Creating a healthy labour market

Over recent years, the number of people in the UK who are economically inactive has risen sharply. In total there are 440,000 more people who are neither in work nor looking for work now than there were before the Covid-19 pandemic began.

This has been largely driven by an increase in the numbers of older people leaving the labour market before they reach state pension age. This initially led to discussion of a ‘great retirement’, with the suggestion that older people were deciding to leave work early having re-evaluated their lives over the pandemic.

But the latest data is clear that the real story is that a growing number of people are simply too sick to work. While the number of people below state pension age who are retired has dropped below levels seen in 2019, the number who are out of work because of long-term ill health is nearly 340,000 higher than it was before the pandemic at almost 2.5 million.

This increase in poor health is seen across all age groups but was greatest among older people, who were already more likely to be out of work because of ill health. The result is 1.5 million men and women between 50 and state pension age out of work because of long-term sickness.

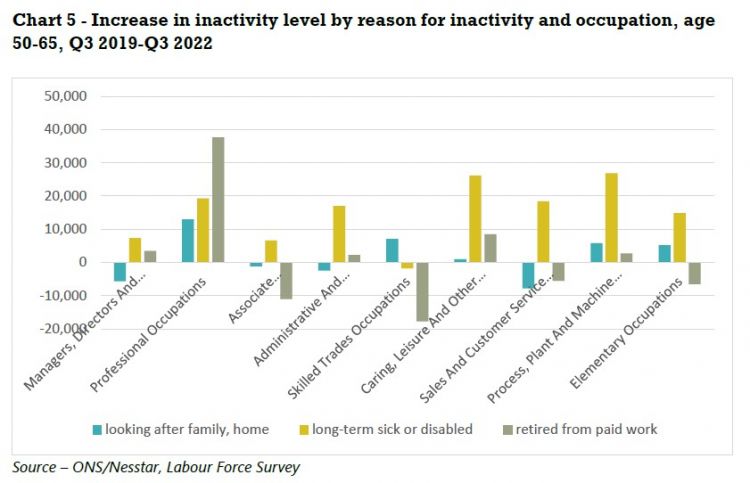

There is also an occupational divide between those who are likely to be forced out of work before they start drawing their state pension and those who are either able to stay in work longer or can afford to retire early.

These disparities often reflect the inequalities in our labour market. Among older workers inactive because of illness who had previously worked, two thirds had come from a job in one of the five lowest paid occupation groups, despite these groups accounting for just four in ten jobs.

And the gap is increasing, with people who used to work in these occupational groups accounting for more than three quarters of the increase in the number of people out of the work due to ill health.

Although the number of people out of work because of caring responsibilities has fallen over this period, it remains a significant factor. Older women are still more likely to be out of work because of caring responsibilities than older men, with BME women particularly impacted. Economically inactive older BME women are four times more likely than economically inactive older white men to be unable to work because of caring responsibilities.

The government has acknowledged the importance to the UK economy of persuading older people to stay in and return to the labour market. Chancellor Jeremy Hunt recognised this was necessary to “harness the full potential of our country” and “fix our productivity puzzle” and promised older workers he would “look at the conditions necessary to make work worth your while”.1

Helping those who are willing and able to work into their 50s and 60s will also improve the living standards of many. Leaving work before reaching state pension age can have a damaging impact on physical and mental health and reduce incomes before and after state pension age.

But increasing levels of economic activity will require a wide range of policies. The role of ill health in the increase seen in recent years means that restoring the NHS, tackling waiting lists and the recruitment and retention crisis, is a priority.

There are also a wide range of reforms to labour markets, social security, skills and working conditions that would enable more people in their 50s and 60s to stay in work:

- Older unemployed people do need extra support getting back into work as they face additional barriers in the job market, but low levels of unemployment and rising economic inactivity among this group means labour market policies should be directed at those not actively seeking employment through job centres.

- Rather than trying to force older people back to work through benefit sanctions or a rising state pension age, the focus must be on providing good quality jobs, with the flexibility necessary for workers managing health conditions or juggling caring responsibilities.

- Older workers should be empowered to access the training they need to keep their skills up to date or to reskill for new roles to increase their ability to remain in employment.

- In recognition of the fact that many older people who are too sick to work may never be able to return, the safety net needs to strengthened to prevent this resulting in severe hardship, and levels of workplace pension saving must be increased to give more people the financial resources to have control over how and when they stop paid work.

- 1 Jeremy Hunt speech at Bloomberg, January 2023 - https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/chancellor-jeremy-hunts-speech-at-bloomberg

Economic inactivity

Over the last three years the proportion of people in work in the UK has shrunk. Between January to March 2020 and October to December 2022 the employment rate for people aged 16-64 dropped from 76.3 per cent to 75.6 per cent. While the UK was not alone in seeing the numbers in work decline during the Covid-19 pandemic, it is unique among OECD countries in not seeing numbers bounce back to pre-pandemic levels.2 The fall in the employment rate was particularly pronounced among older workers (50-64), falling by 1.4 percentage points from 72.4 per cent to 71.0 per cent after a sustained period of increase from the 1990s.

Somewhat surprisingly, this fall in employment has been accompanied by a drop in unemployment rates. After a spike during the acute phases of the pandemic the overall unemployment rate is now 0.3 percentage points lower than it was at the start of 2020, while among the population aged 50-64 it is down 0.4 percentage points to 2.5 per cent.

With unemployment falling, the driver of our shrinking labour market has been a significant rise in economic inactivity. Over the period, the number of people aged 16-64 who were neither in work, nor looking for work, increased by around 440,000. This increase in inactivity was primarily the result of an increase of 337,000 in the number of people who were inactive because of long-term ill health and an extra 129,000 people in full-time education, offset by a small drop in retirements and a fall of 124,000 in the number out of the labour market because of caring commitments.

Again, this increase in inactivity was most pronounced for older workers. People aged 50-64 make up under a third of the working age population, but account for 64 per cent of the increase in inactivity.

Health

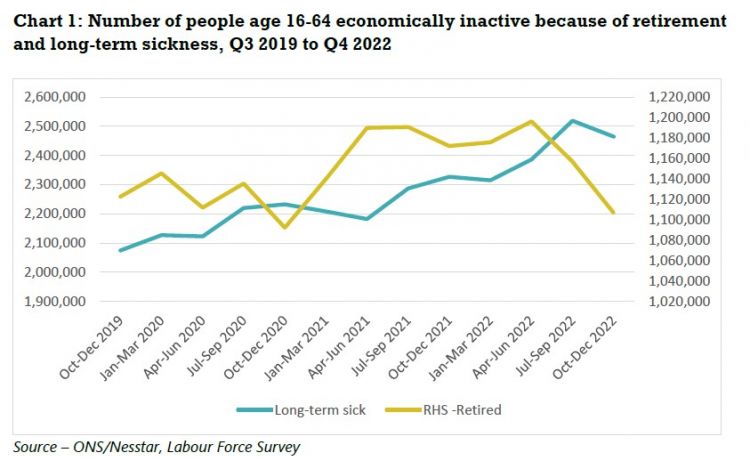

In some quarters, this was initially dubbed the ‘great retirement’, and there was a surge in the number of people aged 16-64 who were retired in the first half of 2021 (see chart 1). But this was followed by an equally strong decline in the second half of 2022, and the number of people in this age group who have retired from paid work is now below the level it was at going into the pandemic, at 1.1 million.

- 2 Financial Times, Chronic illness makes UK workforce the sickest in developed world, July 2022 - https://www.ft.com/content/c333a6d8-0a56-488c-aeb8-eeb1c05a34d2

By contrast, the number of people who are economically inactive because of poor health, although just below the peak reached in the third quarter of 2022 remains significantly higher than it was going into the pandemic, rising from 2.1 million in the first quarter of 2020 to 2.5 million in the fourth quarter of 2022.

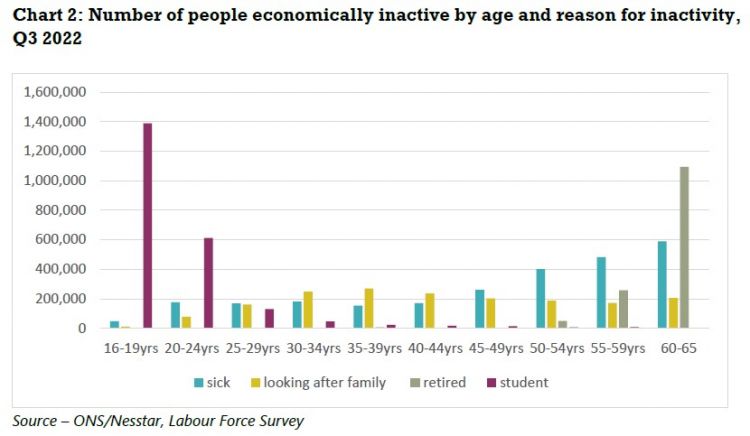

Older people are the most likely to be out of work because of long-term health conditions, with the numbers rising steadily once people reach their 40s (see chart 2). The numbers out of the labour market because of caring responsibilities is at its highest among people in their late 30s at 270,000, but there is considerably less variation in this figure across different ages, with more than 200,000 people aged 60-65 economically inactive because of caring responsibilities. While retirement becomes a factor in people’s 50s, the increase in ill health is far more significant. In total there are just over 880,000 people aged 50-59 who are too ill to work, and 300,000 who class themselves as retired.

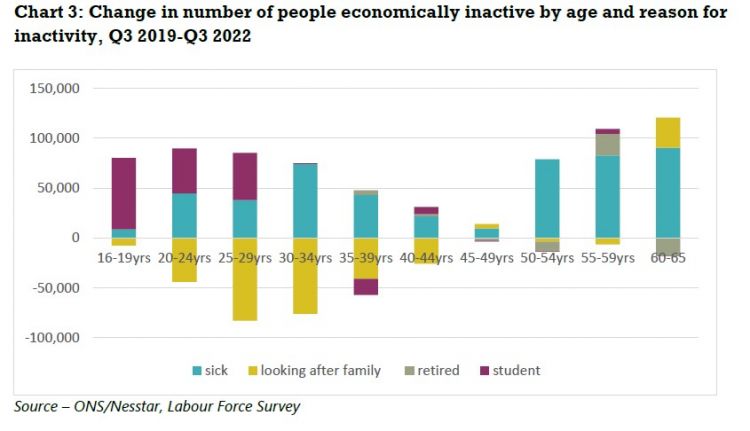

The rise in inactivity related to sickness over the last three years has also been fastest among older age groups, with an increase of more than 250,000 among people aged 50-65 over the period (see chart 3). This increase in poor health among this age group was mostly linked to physical conditions, with rises in the number of people unable to work because of conditions affecting feet and legs, back and neck, and chest or breathing issues, and there was also an increase in the numbers unable to work because of conditions linked to depression.

Although the biggest increase was reported among older age groups, between the third quarters of 2019 of 2022 there was a significant rise the number of under-40s unable to work because of health problems. There were an additional 200,000 people in their 20s and 30s out of the labour market for health conditions at the end of the period. This worrying rise was driven by an increase in issues related to mental health.

Occupation

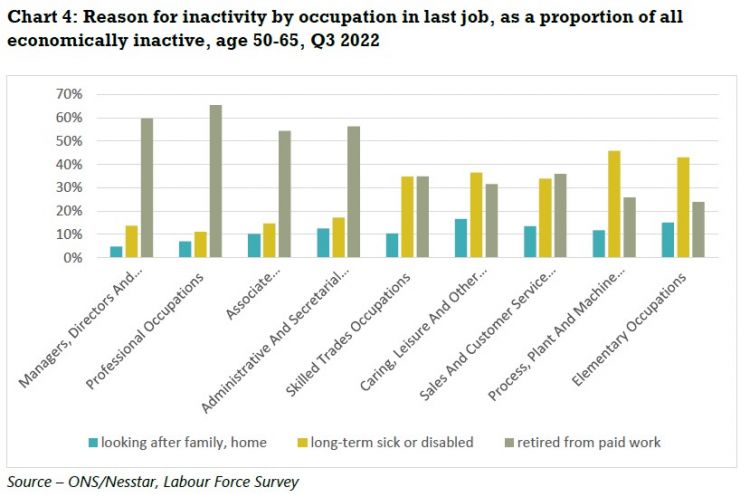

One of the most significant factors affecting whether someone is likely to be forced out of the labour market by ill health is the kind of work they do. People who are economically inactive because of long-term health conditions who have previously been in work are more likely to come from low paid occupations such as cleaning, caring, and retail work, or from physically demanding occupations such working with heavy machinery or in skilled trades. Economically inactive people who had previously worked in senior management positions or the professions are much more likely to have retired from paid work than to have been forced out by either ill health or caring responsibilities.

The occupational groups with the highest proportion of inactivity due to ill-health among the economically inactive are ‘process, plant and machine operatives’ (46 per cent) and ‘elementary occupations’ (43 per cent) which includes jobs such as cleaners and security guards (see chart 4). The other occupational groups with higher-than-average levels of inactivity due to poor health are ‘sales and customer service’, ‘caring, leisure and other service occupations’ and ‘skilled trades’.

This mirrors many of the structural inequalities faced by people in these jobs when they are in the labour market. The occupations with the lowest average pay are ‘elementary occupations’, ‘caring and leisure’ and ‘sales and customer services’, while those with the highest proportion of people in insecure work are ‘elementary occupations’, ‘process, plant and machine operatives’, ‘skilled trades’, and ‘care, leisure and other services’.3 Low pay and insecure work are also a barrier to building up occupational pensions as employers are not required to automatically enrol those earning less than £10,000 into a pension and many gig economy workers also miss out on pension contributions.4 So workers in these occupations will often face a double hit as they accrue less pension wealth to fund their retirement income and are forced out of work before reaching state pension age.

By contrast, almost two thirds (65 per cent) of economically inactive people whose last role was in a ‘professional occupation’ were retired while just one in ten was inactive due to long-term sickness. The other occupational groups in which more than half of former workers who are inactive aged 50-65 classed themselves as retired were the high-earning ‘managers directors and senior officials’, ‘professionals’ and ‘associate professionals’, and ‘administrative and secretarial’.

Trends over the last three years have exacerbated some of these inequalities. More than three quarters (77%) of the total increase in the number of people aged 50-65 unable to work due to ill health came from the five lowest paid occupational groups (see chart 5). While these sectors make up two in five jobs, they account for two in three older people who are too sick to work but used to be in employment.

There is one occupational group that goes against this trend linking rising inactivity linked to poor health. There was a substantial increase in the number of former professionals who had left the labour market before state pension age due to ill health, and an even bigger increase in the number of retirees from this sector. Although the high levels of income and wealth associated with this occupational group means they are more likely to be able to adequately fund an early retirement, the loss of expertise associated with this could prove damaging to the wider economy.

- 3 TUC, Insecure work - Why employment rights need an overhaul, July 2022 - https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-why-empl…

- 4 Financial Times, Many in UK gig economy not getting pensions, regulator warns , June 2022 - https://www.ft.com/content/2894afb3-fef1-4fc9-8495-a89e01e5200e

Ethnicity

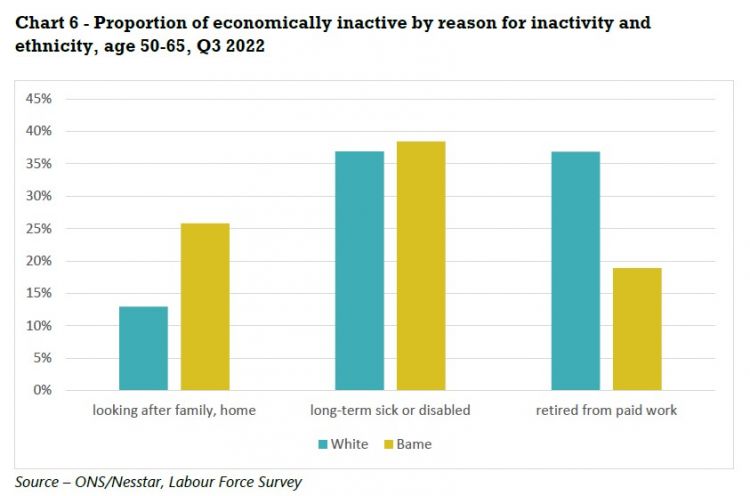

There are significant differences in levels of inactivity and reasons for inactivity between older white and BME populations. As with the disparities between different occupational groups, these often mirror structural inequalities in the labour market, with BME workers paid less on average than white workers, and more likely to face unemployment.5

Levels of economic inactivity are marginally lower among older BME people, which is likely to reflect barriers faced by many BME workers building up private pension savings, such as low pay and higher levels of insecure work6

, leading to lower levels of pension wealth.7

This means they are less likely to retire before reaching state pension age, with white people aged 50-65 who are economically inactive almost twice as likely as likely to be retired as BME counterparts (see chart 6). Economically inactive BME people are marginally more likely to have been forced out of the labour market by poor health, and twice as likely to cite caring responsibilities.

- 5 TUC, BME unemployment rate over twice as high as white workers – with gap widening through pandemic, May 2022 - https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/bme-unemployment-rate-over-twice-high-white…

- 6 TUC, Insecure work - Why employment rights need an overhaul, July 2022 - https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-why-empl…

- 7 This results in incomes from private pensions equivalent to just 62 per cent of the average – PPI, The Underpensioned Index, December 2022 -https://www.pensionspolicyinstitute.org.uk/media/4232/20221207-the-unde…

