQnW2MN0K7K1WVjq

- 27 Ibid

- 28 DWP, Workplace pension participation and savings trends of eligible employees: 2009 to 2020 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/workplace-pension-participatio…

- 29 Office for National Statistics Pensioners’ Incomes Series: financial year 2019 to 2020 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/pensioners-incomes-series-fina…

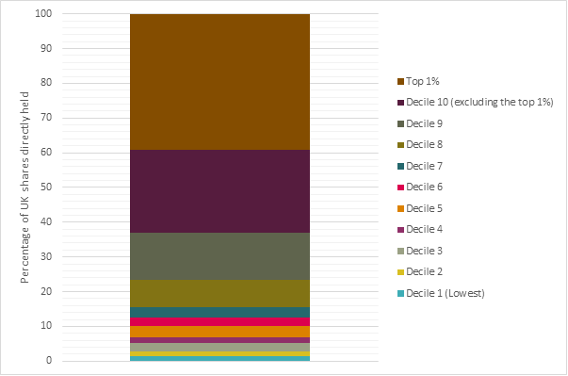

Individual direct share ownership

Private share ownership (ie that owned by individuals directly rather than through a pension fund) in the UK is even more unequally held than pension wealth. The richest 1 per cent of households own 39 per cent of total share-based wealth, more than the poorest 90 per cent combined. Importantly, unlike pension wealth, which is deferred labour income, private share wealth can be liquidated in the here and now, and consumed at the asset owner’s discretion.

Figure 5: Proportion of total share ownership by household income 30

- 30 Office for National Statistics, UK shares and private pension wealth by household income: Great Britain, July 2010 to June 2016 and April 2014 to March 2018, 2021

The figures for private share ownership imply that this only accounts for a small proportion of the ownership of corporate Britain – though it does highlight how those in the upper income deciles have a considerable stake in the fortunes of large companies, while for those on lower incomes this is negligible.

These figures suggest that only a negligible proportion of dividend payments and share buybacks accrue to the workers who create the revenues from which those dividends and buybacks are funded. However, there is one class of employee that does enjoy significant shareholdings in their employers. Research by Common Wealth found that as of May 2020, just over 700 executives at 86 of the largest non-financial UK companies held a collective £6bn in equity at their respective corporations, representing nearly £8.5 million per director.31

This contrasts with median share-based wealth of around £2,800 for a household in the fifth decile of the UK income distribution – a wealth ratio of approximately 3,035:1. 32

The cost of financial intermediation

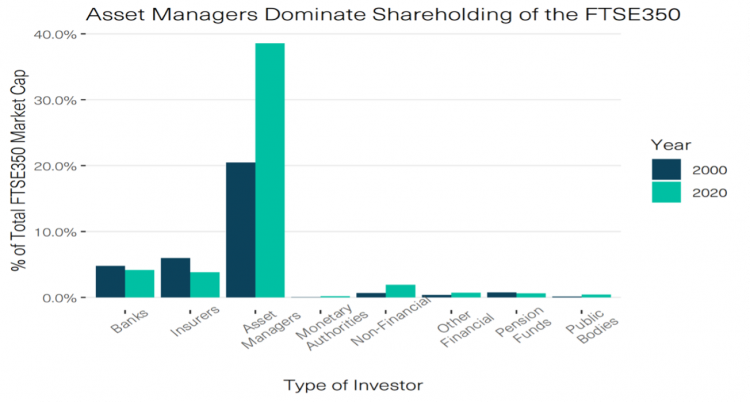

In addition to thinking about ‘who benefits’ from returns to shareholders, it is useful to consider who controls those shareholdings, as well as who owns them. Most shareholdings are managed by professional asset managers, who make investment decisions on behalf of the ultimate provider of capital and beneficiary, such as a pension fund or an individual saver.

Figure 6: Types of firms holding shares in the FTSE 350 33

- 31 Commonwealth, Commoning the Company, 2020

- 32 ONS, UK shares and private pension wealth by household income: Great Britain, July 2010 to June 2016 and April 2014 to March 2018

- 33 Adrienne Buller and Benjamin Braun (2021) 'Under new management: Share ownership and the growth of UK asset manager capitalism', Common Wealth

As Common Wealth have argued, the rise of the asset management industry is the product of two related trends in ownership without historical precedent: the combination of significant reconcentration of ownership within a small top cohort of minority shareholders, and the universal nature of these shareholders, meaning their ownership of assets is distributed across all geographies and industries. In contrast to the image of the activist shareholder, on which the prevailing ‘shareholder primacy’ regime of corporate governance is based, asset manager capitalism is defined by a structure of ownership in which the dominant owners of a corporation are motivated not by the performance of individual portfolio companies, but by the accumulation of further assets under management. In other words, asset managers pursue a fee-based business in which what matters is the total size of assets under management, rather than necessarily the specific performance of assets owned. 34

A study by the Financial Conduct Authority estimated that typical annual fees charged by an ‘actively managed’ investment fund represent 0.9% of assets under management (a significant amount of money for funds worth tens or hundreds of millions of pounds), but fees can vary depending on the type of asset or investment. 35 The FCA study also noted that typical profit margins in the industry are 36%, even before one includes the profit-sharing element of staff remuneration.

Pay in the asset management industry is high. Across the FTSE 350 firms in the “investment banking and brokerage” sector including asset managers, average pay for an employee at the 75th per centile of their companies pay distribution stood at £140,000 in 2020.36

Bearing in mind that a quarter of employees at each company earn *more* than the employee at the 75th per centile, this amounts to thousands of people earning hundreds of thousands of pounds across the industry. These costs are ultimately borne by the industry’s clients, paid for in part by the returns on their investments. Therefore, this is another important aspect of ‘who benefits’ from returns to shareholders – these returns help to fund extraordinarily large pay awards for wealthy workers in the financial services industry.

High salaries in the asset management industry are not the only way in which value leaks out of the investment chain before it reaches the pension scheme member. The finance industry in general is notoriously inefficient, with studies by Thomas Philippon finding the industry had not shown any productivity improvements over the last 130 years.37 Although certain charges are capped for many DC members, an issue that effects pension schemes in particular is the sheer number of costs and charges that must be borne across a complex investment chain. A 2014 DWP consultation on pension fund charges identified a non-exhaustive list of 26 different types of costs or fees. This includes the cost of advice and professional services, administration and governance, banking and depository fees and transaction costs.38 So, even to the extent to which pension funds do hold UK shares, the high cost of financial intermediation means that this is not an efficient way of sharing the value created in UK businesses with workers.

Conclusions and recommendations

To examine ‘do dividends pay our pensions’ and analyse who does benefit from shareholdings in UK companies, this research has drawn on multiple government and industry sources. This highlights the difficulties associated with identifying the underlying providers of capital for and beneficiaries of investments in UK companies. Given the implications of a company’s ownership structure for the impact it has on society – eg does it serve to enrich ordinary savers or the already wealthy – this is a hindrance to effective policy-making in relation to the regulation of those companies.

Despite the challenges presented by the research, the findings inarguably demonstrate a minimal and diminishing link between the fortunes of the UK’s biggest companies and the pensions of working people. UK pension funds account for a small and declining proportion of shareholdings. Individual investments are overwhelmingly concentrated amongst the very rich. Wealthy asset managers use their control of shareholdings to accumulate vast pay awards from the investment process.

At the same time, corporate leaders are under significant pressure to deliver ever greater returns to shareholders. High Pay Centre analysis suggests that 82% of FTSE 100 CEOs performance-related pay is linked to financial metrics relating to profitability, dividend payments, buybacks and share price gains.39 Dividend payments and share price movements are the subject of frenzied analysis and speculation from investors and commentators.

The identity of the share owners stewarding corporate behaviour against this backdrop is critically important. When a much greater proportion of company share ownership was concentrated amongst UK pension funds that could be expected to take a longterm perspective on their investments, and represent UK pension savers who have to live with the social and environmental consequences of prevailing business practices, we could have greater confidence in the capacity of investor stewardship as a safeguard against short-termism and exploitative or unsustainable practices. Higher pension fund share ownership at least meant that a more substantial element of returns to shareholders benefited ordinary pension savers (albeit to an unequal degree as a result of pensions inequality).

This is increasingly not the case. The argument that we need to divert some of the wealth currently used to fund returns to shareholders to the workers that create it is overwhelming. Wage growth has trailed behind increases in profitability and returns to shareholders. This must change so that working people benefit fairly from the success of the companies they work for – and claim a fair share of the value they create.

To this end, we recommend reform of the UK’s corporate governance system to remove the priority given to shareholder interests, promote worker directors on company boards and encourage a focus on sustainable, long-term growth in the interests of all stakeholders. This will involve changes to company law and governance practices, alongside policies to promote collective bargaining.

Recommendations for reform

Directors' duties

At the moment, company directors are required by law to prioritise the interests of shareholders over those of other stakeholders. Alongside existing legal duties, there are strong cultural norms and financial incentives, as set out above, that encourage directors to focus on maximising the wealth of shareholders as their priority.

The requirement to prioritise the interests of shareholders does not, as has been shown above, protect our pensions. And, as has also been shown, excessive dividend payments leave companies more vulnerable to economic shocks and contribute to the UK’s long-term problem of underinvestment.

There is strong public support for the legal duties of company directors to change, with 76% of workers agreeing with the following statement, compared with 5% who disagreed:

“When making decisions, businesses should be legally obliged to give as much weight to the interests of their staff and other stakeholders (eg local communities) as they give to the interests of their owners or shareholders”.40

Given the benefits to the workforce, other stakeholders, the company itself and wider society, it is time the law caught up with the public. Reform should rewire companies for long-term success. To that end:

- Directors’ duties should be rewritten to remove the current requirement for directors to prioritise the interests of shareholders. Directors should be required to promote the long-term success of the company as their primary aim, taking account of the interests of stakeholders including the workforce, shareholders, suppliers, customers and the local community and impacts on human rights and the environment.

A possible formulation, based on the existing wording with some revisions, is set out below:

“A director of a company must act in the way s/he considers, in good faith, would be most likely to promote the long-term success of the company, and in so doing, should have regard to the need to:

i. deliver fair and sustainable returns to investors

ii. promote the interests of the company’s workforce

iii. foster the company’s relationships with suppliers, customers, local communities and others, and

iv. take a responsible approach to the impact of the company’s operations on human rights and on the environment...”

Worker directors on company boards

Reform of board composition is also important to change the culture and priorities of the boardroom. Given the strong interdependence of the workforce with the company they work for, we believe that worker directors should be included on company boards. No company can succeed without the skills and commitment of its workforce; and at the same time, decisions made by the company have a major impact on the lives of the people who work there. Worker directors would bring people with a very different range of backgrounds and skills into boardrooms, helping to challenge ‘groupthink’, and improving the quality of board decision-making. While the 2018 Corporate Governance Code requires listed companies to put in place measures for boardroom engagement with the workforce, most companies have simply designated a non-executive director for this role, with only a handful of companies allowing workers to speak for themselves as company directors on the board.

- Worker directors, elected by the workforce, should comprise one third of the board at all companies with 250 or more staff.

Reporting by companies and the investment industry

Our research has demonstrated that the argument commonly used to justify the share of company profits paid out to shareholders and the privileged place of shareholders in corporate governance is flawed. However, as this paper has shown, it is not straightforward to find out who are the ultimate beneficiaries of shareholder returns. We need clearer data from the investment industry on who are the providers of the capital that they invest. To ensure the appropriate levels of disclosure, this should be an obligation for the industry as a whole. While transparency alone is clearly not enough, it is an important step towards rebalancing power within the company.

We also need clearer reporting from companies to show how they are distributing their revenues and profits among different stakeholders and how this is balanced with investment for the future in R&D and training.

- We recommend that companies should be required to report on their spending on wages, R&D, training, dividends, share buybacks and executive pay over a 20 rolling ten year period so that all stakeholders can see how these amounts have changed over time.

- In addition, companies should report on the average annual percentage pay rise (or otherwise) per worker tracked against the annual percentage rise in total shareholder returns over a rolling ten year period.

Distribution of rewards

Reform is needed to enable workers at UK companies to access a bigger and fairer share of the wealth they create.

Collective bargaining is the best way of raising pay sustainably – and it brings many other benefits too. Research, controlling for differences in workplace and worker characteristics to isolate the impact of collective bargaining, shows that as well as raising pay, workplaces with collective bargaining have more training days, more equal opportunities practices, better holiday and sick pay provision, more family-friendly measures, less long-hours working and better health and safety. 41

Employers and companies also benefit. Collective bargaining is linked to lower staff turnover, higher innovation, reduced staff anxiety relating to the management of change and a greater likelihood of high-performance working practices.

A range of factors, including industrial changes and anti-union legislation, have led to a reduction in the share of the workforce covered by collective bargaining agreements, especially in the private sector. However, over the last few years – starting before and continuing through the pandemic – union membership has started to rise, both in absolute numbers and as a proportion of the workforce, including in the private sector.

But there are still too many barriers to workers coming together in unions to negotiate collectively with their employer, and we recommend the following measures to address these barriers:

- Unions should have access to workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership and collective bargaining (following the system in place in New Zealand);

- New rights to make it easier for working people to negotiate collectively with their employer;

- The establishment of new bodies for unions and employers to negotiate across sectors, starting with hospitality and social care.

Direct profit-sharing mechanisms can also play a useful role in enabling workers to benefit directly from company success. To ensure that schemes are inclusive and benefit low paid workers and those on insecure contracts, schemes should be open to all staff regardless of contract type or hours worked.

- 34 Ibid

- 35 Financial Conduct Authority, Asset Management Market Study Interim Report, 2016

- 36 Figures based on High Pay Centre analysis of annual reports

- 37 Thomas Philippon, Finance, Productivity, and Distribution, Global Economy and Development at Brookings, October 2016

- 38 DWP, Better workplace pensions: Further measure for savers, March 2014 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uplo… file/298436/better-workplace-pensions-march-2014.pdf

- 39 High Pay Centre, CEO pay and the workforce: how employee matters impact performancerelated pay in the FTSE 100, 2020

- 40 BritainThinks polled 2,134 adult workers in England and Wales. The poll was conducted between 13th – 21st May 2021. Results were weighted to be nationally representative according to the ONS Labour Force Survey Data. 76% agreed (and 5% disagreed) with the following statement: “When making decisions, businesses should be legally obliged to give as much weight to the interests of their staff and other stakeholders as they give to the interests of their owners or shareholders.”

- 41 Professor Alex Bryson (UCL) and John Forth (NIESR), The added value of trade unions New analyses for the TUC of the Workplace Employment Relations Surveys 2004 and 2011, TUC 2017 and Professor Alex Bryson (UCL) and John Forth (NIESR), Work/life balance and trade unions Evidence from the Workplace Employment Relations Survey 2011, TUC 2017. For synthesis of findings and further sources please see TUC (2019) A stronger voice for workers – how collective bargaining can deliver a better deal at work https://www.tuc.org.uk/researchanalysis/reports/stronger-voice-workers

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox