TUC Equality Audit 2022

Winning equality is at the heart of our cause to change the world of work for good. That’s why the TUC’s annual equality audit matters. It helps us track our collective progress and spurs us on to do even better.

And the 2022 audit is published at a significant moment. The Covid-19 pandemic has shone a light on the multiple inequalities that exist across our society – and exacerbated them. Covid-19 has exposed the inequality affecting BME and disabled workers, all too often with fatal consequences. LGBT+ workers’ mental health and wellbeing has suffered as they have been distanced from support networks. And women have been on the front line as key workers, they have taken on the brunt of caring responsibilities, and have faced the extortionate cost of childcare.

Workers are also experiencing a cost-of-living emergency as soaring inflation drives up the price of our food, energy and housing. Because of existing structural inequalities, groups with protected characteristics are likely to be hit hardest. Women, disabled workers, LGBT+ workers and BME workers all face a pay gap, meaning they have less money to cover rising costs.

We need a government that will stand up for working people, but instead we have seen chaos. Rather than addressing the crisis facing the country, the government is spoiling for a fight with workers who take action to defend their living standards. As City bonuses and top pay once again spiral out of control, ministers have failed to deliver on their promises to raise wages. This winter, millions will face the unpalatable choice between heating and eating.

Over the past four years, we have witnessed a global conversation on sexual harassment in the wake of the MeToo movement. And since the murder of George Floyd in 2020, we’ve seen the emergence of a global struggle for racial justice. But trade unions must be honest: we have to fight on two fronts. Racism and sexism are not confined to the bosses. If we are to change society, we must also overcome discrimination within our own ranks.

That’s why I’m proud we’ve launched our Anti-Racism Taskforce, which will help our movement to practice what we preach on race equality. I’m proud too of our work on sexual harassment, supporting the TUC and unions to become genuinely safe, inclusive and welcoming spaces for women members, activists and leaders.

This audit provides inspiring examples of what we’re doing to put equality at the heart of our agenda. It highlights union action to combat all forms of harassment, discrimination and prejudice. It underlines what we’re doing as employers and within our own democratic structures. But the audit also highlights where we need to raise our game.

This is my last equality audit before I retire, and I hope it inspires affiliates to organise, bargain and campaign for change. Over the past 10 years, I’ve been enormously proud of the work we’ve showcased in our equality audits – and everything we’ve done as a movement to build a fairer, more equal, more just world. From the equal pay strikes to our response to the pandemic, we’ve made a genuine difference to marginalised groups of workers. Let’s use this audit as a springboard to win equality for all our members – because now, more than ever, we demand better.

Frances O’Grady TUC General Secretary

The TUC Equality Audit 2022 considers the steps unions are taking to promote equality in their membership, structures and processes, and to ensure they reflect the diversity of their membership.

It provides examples of how unions are recruiting and supporting underrepresented groups into membership and activism and looks at what unions are doing to give these groups a voice within the movement.

We sent questionnaires to 48 unions affiliated to the TUC, of which 85 per cent completed it and this report provides the results. The executive summary focuses on three key themes we felt it was important to pull out: voice; the quality of monitoring data; and sexual harassment.

Voice for equality groups in our movement

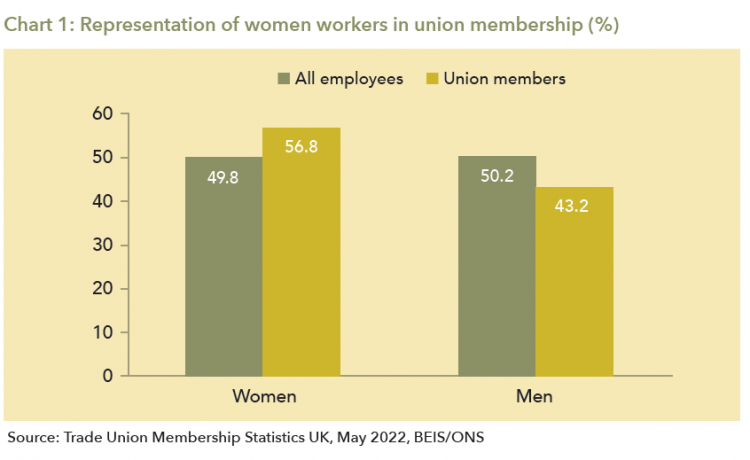

Trade union membership statistics from BEIS and the ONS for 2022 shows us our membership is diverse, but there is work to do. 56.8 per cent of union members are women and disabled workers account for 15 per cent of employees but 18.9 per cent of union members.

But overall BME employees are underrepresented in union membership, though the picture is complex: Black/Black British workers are slightly overrepresented among union members, while Asian or Asian British and Chinese workers are underrepresented. Young workers continue to be underrepresented in union membership and unfortunately there is still no national level data on LGBT+ union membership.

It is important that unions continue to recruit members from all demographics to ensure our membership is reflective of the working population, but we must also ensure they are given voice within our structures via our equality committees, reserved seats, conferences and rep and activist roles. The audit provides a wealth of examples of where unions have proactively updated rules to increase representation in structures or run campaigns to recruit new reps.

The data on the demographic characteristics of union reps and activists is patchy, but the pattern emerging is that women and BME workers are underrepresented in union rep roles, though with some exceptions. For example, BME members are proportionately represented in equality rep and learning rep roles.

The 2022 audit also found that the proportion of unions with formal bodies e.g. committees and networks for each of the equality strands, has fallen since 2018, but that there has been a growth in informal networks, in particular for BME members (54 per cent of unions compared with 37 per cent in 2018). Informal networks have arisen both spontaneously by members and initiated by officers, and in some cases in response to external events such as the pandemic or the Black Lives Matter movement.

The growth of informal networks is positive and provides opportunities for members to become more involved in the union. However, this growth should not be at the expense of formal networks, which feed into democratic structures.

The audit also shows a mixed picture when it comes to equality conferences. There has been a fall in the proportion of unions holding national conferences for overall equality, women and disabled and young members since 2018, when there had already been a decline since 2014. However, the proportion of unions holding national conferences or seminars for BME members has increased, and the number holding LGBT+ events stayed the same. We must ensure spaces to prioritise and debate key issues for equality groups are not lost.

Positively, the audit shows a growth since 2018 in the number of unions with reserved seats on national executive bodies across all equality strands.

The 2022 audit presents a mixed picture on the multiple ways members can have a voice within their union and as a movement we must ensure we develop more ways to encourage this and protect those that we have.

The quality of monitoring and data collection

One of the limitations in understanding where different equality groups are active in the union movement and whether unions truly represent the full diversity of our membership is the sometimes patchy data unions collect on members and in particular activists. Collecting data and understanding where those with protected characteristics are within our movement is the first building block to addressing inequality. Without data we cannot know or understand where the problems are, or if underrepresentation exists to then tackle it.

The audit found that the majority of unions do collect data on the number of women (85 per cent), BME people (59 per cent), disabled people (56 per cent), LGBT+ people (59 per cent) and young people (61 per cent) in their membership. The unions collecting data on disability and LGBT+ identity has increased significantly since 2018.

However, not all unions that collect data are able to state confidently how many of each demographic group there are at a given time because the data often comes from a sample of members or activists rather than the entire membership.

The audit notes that there has been growth in the number of unions conducting monitoring of reps and activists since 2018 but it is still lower than the number of unions collecting membership equality data and, again, there are problems with accuracy.

Unions have made progress on data monitoring and the audit provides key examples of where unions are improving on this. Looking to the next audit, we as a movement must take steps to improve the quality of our monitoring so we can truly understand representation in our unions and, importantly, where different groups have a voice or lack of it.

Sexual harassment

For the first time, affiliates were asked if they had done any specific work in the last four years to prevent sexual harassment of their staff, alongside longstanding questions on bullying and harassment. The addition of this question is to follow progress since the creation of the TUC General Council statement and guidance on sexual harassment in 2018 and the establishment of the Executive Committee working group on sexual harassment in 2021. The group aims to support unions to tackle sexual harassment within their own structures and within our wider movement by building preventative cultures.

The working group has developed a framework and supporting materials for leaders of our movement. These resources are intended to guide their work towards tackling, preventing, and responding to sexual harassment in their organisations and have been rolled out to the TUC and affiliates. This was alongside the production of research and resources to tackle sexual harassment across all employers. The working groups also have commitment to find out what unions are doing in this area and share best practice.

The questions in the audit form part of this work. Fourteen unions told us they had done specific work to prevent sexual harassment of staff in the last four years, 31 unions said they had rules or procedures covering allegations of discrimination or harassment made against its lay activists, officers and full-time officials and 34 unions had an explicit reference to dealing with harassment/discrimination within their internal complaints, disciplinary or grievance procedures.

The audit contains examples of the work unions have been doing on sexual harassment that can be used as examples for others, but the findings also show the work needed to ensure all unions are taking specific action to prevent sexual harassment of their staff and across their structures.

The TUC Equality Audit 2022 considers the steps unions are taking to promote equality in their membership, structures and processes, and to ensure they reflect the diversity of their membership.

It also looks at the extent to which unions as employers provide equal opportunities for their own staff. It is complementary to the TUC Equality Audit 2020–21, which looked at unions’ efforts to promote equality through collective bargaining.

Questionnaires were sent to the 48 unions affiliated to the TUC in November 2021, with a completion deadline of 1 February 2022. Completed questionnaires were received from 41 unions, which is 85 per cent of TUC affiliates. This is a higher response rate than for the last equivalent audit in 2018 when 38 out of 50 TUC affiliates participated (76 per cent). And it is higher than in 2014, when 36 out of 54 TUC affiliates completed the audit (67 per cent). But more needs to be done to ensure a high return rate continues in the future.

While all TUC unions were sent the main audit questionnaire, those with fewer than 12,000 members were given the option of completing an abbreviated version of the questionnaire. This version was chosen by four of the 41 respondents: AEP, Napo, NSEAD and RCPod.

The unions responding in 2022 represent 99 per cent of all TUC-affiliated union members. The audit data was collected and analysed by the Labour Research Department on behalf of the TUC.

Please note the language used to describe different equality strands (e.g. BME, BAEM or LGBT+, LGBTI) in examples is the language used by the union that provided the example.

This section looks at the degree to which different workers are represented in trade unions. It makes use of the most recent official statistics relating to trade union membership among women, BME, disabled and young workers.1

There is no official data for LGBT+ workers in union membership.

The figures show that women, Black/Black British, white, disabled and older workers are overrepresented in union membership while underrepresented are male workers, those from other ethnic minority groups, non-disabled workers and younger workers.

Women

Women employees are overrepresented in union membership. As chart 1 shows, in 2021 56.8 per cent of union members were women, despite accounting for 49.8 per cent of employees.

- 1 Trade Union Membership Statistics UK, May 2022, BEIS/ONS

Since 2002, union density has been higher among women employees than men employees and in 2021 it was 26.3 per cent for women compared with 20.0 per cent for men.

In part the higher union density among women in the past two decades reflects higher female employment rates in the public sector, where union density is much greater. Over half (50.1 per cent) of public-sector employees are union members compared with just 12.8 per cent of private-sector employees. However, in the latest period (2020–21) union density among women overall fell slightly for the first time since the publication of the 2018 TUC Equality Audit. This was mostly because of a fall in union membership in the public sector.

Trade union density among women is highest for those in professional occupations. 46.8 per cent of women in professional occupations are union members compared with 23.3 per cent of men. Teachers, midwives and nurses are women-dominated professions that are highly unionised.

Meanwhile, 26.4 per cent of women in caring, leisure and other service occupations are union members, as are just 16.4 per cent of women in sales and customer service jobs and only 13.0 per cent of women in ‘elementary occupations’. In sectors such as caring, leisure, other service occupations and elementary occupations union density is significantly higher among men.

Women in some types of employment are underrepresented in union membership. Women are more likely than men to work part time (73 per cent of part-time workers are women2

) and part-time workers are underrepresented in trade unions. Those working part time form 23.6 per cent of employees but 21.8 per cent of union members.

Union density among women in temporary jobs is 17.5 per cent – substantially higher than the 12.1 per cent figure for men in temporary jobs. However, the level is still well below the 26.3 per cent among women employees overall, and women are more likely than men to be in temporary jobs (6.9 per cent compared with 5.1 per cent of men).

BME workers

BME employees overall are underrepresented in union membership. While they account for 13.3 per cent of all employees, they make up just 11.8 per cent of union members. In contrast, white workers form 86.7 per cent of the total employee population but 88.2 per cent of union membership.

However, Black/Black British workers are slightly overrepresented among union members. They account for just 3.4 per cent of all employees but 3.8 per cent of union members. And employees from a mixed ethnic background are fairly represented – accounting for 1.4 per cent of both employees and union members.

But the largest BME group of employees – Asian or Asian British – account for only 5.2 per cent of union members despite forming 6.3 per cent of the employee population. Meanwhile, those identifying as Chinese or from another ethnic group constitute 2.2 per cent of the employee population but just 1.4 per cent of union members.

- 2 EMP01 SA: Full-time, part-time and temporary workers (seasonally adjusted), ONS May 2022.

Union density is highest in the Black or Black British ethnic group (29.0 per cent), followed by the White ethnic group (23.3 per cent). Among those of mixed ethnic background it is 20.6 per cent and among Asian and Asian British employees it is 20.3 per cent. Density is lowest among the ‘Chinese or other ethnic group’ employees, at just 15.3 per cent.

Union density is higher among women than men in all ethnic groups. When union membership data is broken down by both ethnic group and gender, the highest union density of all is among Black/Black British women, among whom 30.3 per cent are union members.

Disabled workers

Disabled employees acknowledged under the Equality Act 2010 definition are overrepresented in union membership, accounting for 15 per cent of employees and 18.9 per cent of union members.

Disabled employees are also more likely to be union members, with a union density of 28 per cent compared with 22.2 per cent among non-disabled employees.

This may partly be due to the fact that they are more likely than non-disabled employees to work in the public sector, which has a higher union density than the private sector. Government data shows that in 2021 26.5 per cent of disabled employees worked in the public sector compared with 23.1 per cent of non-disabled people.3

However, disabled people are underrepresented in the workforce generally. The disability employment rate was just 52.7 per cent in 2021, compared to 81 per cent for non-disabled people.

LGBT+ workers

Unfortunately, there isn’t data on LGBT+ workers and union membership. The Government Equalities Office conducted a national LGBT survey in July 2017 that analysed responses from 108,100 individuals who “self-identified as having a minority sexual orientation or gender identity, or as intersex”.4

It found that 80 per cent of respondents aged 16–64 had had a paid job in the 12 months preceding the survey, a figure described in the report as “broadly consistent” with the general population.

However, the survey also found that trans respondents aged 16–64 were much less likely to have had a paid job in the 12 months preceding the survey than cisgender respondents (63 per cent did so compared with 83 per cent).

Young workers

There remains a large shortfall in the representation of young employees among union members. Those under age 35 account for 36.8 per cent of employees but just 24.1 per cent of union members. In contrast, those aged 35 or over account for 63.2 per cent of employees but 75.9 per cent of union members.

The distribution of union membership by age group also reflects the pattern of union density according to length of service with their current employer. For example, while just 15.6 per cent of those with one to two years’ service are union members, this figure doubles (31.6 per cent) for those with 10–20 years’ service.

TUC rules require unions to show a clear commitment to equality for all and to eliminate all forms of harassment and discrimination within their own union structures and through all activities.

One way of showing this commitment is by adopting the TUC model equality clause (see box).

Three-quarters of the unions responding to the audit (76 per cent) have specifically adopted the TUC model equality clause. Unions in the small-sized band 5

are more likely (81 per cent) to have adopted the clause than medium unions (79 per cent) and large unions (50 per cent). Overall, 72 per cent of members of unions responding to the audit are covered by the clause.6

Just over half (51 per cent) of unions responding to the audit have introduced new national rules on equality in the last four years.

Unite has introduced a swathe of new rules in that period. For example, its policy and rules conferences now have additional LGBT+ and Disabled delegates elected from each region.

Unite also changed some terminology in its rules, so that ‘Female’ became ‘Woman’; ‘Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority’ became ‘Black and Asian Ethnic Minority’; and ‘LGBT’ became ‘LGBT+’. In other wording changes, BFAWU has removed all references to ‘he/she’ in its rulebook and replaced them with ‘they’ and the UCU has replaced the term ‘transgender’ with ‘trans’, added ‘+’to the ‘LGBT’ abbreviation for greater inclusivity. UCU has also added ‘gender identity’ to the personal characteristics covered by its rules protecting members from harassment and discrimination.

In 2019 and 2021 the CWU introduced rule changes to increase the number of women, BAME, disabled and LGBT+ activists on its national executive committee. In addition, a rule has been introduced guaranteeing women’s representation for regional principal officer roles, such as regional chair, regional secretary, regional finance secretary and assistant regional secretary. The rule specifically outlines that at a minimum two women will hold principle regional roles in each of its 10 regions.

The union also introduced under rule new regional equality lead positions for women, BAME, disabled and LGBT+ members who are members of the regional executive committee (see section on equality officers).

Other rule changes of this sort are looked at in the relevant specific sections of this report.

Just under half (46 per cent) of the unions responding to the audit have a rule related to membership of far-right or racist political parties. The large unions (83 per cent) are much more likely to have such a rule than the small (43 per cent) and medium unions (36 per cent).7

81 per cent of all members of unions responding to the audit are covered by such rules.

- 5 See the Notes section for size definitions

- 6 The three large unions with such a clause are NASUWT, UNISON and Unite. Eleven medium unions have adopted the clause, namely Community, CSP, CWU, EIS, Equity, NAHT, PCS, POA, Prospect, RMT and UCU. And 16 small unions have adopted it: Accord, AEP, ASLEF, AUE, BFAWU, BOSTU, BALPA, FDA, Napo, NARS, Nautilus, NGSU, NSEAD, NUJ, PFA, RCPod and SoR.

- 7 The unions with rules in this area include: five large unions (83 per cent) – GMB, NASUWT, NEU, UNISON and Unite; five medium unions (36 per cent) – CWU, FBU, MU, PCS and UCU; and nine small unions (43 per cent) – Accord, ASLEF, AUE, BFAWU, BOSTU, Nautilus, NGSU, NUJ and NUM.

The UCU has added the German AfD to the list of proscribed far-right groups under its rule in this area. And, as foreshadowed in the 2018 audit, Accord’s conference decision to allow membership to be rejected based on member misconduct or being a member of an organisation with objectives contrary to that of the union (such as far-right groups) was incorporated into its rules at the next conference.

Discrimination and harassment rules and procedures

This section looks at union rules and procedures covering allegations of discrimination or harassment made against its lay activists, officers and full-time officials (as opposed to union-as-employer policies designed to protect union staff, which are covered in section E).

Overall, 31 of the unions responding to the audit (76 per cent) said they had such rules or procedures. All six of the large unions responding to the audit had such rules, as well as 10 (71 per cent) of the medium unions and 15 (71 per cent) of the small unions. A very high proportion (96 per cent) of the members of unions responding to the audit are covered by rules or procedures concerning discrimination or harassment allegations of this sort.

The POA said it has used its existing rules on unacceptable behaviour/bringing the union into disrepute both for lay officials who have been given a lifetime ban for ‘behaviour/actions judged to be on the higher scale’ and for staff in breach of the staff handbook. The union adds that training is offered where appropriate.

Usdaw reports that a robust code of conduct is issued to all reps and members attending union events and training courses and is also printed in the final agenda of the union’s annual conference.

Following its 2018 conference, Accord changed its rules to permit the executive council to initiate disciplinary procedures of its own volition without a complaint being received, and also to instigate an investigation when a complaint is received in writing from a member. Although the rules do not make specific reference to discrimination or harassment, there is a clause that expressly states the union actively opposes “all forms of harassment, prejudice and unfair discrimination”.

BFAWU is also currently developing its full policy on this issue but has set up a specific email address that members can use to report discrimination or harassment that goes directly to the general secretary.

To ascertain whether a union truly represents the full diversity of its membership, it needs to monitor the composition of both its members and its various representative structures. This means keeping disaggregated statistics for their membership, in their activist ranks in and their democratic structures.

This section of the audit looks at the number of unions that have disaggregated statistics for their membership and among their stewards/workplace reps, learning reps, health and safety reps, branch officials/officers, equality reps in branches/workplaces, delegates to union conference, delegates to TUC Congress and national executive committee.

Not all unions that collect data are able to state confidently how many of each equality strand there are at a given time because the data often comes from a sample of members or activists rather than the entire membership. This is generally either because not all members have furnished the union with the information, or because the information is collected through application processes devised only after a certain date. We would therefore urge caution when using the figures in this section.

Monitoring membership

The first part of the monitoring section looks at the number of unions that keep statistics on the diversity of their membership, and also gives an idea of how much that diversity ranges across different unions. The variation largely reflects the diversity (or lack of) in the sectors and occupations where unions organise, but also on occasion the geographical location of their membership base.

Many unions that collect data on their membership are unable to provide completely accurate statistics. ASLEF, for example, says the only accurate data it can currently provide is on gender and age. However, a new membership database introduced in 2021 has for the first time options for recording members’ sexual orientation, whether they are disabled and improved categories around ethnicity.

Nevertheless, the majority of unions responding to the audit (35 unions – 85 per cent) do collect data on the number of women in their membership. And 83 per cent (34) of unions provided actual percentage figures, among which the proportion of women in their membership ranged from 6 to 94 per cent.

59 per cent of the unions responding to the audit (24) said they collected data on the number of people from a BME background in their membership, with 54 per cent (22 unions) providing figures. Among these unions, the BME population made up between 0.1 and 40 per cent of their membership.

And 56 per cent (23) of those responding said they monitor the number of disabled members, with 18 unions (44 per cent) providing figures. Among the unions that provided data, the proportion of disabled members varied from 0.1 to 13 per cent.

There has been an increase in the proportion of unions monitoring the LGBT+ identity of their members, to 59 per cent (24 unions), with 19 unions (46 per cent) providing actual figures. Among these unions, the proportion of the membership identifying as LGBT+ varied from 0 to 8 per cent.

61 per cent of unions responding to the audit (25 unions) said they kept statistics on the number of young people in their membership. Unions’ cut-off age for ‘young’ ranges between 24 and 40, though some unions use categories such as ‘trainees’. Nineteen unions (46 per cent of audit respondents) provided figures on young membership, and the proportion ranged from 5 to 38 per cent.

Large unions are rather more likely than medium and small unions to disaggregate membership statistics by demographic (see table 1), though just four out of the six large unions monitor by disability and LGBT+ identity.

Change in the last four years

There has been little improvement in the monitoring of membership by gender, ethnicity or age over the past four years, but there has been a marked increase in the proportion of unions that keep statistics on disabled members and LGBT+ identity. The trends in membership monitoring compared with the 2018 audit are shown in chart 6.

Monitoring and representation of activists

There has been little improvement in the monitoring of membership by gender, ethnicity or age over the past four years, but there has been a marked increase in the proportion of unions that keep statistics on disabled members and LGBT+ identity. The trends in membership monitoring compared with the 2018 audit are shown in chart 6.

Unions were asked if they kept statistics of gender, ethnic background, disability, LGBT+ identity and young age of their reps and activists. On the whole, unions are more likely to keep statistics broken down by gender than by any other equality strand.

Table 2 shows the percentage of responding unions that collect different equality data of various workplace and branch roles.

It shows that, for almost all rep roles, only a minority of unions monitor the different equality characteristics. The exception is that a majority keep gender-disaggregated statistics for stewards/workplace reps (61 per cent) and for health and safety reps (51 per cent). Fewer than one in three know the breakdown by strand of branch/workplace equality reps, other than by gender.

Table 3 shows there is a similar low level of disaggregated monitoring of delegates to union’s own conferences and to TUC Congress. While a majority (59 per cent) have gender-based statistics, a minority of unions do so for any other equality strand on these delegations.

Most unions have some strand breakdowns for their national executive members, most commonly those based on gender (71 per cent).

Comparisons across union size

Small unions are less likely to carry out monitoring than large unions. So, for example, whereas 100 per cent of large unions (six) conduct gender monitoring of stewards and workplace reps, only 57 per cent of medium unions (eight) and 52 per cent of small unions (11) do so. This pattern is repeated for each equality strand.

More or less the same picture – where diversity monitoring is more likely the larger the union size band – is seen for learning reps, health and safety reps, equality reps, branch officials and union conference delegations.

However, monitoring of national executive members and TUC Congress delegations doesn’t fall into a completely uniform pattern. For example, medium unions are slightly more likely than large ones to keep figures on the proportion of BME and LGBT+ national executive members. And small unions are more likely than medium ones to have disaggregated figures for their TUC Congress delegations.

Changes in the last four years

There are some changes in the levels of disaggregated monitoring compared with 2018, though it should be remembered that small changes may be down to the pool and number of unions responding to the audit.

Nevertheless, there appears to have been noticeable changes. There have been increases in the proportion of unions monitoring membership at all levels of activism by LGBT+ status and disability. While monitoring by gender appears to be lower than four years ago in a number of cases, ethnicity monitoring is more widespread for some tiers of activist.

There is also more monitoring by all strands of union conference delegations and national executive committees and by all strands except gender for TUC Congress delegations.

Overall the changes in levels of disaggregated monitoring over the last four years appear to be more positive than were noted in the previous four (2014–2018). However, the gaps in the data demonstrate the need for unions to do more to ensure consistent and accurate monitoring of membership and activists.

What do the figures say about activist diversity?

Unions that kept any disaggregated statistics of activists were asked to provide the figures. Where possible, these figures have been compared with each union’s disaggregated overall membership figures to get an indication of whether women, BME, disabled, LGBT+ and young members are represented proportionately among unions’ ranks of grassroots and senior activists.

Gender: The comparative gender-based statistics show that, on the whole, women members are still underrepresented in these roles in most unions. They are represented proportionately (or more than proportionately) among stewards/workplace reps in just six out of 21 unions; among learning reps in seven out of 16 unions; among health and safety reps in three out of 19 unions; among branch officials/officers in three out of 17 unions; and among equality reps in eight out of 14 unions.

Ethnicity: Fewer unions have figures for activists broken down by ethnicity, but the data that is available indicates that BME members are likely to be underrepresented among stewards, health and safety reps and branch officials. However, BME members are at least proportionately represented among equality reps in 12 out of 12 unions with sufficient data and among learning reps in 10 out of 14 unions with data.

This mirrors research done by the University of Exeter for TUC Education in 2019,8 which showed that women were underrepresented in union rep roles and that BME workplace reps are twice as likely than average to be union learning reps.

Disability: In those unions where sufficient data is available, it is apparent that disabled members are generally well reflected in their activist ranks. They are at least proportionately represented among all roles covered in the audit in the majority of unions, including as equality reps in 11 out of 11 of unions with data.

LGBT+: Where there is sufficient data, it is also evident that LGBT+ members are well reflected among activists. They more likely than not to be at least proportionately represented in each of the roles, including in nine of 10 unions that monitor LGBT+ identity in respect of equality reps.

Young: Of the unions that were able to provide sufficient data on the representation of young workers among workplace/ branch activists, virtually none showed young members being proportionately represented at any level. The most likely area was among equality reps, where three unions had young members fully represented.

Action to increase the diversity of activists

Encouraging more women activists

A number of unions have run campaigns or taken action to increase the number of women in their activist ranks.

For example, the single-employer NGSU attended Employer Equality networks to encourage members from those groups to come forward as union reps, while the EIS ran events on union leadership targeting less-experienced members.

Each Unite region ran a Getting Involved course that aimed to get women members (and non-members) active in the union and to get more experienced reps to increase their involvement and to encourage others. The union also ran online workshops across regions/nations for women, BME and LGBT+ members, which led to more joining their regional equality committee.

The NASUWT ran a Women’s Under-representation Roadshow event in all regions, which increased the number of activists in all roles recorded.

In March 2021 the CWU hosted a CWU Equality Month dedicating a full week for each equality strand (women, BAME, disability and LGBT+). In each week, it hosted webinars, news articles, podcasts and workshops on a broad range of equality subjects, including those promoting and encouraging women, BAME members, disabled members and LGBT+ members into leadership roles.

Encouraging more BME activists

Some unions have carried out a range of actions to get more BME members to participate actively in the union.

One is the NEU, which has organised a number of activities including a Black Lives Matter phone-bank campaign, which identified 40 new workplace reps. It has also rolled out Anti Racist Framework training encouraging take-up of rep roles in the workplace and districts.

The NASUWT has worked on increasing the profile of Black members in leadership positions within the union, which has seen an increase in Black members taking up activists roles such as local secretary, treasurer and equality officer. It has also worked with the TUC Anti-Racism Taskforce on increasing the number of Black workplace health and safety reps.

The RCM has appointed a Race Matters Project Midwife, part of whose role is to increase the number of Black activists. The EIS and NAPO have both established Black members’ networks to encourage further participation. The AUE issued a call for expressions of interest for a Black members’ network.

Encouraging more disabled activists

A number of unions have attempted to further foster disabled members’ participation.

UNISON, for example, took advantage of the move to virtual meetings to ramp up its provision of national training for disabled members interested in becoming disabled members officers in their branch. The union says this is often the first step to activism, with many going on to other roles in the branch and indeed on a regional and national level.

- 8 Stevens H and Graham F (2019). Changing Workplaces: the impact of trade union education on workplace representation. University of Exeter

The NASUWT ran a high-profile campaign demonstrating the impact of Long Covid on disabled teachers, which saw greater interest in disabled members becoming active, particularly as caseworkers, using their direct experiences of overcoming barriers to access at work. The union also increased its profile of Mental Health First Aid activists, which has increased the number of disabled members with mental health specialisms within the union.

The EIS established a disabled members’ network, which increases the members’ participation in the union, while Unite has established a Disability Access Fund to help deaf or disabled members to access branch meetings and other union events and to support innovation and good practice in access for disabled people.

Unions that have taken action to increase the number of LGBT+ activists include UNISON, whose national LGBT+ committee has written a guide on engaging branches in LGBT+ recruitment and organising.

The NEU sees its annual LGBT+ conference as an activist recruitment vehicle so it has a conference guide explaining activist roles and taster workshops on the role of the rep. Separately an LGBT+ inclusion survey with 1,000 member responses generated 280 expressions of interest in becoming a workplace rep. The NEU says the proportion of its workplace reps that are LGBT+ increased by a sixth between 2020 and 2021.

The NASUWT’s annual LGBTI conference includes sessions on getting involved and the benefits of being ‘out’ in the union and being positive role models. This has increased interest among LGBTI members in becoming caseworkers to support members experiencing homophobia, biphobia and transphobia in the workplace.

Encouraging more young activists

A number of unions have been working to improve the representation of young members in their activist ranks.

Unite’s East Midlands region held targeted separate events for women, BAEM, disabled, LGBT+ and young members, which increased these groups’ participation in constitutional committees. It led to two new delegates to the Regional Women’s Committee, one BAEM members becoming an active rep and being invited as an observer to the Regional BAEM Committee meetings. Additionally, eight young members were identified and were invited as observers to the Regional Young Members’ Committee meeting.

In Northern Ireland, Unite Hospitality launched a campaign in 2018 to educate young workers about their rights at work and encouraging them to get in touch for support in organising their workplace. Its key demands include zero tolerance for sexual harassment and safe transport home for late-night workers, and it is also involved in various protest movements in Northern Ireland. In terms of activists this has resulted in increases of 50 per cent for women/non-binary activists, 2 per cent for BAEM activists, 10 per cent for disabled activists, 10 per cent for migrant worker activists and 75 per cent for young activists.

Equality officers and reps

Full-time equality officers can play an important role in leading on equality and ensuring it stays on the union’s agenda. Some unions approach this with an officer for overall equality, while others have officers responsible for one or more strands. Some unions have both.

The audit shows that 18 unions (44 per cent) have at least one officer at national level whose sole responsibility is either for overall equality or for a single strand. Five of these also have additional officers with partial responsibility for equality.

A further 15 unions (37 per cent) do not have dedicated equality officers, but have officers at national level for whom equality (either overall or for individual strands) is part of their explicit responsibility.

The most likely type of dedicated equality officer is for overall equality, employed by 17 unions. Five unions employ dedicated equality officers for women, three do so for BME members, three do so for disabled member, three do so for LGBT+ members and four do so for young members. (Some unions have more than one dedicated equality officer).

Some unions are too small to employ dedicated equality officers, while others nominate or elect lay members, such as specific national executive members to take on the role of leading on equality issues.

Some changes since the 2018 audit include the PFA’s development of its equality, diversity and inclusion team to include a dedicated Women’s Football Executive and officer working to develop and support South Asian inclusion in English football. The CWU has also changed its equality structure (see box).

Equality reps at workplace or branch level

Equality reps in the workplace or branch are there to raise awareness of equality-related concerns, help ensure that equality is properly considered as part of all workplace consultation and bargaining activities and support members who feel isolated or face discrimination. These are most frequently responsible for all strands, though some unions have equality reps for specific strands.

Twenty of the unions responding to the audit (49 per cent) have a rule or practice on workplace or branch reps for overall equality, six (15 per cent) have them for women’s equality, eight (20 per cent) have them for BME members, four (10 per cent) for disabled members, five (12 per cent) for LGBT+ members and six (15 per cent) for young members.

The system of local equality reps is much more likely to be found in large unions (83 per cent have equality reps) than in medium (50 per cent) or small ones (38 per cent). The pattern is the same for equality reps for individual strands.

In total, 85 per cent of members of unions who responded were in unions with a rule or practice on overall equality reps.

Since the last audit, UNISON has adopted a rule change that says that all branches should have a women’s officer, who must be a woman.

And a number of unions have made efforts to expand their equality rep ranks. The FDA has run equality rep training and developed a handbook. Napo, which has a role of anti-racism officer, has worked with the employer to secure a day-a-week facility time for each officer to support the work of the employer’s Race Action Programme.

Equality committees and networks

This section examines the presence of both formal lay structures for equality or individual strands and also informal networks.

The main questionnaire asked about these separately. It showed that 18 of the 37 unions completing the main questionnaire (49 per cent) have formal bodies or committees for overall equality, 13 (35 per cent) do for women, 15 (41 per cent) have formal bodies for BME members, 12 (32 per cent) for disabled members, 14 (38 per cent) for LGBT+ members and 14 (38 per cent) for young members.

The proportion of unions with formal bodies for each of the strands has declined since 2018.

One contributor to this fall is changes in the equality structure of the CWU. It replaced its national advisory committees for women, BAME, disability and LGBT+ categories with its new structure for equality, including equality seats on its NEC (with full voting rights) plus regional and branch equality leads (see page 27), which hold regular meetings with spaces for the separate equality strands.

On the other hand, the WGGB has established a formal equality and diversity committee and the UCU has added an equality standing committee for migrant workers, with the same status as its committees for Black, LGBT+, women’s and disabled members.

A big change in this area in recent years has been the growth of informal networks and groups in unions, either for overall equality or for particular groups of members. In some cases, these groups and networks arise spontaneously from members and in others they are initiated by officers or other structures of the union.

Looking at the unions completing the main questionnaire, it is evident that there has been a further growth in their popularity since 2018. Apart from informal networks for overall equality and for women, which have declined, the proportion of unions with such groups for the other strands has increased. This is especially true in relation to informal groups for BME members, which now exist in 54 per cent of unions compared with 37 per cent in 2018.

Indeed, the most common type of group is for BME members, which exist in 20 of the 37 unions completing the main questionnaire (54 per cent). Sixteen of those unions (43 per cent) have groups for disabled members and the same number for LGBT+ members. Fifteen (41 per cent) have groups for women members, 11 (30 per cent) have them for young members and six (16 per cent) have them for overall equality.

In addition, among the four unions completing the abbreviated version of the questionnaire, two have informal overall equality groups while one does so for each of the single strand groups.

Overall, 30 of the 41 unions responding to the audit (including those using the abbreviated questionnaire) (73 per cent) have at least one informal equality group or network.

Other informal groups linked to equality include the NUJ’s 60+ council, which now has its own newsletter, while Equity has a network focused on social class that intersects with the union’s other committees and networks. It also has a network for Gypsy, Romani and Traveller members and one for members who are non-UK nationals. NSEAD has an anti-racist education action group and an anti-disablist special interest group steering its work.

There has been considerable development in this area since the last audit. For example, the GMB established national networks of regional women, Black, disabled and LGBT+ activists in 2020, and in 2021 BFAWU established informal networks for women and Black members. In early 2022, it launched a young members’ network.

The NAHT has developed three networks since 2020, starting with its Leaders for Race Equality network, which began in response to the Black Lives Matter campaign. The development of this network led to the request from members to form the LGBT+ network, which started in January 2021 and “grew exponentially within a few months”, according to the union. The NAHT now also has a network for disabled members, the first meeting of which was scheduled for early 2022.

While Napo’s networks for women and Black members have been around for a long time, more recently it has set up networks for LGBT+ and disabled members and has relaunched one called Napo – The Next Generation.

However, launching networks is not always straightforward, some unions have found, and interest can wax and wane. The AUE has called for expressions of interest each year but not had a big take up, so building the networks is still in progress. And the SoR recently split its single equality network into individual workstreams. However, no member interest was received for the young or women’s groups, which are consequently on hold, although a ‘students’ network is still in operation.

Informal networks are not necessarily replacements for formal committees, and to some extent they perform slightly different roles. Equity, for example, encourages informal networks of members allied to formal committees and the POA is setting up networks in parallel with its four equality committees “to engage with ordinary members as well”. On the other hand, ASLEF’s disabled members’ committee did not have formal status when it was established in 2020 but since then has become part of the union’s rulebook. And in the UCU, an informal network for disabled members was established by the chair of the Disabled Members’ Standing Committee during the pandemic to foster discussion of the challenges linked to pandemic health and safety.

21 of the 37 unions completing the main questionnaire (57 per cent) have both formal and informal equality groups of one type or another. The group comprises five large unions, nine medium unions and seven small unions.

Equality conferences and seminars

Unions were asked if they held regular national conferences or seminars either for overall equality or for specific strands of members. Eight unions (20 per cent) hold national conferences or seminars for overall equality, while 10 (24 per cent) hold them for women, 13 (32 per cent) for BME members, 10 (24 per cent) for disabled members, 12 (29 per cent) for LGBT+ members and eight (20 per cent) for young members.

There has been a fall in the proportion of unions holding national conferences for overall equality, women and disabled and young members since 2018, when there had already been a decline in conferences over the previous four years (see chart 8). However, the proportion of unions holding national conferences or seminars for BME members has increased, and the number holding LGBT+ events stayed at the same level.

Holding national conferences of this sort has almost become the preserve of large unions. All of the six large unions hold them for BME and LGBT+ members and five do so for both disabled and young members, though only four do so for women and two for overall equality.

Nevertheless small numbers of other unions do still hold national equality events. Conferences for overall equality, women and LGBT+ members are each held by four medium unions (29 per cent) and two (10 per cent) small unions. Four medium unions and three small unions hold them for BME members.

The CWU’s rules in this area have changed since the last audit such that its equality strand conferences were replaced with a full day of equality business every two years at its general conference and, in the intervening year, a national two-day equality event with breakout sessions for separate equality strands groups.

Nautilus has widened its Equality and Diversity Forum (EDF) since the last audit to give more strands than previously the opportunity to have their own ‘safe space’ meeting alongside the main EDF. Previously this was available only to the women’s and youth groups.

The GMB has established annual national summits for women, Black members, LGBT+ members and disabled members in the last four years. Unite has held a national online equality reps conference in 2021

And the UCU has established an annual conference for migrant members, on the same footing as the existing ones for Black, disabled, LGBT+ and women members.

Of the 37 unions completing the main questionnaire, 16 (43 per cent) hold conferences or seminars on overall equality at regional level.9

A small number of unions held regional events for individual equality strands: 27 per cent of unions held conferences for women; 32 per cent for BME members; 27 per cent for disabled members; 32 per cent for LGBT+ members; and 19 per cent for young members.

These figures are higher than they were in 2018, except for women and young members, suggesting that some unions may be switching from national to regional gatherings of this sort.

TUC Congress monitoring

At the 2021 TUC Congress (held online due to Covid-19), equality monitoring of delegates was carried out. Any comparisons are to 2019 as the 2020 TUC Congress did not have delegates due to the pandemic.

All 468 delegates completed the monitoring form, though delegates were able to select ‘no answer’ or ‘prefer not to say’ for questions. The TUC has seen an increase in the number of delegates completing monitoring forms since moving to an online form as part of the registration process.

TUC data showed that 52 per cent of delegates were women, compared to 43 per cent in 2019. 57.6 per cent of delegate speakers were women, which is the highest for any Congress. However, given that Congress was online, and there were fewer speakers than usual, it is difficult to make comparisons to previous years.

In 2021, 12.6 per cent of delegates identified as BME compared to 10 per cent in 2019, which was a dip from 12.4 per cent in 2018 and 15 per cent in 2017.

19 per cent of delegates identified as disabled, up from 16 per cent in 2019, and 10 per cent of delegates identified as LGB, again an increase from 7.9 per cent in 2019. 0.5 per cent of delegates identified as having a different gender identity to that assigned at birth. This was down from 1.9 per cent in 2019.

The proportion of delegates under 35 was effectively unchanged (7.5 per cent in comparison to 7.4 per cent in 2019).

Reserved seats

Some unions have rules on reserving or guaranteeing seats on elected union structures and delegations to ensure a certain level of representation for groups that have traditionally been underrepresented.

All unions responding to the survey were asked about reserved seats on national executives, conference delegations and TUC Congress delegations (see chart 9).

- 9 This question was not asked of those completing the abbreviated questionnaire.

The large unions are more likely than medium and small unions to have reserved seats on these bodies and delegations, especially with regard to TUC Congress delegations, where there is a TUC rule in place to foster this.

There have been substantial developments in the area of reserved seats on unions’ national executive bodies since the last audit. Currently, 34 per cent of unions have reserved seats for BME members on their executive bodies, 29 per cent of unions have them for women, 27 per cent for disabled members, 22 per cent for young members and 20 per cent for LGBT+ members.

These figures are all higher than four years ago, especially for disabled, LGBT+ and young members (see chart 10).

Some of the key developments in this area since the last audit included rule changes in the GMB, which has brought in reserved seats for all five strands on its CEC, while the CWU now has guaranteed seats for women, BAME, disability and LGBT+ lay members on its National Executive Committee (NEC).

PCS, which previously had reserved seats for Black members on its NEC, has now added them for young, disabled and LGBT+ members. And the UCU, which already had them for Black, women, LGBT+ and disabled members, has added reserved seats for migrant members.

The CSP, which has a Council rather than a National Executive, has introduced two reserved seats for Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic members, as they were not previously represented on the Council.

While not directly an equality strand, the AEP has brought in reserved seats for trainee and newly qualified members in the last four years.

There have also been some developments in terms of reserved seats on other bodies and delegations.

In 2020 the MU introduced a reserved seat structure on all of its industrial committees to improve representation. It held events with the EDI member networks to encourage more diverse members to stand for nomination, explain the role of a committee member and discuss standing for committees and the election process.

A UCU rule change means its five equality standing committees now have the right to send two voting delegates (as opposed to observers) to UCU Congress, while the EIS now reserves two places for LGBT and BAME activists for its delegation to the Scottish Trade Union Congress. And Unite has introduced rules giving places at its Policy Conference to representatives from the national women’s, BAME, LGBT+ and disabled members committees and additionally ensuring that the delegations from its regional committees to the conference include women and LGBT+, disabled and young members.

The main way in which unions provide services specifically aimed at particular strands of members is through websites. Just under half of unions responding provide website services in each case for women, for BME members, for disabled members and for LGBT+ members. Just 22 per cent provide web services specifically for age-related groups.

Unions were asked if they monitor their general service provision (excluding trade union training – see page 36) to see if it delivers equality of access. Overall, 44 per cent of unions do so, including five large unions (83 per cent), six medium unions (43 per cent) and seven small unions (33 per cent).

An important equality-related service provided by unions is taking discrimination cases to tribunal. All unions were asked if they monitor the number of cases they take to tribunal under each of the discrimination jurisdictions.

Around half of unions said they monitor the cases taken to tribunal, rather more than in 2018. Slightly higher proportions monitored race and pregnancy and maternity discrimination cases (56 per cent in each case) than for other protected characteristics: sex (51 per cent), disability (54 per cent), sexual orientation (51 per cent), religion/belief (46 per cent), gender reassignment (49 per cent), age (51 per cent) and marriage and civil partnership (41 per cent).

In terms of what the monitoring shows, the GMB reported that the abolition of tribunal fees in 2017 has led to a marked increase in claimants wishing to pursue employment tribunal claims over the past four years, particularly in relation to discrimination claims as these fell into the higher fee bracket.

Its figures for discrimination cases between 2020 and 2021 reveal a big increase under all jurisdictions except marriage and civil partnership, and particularly for disability, where the number rose from 103 to 165 in that period.

The GMB ascribed some of the rise in disability discrimination cases to the impacts of the pandemic, often around reasonable adjustments, health and safety concerns related to those at higher risk of Covid-19 and mental distress caused by the pandemic.

It also reported a rise in equal pay claims, which it says arose partly because of gender pay gap legislation, as well as high-profile equal pay decisions against supermarkets and in the case of Samira Ahmed against the BBC.

The GMB also said that, since the heavier publicity around the Black Lives Matter campaigns of mid-2020, it has seen an increase in members wishing to pursue race discrimination claims.

Prospect and the NUJ also reported an increase in race discrimination claims over the past four years, the NUJ referring particularly to pandemic-related dismissal claims on the part of protected groups and claims over Long Covid.

The CWU and Usdaw referred to changes in tribunal processes since the last audit, including the shift to online applications and tribunal hearings conducted by video or telephone conference. Usdaw reported that this has meant problems with unreliable internet connections and not being able to conduct hearings in person. The union also notes “the significant increase in time before hearings are being listed which leads claimants to have to wait too long for justice and appropriate compensation”.

Three-quarters of unions responding to the main questionnaire provide their paid officials with education or training in taking discrimination cases, while two-thirds provide it to lay representatives.

Trade union training

Around a third of unions take steps to encourage participation in education and training courses by members of the equality groups. 34 per cent do so to encourage women, 37 per cent to encourage BME members, 32 per cent for disabled members and 32 per cent for LGBT+ members. However, only 22 per cent have acted to ensure age diversity. These figures are virtually unchanged since 2018.

Many unions do this by promoting training courses through their equality groups. The SoR does this, as well as through its student groups, and these groups also help the union to explore ways to improve accessibility. The union has recently employed a learning technologist to assist with this work.

Other examples include the NEU, which provides accessible venues for in-person courses, a transcription service for digital courses and BSL upon request, while Unite advertises that it provides a childcare allowance, crèche provision and support for carers/personal assistants at its national women’s week course.

A new question for the 2022 audit asked about the use and equality impact of online courses. Three quarters of unions (31) have increased their online education or training offer to members in the last four years, including during the pandemic. This included all six large unions, 86 per cent of medium unions and 62 per cent of small unions.

Some of them noted a change in the diversity of course participants as a result. Among those, the most common comment was that more women had participated in online training, while two noted more disabled people taking part and the CWU said participation by young members as well as by women had increased. The EIS reported that it now has “an active BAME network, and disabled members who had previously been reluctant to be further engaged in union activity [who] … meet virtually to work on various projects, as well as a new national disabled members network that involves participants from remote highland and island communities”.

Unions completing the main questionnaire were asked if they conduct monitoring of attendance by particular groups at union courses. This occurs in only a minority of unions and the proportions of unions who conduct monitoring are lower than in 2018 for every strand.

Campaigns and communications

There is an increasing awareness that unions must consider diverse audiences in their campaigns and communications. Most of the unions completing the main questionnaire (82 per cent) say they take some action to ensure that their materials indicate a diverse membership or audience and that language is accessible and does not cause offence to particular groups.

A smaller proportion (45 per cent) help or encourage their branches to take these issues into account in their materials. The EIS facilitated the production of locally produced campaign materials in Polish and Hindi and NASUWT in 2019 provided its local associations/branches with guidance for hosting meetings and events to ensure they are inclusive and avoid barriers to participation from specific groups based on gender, ethnicity, disability access and faith.

61 per cent of all unions participating in the audit take some measures to ensure materials are accessible to people with visual or hearing impairments; 49 per cent provide materials in different languages where appropriate; and 29 per cent monitor the impact of campaigns on the diversity of their memberships.

Technology has afforded more opportunities to ensure information is accessible by a wider variety of groups in recent years. Several unions referred to ensuring their accessibility options reach the latest standards for their websites and other online offerings.

UNISON has undertaken an accessibility audit of its website to ensure that all of its campaign pages are fully accessible, with its Covid-19 pages the first to be so, and Unite has added sophisticated accessibility tools to its website (see box).

For some years many unions have been providing materials in other languages, and the GMB has now added a translation tool to its website.

In a sign that unions’ equality agendas are becoming increasingly sophisticated, just over half (54 per cent) have launched campaigns or policy initiatives in the last four years that have consciously sought to link two or more equality strands. In 2018, 42 per cent of unions had done this.

For example, the NASUWT’s ongoing anti-racism campaign and strategy has addressed the intersection of racism and other forms of oppression such as sexism, misogynoir (prejudice against Black women) and ostracism on the grounds of faith and religious belief. In addition, its sexual harassment campaign specifically addresses intersectional types of harassment such as those that affect Black women, LBT women and young and disabled women.

Usdaw took new steps in its longstanding national mental health campaign after a survey of members’ experiences of working through the pandemic showed that the mental health of young workers was being particularly badly affected. The campaign group worked with the National Young Workers’ Committee and the National Equalities Advisory Group to run an awareness-raising campaign.

Unions were asked if they had an equal opportunities or non-discrimination policy relating to their own employees – either general or referencing specific strands of staff.

Overall, 37 unions (90 per cent) did, compared to 33 unions (87 per cent) in 2018. The total included 100 per cent of the large unions, 86 per cent of medium unions and 90 per cent of small unions. For small unions, this is an increase on the 80 per cent recorded as having a policy in 2018. Thirty-six unions had a procedure for complaints related to breaches of their equality or non-discrimination policy.

Thirty-four unions (83 per cent) had an explicit reference to dealing with harassment/discrimination within their internal complaints, disciplinary or grievance procedures. This included 100 per cent of large unions responding to the audit, 79 per cent of medium ones and 81 per cent of small ones. For medium unions this is a decrease from 2018, while for small ones it is an increase.

The NASUWT says it deals with all complaints of harassment as misconduct issues. After consultation with women and Black staff members the union has reviewed and updated its complaints procedures to ensure that the investigation process is more robust. The BDA’s equalities and disciplinary and grievance procedures specifically reference examples of harassment/discrimination and how they will be dealt with, while Usdaw lists examples of potential gross misconduct in its Disciplinary Rules and Bullying and Harassment procedures, and also mentions harassment in its grievance procedure.

Some unions added that they had a specific policy on bullying and harassment or dignity at work or are currently developing one.

Fourteen unions said they had done specific work in the last four years in their efforts to prevent sexual harassment of staff, including training staff and establishing new policies and procedures.

The PFA, for example, has developed a consent training programme with information on sexual consent and personal integrity, while the FBU has established a working party to review processes following the publication of the Monaghan report into sexual harassment in the GMB. UNISON has trained staff to investigate incidents and to act as confidential advisers. Both Nautilus and BFAWU have conducted surveys, after which BFAWU established an organisational policy.

ASLEF has formed a special working group on sexual harassment, looking at the issue from a members’ and staff perspective. The group has developed a mutual respect statement and a sexual harassment procedure.

The NEU ran sexual harassment training for members of the senior management team in early 2021, delivered by a TUC-endorsed facilitator, with similar training rolled out to all managers later in the year. Sexual harassment training is now mandatory for all new line managers and forms part of the NEU’s annual staff training plan. The union also updated and reviewed its Equality and Diversity and Dignity at Work policies in consultation with staff unions and are running briefing sessions for all staff.

The NASUWT has adopted a range of measures since the 2018 Equality Audit. A Tackling Sexual Harassment and Misogyny Action Plan, approved by its national executive in 2020, includes processes for dealing with sexual harassment complaints from staff. The union has set up a reporting mechanism via a dedicated and confidential staff email account for reporting sexual harassment incidences and related issues. Zero tolerance on harassment posters are displayed throughout every office building. The union also has a new Equality, Diversity and Inclusion policy, which includes tackling sexual harassment, and a new women’s staff forum has been established.

Unions have provided a range of new types of training for staff in the last four years, with popular topics being unconscious bias, mental health awareness and anti-racism. Specific relatively new subjects run by individual unions have included understanding anti-Semitism, allyship, understanding sexuality, neurodiversity, equality impact assessments and responding to sexual harassment disclosures.

Staff pay and conditions

Unions were asked if staff pay and conditions have been reviewed in the last four years to ensure they do not discriminate against any groups. Thirteen (32 per cent) have done so to ensure pay and conditions don’t discriminate on grounds of sex, 12 (29 per cent) have checked on grounds or race, nine (22 per cent) on grounds of disability, eight (20 per cent) on grounds of LGBT+ status and 10 (24 per cent) on grounds of age.

The six large unions are the only ones legally required to report on their staff gender pay gap but a further five unions (three medium and two small) do so voluntarily. In addition, three unions report their ethnicity pay gaps and one its disability pay gap.

Thirty-seven unions (90 per cent) reported that all their staff were able to work more flexibly during the pandemic than beforehand, while another two said it had applied to some of their staff. However, just 29 unions (71 per cent) planned to have greater work flexibility post-pandemic than before it, with another six (15 per cent) saying this had not yet been decided.

Monitoring of staff diversity

As chart 11 shows, just 63 per cent of unions have statistical records of the number of staff who are women – a smaller proportion than did so four years previously. The latest figure includes 83 per cent of large unions, 64 per cent of medium unions and 57 per cent of small unions.

Just half of unions (51 per cent) have records of BME staff, compared with 55 per cent in 2018, while only 34 per cent do so for disabled staff, down from 45 per cent four years ago. 34 per cent have records for LGBT+ staff, the same as in 2018, while there is slightly better news in relation to records for age, now kept by 51 per cent, up from 45 per cent. In all cases the likelihood of a union keeping these statistics is lower the smaller the size band of the union.

This fall in diversity monitoring follows a decline already seen in the period 2014–2018.

Union equality audits

Thirteen unions (32 per cent) said they had carried out their own equality audit since the TUC commenced conducting equality audits in 2003. These were four large unions (67 per cent), six medium unions (43 per cent) and three small unions (14 per cent). Together they account for 72 per cent of members covered by all unions participating in this TUC audit.

UNISON makes an equality impact assessment of its activities called Equal Means Equality – Making It Happen. It has included audits of membership participation, tribunal cases, staff and training courses and opportunities. This has resulted in the implementation of a range of membership and staff training courses in leadership and management. The plan is measured using project management principles and tools to assess how key objectives are delivered in relation to the outcomes set out in the plan.

CWU has improved the way it collects data and made improvements to its central data systems, which makes it easier for branches to update their activism data. It includes a proportionality dashboard that provides monthly updates to CWU regions, affording regions and regional equality leads opportunities to target areas where improvement is needed.

The RMT brought together the membership data that it had provided to TUC Equality Audits over the years and published an equality audit of its own to assess its membership in terms of the equality groups.

Equality action plans

Twenty-two unions (54 per cent) said they have an equality action plan in place. These included four of the large unions (67 per cent), seven medium unions (50 per cent) and 11 small unions (52 per cent). Together they account for 73 per cent of members covered by all unions responding to this audit.

The NASUWT completes an audit every two years, in conjunction with the TUC, and sets an action plan thereafter. Utilising its ‘strategic equalities framework’, the union identified a series of targeted commitments and actions to drive forward equalities work across the union. These focused on: leadership; policy and strategy; people; resources; processes; staff needs; members’ needs; impact beyond the union; and review of results. These priorities have also been incorporated into a strategic organising plan adopted by its national executive in 2021.

A number of unions have a process similar to that of ASLEF, whose plan is reviewed by its equality committees and equality adviser, with reporting to the union’s executive. The AEP’s plan, priorities and future recommendations are reported to the NEC.

Prospect has a three-year equality, diversity and inclusion plan alongside its customer relations management plan, with points built in to monitor progress. And the MU has published its plan on its website10 showing targets and deadlines in place for measurable areas.

- 10 musiciansunion.org.uk/about-the-mu/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/equality-action-plan

Since 2003 the TUC Equality Audit has provided a yardstick to measure how the trade union movement is promoting equality for all and working to eliminate all forms of harassment, prejudice and unfair discrimination, both within its own structures and through all its activities. This audit has highlighted the progress that has been made since 2018 and examples of the work unions are doing that can be used as best practice for others.

From the analysis of the results, the key areas for action for the movement are first to improve the quality and consistency of monitoring of union members and activists. Monitoring is the first step to identifying whether those from equality groups are active in our structures; from here we can establish why and tackle any barriers to involvement. The audit shows that we cannot be confident in the data we do hold and the need to do more to improve this.

As trade unionists we know representation is not enough, so the second area of action is to ensure that equality groups have voice within our movement via elected positions, for example workplace representatives, reserved seats and structures such as equality conferences. The audit shows a mixed picture, with improvements in some areas such as the number of unions with reserved equality seats but less progress in others, for example a decline in national equality conferences.

Finally, for the first time affiliates were asked if they had done any specific work to prevent sexual harassment of their staff in the last four years alongside other questions on bullying and harassment across their structures. The audit highlights the need for us to do more as a movement to build preventative cultures and tackle sexual harassment.

There have been no union mergers since the last equivalent TUC Equality Audit (2018) that substantially affect this analysis, although Usdaw and Prospect have absorbed NACO and SUWBBS respectively, neither of which participated in 2018. However, this audit includes two respondent unions – NHBCSA and NSEAD – which were not affiliated to the TUC in 2017–18.

Data analysis

The percentages of unions quoted in this report are generally of the total number of unions responding to the audit. In some cases, analysis has also been carried out according to union size. The aim of this approach is to acknowledge that certain rules and structures may be more likely to be adopted by unions of different sizes.

For such analysis, the unions responding have been grouped into three size bands corresponding to the TUC rules on the composition of the General Council.11 In this report they are described as either ‘large’ (section A unions), ‘ medium’ (section B unions) or ‘ small’ (section C unions).

The large unions that responded to the audit are as follows:

- 11 “Section A shall consist of members from those organisations with a full numerical membership of 200,000 or more members. Each such organisation shall be entitled to nominate one or more of its members to be a member or members of the General Council and the number of members to which the organisations comprising Section A shall be determined by their full numerical membership on the basis of one per 200,000 members or part thereof provided that where the total number of women members of any organisation in Section A is 100,000 or more that organisation shall nominate at least one woman.