Challenging Amazon Report

Amazon is a global giant, worth an estimated $1 trillion (£810 billion), directly employing over 850,000 workers globally, and shipping to over 100 countries.[1] It has expanded its portfolio into tech development by establishing Amazon Robotics, data through Amazon Web Services, and procurement through Amazon Business (similar to Amazon retail but for businesses and other organisations including local government and education institutions). It has become much more than the ‘Everything Store’ recognisable to so many.

Amazon is also known for the multiple ways in which its business model abuses workers’ rights, is actively anti-union, minimises its tax contributions and leverages its position to stifle competition and dodge scrutiny.

During the Coronavirus pandemic Amazon has seen its market value rocket, registering US $75 billion dollars (£58 billion) in revenue for the first quarter (equivalent to £25 million an hour).[2] Amazon’s second quarter performance showed no signs of slowing down, generating $88.9 billion (£68 billion) – up 40 per cent on Q2 2019 – and doubling their net profit to $5.2 billion (almost £4 billion) versus a year ago.[3] In just one day during the pandemic, Jeff Bezos increased his fortune by US $13 billion (approximately £10 billion), keeping him well on track to become the world’s first trillionaire by 2026.[4]

But while their profits surged, so did reports of the unsafe working conditions in their fulfilment centres across the globe. In the US, in Spain, in France, in Italy, in Poland, in Germany and in the UK, workers raised the alarm and unions demanded they do better, organising strikes to try and bring Amazon to the table when they dragged their feet or refused to introduce essential safety measures to reduce the risk to these key workers.

Several workers in the US who raised the alarm did so at great personal cost, resulting in their sacking. As Tim Bray, a senior Vice President at Amazon who resigned over the companies handling of the Covid-19 crisis and the firing of the workers involved said in an open blog regarding his decision:

“The justifications were laughable; it was clear to any reasonable observer that they were turfed for whistleblowing.”[5]

But for unions who have been campaigning for Amazon to recognise them and do better for their workers for some time, this behaviour is nothing new.

We believe Amazon must be challenged so that it does not become so powerful that its efforts to trample on workers’ rights are seen as simply a fact of life that cannot be confronted.

This report sets out the ways in which Amazon’s business model is extractive, exploitative and unfair, and the ways in which this can be challenged.

First, through a literature review we highlight the global abuses of workers’ rights and safety; the multiple ways Amazon games the system through tax minimisation and public subsidies; how it leverages its position in the market to dominate and stifle competition; its use of intrusive data gathering and surveillance technology; and the environmental impact of its business model. All of which combine to strengthen its position and dominance. We also demonstrate how public bodies and unions here and internationally have sought to challenge them.

Using Freedom of Information requests and research provided by Tussell Ltd and commissioned jointly with GMB, we then explore if and how UK local authorities have been able to engage with Amazon as an employer. We also examine the extent to which Amazon is benefitting from public money through the procurement of goods in the marketplace and contract awards for its Amazon Web Services (AWS). Given the commitments to decent work and social value in procurement and commissioning in public policy over recent years, we believe government should be wary of propping up Amazon’s business model with public money when we know it does so much to downgrade workers’ rights.

Challenging Amazon’s ability to downgrade workers’ rights requires three things:

i) Strong trade unions

ii) Local and national governments prepared to stand up to companies that abuse workers’ rights; and

iii) New global rules that set a higher floor for the treatment of workers and ensure that no company is too powerful to break it.

We urge Amazon to recognise and engage with unions as the best way to ensure workers’ rights are protected. But if Amazon will not do better for its workers, then unions and governments at all levels must work together to make sure that they do.

Amazon’s growing presence in the UK

Here in the UK, Amazon continues to increase its presence. In 2019 its UK sales revenue increased by 23 per cent to £13.4 billion (outpacing global sales revenue growth of 20 per cent). As sales increase so does Amazon’s growing network of distribution centres and number of employees which stands at 21 distribution centres, 3 Development Centres, over 30,000 direct employees, as well as multiple Amazon delivery stations and indirect employment through their supply chains, which Amazon themselves estimate to have created 122,000 additional jobs in 2018[1]. They have also recently announced the creation of 7000 new jobs, nearly half of which will come from three new distribution sites across the UK[2].

Reports also suggest Amazon will expand its presence in the UK through the launch of ‘Amazon Go’ convenience stores – where Amazon technology is used to create a checkout-less experience for customers. Ten sites are reportedly planned with a further 20 potentially opening down the line[3]. As is the case globally, their presence in the UK through the cloud computing arm of their business, Amazon Web Services (AWS) is also growing. Amazon Web Services UK turnover hit £850 million in 2018, doubling its market footprint[4]. A substantial part of AWS growth is in the private sector, particularly in banking[5], where concerns have been raised about the increasing concentration of cloud services into the hands of the big three (AWS, Google and Microsoft), including by the Treasury Select Committee[6].

However, equally concerning (and particularly given the Treasury Select Committees concerns) is their increasing presence in the public cloud, where Amazon Web Services now account for over a third of the services that store government held information and are one of the main providers of Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) and Platforms as a Service (Paas)[7].

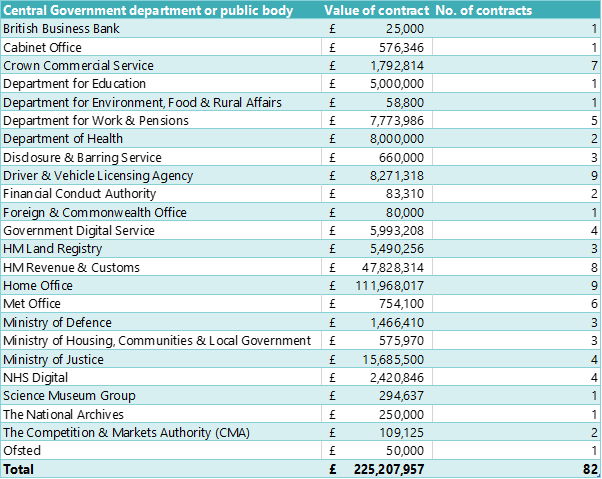

Joint research commissioned by the TUC and GMB shows the extent to which Amazon is benefitting from public contracts. HMRC, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), the Cabinet Office, the Drivers, Vehicles and Licensing Agency (DVLA), NHS digital, and the National Crime Agency have all awarded contracts in recent years to Amazon Web Services with a lifetime value of over £225 million as the table below sets out.

In 2020 alone, Amazon has been awarded contracts with a lifetime value of over £23 million, including contracts related to testing and tracing valued at £8.3 million[1]. While local government thus far has spent less on Amazon Web Services, they do spend through the Amazon Marketplace. Amazon have also been named on a procurement contract with a potential lifetime value of up to £400 million to create a centralised digital marketplace for the Yorkshire Purchasing Organisation (YPO) – a procurement organisation publicly owned by 13 local authorities.

Amazon’s growth seems set to continue. Against the backdrop of the coronavirus and the changing nature of retail particularly, warehouse and logistic based jobs are increasing, as demonstrated by the recent announcement from Amazon that they will create new jobs in the UK to meet increased demand[2].

Both central and local government should be holding Amazon to account, ensuring their business model doesn’t hurt workers and communities. But at present, instead of demanding Amazon do better, government in the UK is failing to challenge their numerous damaging business practices, either because they lack the tools to do so or the willingness to act.

All the while as we set out in the rest of the report, Amazon continues to operate a business model that functions on driving down workers’ rights while benefitting from the public purse through the millions of pounds spent on data services and the procurement of goods, as well as the enabling infrastructure that government provides.

Criticisms of Amazon

As trade unions, our focus is improving the rights of those who work at Amazon. But while tackling every aspect of Amazon’s business model is beyond the scope of this report, it is important to set out the many criticisms levelled at the company to understand the complexities of their activities and the challenge this poses in pushing for more accountability from the global giant.

Working for Amazon

Much of the controversy around Amazon’s employment practices focus on their fulfilment centres and distribution networks. The company drive to ‘put the customer first’ has pushed employees to extremes and many have spoken out about a range of issues, some of which are presented below.

Fulfilment centres and offices

Reports of long, gruelling shifts with unreasonable productivity targets and unfair shift patterns are common in Amazon fulfilment centres. In the UK, pickers are expected to pick and pack around 300 items per hour, employees tend to only either do day or night shifts and working weeks average around 55 hours/ 10-hour days, especially over the peak Christmas period[1] Staff were reported to have slept in tents near the Dunfermline site in Scotland to save money and so they are not late for work, which would risk them being penalised or fired[1].

I have the shoulder pain for a few months. I had physio but didn't help too much. I damaged my back and right shoulder muscles doing stow by trying to hit the rates around 280 items/hour. The same movements (repetitive) make the pain very bad.

Workers’ productivity performance is also monitored, and they are harassed and disciplined or even sacked if they dip below targets. One undercover reporter said that while working in an Amazon fulfilment centre in Essex over the black Friday period, scores of staff who dipped below targets were sacked. It has been reported that the high level of monitoring creates a culture of fear, many workers do not take their legally entitled breaks because of the impact it has on productivity and the subsequent risk to hours and ultimately employment, particularly for the many temporary and agency workers it hires. The scale of the warehouses is so vast that many employees do not have time to go to the break room or for bathroom breaks – one report stated that employees were urinating into bottles[1].

I am pregnant and made to stand and work for 10hrs without a chair, they constantly mention my idle time and they are telling me to work hard even though they know I am pregnant. I am feeling depressed when at work.

The gruelling working conditions have led to serious accidents at work and staff collapsing from exhaustion. In just over three years, ambulances were called out 600 times to 14 Amazon warehouses in Britain[1]. In more than half of those cases patients were taken to hospital. Over the three years, the highest number of calls (115) came from Amazon’s Rugeley site; in comparison, a similar sized supermarket distribution centre a few miles away had only 8 calls over the same period[2]. GMB surveyed its members who worked for Amazon, revealing that 87 per cent said they were in constant or occasional pain due to their workloads[3]. In the US there have been reports of calls to 911 for staff attempting suicide or having suicidal thoughts[4] and people have died while at work[5] .

dehumanising you are a number not a person if you have health and safety issues the Amazon way is to pay you off and replace you with temporary workers with less terms and conditions

Other examples of unacceptable working conditions, which were revealed by GMB through Freedom of Information requests, included workers being forced to work in freezing temperatures, and a dangerous near-miss heavy machinery incident caused by a ‘lapse of concentration possibly due to long working hours.’ A number of workers who made health and safety complaints to regulators did so anonymously, because they said they feared being sacked by Amazon.[1]

GMB have provided us with case studies (see box 1) and testimonies from Amazon workers, highlighting some of the awful experiences and conditions workers are subjected to, including the mistreatment of pregnant women and harassment, verbal and physical abuse of workers from other colleagues.

Some reports from the corporate offices suggest the culture is just as demanding. Workers are encouraged to tear each other apart in meetings, work long and late hours and never disconnect. Staff have been seen ‘weeping’ at their desks and even junior level employees must sign lengthy confidentiality agreements[2] .

Box 1: Case studies of unfair treatment at Amazon.Case study one: In the summer 2019 Amazon called a Team Leader at their Doncaster Amazon site to attend a disciplinary hearing. She was 38 weeks pregnant. The charges were for gross misconduct. Her crime that caused the downtime during work, was due to pregnancy related illness. She was made to attend a five-hour disciplinary hearing, she was not offered food or a drink. To Amazon’s surprise the member concerned was represented by a GMB Official, who managed stop Amazon from dismissing her. She was given a final written warning. The member then appealed. Amazon then set up the appeal to take place on her due date, Amazon also wanted her punishment to commence after her maternity leave. The woman worked for Amazon for 8 years, had an unblemished record and had progressed to be a team leader. Case study two: A female associate was working at an Amazon site. She was carrying out her morning duties, when at around 9am she noticed another associate staring at her. She tried to ignore him but noticed that he asked another associate if she was Romanian. He then came over to her, she realized he must have been on the premises drunk as the smell of alcohol was obvious. He tried to touch her and when she stepped back and asked for his login (name on his ID) he became aggressive and started shouting anti-migrant and misogynistic things at her and pushed her. “I got very scared and didn’t what to do because no one was around except one associate who was more scared then I was. He continued to push me and trying to hit me until an associate who saw that I’m in trouble came and told me to go away and ask for help from managers or security.” Managers eventually turned up and took the drunk associate to security. Shaken up, the associate who had been attacked was taken to the canteen where she was told it was not that big a deal and there was no need to record it as an incident. Twenty minutes later two other managers came to speak to her and record the incident but were equally dismissive saying that with 3000 people on site it was not possible for security to control everyone and see if they are drunk etc. The associate asked to go home as she was badly shaken, but management were more concerned with marking her absent for clocking off early than with what she had experienced. |

Last mile delivery drivers

Conditions for delivery drivers working on what is known as ‘the last mile’, who are usually required to be self-employed or are contracted through third parties, have also found the target driven nature of the business relentless, low paid and dangerous.

It is an awful place to work, can’t breathe or voice and opinion, feel like a trapped animal with lack of support and respect. Not human they treat you as if you are a robot

A 2016 undercover investigation revealed that drivers were expected to deliver up to 200 parcels per day. Drivers often worked more than 11 hours, breaking legal limits and by the time deductions for things like optional van hire, insurance etc. were accounted for, ended up earning less than the minimum wage at the time of £7.20 per hour[1].

By using self-employment and third party contracting, Amazon have been able to dodge any accountability for accidents, pushing all the risk and consequences onto drivers. This has been in the spotlight in the United States, where drivers delivering parcels for Amazon have been involved in fatal accidents. In one such case, the family of someone who was killed in an accident involving an Amazon delivery driver attempted to sue for wrongful death, they were told by the company’s lawyers: “The damages, if any, were caused, in whole or in part, by third parties not under the direction or control of Amazon.com” [2].

Probably the high target that has been set, because we have to work fast and work under pressure to make sure it is done, otherwise we are called upstairs (to see managers). Working at packing means I work a lot with my hands which is why I had a surgery.

However, it is well documented that Amazon drivers, though not directly employed by them, much like their warehouse colleagues, have their performance tracked and are under immense pressure to complete the routes they are given within certain time frames[1].

Many third-party contractors have become reliant on Amazon for business, but again Amazon has been known to terminate contracts at short notice, forcing businesses into bankruptcy. However, they are never liable. As one report puts it:

‘That means when things go wrong, as they often do under the intense pressure created by Amazon’s punishing targets — when workers are abused or underpaid, when overstretched delivery companies fall into bankruptcy, or when innocent people are killed or maimed by errant drivers — the system allows Amazon to wash its hands of any responsibility’[2].

Amazon, in response to criticisms of its employment practices, are keen to point out they abide by local labour laws and pay a competitive rate for distribution centre workers (£9.50 an hour in the UK for example). However, hourly rates are dependent on job roles, with pickers likely to earn an average £8.28 an hour[3] - just above minimum wage.

A look through reviews on recruitment websites reinforces what GMB have told us about what they are hearing on the ground from people working for Amazon and the gruelling conditions (see box 2)[4].

Historically Amazon have been known to have supressed unionisation and sack people who attempt to organise, encouraging managers to bust any unionisation attempts they may see[5]. They have even closed call centres in response to unionisation attempts in the US[6].

More recently they have come under fire for advertising an ‘Intelligence Analyst’ role which was specifically geared towards monitoring workers efforts to unionise and feeding back to senior management[7]. The advert was removed after Amazon was asked to comment on the article.

And it seems that this is not just a practice confined to their warehouses with a recent report emerging from the US of an Amazon Web Services employee warning colleagues that Amazon where monitoring employees with protected characteristics and any organising they may be doing. Amazon have denied the claims[8].

Box 2: Recruitment reviews about working for AmazonFulfilment Associate, Manchester Amazon preaches a lot of positivity and promises for the future but what you receive could not be further from the truth. The treatment is unfair and work life at Amazon is tough. People are favourite over others and hard work does not always get you far. You are watched all the time, going to the toilet for more than 5 mins feels like a crime although it takes 5mins or so to WALK to the toilet depending on where you are in the building. You are disciplined for being sick or falling ill. The work has a physical toll on you - and sometimes long-term effect on your physical health. Desperation is why some people continue working at Amazon despite the harsh treatment. Security Officer, Croydon I worked as a security officer for amazon in Croydon, it was not the best environment to work in, due to management at amazon are very rude and very unfair on the way they talk down to you, they also use people as a scape goats if anything thing goes wrong, be prepared for management to shout at you and belittle you. Multi-drop driver, Sheffield Sheffield amazon Logistics ltd they work u until u drop one of the many contractors who contract to amazon at Sheffield you have to do 20 plus drops an hour to deliver it’s like amazon have timed an athlete to deliver parcels so be prepared to take a bottle in van if you need the toilet and if you’re hungry you best get used to eating whilst driving. If you bring any parcels back to the depot you get a telling off they don’t hear any excuses even if you have a flat tyre you have to go back out and try again if you refuse you get the sack ! If you finish in 8 hours you have to phone the office someone will meet you to give you another hour’s parcels to deliver! In fact no need to ring office they will ring you as they know how many parcels you have left if you decide to park up for 20 minutes you get an annoying phone call to say get a move on your tracked and traced they know your every move and every parcel you have delivered whatever time you get asked to meet at the depot add 2 hours unpaid work you only get paid from moment you set off with a van load and drive out of depot which takes 2 hours sometimes longer as there is a bottleneck of all the vans waiting to load up a massive traffic jam then the re attempts are in your own time. One last thing if you don’t mind getting home at 8-9 every night including on a weekend and it’s a self-employed role no drivers are employed and even your driving is monitored by e mentor plus you’ll notice 15 people a day going for interviews this is because of the high turnover of staff. While amazon has an overall rating on websites such as Indeed of 3.6 out of 5, even the more positive reviews often cite the fast pace and stressful nature of working for Amazon. Warehouse worker, Trafford Amazon pays a lot of money to the workers but the work in amazon is very boring and challenging. But the pay is motivating. The working conditions are hard because u only get 2 30-minute breaks in a night shift and ur not allowed to sit down. Delivery Associate, Liverpool An easy job but is made awful by the long hours and your expected to work 6/7 days a week even though your self-employed your treated like your employed. Long hours, van rental is ridiculous price. |

There are many reports of poor employment practices at Amazon, from gruelling conditions to surveillance to poor management behaviour and they refuse to recognise or engage with unions unless forced. Amazon argue they would rather have direct dialogue with employees where there are problems, but recent evidence during the Covid-19 pandemic further suggests that they actively discourage organising in any form.

Amazon and the Coronavirus pandemic

When looking at Amazon’s social performance during the Covid-19 pandemic, versus its financial performance, the contrast could not be starker. While their share price rockets and market dominance spreads, the stories emerging from warehouse workers and drivers on the frontline has put a spotlight on the real human cost of Amazon’s business practices.

Done as a stop gap for finance. Run by idiots, a culture of informing on fellow workers, awful canteen, breakneck pace, no respect for anyone, useless rude managers. LONG shifts doing menial tasks with outdated broken equipment, fellow workers suffer the long hrs. If you need fast money this is the place, but you will be a zombie after a week, AVOID, if poss. Ripe with covid.

Reports of a lack of protective equipment or sanitary measures, no ability to social distance, unsafe, and unrealistic productivity targets still being in place have all emerged during the crisis[1]. As the number of Covid-19 cases in Amazon warehouses began to rise - Amazon workers across Europe[2] and America staged strikes and walk outs to try to get the company to act[3] and legal challenges have also been mounted by workers[4].

In France, following legal action from French unions, authorities ordered Amazon to temporarily sell and deliver essential items only to reduce the risk to workers while they investigated its health and safety measures. Amazon responded by closing their six warehouses for several weeks, eventually reopening after negotiating a deal with unions[5].

The German Union Verdi staged strikes at six Amazon sites across Germany after Amazon continued to stall on ongoing wage disputes and a push from the union to get a collective bargaining agreement for good and healthy work. Verdi stated “We are stepping up the pace because Amazon is not showing to this point any insight and is endangering the health of employees in favor of profit"[6].

Similarly, in Spain, CCOO union having had unsuccessful discussions with Amazon and limited improvements in safety measures, contacted the Labour Inspectorate to review Amazon’s response to the Covid-19 crisis. After much effort the action eventually led to over 100 safety measures being implemented in distribution sites across Spain[7].

Company more interested in speed than care for staff and client’s parcels. Long shifts with only half hour break. This isn't long enough as you have a face mask on for the full shift which is 8 or 10 hours. Also phoned in the night on day off. Some staff are bullies.

In the UK, GMB Union have exposed multiple examples of a lack of Covid-19 health and safety measures across their sites. A lack of social distancing, washrooms, sanitiser and poor cleaning regimes and no PPE have all been reported to GMB. There has also been video and photographic evidence of cramped conditions for workers when going through security, in corridors and in locker rooms. GMB exposed this publicly and stated their intention to go to the Health and Safety Executive and call for urgent inspections of all Amazon sites across the UK[1]. Within days, Amazon then began to implement several required Covid-19 safety measures.

Amazon state that they have implemented a range of safety measures and policies to tackle the spread of Covid-19 in their warehouses[2], but with Amazon revealing that nearly 20,000 of their workers across the US have contracted Covid-19[3], the evidence suggests they are doing the bare minimum unless forced[4].

The right to unlimited, unpaid leave was introduced at the start of the crisis, meaning many employees have had to make the choice between getting paid and their health if they needed to self-isolate. Worse still, despite the ongoing health crisis, since the start of May even that policy has been terminated, meaning many workers fear being fired if they miss a shift[5]. In California, where there is an entitlement to sick pay, there have been reports that Amazon told workers the law didn’t cover warehouses[6].

A temporary extra two dollars/pounds/euros ‘hazard pay’ on Amazon warehouse workers hourly rate ended in June despite the continued risk workers are taking and the sales boost Amazon is experiencing during the crisis.

And while Amazon says it likes to directly engage with employees, workers in America who were some of the first to speak up were fired for raising the alarm, prompting senior Vice President Tim Bray to resign stating in an open blog regarding his decision; “The justifications were laughable; it was clear to any reasonable observer that they were turfed for whistleblowing”[7].

Tax and subsidies

Another well-known criticism of Amazon is the low level of tax it appears to pay in its multiple markets. In fact, UK based organisation Fair Tax Stamp ranked Amazon the worst of the big six tech giants for aggressive global tax avoidance[1]. Looking at cash tax paid (as opposed to current tax charge or current tax expense) Amazon between 2010-2019 paid only US $3.4 billion (£2.7 billion) in tax on $960.5billion (£740 billion) of revenue and $26.8billion (£20 billion) of profits - significantly less than any of the other big six.[1]

Because of a complex business structure with lots of divisions it is hard to know how much tax Amazon is or isn’t paying (particularly outside of the United States) and Amazon does not reveal profits or corporation tax for its entire UK operation, which would include both its retail business and its logistics and warehouse division[3] .

What we do know is that Amazon Services ltd (the logistics arm) paid £14 million in UK corporation tax in 2018, which was a £10 million rise from the previous year of just £4.7 million. However total 2018 revenues for the whole UK operation were £14. 5 billion. Amazon have said they paid a total of £220 million in various taxes including corporation tax, national insurance, business rates and stamp duty and that business rates and employers NI accounted for over £120 million. That would suggest it paid less than £100 million in other direct taxes - experts have suggested they should be paying £100 million in corporation tax alone[4]. Outside of the UK, while there does appear to be some effort to recoup some of the tax lost to Amazon’s aggressive tax minimisation, they still appear to have multiple ways of gaming the system. For example, the EU ordered Amazon to pay 250 million euros (£222m) in back taxes to Luxembourg (where it runs many of its revenue streams through) in 2017[5]. However, between 2018 and 2019 they have received tax credits of nearly half a billion euros which will be deductible from any tax bill[6].

Receiving subsidies and tax deductions is commonplace in the United States, where they have also been known to threaten and pull out of warehouses and investment when demands for higher taxes are made[7] . The most high-profile example being Amazon’s withdrawal of plans to build a second headquarters in the Queens District of New York. The company was set to receive nearly US $3 billion (£2.4 billion) in subsidies in exchange for bringing 25,000 jobs to the area. Campaigners, including unions, objected to the subsidy and raised other concerns – and Amazon pulled the plug[8].

There have also been reports of similar activity in the UK. It is reported that between 2010 and 2015 the Scottish government gave Amazon £7.5 million in grants[9]. The Welsh government awarded Amazon a grant of over £7.7 million to support establishing operations in Neath Port Talbot where there is now a warehouse[10].

At local level, Amazon often benefits from local authority investment in infrastructure and site development, for example in Torbay where the council invested £15 million in a site linked to and eventually confirmed as being a new Amazon warehouse on the Exeter gateway[11]. In Darlington, the council has awarded a contract (with contributions from the site developer) to Arriva bus services to provide a service from the town centre direct to Amazon’s distribution centre, which will ensure the timetable suits workers shift patterns[12].

Earlier this year Amazon won a refund of £3.2 million on the rateable value of its warehouse premises in Rugeley. Dating back to 2011, the premises had been consistently valued at £3.18 million, but Amazon appealed this and managed to get the valuation reduced to £2.5 million[13] triggering the refund.

In response to criticisms over the decision, Amazon cited the role it has played in job creation and contributions to the economy across the UK, but while Amazon has brought jobs, councils have little power in rate setting (this sits with the Governments Valuation Office) and yet business rates are one of their only sources of income after years of cuts to their budgets.

There is also a longstanding issue of the disparity in rates between bricks and mortar retailers and online companies such as Amazon when it comes to rates for their premises. For example, in 2016-17 Tesco paid business rates of £700 million, while Amazon paid just £63.4 million despite generating far higher profits[14] (£8.7 billion versus Tesco operating profits of just over £1 billion)[15]. According to the figures obtained by the House of Commons Housing, Communities, and Local Government Committee, Amazon’s expenditure on business rates was 0.7 per cent of turnover, compared to 5 to 6 per cent for some of its more traditional competitors.[16]

Commenting on the Rugeley refund at the time, a representative of Cannock Chase Council pointed out:

‘Amazon describes itself as providing fulfilment centres supplying goods direct to the customer and clearly the business rates system does not reflect this, treating such sites as basic warehouses, which means that Amazon is paying substantially less than retail warehouses, and a fraction of the cost per square metre of high street shops’[17].

Amazon, with its huge leverage as a big employer can find ways to benefit from public money and investment here in the UK and elsewhere yet seems unwilling to pay its fair share in tax. It would also seem companies like Amazon have councils who want jobs and income brought into their area over a barrel - with little ability to influence the terms on which they do business.

Market power, unfair competition and lobbying

The complexity of Amazon’s business model as both a retailer and marketplace for other retailers, a logistics business and a tech giant and cloud service provider, means it can leverage its power in multiple markets and in multiple ways.

Its dominance as an online platform means small and medium businesses wishing to sell online have little choice but to engage with the platform if they want to reach consumers. For third party sellers this often means having to accept the raw end of a bad deal. Once part of the marketplace, third party sellers are often subject to bullying, high fees, and extensive data gathering on both their products and customers (which sellers themselves usually cannot access, while Amazon uses to its own benefit)[1].

These anti-competitive practices not only stifle competition but are likely leading to higher prices for customers. A recent report from the US estimates that Amazon keeps 30 per cent of each sale of a third-party seller on its site[2]. These fees are a combination of direct seller fees (usually around 15 per cent) and “optional” Fulfilment by Amazon (FBA) and advertising fees. Sellers are not obliged to take out the optional fees, but in not doing so their products are unlikely to be pushed on the website or feature in searches, meaning they are buried amongst the thousands of other products.

Similarly, third party sellers are not allowed to sell on any other platforms at a cheaper price (where maybe the fees are less, and the saving can be passed onto the customer). So almost certainly, rather than Amazon being the best on price, it is probably leading to higher prices for customers across the board. Somewhat ironically, the fees (worth USD $60 billion or £45 billion in revenue in 2019) are essentially a sales tax direct to Amazon which is then used to subsidise its other operations such as covering the costs of its logistics arm[3].

Looking to the US and the logistics market is useful as it potentially gives an indication of what may come if Amazon’s continued concentration of power and dominance is not challenged. Using its market power to coerce sellers into using its delivery operation has seen a rapid expansion of its share in the logistics market. In 2019 Amazon’s logistics operation delivered about one fifth of all e-commerce parcels, it has already overtaken the US Postal Service and is expected to overtake Fedex and UPS in terms of market share by 2022[4].

Amazon has also come under fire for its inability to regulate its marketplace and its Prime streaming service. Concerns have been raised about health and safety and counterfeits, with one investigation highlighting that over 4000 products on the US website had either been declared unsafe by federal agencies, ‘deceptively mislabelled’, or banned by regulators[5].

Here in the UK, MP David Lammy highlighted the use of racist language on a listing[6], Amazon did take the listing down once alerted to it, but it had been up for several months and shows the difficulty of regulating such a vast supply chain and range of products and sellers, as does the recent complaints regarding products on their website promoting hate speech towards people with Down’s syndrome[7]. Amazon have also been criticised for far-right programming appearing on their Prime streaming service and the availability of books written by known far right authors[8].

Given Amazon’s business model relies on the ability to minimise taxes, monetize the data it gathers and build monopoly power; it is unsurprising that they have stepped up their lobbying game where they can. In the US, Amazon have spent US$ 80 million (£62.5 million) over 10 years on lobbying[9] and between 2016 and 2018 the number of lobbyists they sent to Capitol Hill nearly doubled from 56 to 103[10].

It is not unusual for corporations to spend large sums of money lobbying in the United States, while this may not have a direct impact on the UK – when it comes to setting global policy agendas, it certainly does.

Amazon (along with other big tech lobbying) is having a direct impact on US lawmakers, threatening their efforts to pass digital protection laws and determine whether and how anti-trust law can and should be updated for a digital age. A recent joint report from the New Economics Foundation on behalf of the ITUC[11], outlines the influence big tech is having on shaping negotiations at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) regarding ecommerce and the digital chapters within free trade agreements, and the potential impact this could have on labour (see box 3)[12], arguing:

“Governments are promoting new rules that would further reduce their own authority to regulate in the interests of people, to the extent that they are behaving more as captives of corporations, including giant tech monopolies, than as guardians of the public interest”[13].

Box 3: Big tech and WTO negotiation on the digital chaptersHow Amazon and big tech are governed in the future will be impacted significantly by how the trade talks at the WTO on digital chapters in Free Trade Agreements proceed. Big tech is pushing for:

These proposals would favour large corporations who already dominate the digital infrastructure and have the scale to gather and use data. Campaigners and organisations such as the ITUC and Centre for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) are concerned these proposals go well beyond e-commerce and trade and could have significant impacts[1]. Below are just some of the concerns raised about the proposals:

|

Criticisms have also been levelled at the ‘revolving door’ between government departments and senior Amazon employees. In the UK in June of this year, it was announced that Doug Gurr, a top Amazon UK executive would be leaving his role at Amazon and taking on a temporary advisory role to the Cabinet Offices Government Digital Services team. This follows the 2018 appointment of the UK’s top tech advisor Liam Maxwell, who left his public office role to join Amazon Web Services as Director of Government Transformation. There have been similar reports of Amazon execs advising the current Trump administration having previously worked in government[1].

Amazon has also continued to increase its spending on advertising and marketing in order to promote itself and its influence as a brand and an employer, including TV advertising campaigns in the UK which include adverts about working in their distribution centres[2]. Globally, Amazon has increased its advertising expenditure significantly over the last decade and is now the biggest advertiser on the planet. Spending on advertising has increased from $0.6 billion (£0.45 billion) in 2009 to $11 billion (£8.4 billion) in 2019. Annual spending on advertising increased 34 per cent in 2019 alone[3].

Intrusive data gathering and surveillance technology

Fundamentally, Amazon’s business model is about data. Whether as a worker, seller or customer, the data we give to Amazon for free (even if you don’t end up buying something from their site, the search alone will create valuable data), allows them to aggregate the information gathered to create algorithms and model behaviours, trade and target data for advertising purposes and predict future trends – developing technology and directing products to us before we even know we need them.

US based citizen rights advocacy organisation Public Citizen found in a 2019 report that of Amazon, Netflix and Spotify, Amazon was the most intrusive in terms of data gathering and third-party tracking. Similarly, its privacy notices lack any sort of transparency, making it hard for consumers to know what they are opting into. While it is worse in the US, even with GDPR legislation in the EU, data privacy by default is still some way from being realised[4] and what the UK’s policy will be after the Brexit transition period comes to an end remains to be seen. Bearing in mind that government departments and local authorities are increasingly customers of Amazon, this is worrying both on an individual consumer level and for society more broadly.

As discussed, for those working at Amazon, surveillance is a common practice used by Amazon to keep track of its workers. Worryingly, and of great concern to unions, is that despite concerns already raised, surveillance of workers may well intensify with Amazon winning patents to develop tracking wristbands that workers would wear and would have the potential to monitor their every move, even vibrating when they are deemed to be doing something wrong[5]. They have also been trialling the use of this wristband technology under the guise of their Covid-19 response (the wristbands buzz when you get too close to a colleague)[6].

Unions and civil rights groups in the US have also raised the alarm about Amazon’s expansion into technology such as facial recognition. ‘ReKognition’ is already being used by US law enforcement agencies across the US and by the US Immigration and Custom Enforcement agency (ICE). Campaigners fear that unless regulated, it could be used to target immigrants, BAME communities and civil rights activists by authorities[7].

Environment

Amazon’s carbon footprint is similar to that of country the size of Denmark or Switzerland[1]. A combination of its delivery network and the huge amount of energy needed to support its growing infrastructure of data centres (its new data centre complex in Ireland is projected to use 4 per cent of the country’s entire electricity grid)[2] - means it is guzzling energy and emitting carbon at a rapid pace.

Amazon has been reluctant to disclose information on its climate performance, and the sharing of its footprint and announcement of its climate pledge emerged as a direct result of the organising and campaigning of the Amazon Employees for Climate Justice (AECJ). A group of mostly tech workers initially, they have lobbied the company to get them to be more transparent about their climate impact.

Yet, despite the company committing money to finding sustainable solutions, investing in 100,000 electric vehicles and pointing to it being on track to meet targets such as 100 per cent of its energy produced by solar, wind and other renewables by 2025 - Amazon saw its carbon footprint increase by 15 per cent in 2019, and this is before its Covid-19 related surge[3].

As it increases its warehouse and data centre presence across the globe, expanding its distribution network including into air cargo and airport expansion[4]; as well as continuing activities such as helping oil and gas companies to locate, extract and sell fossil fuels using its AI and cloud technology[5] - it is hard to reconcile Amazon’s pledges on climate and its actions.

The impact of undermining efforts to tackle the climate crisis will be felt by all of us, but as unions and the AECJ have highlighted, it is usually poorer countries and communities that are on the frontline of the climate emergency. In the US, the AECJ have argued that Amazon’s air pollution is having a direct impact on communities of colour, with 80 per cent of their non-corporate US operations located in areas with a higher percentage of people of colour than the metropolitan locations of its corporate offices[6].

While Amazon may argue that it brings jobs, investment and innovation, it has been shown time and time again to be downgrading workers’ rights, depriving governments of valuable tax revenues that could be used to support public services, stifling fair competition and damaging the environment. Amazon’s business model is extractive and exploitative, they must have their power checked and be challenged to do better.

Trade union activity

As discussed above we have seen many workers across Europe and America take action to force the company to do better in its response to the pandemic. But, while coronavirus has put the spotlight on Amazon, action to challenge its extractive and exploitative business model has been growing for some time.

This includes coordinated global action on ‘Prime Day’ – one of the most dangerous days for the company’s workers as they are pushed to meet relentless demand.[1] In the UK, the GMB’s ‘We are not Robots’ campaign highlighted the plight of Amazon workers.[2] Italy also made history when it secured the first ever direct agreement between unions and Amazon regarding shift patterns and fairer weekend working.[3]

It will be interesting to see how willing Amazon is to work with Swedish unions as the company prepares to make a big expansion in that market. Sweden has strong labour laws and high levels of union recognition. Over 70 per cent of Swedish workers are members of trade unions and 90 per cent of employees are covered by collective agreements. Amazon’s typically anti-union stance is not something that will be tolerated. In response to the news of its expansion into Sweden, Handels, the union for warehouse workers said: “Amazon is welcome in Sweden, but they have to sign a collective agreement”.[4]

2019 also saw the first global symposium bringing together unions, civil society organisations, tax and climate justice activists and digital privacy campaigners, to discuss Amazon’s power and how it might be tackled.[5] And before its Annual General Meeting (AGM) this year, unions and other stakeholders worked together to raise awareness of a variety of issues concerning Amazon’s practices with shareholders.[6]

Trade unions across Europe, including UK unions GMB, Usdaw and CWU have also recently called on the European Commission to open an investigation into Amazon’s “potentially illegal” surveillance of workers union activities. The letter, with 37 union signatories, states:

“Amazon’s plans to ramp up surveillance of workers across Europe and globally are yet another reminder that EU institutions should closely investigate Amazon’s business and workplace practices throughout the continent, as we suspect them to be in breach of European labour, data and privacy laws that our citizens expect to enjoy”[7].

In response 37 MEPs have written to Jeff Bezos demanding information about the company’s union and political monitoring activity, raising concerns about Amazon’s approach to what the company deems as “threat monitoring”.[8]

Tackling anti-competitive practices and governing the online infrastructure

The European Union has led the way on trying to curb Amazon’s anti-competitive, anti-trust practices. Having launched an investigation into whether Amazon was using sensitive third-party seller information to gain a competitive advantage in July 2019, reports from June 2020 suggest the EU will bring formal charges against the company.[9] This follows a previous anti-trust investigation opened in 2015 into Amazon e-books by the EU. This found that Amazon's e-books distribution agreements may be in breach EU anti-trust rules by requiring publishers to share information, and offer Amazon similar or better terms than those offered to competitions, or inform Amazon of more favourable terms given to their competitors.[10]

The Competition Commission of India has also launched an anti-competition investigation into Amazon (and others) over alleged violations of competition law and discounting (Amazon has launched a legal challenge to counter this).[11] And Jeff Bezos, along with the heads of Apple, Google and Facebook, has been brought in front of US Congress for questioning over anti-trust issues.[12]

In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has called on the government to introduce a new pro-competition regulatory regime that takes on big tech.[13] A Digital Market Taskforce has been established, bringing together the CMA, the Information Commissioner’s Officer (ICO) and telecoms regulator Ofcom to help design a new regulatory regime. The CMA has proposed that a Digital Market Unit be established within any new regime with the powers to enforce a code of conduct that stops platforms from abusing significant market power; introduce a ‘fairness by design duty’; and order the separation of platforms where necessary.[14]

The concentration of online infrastructure and cloud services into the hands of just a few providers, one of which is Amazon Web Services, is also concerning. Organisations such as the ETUC are calling on public authorities to explore alternatives to the big corporate cloud and infrastructure providers (Microsoft Azure, AWS and Google Cloud), and seek to develop independent public alternatives.[15] The EU is already looking at aspects of this through the GAI-X project, a collaboration between the European Commission, France and Germany and various organisations (including businesses) on the continent, which aims to tackle issues around data sovereignty and GDPR compliance, through a trusted public cloud offering that addresses the needs of the public sector.[16]

Tax reform

More broadly the UK, EU and OECD have been looking at tax reform in a digital age, with over 130 countries signing up to the OECD ‘Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting’ (BEPS).[1] There are two central pillars to the BEPs framework, the first being the re-allocation of profits and nexus rules, aimed at determining where tax should be paid and on what basis. Users of digital services create huge value for tech companies, but currently they are only taxed where they have a physical presence, not necessarily where they create value. The BEPs aims to tackle that. The second pillar focuses on global anti-base tax erosion, with the aim of designing a system whereby all multinationals pay a minimum level of tax to combat profit shifting to low tax jurisdictions.

In April this year, the UK introduced a digital services tax of 2 per cent on the revenues of search engines, social media services and online marketplaces which derive value from UK users.[2] However there have been reports that this tax may be abandoned to help secure a trade deal with the US, something denied by the Treasury.[3]

The European Commission launched its ‘Fair taxation for the Digital Economy’ paper in 2018, with a final report due before the end of the year.[4] In line with the OECD BEPS initiative, the EU is proposing reforms to corporate tax rules so that profits are registered and taxed where businesses have significant interaction with users through digital channels, and profits are attributed to member states so the system better reflects where companies create value online.

In Australia, the government changed sales tax regulation to require businesses earning more than $75,000 AUD a year to charge a 10 per cent sales tax on low value products imported by customers. This resulted in Amazon blocking Australian users from having access to its US site. But after six months Amazon backtracked on the blocking decision[5], reinforcing the fact that no matter how big they are, it needs customers.

More people are beginning to understand the scale and reach of Amazon and the implications of its unchecked power.

Taking on Amazon will require a combination of new regulation appropriate for a digital economy, enforcing existing legislation and empowering unions, and enabling governments, both local and national to hold them and others to account.

As former Amazon vice president Tim Bray said:

“Amazon is exceptionally well-managed and has demonstrated great skill at spotting opportunities and building repeatable processes for exploiting them. It has a corresponding lack of vision about the human costs of the relentless growth and accumulation of wealth and power. If we don’t like certain things Amazon is doing, we need to put legal guardrails in place to stop those things. We don’t need to invent anything new; a combination of antitrust and living-wage and worker-empowerment legislation, rigorously enforced, offers a clear path forward.”[6]

We have outlined the many ways in which Amazon creates its unfair advantage. Rather than building a healthy and fair system, both online and within the communities it operates in, often, its practices stifle workers’ rights, fair competition and the ability of governments to hold it accountable.

Therefore, a key challenge is holding Amazon to account and ensuring that its growing presence in the UK is not accompanied by the undermining of communities, local governance and workers’ rights

This is particularly important when the Covid-19 pandemic and economic downturn could strengthen the hand of those companies offering to bring jobs to an area.

As part of our research for this report we looked at Amazon’s relationship with local government to illustrate its current power and growing influence and its impact on local employment conditions. We suggest areas for change in order to give local authorities more agency when dealing with Amazon and make Amazon more accountable.

The pressure on local authorities to keep existing jobs and bring new jobs into their areas, as well as find ways to support their already cash-strapped budgets is going to be immense. Likewise, while Amazon continues to benefit from the pandemic, other retailers, faced with an economic crisis and adapting to the continued risk to public health, will struggle to keep afloat.

We also know that our high streets are changing and how they will look and be used in the future is uncertain. This challenge is not new. But the Covid-19 pandemic has almost certainly exacerbated existing trends towards a greater share of sales coming from online as opposed to bricks and mortar stores, making the need to support local government in developing sustainable high street renewal and jobs even more urgent.

By focussing on local government relationships with Amazon to date, we hope to contribute to the discussion about how we can support authorities in bringing good employment and fair working practices to their communities; ensure that social value and ethical supply chains are embedded throughout the employment and procurement processes; and enable local authorities to get the best outcomes for their citizens and communities.

What we did

To build a picture of Amazon’s reach into local government and the agency local authorities have when dealing with it, we looked at two aspects of Amazon’s presence in the UK – employment and procurement.

First, we sent Freedom of Information requests (FOIs) to 55 local authorities that have an Amazon site (distribution centre, development centre or delivery hubs and lockers) asking the extent to which local authorities had had any oversight or input into establishing Amazon in the area, either through the planning process or through other negotiations and engagement with Amazon.

We specifically wanted to know if any consideration or assurances had been given regarding employment rights and fair working practices (such as union recognition, fair notice periods, living wages and health and safety).

Second, we wanted to know the extent to which local government mirrors central government in increasing their spend with Amazon, particularly through the award of public procurement contracts. Here we commissioned research jointly with GMB to look at procurement contract awards and day-to-day spending. We followed this up by sending FOIs to individual local authorities that had particularly high spending levels and/or had awarded significant procurement contracts to Amazon, asking whether any weighting had been given to social value criteria (see box 4) in the procurement process as required by the public contracts regulations 2015. And, if so, what criteria were used and how Amazon demonstrated its commitment to them.

Box 4: Social value in the procurement processSocial value in procurement and commissioning refers to using the leverage public bodies have as purchasers of goods and commissioners of services to help to achieve economic, social and environmental goals. Within this broader strategy, public procurement can be used to promote good work through the contracting process. Permissive legislation, including the Public Services (Social Value) Act, the Public Contracts Regulations 2015, the Equality Act 2010 and public procurement legislation in Wales and Scotland provides the scope for more action on good work – enabling public bodies to move away from price-based competition and incorporate broader social, environmental and employment considerations where this is relevant to the nature of the contract. And while this potential has yet to be fully exploited, we are seeing things moving in the right direction. We believe public procurement can be a key tool in promoting good work as part of a wider strategy across government that could also include:

|

What we found out

Employment

To date we have had 47 responses to our FOIs. We began this research in early March, just before the coronavirus pandemic. This responses to our requests.

Of the responses we have received, a couple of local authorities had had some significant engagement with Amazon regarding employment.

One local authority had worked with Amazon to draw up an employment and skills plan as part of a planning condition for Amazon to occupy the premises in 2017. The city council’s skills and growth manager worked with Amazon to draw up the plan. Once the plan was agreed the City Council’s ‘Employment Hub’ supported local recruitment of staff including hosting recruitment events.

The employment and skills plan included commitments to:

- promoting accessible opportunities for local people

- use training to support skills development and a qualified, competent, motivated workforce

- engage with local business and community needs

- work with local actors including the council, job centres and other employment schemes, maximising the legacy benefit through long term employment.

The plan also commits to training and apprenticeships through Amazon’s apprenticeship scheme as well as monitoring on progress through annual updates for the first five years. We followed up on this with another FOI requesting to see any available progress reports. Unfortunately, Amazon owns this data so the local authority in question were unable to share these with us.

Similarly, another local authority had engaged with Amazon through their Skills Company with the aim of supporting the council and neighbouring authorities to get long-term unemployed residents back into the workplace. Running alongside Amazon’s usual recruitment process, a pre-employment course was provided to residents in order to prepare them for applications and Amazon recruitment events.

Amazon also worked with this local authority to produce an employment and skills plan which aims to:

- raise aspirations and engagement, promoting participation in education and training

- support education providers to design relevant curriculum and training and align career choices and guidance with employment available

- provide opportunities such as employment, supported employment, work experience, apprenticeships, traineeships, internships, mentoring and volunteering for a range of ages and abilities

- support the local labour force by training residents to give them skills and qualifications needed

- engage with local businesses, develop local supply chains to proactively source local suppliers; buy local goods, trades and services

- engage with the local community to address specific local needs

- build a sustainable relationship and legacy between all stakeholders including the developer/owner, employers, partners, local community, businesses and residents.

Again, when we followed up with another FOI regarding the monitoring of this plan, the council confirmed that responsibility for implementation and therefore monitoring lay with Amazon.

Another council had liaised with Amazon and other employers through participation in local jobs fairs and their employment support team worked in conjunction with the DWP to invite Amazon to jobs fairs and Job Centre meetings with job seekers between April and October 2019. Amazon also met with a local works project to discuss engagement with schools to deliver coding sessions.

Other responses suggested that local authorities had had little engagement or agency regarding Amazon as they established themselves in their areas. One FOI response said:

“The client signed an NDA with their agent CBRE, who did not disclose to us who their client was until after the land acquisition deal was signed.”

Others suggested their involvement typically stemmed from health and safety complaints, whereby councils would only engage once a complaint is received or incident has occurred.

Some councils made clear that employment rights or working practices are not typically part of the planning process, with one response stating that the council held “…no information regarding this. Employment rights are to do with the company itself".

What does this tell us?

Our research suggests that where there has been engagement with Amazon on employment, it has focussed more on job creation and developing skills to meet Amazon’s criteria. Job creation is an important goal for local authorities, and it is to be commended that some councils have managed to build some form of relationship and have some input through employment and skills plans. But evidence suggests that Amazon controls the monitoring of these commitments so there is no way of knowing if they are delivering on their promises. More needs to be done to ensure that councils can guarantee that good quality jobs, employment rights and accountability from Amazon (and others) are part of the deal as well as other social value goals.

Another theme to emerge from the research is the inconsistency and complexity of the planning system. While there are examples of councils making employment and skills part of the criteria of the planning process, this is not consistent and as discussed does not necessarily focus on employment rights and fair working practices. This can be further complicated by the number of parties involved, who owns the land and whether Amazon is directly leasing from the council or through a third party, as demonstrated by one response which stated:

“The site is privately owned and so we have no authority to ask that the criteria stated was agreed to by Amazon as they are a private tenant and any agreements were between Amazon and the developer. We cannot confirm or deny that they have implemented any of the stated criteria, as again we have no authority to request this information.”

As we outlined in chapter two, there are many reports of poor employment practices at Amazon from bogus self-employment of drivers, employees being fired with no consultation, extensive surveillance, gruelling working conditions that jeopardise people’s health, health and safety violations in general and particularly during the coronavirus crisis and actively working against unionisation. As Amazon expands its workforce in the UK it is vital it can be challenged to do better to give workers security, safety and dignity at work.

Procurement and spending

Amazon’s reach into local government is not yet as widespread as it is at central government level.

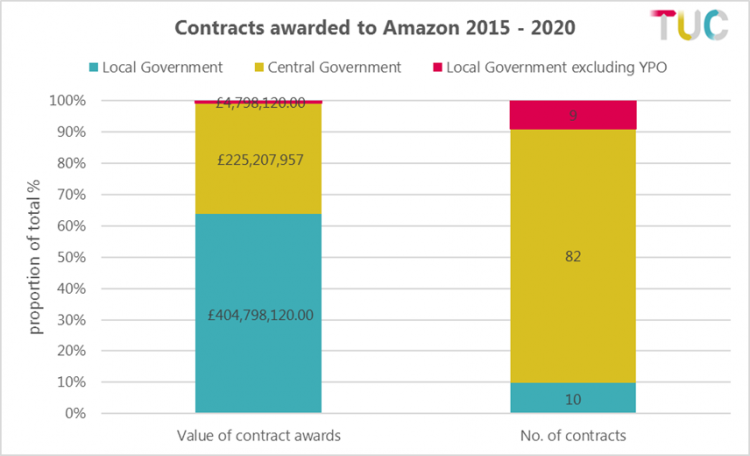

Research commissioned with GMB from Tussell Ltd, showed that between 2015 and May 2020, Amazon were awarded 92 public sector contracts (for both national and local government) with a lifetime value of up to £630 million pounds. The majority of these have been awarded since 2017 and are for Amazon Web Services (cloud related infrastructure and services), with a notable exception of the Yorkshire Purchasing Organisation (YPO) framework agreement, potentially worth up to £400 million over the life of the contract for the creation of a digital marketplace for the 13 local authorities that are covered by the YPO.[1]

More common at local level is smaller spending through the Amazon marketplace (which does not have to go out to tender as it is below a certain threshold), albeit the value is low.

Contract awards

Central government has awarded 82 contracts (89 per cent) to Amazon over this period with a lifetime value of over £225 million. In contrast local government has awarded only 10 contracts, but due to the YPO contract the potential lifetime value of these awards is nearly £405 million. Excluding the YPO, Amazon has still gained nearly £5 million in contract awards from 4 local authorities and TFL.

Public Contract awards to Amazon

As the YPO contract is a sizeable contract at local government level we also sent a Freedom of Information Request to establish to what extent social value criteria and ethical trading standards in the supply chain had been considered.

In response to our request the YPO referred us to the VEAT Notice (voluntary ex-ante Transparency notice)[1] and PIN (Prior Information Notice)[2] made publicly available and to section 32 of the Public Contracts regulations[3].

The Original PIN states in section 11.2.3:

Potential providers would need to meet the following criteria in order to participate in the pre-market engagement phase, and move on to the full tender process:

- single point of access for suppliers and customers,

- clarity of customer order, payment, fulfilment, and returns options,

- an established B2B marketplace presence,

- a diverse range of products which includes but is not restricted to curriculum resources,

- management of procurement authorisation levels,

- comprehensive cyber security.

The VEAT notice states that following the publication of the Prior Information Notice, the YPO only received one ‘compliant expression of interest’ and that:

“The proposed contractor, being an established mature B2B marketplace provider with a range offering of over 1 000 000 products from thousands of sources, is both the only contractor capable of achieving the desired economies of scale required to bring all spend within one portal to generate significant cost benefits to YPO's permissible users and the only viable contractor currently operating in the market for the products and service requirement requested.”

So, Amazon was considered the only viable option for this type and scale of contract. Under section 32 of the Public Contracts Regulations, contracting authorities may award public contracts by negotiated procedure without prior publication in some circumstances, including where the works, supplies or services can be supplied only by a particular economic operator due to the absence of competition for technical reasons.[4]

This demonstrates very clearly the challenge posed by Amazon’s scale and scope. It has built its effective marketplace monopoly by providing a platform for third party sellers, gathering information and using it to grow its own product range as well as making it the only viable place for sellers to operate through. In doing so, it has now become so big that no other platforms can compete with it in terms of scale, therefore crowding out the competition and making organisations feel there is little choice in who they deal with. It has become something of a self-fulfilling procurement prophecy.

In responding to our FOI request the YPO were able to give us sight of a redacted copy of its framework agreement as well as a copy of their Ethical Trading Policy.

The Ethical Trading Policy states the policy aims as:

- ensuring that social, ethical, environmental and economic impacts are considered in decision-making throughout the organisation

- providing a single reference to legal and regulatory requirements for ethical business practice

- setting baseline standards for procurement decisions

- providing a framework for other social, environmental and ethical activity

- committing to management review and continuous improvement of ethical practices.

The document states that the policy will achieve this by, committing to several measures as a minimum, including:

- committing to high ethical standards in all its activities

- promoting the value of human rights and equality within its supply chain

- working with responsible suppliers to understand their supply chains and products including seeking assurance of the sustainability, environmental performance and ethical standards on initial contact and in tenders

- working more effectively with local, smaller and more diverse suppliers to ensure that such businesses are not excluded from bidding for YPO business.

Knowing what we know about Amazon, it is difficult to see how it would have met these criteria, but as the VEAT declared, there appeared to be no other viable option for the contract. The framework agreement itself refers to social value stating a commitment to non-discrimination under the terms of equality law and also states:

“The supplier shall, and at all times, be responsible for and take all such precautions as are necessary to protect the health and safety of all employees, volunteers, service users, and any other persons involved in, or receiving goods from, the Call-Off Contract and shall comply with the requirements of the Health and Safety Act 1974 and any other Act or Regulation relating to the health and safety of persons and any amendment or re-enactment thereof.”

And:

“YPO will alert the Supplier by email or through their account manager of any Goods that do not meet Good Industry Practice or where YPO suspects infringement of any of its Selling Policies and Seller Code of Conduct provisions in relation to child labour, involuntary labour, human trafficking, slavery, working environment health and safety, wages and benefits, working hours, anti-discrimination, fair treatment of workers, immigration compliance, freedom of association and ethical conduct.”

There are some clauses referring to workers’ rights and ethical behaviour, but whether these could allow for the raising of concerns in a broader sense and not just specific to the delivery of the contract is questionable. Nor is it clear, given the vast array of suppliers and products, how anyone ordering through an Amazon Business framework could prove exactly where their goods had come from or whether there had been any infringement of worker rights or ethical conduct in the process.

The Framework agreement between the YPO and Amazon states clearly that it is a non-exclusive contract – so authorities do not have to purchase through the digital marketplace. But as is the case with many consumers, it feels increasingly difficult to avoid them and as the data on spending set out below shows, local authorities are spending through the Amazon marketplace for day to day goods.

Spending at local authority level

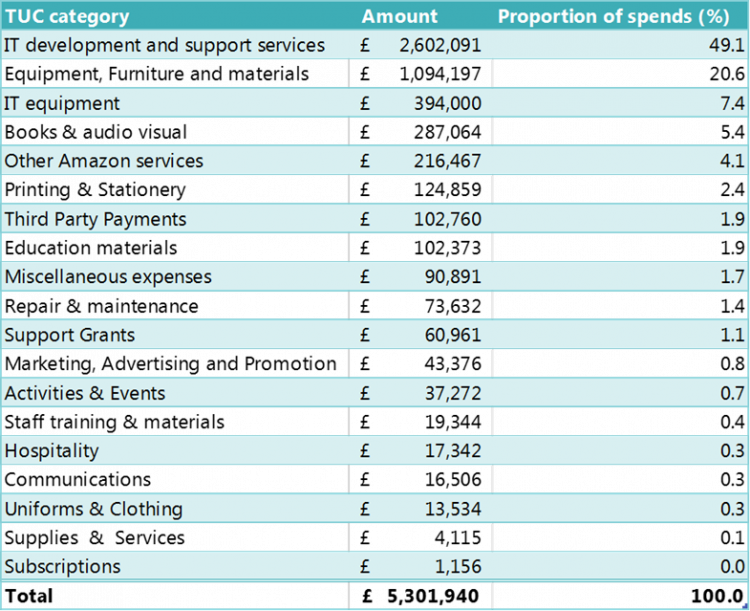

Local authorities are required by law to publish any expenditure above £500, this can be done monthly, or quarterly. Local authorities can publish spending below the £500 threshold, but they do not have to. The research we commissioned with GMB returned 52,000 individual spends between 2017 and early 2020 across 70 different local authorities at a value of £5.5 million, though most of the spending was driven by 7 local authorities.

The value is low in comparison to the large contracts from central government and the large contract from the YPO, but it does demonstrate the type of products and services local authorities are purchasing, mostly through the through the marketplace**, and as we noted local authorities are not obliged to publish transactions with a value of less than £500, so the total figure may not fully capture all purchases or the extent of spending through Amazon.

Spending on AWS related software and support has grown significantly between 2017 and 2019 – local authorities were only spending around £22,000 in 2017, by 2019 that had risen to just under £900,000.

More than half (56.5 per cent) of spending with Amazon is for the purchase of IT equipment and development and support services, and just over a fifth of spending is for equipment, furniture and materials (covering all equipment purchases excluding IT and including things like catering equipment, office furniture and equipment, tools for maintenance, mobile phones). Some 10 per cent of spending goes on books, audio visual, stationery, printing and educational materials.

As is the case with many consumers, Amazon is the first place people often look when they want to buy something online. Local governments may increasingly reflect general trends towards using the ‘Everything Store’ because of its convenience and perceived competitive pricing (YPO noted on announcing the contract, 80 per cent of their customers already used Amazon and the aim was to reduce fragmentation of spending and deliver a ‘one stop shop’ proposition).[1]

But as we raised in chapter two – Amazon is known for its unscrupulous practices in the marketplace. Reports of bullying third party sellers, using anti-competitive tactics to dominate the market, not having any clear strategy for policing the quality of what is being sold on its platform are common, nor is it clear that they really are delivering the best prices for customers.

In the US, where Amazon has been awarded a contract through U.S. Communities, an organisation that negotiates joint purchasing agreements for its members, many of which are local governments, one report from the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) suggests that local authorities could be paying 10-12 per cent more by buying through Amazon, rather than through local suppliers.[2] While the US obviously has a different system to the UK, the evidence increasingly suggests that the assumption that Amazon is the best on price is not necessarily true.

The ISLR report also indicated that as well as failing on price, the way in which the contract was proposed favoured Amazon, hobbling the ability of others to compete for the contract and by awarding to Amazon created a situation where others will increasingly have to go through the Amazon platform as third party sellers in order to reach government buyers.

The Institute for Local Self-Reliance argue:

“The contract lacks standard safeguards to protect public dollars, and puts cities, counties, and schools at risk of spending more and getting less.

The contract also poses a broader threat. Amazon is using the contract to position itself as the gatekeeper between local businesses and local governments. As it does so, it’s undermining competition and fortifying its position as the dominant platform for online commerce.”[3]

As the YPO contract demonstrates, this is clearly not just a problem in the United States. One report commenting on the YPO-Amazon Business announcement highlighted the risk that it could disrupt the market and put pressure on sellers wishing to engage with public sector buyers to go through Amazon’s seller programme[4]. Similarly, a representative from the British Healthcare Trades Association, regarding the contract stated:

“This development indicates the potential direction of travel for more aspects of public sector procurement. In the meantime, businesses may see this as an opportunity for them to supply or purchase products in a convenient way, but it may also be a threat to other models of procurement.”[5]

Amazon’s legal team had a significant hand in writing the terms of the US communities’ contract and included restrictions on Freedom of Information requests which compromise public transparency. While we have had full cooperation with our requests to local authorities here in the UK, there was some information that was restricted by Amazon as the data controller or under the terms of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 because it was deemed commercially sensitive. And in the YPO Framework Agreement it states that the YPO will notify the supplier (Amazon) as soon as practicable, or within three working days upon receipt of any requests for information under the Freedom of Information Act. Details of the request must also be shared and before any information is disclosed, the supplier should be allowed to representations regarding the disclosure and must be considered.

What does all this mean?

Much of Amazon’s activity in the UK is of course unrelated to local and central government. But as bodies that should have a key interest in promoting decent employment rights, we have chosen to focus on their direct interactions with Amazon to investigate the extent to which this might be a lever for change.

The information we have been able to gather suggests that Amazon is growing as a supplier to central and local government, but that while there is some engagement on jobs, engagement on rights is patchy. Given the many challenges that Amazon’s business model poses to decent work in the UK, the next section examines what more government could do to address these concerns.

Amazon’s ‘Everything Store’ front was never just about retailing and today Amazon is much more than the online retailer of everyday goods. As its retailing arm grew, so did Amazon’s ability to gather, analyse and monetise the data of its users, and in doing so Amazon not only cemented its position as gatekeeper to the market place of things, but also enabled its expansion into logistics, technological development and cloud services.