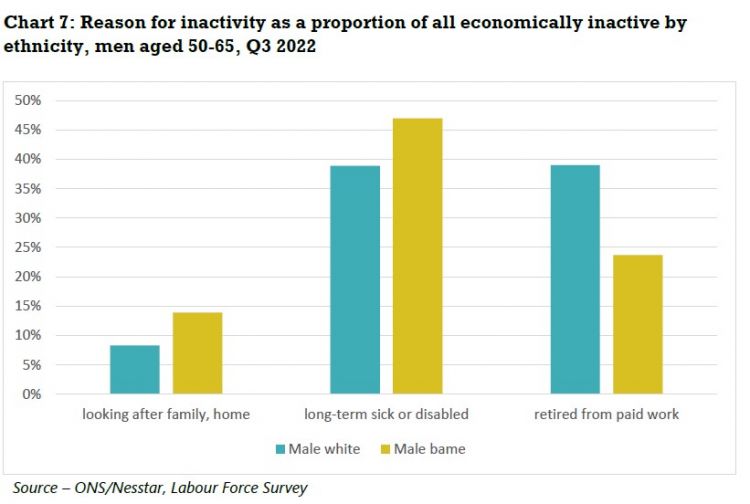

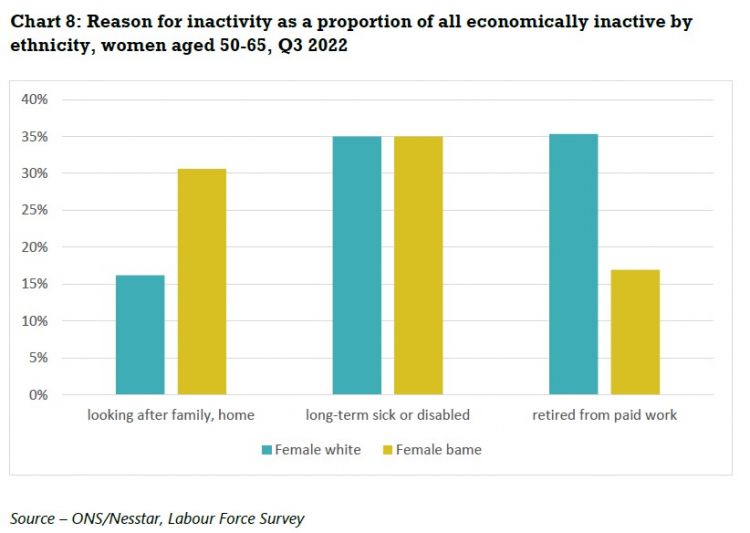

The differences are even more pronounced when gender is added to the analysis. BME men have substantially lower rates of inactivity than their white counterparts – just one in six BME men aged 50-64 has left the labour market (16 per cent), compared to one in four (25 per cent) white men. Among women this relationship is reversed with one in three white women in this age group economically inactive, compared to almost two in five (38 per cent) BME women.

The proportion of economically inactive BME men who were forced out of the labour market by ill health is 8 percentage points higher than for white counterparts, and the proportion unable to work because of caring commitments is 6 percentage points higher (See chart 7). The proportion of economically inactive BME and white women in ill health is the same, but the proportion of economically inactive older BME women who are unable to work because of caring commitments is twice as high as for economically inactive older white women (see chart 8), who are more than twice as likely to be retired.

Region

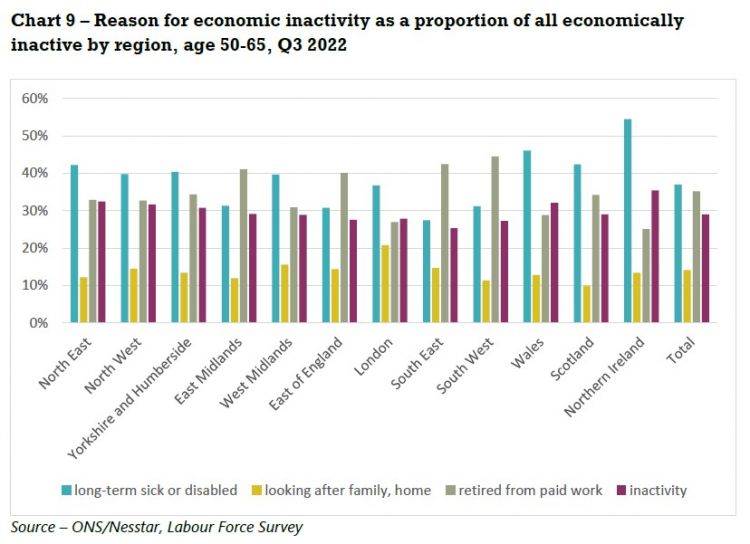

There are also stark differences between regions and nations. Northern Ireland has the highest proportion of economically inactive older people who are in poor health at 55 per cent, followed by Wales at 46 per cent (See chart 9). Scotland, the North East, North West, and Yorkshire and Humberside also had above average proportions of inactivity due to long-term poor health among economically inactive older people.

Policy recommendations

The government has recognised that declining labour market participation is an economic headwind that could limit the UK’s potential for growth. It announced a package of measures last July increasing the support available to older people through job centres,8 and is expected to produce a white paper on boosting participation rates shortly.

As well as the threat to economic growth, rising economic inactivity also harms the living standards of many older people and increases the risks of poverty in old age, particularly when combined with an increasing state pension age. Research into the impact of the increase in the state pension age from 65 to 66 found that many workers had been unable to respond to this by staying in work, leading to a severe drop in incomes for many. This caused absolute income poverty rates among 65-year-olds to more than double from 10% to 24%.9

Qualitative research into the experiences of people in their 50s and 60s reveals many of those on low pay, managing health conditions or out of work face severe hardship and feel powerless to improve their finances.10

The risk is particularly acute for workers in their early 50s who have left the labour market, with less than half of this group confident that they could fund their retirement.11

So policies to increase labour market participation would have multiple benefits, for older people who might otherwise leave work and also for the wider economy. But these policies must recognise the reasons why so many older people are not currently in work.

Older unemployed people do need extra support getting back into work, but the low levels of unemployment and rising economic inactivity among this group means labour market policies should be directed at those not actively seeking employment through job centres.

- Rather than trying to force older people back to work through benefit sanctions or a rising state pension age, the focus must be on providing good quality jobs, with the flexibility necessary for workers managing health conditions or juggling caring responsibilities.

- Older workers should be empowered to access the training they need to keep their skills up to date or to reskill for new roles to increase their ability to remain in employment.

- In recognition of the fact that many older people who are too sick to work may never be able to return, the safety net needs to strengthened to prevent this resulting in severe hardship, and levels of workplace pension saving must be increased to give more people the financial resources to have control over how and when they stop paid work.

- Urgent measures are required to improve people’s physical and mental health. Although this report focuses on measures relating to work and the labour market, the impact of underinvestment in the NHS on the ability of many people to work cannot be understated.

Skills

Older workers have long been less likely than their younger colleagues to be offered training by their employers, with workers in their 60s half as likely as those in their 20s to report having attended off-the-job training recently.12 This affects their ability to keep their skills up to date, damaging their chances of progression or changing jobs. It also limits their ability to reskill for new roles. This might be necessary if workers in physically demanding jobs need to move to less strenuous roles, and would also allow workers faced with the prospect of an increasingly long working life to make career changes in their 50s or 60s.

Mid-life skills reviews are an essential tool to allow workers to take stock of their skills, consider their future career path and identify any potential training needs. These need to be accessible in the workplace and online, rather than requiring people to attend job centres. The TUC has collaborated on a European project to develop mid-life skills reviews and an online Value My Skills tool13 and unions also have a network of learning representatives in workplaces who are trained to support colleagues to use these tools.

It is also vital that the government provide targeted funded for over-50s to access training if required.

Job quality

It is unsurprising that increasing numbers of older people are opting out of a labour market that is beset by low pay and low-quality jobs. After more than a decade of flat average wages, 2022 saw a 3.4 per cent drop in average wages, while the number of older workers on zero-hour contracts has doubled over the last decade.14

Measures to get pay rising across the economy, such as increasing public sector pay and reversing restrictive anti trade union laws, would potentially tempt some of those who have chosen to retire early back into work.

Moving from the one-sided flexibility of zero-hour contracts to a system of strengthened employment rights would also allow more older people to manage work around health issues and caring responsibilities. Three in five people in their fifties (58 per cent) who have left the labour market and three in ten (31 per cent) in their 60s say they would consider a return.15 Of those who would consider returning to work, flexible working was the most important aspect of choosing a new job (36%), followed by working from home (18%) and something that fits around caring responsibilities (16%).

To give more peoples the chance to work flexibility there should be a day-one right to request flexible working for all workers with a right to appeal and no restrictions on the number of flexible working requests made. There should also be a legal duty on employers to consider which flexible working arrangements are available in a role and publish these in job advertisements, with the new postholder having a day-one right to take up the flexible working arrangements that have been advertised.

And as the percentage of people who are disabled increases among older age groups, addressing the barriers faced by disabled people in the workplace is also vital for increasing labour market participation. This requires ensuring that older workers who are disabled have access to the support they are legally entitled to and do not face discrimination. Employers must take all steps they can to ensure they comply with their proactive duty to implement reasonable adjustments for disabled workers, including working from home and flexible work patterns as soon as possible.

NHS

Tackling the NHS funding and recruitment crises that have resulted in a waiting list of 7.2 million people in need of treatment will be key to helping more people stay in work. NHS England is operating short of almost 133,000 staff due to unfilled vacancies, representing a vacancy rate of just under 10 per cent, while social care faces an even more severe staffing crisis, with the equivalent of 165,000 jobs.

This is compounded by a wider squeeze on funding, with average day-to-day spending on health in the UK, between 2010 and 2019 18 per cent lower than the European average.

To begin addressing these problems, we need a fully-funded workforce strategy for the NHS, sustainable long-term funding for health and social care, and an immediate pay rise for all NHS workers, including outsourced porters, cleaners, caterers and security staff. This must cover pay for 2022/23 and build in restorative pay rises going forward.

A stronger safety net

The sharp falls in income and increases in poverty rates among older people caused by the inability of growing numbers to work until they reach state retirement age show the need for a stronger safety net. This must include early access to an unreduced state pension for those approaching state pension age who are unable to work because of ill-health or caring responsibilities, and the lowering of the age at which people are eligible for pension credit, to boost incomes for the poorest households.

Reforming Universal Credit so that it provides an income recipients can live on and doesn’t punish older workers with modest levels of savings would also ensure a decent safety net for those forced out of the labour market.

The government should also publish its independent review of the state pension, which was completed in October, as soon as possible, to allow public scrutiny and debate before it publishes its own recommendations. The TUC believes the stalling life expectancy and growing inequalities of health and life expectancy, and the damaging impact on people just below state pension age of previous increases, means plans for further increases should be shelved.

As well as a strengthened social security system, workplace pensions also need to do more to support low paid workers in retirement. Extending auto-enrolment would bring in more low paid and part-time workers, and setting out a timetable for increasing employer contributions would give people greater financial security as they plan for retirement or manage their workload. As a first step the government must make good on its promise to implement the recommendations of the 2017 Automatic Enrolment Review to lower the age threshold for auto-enrolment to 18 and remove the lower earnings limit so that contributions are calculated from the first pound of earning by the mid-2020s.

Labour market support and recruitment

Older people who become unemployed face additional barriers when applying for jobs, with more than a third of over 50s saying they face age discrimination in the job market.16 This results in a higher risk of facing long-term unemployment and ultimately dropping out of the labour market altogether.17

Addressing this needs a combination of targeted labour market support from the government and improved recruitment practices from employers. The £22m in funding announced for this by the government and the creation of 50 Plus champions to provide specialised support for older jobseekers are welcome steps. But evidence of a rapid rise in the use of sanctions against older Universal Credit claimants is concerning.18

Employers should consider age as an equality, diversity and inclusion factor in their recruitment process, collect and scrutinise age data on their recruitment process, and ensure they remove age bias from their job adverts.19

The government must also recognise that the low unemployment rates among older people means that the route to increasing labour market participation among this group must focus on those not currently looking for work. The government should provide funding for local pilot schemes to help economically inactive people back into work, in combination with the measures outlined elsewhere to make jobs more flexible for those managing health or caring responsibilities.

- 8 DWP, Government drive to help those aged 50 and over re-join the jobs market, November 2022 - https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-drive-to-help-those-aged-…

- 9 IFS, How did increasing the state pension age from 65 to 66 affect household incomes?, June 2022 - https://ifs.org.uk/publications/how-did-increasing-state-pension-age-65…

- 10 Age UK, Waiting for an age, January 2023 - https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publ…

- 11 ONS, Reasons for workers aged over 50 years leaving employment since the start of the coronavirus pandemic: wave 2, September 2022 https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmen…

- 12 CIPD, Understanding older workers, March 2022 - https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/understanding-older-workers-report_tcm18-…

- 13 Union Learn, Mid-life skills review project - https://www.unionlearn.org.uk/mid-life-skills-review-project

- 14 TUC, 2022 was the worst year for real wage growth since current records began, February 2023 https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/labour-market-2022-was-worst-year-real-wage…

- 15 ONS, Reasons for workers aged over 50 years leaving employment since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, March 2022 - https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmen…

- 16 Centre for Ageing Better, Too much

Experience, February 2021 - https://ageing-better.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-02/too-much-exper… - 17 Rest Less, 50% of unemployed men aged 50+ are out of work for at least a year, February 2022 - https://restless.co.uk/press/50-of-unemployed-men-aged-50-are-out-of-wo…

- 18 Byline Times, Sanctions on Older Benefits Claimants Rise Amid Government ‘Concerns about Labour Supply’, February 2023 - https://bylinetimes.com/2023/02/20/revealed-sanctions-on-older-benefits…

- 19 Centre for Ageing Better, Good recruitment for older workers, October 2021 - https://ageing-better.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-10/GROW-a-guide-f…

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox