Women and Equalities Committee consultation on the rights of older people

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) exists to make the working world a better place for everyone. We bring together around 5.5 million working people who make up our 48 member unions. We support unions to grow and thrive, and we stand up for everyone who works for a living.

We appreciate the opportunity to respond to the Women and Equalities Committee consultation on the rights of older people. Our consultation focusses on two questions – digital exclusion for older people, and what more needs to be done to support older people who want to stay in work longer.

Question 1: What steps are required to prevent older people from being digitally excluded; and in what areas is digital exclusion of older people a particular concern?

Older people face a higher risk of digital exclusion. Age UK estimates that one in five people aged 65 or over does not use the internet, with this figure rising to one in three people aged 75 and above.1 Increasingly, those unable to access the internet easily face barriers to fully participating in society and accessing vital services.

We believe this growing digital divide has a harmful impact on older people in many ways, including accessing the social security systems and healthcare systems. But this response will focus on an area of particular concern to several TUC-affiliated unions: financial services.

Unions representing workers in the financial sector have raised concerns about the impact of the closure of high street bank branches on people who are digitally excluded or ‘e-disadvantaged’. 2 The number of branches in the UK fell by 40 per cent from the start of 2015 to the end of 2021, from 9,375 to 5,653.3 This rapid decline has left those who rely on branches, which includes a disproportionately high number of older people, at risk of being unable to manage their money.

According to the FCA, one in six people aged 65-74 (17%), and one in three aged 75 or over (33%) do not use online or mobile banking services.4 The proportion of over 75s who had not done so over the 12 months up to May 2022 was the highest of any segment of society looked at by the FCA. Older people were correspondingly more likely than other age groups to depend on bank branches. More than one in four people aged 65 to 74 (27%) and one in three aged 75 or over (35%) used one regularly. The only group surveyed that was more likely to depend on in-branch services were those with a household income below £15,000 a year. Older people who are working class or on low incomes are particularly likely to face digital exclusion, with Age UK research finding less than half of older people in C2DE social grades (49%) were comfortable with online banking, compared to 72% of those in ABC1 social grades.

There is also evidence of a gender divide in the ability of older people to access online banking, with research from Age UK finding women significantly more likely than men to say they are uncomfortable with the idea of banking online (36% vs 24%).5

Age UK’s research identified fear of fraud, a lack of confidence in online banking, and a lack of IT skills as the main barriers to access. The TUC believes, therefore, that it is vital to both maintain access to face-to-face banking services, and to provide greater support for older people to access online services.

We support the creation of banking hubs, where customers of a range of banks can deposit and withdraw money, and access a range of banking services at a single location. The roll-out of these services, which has been discussed since the early 2010s has been slow, with just 24 currently in operation around the country, at a time when many small towns no longer have any high street bank branches remaining. This programme should be accelerated, with the aim of ensuring that banking hubs are open where they are needed before the last branch on a high street is closed.

Trade unions also believe that banks should be providing more support to customers with low levels of computer literacy or of experience using online banking. This could be assured by putting agreements in place to transfer current workers whose jobs are threatened by automation or digitalisation to roles providing face-to-face or phone support for people to use online services.

We also believe that the Post Office network has a valuable role to play in giving in-person access to financial services, particularly in rural areas where it may be more difficult to set up banking hubs. Post Offices already play an important role for many people, with one in five using one weekly, and almost half the population visiting a branch monthly and on in five customers using a branch to withdraw or deposit cash. 6 Older people and rural residents are the most likely to use a post office regularly. 7

This reliance on Post Office branches means it is important to stop the decline of the network. Although the number of branches has remained stable since 2010, declines before this, and the growing number of temporary closures and outreach branches, which open limited hours,8 has made it more difficult for many to access branches. We also support the expansion of banking services that can be provided by the Post Office. A 2017 report

commissioned by the Communication Workers Union makes the case for establishing a Post Bank, along the model followed in France or Italy. 9 As well as advancing financial inclusion by giving more people access to in-person services, this model could improve access to finance and banking services to small businesses. This not only has the potential to boost local economies, but could also make it easier for small businesses to continue accepting cash, slowing down the move to a cashless society, which threatens to exclude older and lower income customers, who are more likely to rely on cash transactions.

TUC Policy recommendations

- Accelerate the establishment of banking hubs, to provide access to face-to-face banking in areas with no or few single bank branches.

- Increase the support offered by banks over the phone or in person to help customers with limited experience of online banking to use these services by redeploying staff whose jobs are threatened by technological changes.

- Preserve the Post Office network and increase the range of banking services available through it by the establishment of a Post Bank

- Question 5: Labour market access- What more needs to be done to support older people who want to stay in work longer?

The proportion of people in work in the UK has not returned to pre-covid levels. Between January to March 2020 and October to December 2023 the employment rate for people aged 16-64 dropped from 76.3 per cent to 75.8 per cent. While the UK was not alone in seeing the numbers in work decline during the Covid-19 pandemic, it is unique among OECD countries in not seeing numbers bounce back to pre-pandemic levels..10

Inactivity during this period rose sharply, though this has been falling more recently due to falling student numbers. However, the number of people who were economically inactive because of long-term sickness is significantly higher, rising from 2.1 million in the first quarter of 2020 to 2.6 million at the end of 2023.

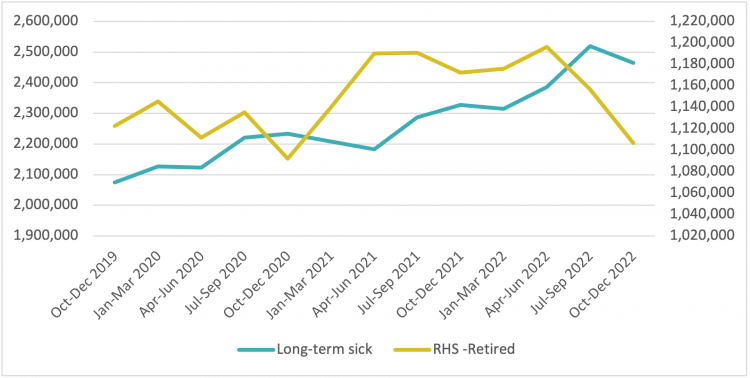

The large increase in the numbers of older people leaving the labour market before they reach state pension age initially led to discussion of a ‘great retirement’. The suggestion that older people were deciding to leave work early having re-evaluated their lives over the pandemic. But the data is clear that the real story is that a growing number of people are simply too sick to work. While the number of people below state pension age who are retired has dropped below levels seen before the pandemic, the number who are out of work because of long-term ill health is 500,000 higher.

Our report last year 11 on the growing economic inactivity among older people, revealed that the increase in poor health was seen across all age groups but was greatest among older people, who were already more likely to be out of work because of ill health. The result was 1.5 million men and women between 50 and state pension age out of work because of long-term sickness.

Our analysis in this consultation is mainly from our labour market report last year, in general we refer to older workers as aged between 50-65 and the analysis is from 2019-22. The report clearly shows recent trends in the labour market for this age group.

Health

There was a surge in the number of people aged 16-64 who were retired in the first half of 2021 (see chart 1). But this was followed by an equally strong decline in the second half of 2022, with the number of people in this age group who had retired from paid work falling below the level it was before the pandemic (1.1 million). The latest available data in 2023 shows it is still at 1.1 million.

Chart 1: Number of people age 16-64 economically inactive because of retirement and long-term sickness, Q3 2019 to Q4 2022

- 1 https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/active-communities/policy-briefing---facts-and-figures-about-digital-inclusion-and-older-people.pdf

- 2 https://congress.tuc.org.uk/motion-29-financial-services-supporting-the-e-disadvantaged/

- 3 https://rgs-ibg.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tran.12656

- 4 https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/financial-lives/fls-2022-retail-banking-savings-payments.pdf

- 5 https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/money-matters/the-impact-of-the-rise-of-online-banking-on-older-people-may-2023.pdf

- 6 https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/policy/publications/gaps-in-the-network-impact-of-outreaches-and-temporary-closures-on-post-office-access/

- 7 https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/campaigns/Post/Consumer%20Use%20of%20Post%20Offices%20Summary%20Report.pdf

- 8 https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/policy/publications/gaps-in-the-network-impact-of-outreaches-and-temporary-closures-on-post-office-access/

- 9 https://www.cwu.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/FINAL-REPORT-070917-Making-the-case-for-a-Post-Bank.pdf

- 10 Financial Times, Chronic illness makes UK workforce the sickest in developed world, July 2022 - https://www.ft.com/content/c333a6d8-0a56-488c-aeb8-eeb1c05a34d2

- 11 TUC, 2023 - https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/creating-healthy-labou…

By contrast, the number of people who were economically inactive because of poor health, was significantly higher than it was going into the pandemic, rising from 2.1 million in the first quarter of 2020 to 2.5 million in the fourth quarter of 2022, and continued to rise in 2023.

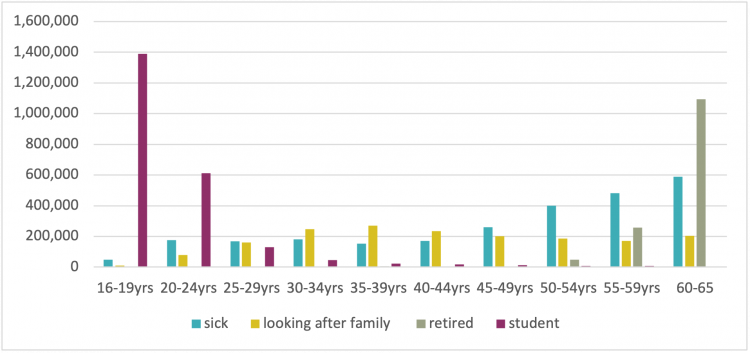

Older people are the most likely to be out of work because of long-term health conditions, with the numbers rising steadily once people reach their 40s (see chart 2). The number out of the labour market because of caring responsibilities was at its highest among people in their late 30s at 270,000, but there was considerably less variation in this figure across different ages, with more than 200,000 people aged 60-65 economically inactive because of caring responsibilities. While retirement becomes a factor in people’s 50s, the increase in ill health is far more significant. Our analysis showed in total there were just over 880,000 people aged 50-59 who are too ill to work, and 300,000 who class themselves as retired.

Chart 2: Number of people economically inactive by age and reason for inactivity, Q3 2022

The rise in inactivity related to sickness from 2019-22 was also fastest among older age groups, with an increase of more than 250,000 among people aged 50-65 over the period (see chart 3). This increase in poor health among this age group was mostly linked to physical conditions, with rises in the number of people unable to work because of conditions affecting feet and legs, back and neck, and chest or breathing issues, and there was also an increase in the numbers unable to work because of conditions linked to depression.

Chart 3: Change in number of people economically inactive by age and reason for inactivity, Q3 2019-Q3 2022

Occupation

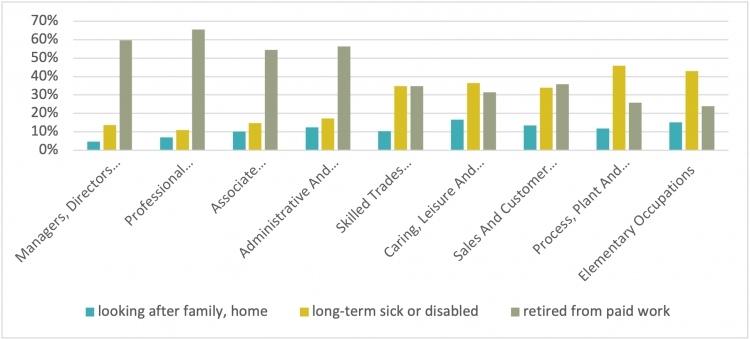

One of the most significant factors affecting whether someone is likely to be forced out of the labour market by ill health is the kind of work they do. People who are economically inactive because of long-term health conditions who have previously been in work are more likely to come from low paid occupations such as cleaning, caring, and retail work, or from physically demanding occupations such working with heavy machinery or in skilled trades. Economically inactive people who previously worked in senior management positions or the professions are much more likely to have retired from paid work than to have been forced out by either ill health or caring responsibilities.

The occupational groups with the highest proportion of inactivity due to ill-health among the economically inactive are ‘process, plant and machine operatives’ (46 per cent) and ‘elementary occupations’ (43 per cent) which includes jobs such as cleaners and security guards (see chart 4). The other occupational groups with higher-than-average levels of inactivity due to poor health are ‘sales and customer service’, ‘caring, leisure and other service occupations’ and ‘skilled trades’.

Chart 4: Reason for inactivity by occupation in last job, as a proportion of all economically inactive, age 50-65, Q3 2022

This mirrors many of the structural inequalities faced by people in these jobs when they are in the labour market. The occupations with the lowest average pay are ‘elementary occupations’, ‘caring and leisure’ and ‘sales and customer services’, while those with the highest proportion of people in insecure work are ‘elementary occupations’, ‘process, plant and machine operatives’, ‘skilled trades’, and ‘care, leisure and other services’.12 Low pay and insecure work are also a barrier to building up occupational pensions as employers are not required to automatically enrol those earning less than £10,000 into a pension and many gig economy workers also miss out on pension contributions.13 So workers in these occupations will often face a double hit as they accrue less pension wealth to fund their retirement income and are forced out of work before reaching state pension age.

By contrast, almost two thirds (65 per cent) of economically inactive people whose last role was in a ‘professional occupation’ were retired while just one in ten were inactive due to long-term sickness. The other occupational groups where more than half of former workers who are inactive aged 50-65 classed themselves as retired were the high-earning ‘managers directors and senior officials’, ‘professionals’ and ‘associate professionals’, and ‘administrative and secretarial’.

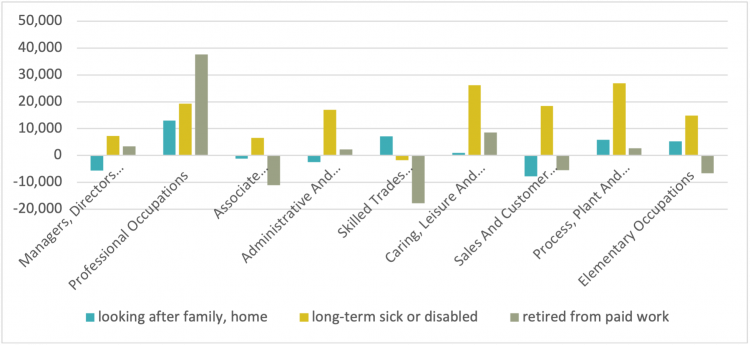

Trends over this period have exacerbated some of these inequalities. More than three quarters (77%) of the total increase in the number of people aged 50-65 unable to work due to ill health came from the five lowest paid occupational groups (see chart 5). While these sectors made up two in five jobs, they account for two in three older people who are too sick to work but used to be in employment.

There is one occupational group that goes against this trend linking rising inactivity linked to poor health. There was a substantial increase in the number of former professionals who had left the labour market before state pension age due to ill health, and an even bigger increase in the number of retirees from this sector. Although the high levels of income and wealth associated with this occupational group means they are more likely to be able to adequately fund an early retirement, the loss of professional expertise could also prove damaging to the wider economy.

Chart 5 - Increase in inactivity level by reason for inactivity and occupation, age 50-65, Q3 2019-Q3 2022

- 12 TUC, Insecure work - Why employment rights need an overhaul, July 2022 - https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-why-employment-rights-need-overhaul

- 13 Financial Times, Many in UK gig economy not getting pensions, regulator warns , June 2022 - https://www.ft.com/content/2894afb3-fef1-4fc9-8495-a89e01e5200e

Ethnicity

There are significant differences in levels of inactivity and reasons for inactivity between older white and BME populations. As with the disparities between different occupational groups, these often mirror structural inequalities in the labour market, with BME workers paid less on average than white workers, and more likely to face unemployment.[1]

Levels of economic inactivity are marginally lower among older BME people, which is likely to reflect barriers faced by many BME workers building up private pension savings, such as low pay and higher levels of insecure work[2], leading to lower levels of pension wealth.[3]

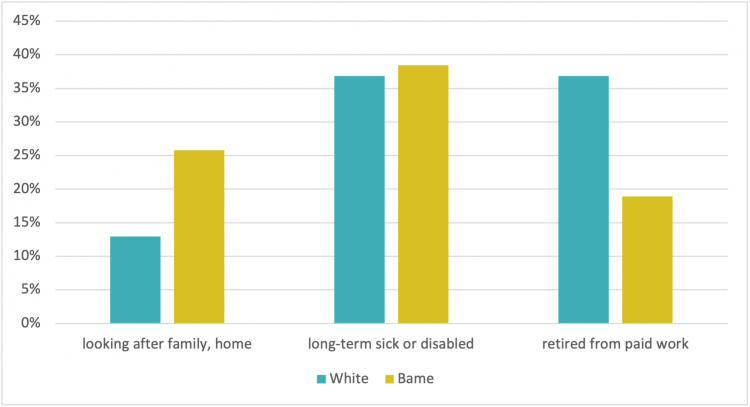

This means these workers are less likely to retire before reaching state pension age, with white people aged 50-65 who are economically inactive almost twice as likely as likely to be retired as BME counterparts (see chart 6). Economically inactive BME people are marginally more likely to have been forced out of the labour market by poor health, and twice as likely to cite caring responsibilities.

Chart 6 - Proportion of economically inactive by reason for inactivity and ethnicity, age 50-65, Q3 2022

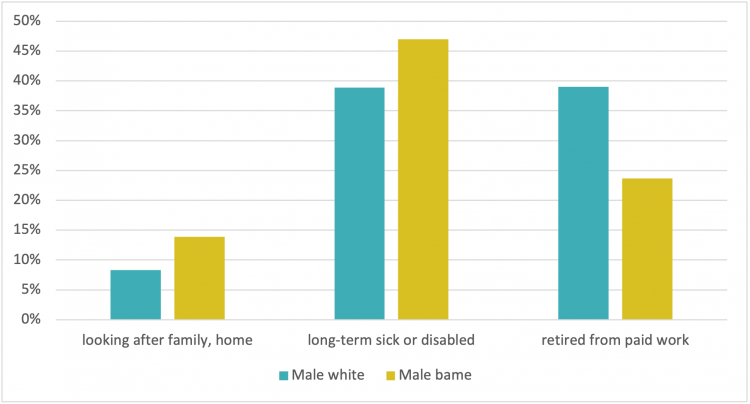

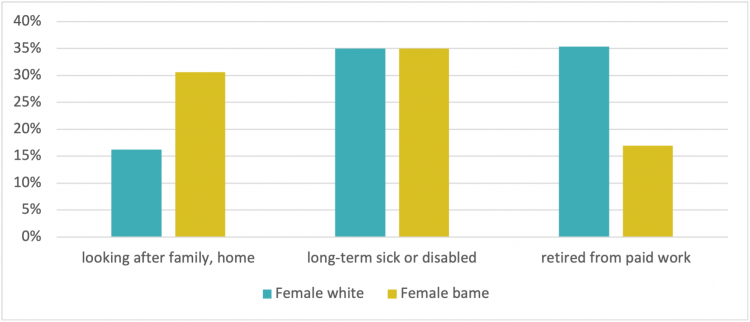

The differences are even more pronounced when gender is added to the analysis. BME men have substantially lower rates of inactivity than their white counterparts – just one in six BME men aged 50-64 had left the labour market (16 per cent), compared to one in four (25 per cent) white men. Among women this relationship was reversed with one in three white women in this age group economically inactive, compared to almost two in five (38 per cent) BME women.

The proportion of economically inactive BME men who were forced out of the labour market by ill health was 8 percentage points higher than for white counterparts, and the proportion unable to work because of caring commitments was 6 percentage points higher (See chart 7). The proportion of economically inactive BME and white women in ill health was the same, but the proportion of economically inactive older BME women who are unable to work because of caring commitments was twice as high as for economically inactive older white women (see chart 8), who are more than twice as likely to be retired.

Chart 7: Reason for inactivity as a proportion of all economically inactive by ethnicity, men aged 50-65, Q3 2022

Chart 8: Reason for inactivity as a proportion of all economically inactive by ethnicity, women aged 50-65, Q3 2022

Region

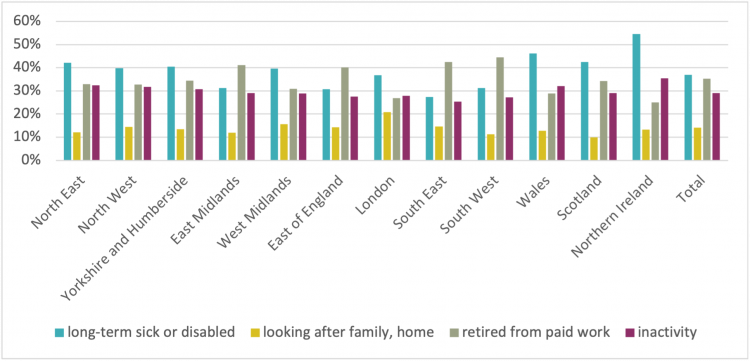

There are also stark differences between regions and nations. Northern Ireland showed the highest proportion of economically inactive older people who are in poor health at 55 per cent, followed by Wales at 46 per cent (See chart 9). Scotland, the North East, North West, and Yorkshire and Humberside also had above average proportions of inactivity due to long-term poor health among economically inactive older people.

Chart 9 – Reason for economic inactivity as a proportion of all economically inactive by region, age 50-65, Q3 2022

Policy

Policies to increase labour market participation would have multiple benefits, for older people who might otherwise leave work, and for the wider economy.

The government has recognised that declining labour market participation is an economic headwind that could limit the UK’s potential for growth. However, their proposals provide limited employment support as their approach to increasing labour market participation is increasingly based on imposing conditionality.

The Autumn 2023 statement included announcements on extending working lives, and the Governments back to work plan which expands work and health support. This plan also proposed reforms to the way people who fall ill interact with the social security system.[1] And just prior to this the government’s white paper on health and disability was published. This proposes significant cuts to benefit entitlements for some people with long term health conditions, who are expected to lose £400 a month compared to current system and face the threat of sanctions to enter employment.

The TUC are concerned by the approach proposed by government, as rather than providing genuine employment support to sick and disabled workers the proposals look set to threaten people into work via sanctions.

Policies must recognise the reasons why so many older people are not currently in work. Older people need extra support getting back into work, but the low levels of unemployment and rising economic inactivity among this group means labour market policies should be directed to not just those actively seeking employment through Jobcentres.

TUC Policy recommendations

- Older workers should be empowered to access the training they need to keep their skills up to date or to reskill for new roles to increase their ability to remain in employment. It is vital that the government provide targeted funding for over -50s to access training.

- The focus must be on providing good quality jobs, with the flexibility necessary for workers managing health conditions or juggling caring responsibilities. Rather than trying to force older people back to work through benefit sanctions or a rising state pension age.

- Urgent measures are required to improve people’s physical and mental health. The impact of underinvestment in the NHS on the ability of many people to work cannot be understated.

- Addressing inactivity needs a combination of targeted labour market support from the government and improved recruitment practices from employers.

Skills

There has been a decade of savage cuts to adult learning. Government investment in skills is set to be £1 billion lower in 2025 compared to 2010. [2] TUC commissioned research has shown a substantial decline in adult participation in FE and skills since 2010-11, with the number of learners more than halving to 2021-22. [3]

And older workers have long been less likely than their younger colleagues to be offered training by their employers, with workers in their 60s half as likely as those in their 20s to report having recently attended off-the-job training.[4] This affects workers’ ability to keep their skills up to date, damaging their chances of progression or changing jobs. It also limits their ability to reskill for new roles. This might be necessary if workers in physically demanding jobs need to move to less strenuous roles, and would also allow workers faced with the prospect of increasingly long working lives to make career changes in their 50s or 60s.

Mid-life skills reviews are an essential tool to allow workers to take stock of their skills, consider their future career path and identify any potential training needs. These need to be accessible in the workplace and online, rather than requiring people to attend Jobcentre Plus offices. The TUC has collaborated on a European project to develop mid-life skills reviews and an online Value My Skills tool[5] and unions also have a network of learning representatives in workplaces who are trained to support colleagues to use these tools.

It is also vital that the government provide targeted funded for over-50s to access training if required.

Job quality

It is unsurprising that increasing numbers of older people are opting out of a labour market that is beset by low pay and low-quality jobs. Wages have been stagnating for over a decade[6], while insecure work has increased.[7] The number of older workers on zero-hour contracts has doubled over the last decade.[8]

Moving from the one-sided flexibility of zero-hour contracts to a system of strengthened employment rights would also allow more older people to manage work around health issues and caring responsibilities. Three in five people in their fifties (58 per cent) who have left the labour market and three in ten (31 per cent) in their 60s say they would consider a return.[9] Of those who would consider returning to work, flexible working was the most important aspect of choosing a new job (36%), followed by working from home (18%) and something that fits around caring responsibilities (16%).

To give more people the chance to work flexibile there should be a day-one right to request flexible working for all workers with a right to appeal and no restrictions on the number of flexible working requests made. There should also be a legal duty on employers to consider which flexible working arrangements are available in a role and publish these in job advertisements, with the new postholder having a day-one right to take up the flexible working arrangements that have been advertised.

And as the percentage of people who are disabled increases among older age groups, addressing the barriers faced by disabled people in the workplace is also vital for increasing labour market participation. This requires ensuring that older workers who are disabled have access to the support they are legally entitled to and do not face discrimination. Employers must take all steps they can to ensure they comply with their proactive duty to implement reasonable adjustments for disabled workers, including flexible work patterns as soon as possible.

NHS

Tackling the NHS funding and recruitment crises that have resulted in a waiting list of over 6 million people in need of treatment will be key to helping more people stay in work.[10] As of September 2023, there were 121,070 vacancies in secondary care in England.[11]

To begin addressing these problems, we need a fully funded workforce strategy for the NHS, which includes building in restorative pay rises going forward.

Labour market support and recruitment

Older people who become unemployed face additional barriers when applying for jobs, with more than a third of over 50s saying they face age discrimination in the job market.[12] This results in a higher risk of facing long-term unemployment and ultimately dropping out of the labour market altogether.[13]

Addressing this needs a combination of targeted labour market support from the government and improved recruitment practices from employers. Employers should consider age as an equality, diversity and inclusion factor in their recruitment process, collect and scrutinise age data on their recruitment process, and ensure they remove age bias from their job adverts.[14]

The government must also recognise that the low unemployment rates among older people means that the route to increasing labour market participation among this group must focus on those not currently looking for work. The government should provide funding for local pilot schemes to help economically inactive people back into work, in combination with the measures outlined elsewhere to make jobs more flexible for those managing health or caring responsibilities.

In addition, there needs to be universal access to occupational health services, to provide for, rather than penalise, people with illness and injury, with medical advice and guidance on supported return to work. And to re-invest in safety regulation and enforcement: reverse the cuts to the HSE and local authority regulation, including inspectorate numbers, so that there is an effective deterrent to those employers who put workers in harms way.

While data on workplace discrimination faced by older people is limited, we do know that the negative workplace experience of older people are compounded for women, Black and Minority Ethnic (BME), LGBT+ and disabled workers. The existing legal framework has always had difficulty dealing with discrimination cases that are based on more than one ground, for example age and sex. The Equality Act 2010 contains limited provisions which if enacted would, allow tribunals to deal with cases of dual discrimination. We would be keen to see provisions of dual discrimination expanded to provide for cases of multiple discrimination.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox