Sexual harassment of LGBT people in the workplace

#MeToo has been effective in focusing the eyes of the world on the problem of sexual harassment at work. But the voices of LGBT people haven’t been heard clearly enough in discussions around this issue. We wanted to change this and foreground LGBT people’s voices and experiences in the ongoing debate and search for solutions. We therefore conducted the first survey of its kind on this issue.

We found shockingly high levels of sexual harassment and sexual assault.

Around seven out of ten LGBT workers experienced at least one type of sexual harassment at work (68 per cent) and almost one in eight LGBT women (12 per cent) reported being seriously sexually assaulted or raped at work.

However, this is a hidden problem with two thirds of those who were harassed not reporting it; and one in four of those who did not report the harassment being silenced by fear of ‘outing’ themselves at work.

Government must act urgently to put the responsibility for tackling this problem where it belongs – with employers. We need stronger legislation that places a new legal duty on employers to prevent sexual harassment, with real consequences for those who don’t comply.

Download full report (PDF)

For over a year we’ve been listening to the voices of the #MeToo movement – to the thousands of stories about sexual harassment and sexual assault at work. The stories that were shared echoed the findings of our 2016 report Still Just a Bit of Banter and shed light on the lives of women whose experiences of workplace sexual harassment were all too often dismissed, normalised and swept under the carpet.

The wave of disclosures that has swept across the country, through industry after industry, is both welcome and empowering, shining a powerful light on experiences that have too long been marginalised and ignored.

However, the voices of LGBT people have rarely been heard on this issue and very little in-depth research has been carried out to properly understand their experiences. We know from our previous research on LGBT people at work that their experience of the workplace is all too often marked by prejudice and hostility.1

Why we conducted the research

We wanted to understand LGBT people’s experience of sexual harassment at work and make sure that when government, regulators, employers and unions develop their responses to the epidemic of sexual harassment that #MeToo has revealed, the experiences and needs of LGBT people are at the heart of this. We therefore carried out the first specifically targeted research of its kind in the UK, seeking the views of more than 1,000 LGBT people on their experience of sexual harassment at work. We not only asked about instances of sexual harassment but also whether people had felt able to report it and what impact the sexual harassment had on their physical and mental health.

Main findings

Our findings were shocking. Around seven out of ten (68 per cent) LGBT people who responded to our survey reported being sexually harassed at work, yet two thirds didn’t report it to their employer. One in four of those who didn’t report were prevented from raising the issue with their employer by their fear of being ‘outed’ at work.

The research found unacceptably high levels of sexual harassment across all different types of harassing behaviours for both LGBT men and women.

LGBT women responding to our survey experienced higher levels of sexual harassment and sexual assault in many areas. There were also some areas where men and women reported similar levels of sexual harassment.

The difference in experience was particularly apparent in reported instances of unwanted touching, sexual assault and rape at work.

LGBT women are:

- more than twice as likely to report unwanted touching (35 per cent*2 of women compared to 16 per cent of men).

- almost twice as likely to report experiencing sexual assault. More than one fifth (21 per cent*) of women compared to 12 per cent of men

- almost twice as likely to experience serious sexual assault or rape. Around one in eight women (12 per cent*) compared to one in fourteen (7 per cent) of men.

Many of the incidents of sexual harassment that we were told about appeared to be linked to the sexualisation of LGBT identities and the misconception that these identities solely focus on sexual activity. People influenced by these stereotypes see being lesbian, gay, bisexual or trans as an invitation to make sexualised comments or ask inappropriate questions about an LGBT person’s sex life, particularly if an individual is ‘out’.

A number of those responding to our survey described a range of longer-term impacts caused by their experience of sexual harassment at work. Around one in six people (16 per cent) reported a negative effect on their mental health and a similar proportion (16 per cent) left their job as a result of being sexually harassed.

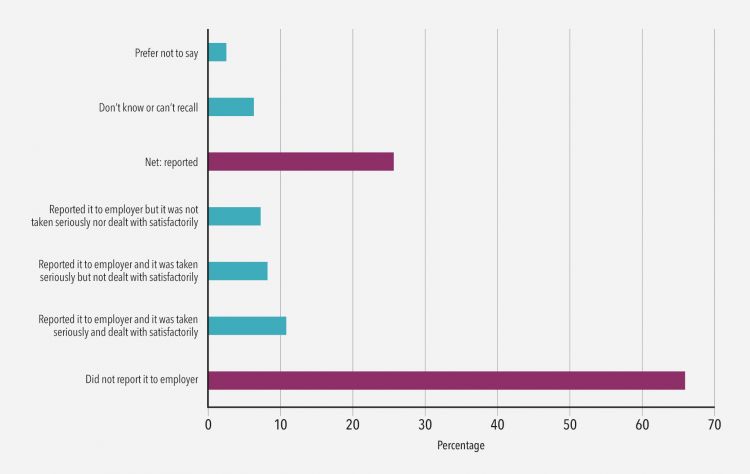

Two thirds of respondents who had been sexually harassed or sexually assaulted at work had not reported the most recent incident to their employer.

More than half (57 per cent) of those that hadn’t reported said that this was because they thought there would be a negative impact on their relationships at work if they did. Over four in ten (44 per cent) said they didn’t report because they feared a negative impact on their career.

One in four had not reported because it would have revealed their sexual orientation and/or gender identity.

What unions want

Importantly, our findings also tell us that being a union member makes a real difference to people’s experience. Union members were more likely to report their experiences of sexual harassment to their employer (32 per cent vs 22 per cent non-union members), more likely to say it was taken seriously (27 per cent vs 15 per cent non-union members), and more likely to say it was dealt with satisfactorily (17 per cent compared to eight per cent of workers who were not union members).

But workplace cultures need to change. This will only happen on the scale that we need if government introduces a new legal duty on employers to take preventative steps to stop sexual harassment happening.

We also need to strengthen the role of key regulators such as the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and reintroduce and improve legislation to protect workers from third-party harassment.

Every employer must take a zero-tolerance approach to all forms of discrimination and harassment (and sexual harassment).

Defining sexual harassment

This report focuses on the sexual harassment of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people at work. The Equality Act 2010 defines sexual harassment as unwanted conduct of a sexual nature which has the purpose or effect of violating someone’s dignity, or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for them.

It is important to note that a perpetrator’s claim that a comment or action was meant as a joke or a compliment is not a defence in a sexual harassment case. Nor does the harassment have to be directed at the person complaining about it. For example, the display of pornography in a work environment or sexual comments directed at others may create a degrading, intimidating or hostile working environment for workers even if they are not intended as the object of the comments. It is also harassment to treat someone less favourably because they have rejected or been subjected to unwanted sexual conduct.

Some examples of behaviour that could constitute sexual harassment are:

- indecent or suggestive remarks

- questions, jokes, or suggestions about a colleague’s sex life

- the display of pornography in the workplace

- the circulation of pornography (by email, for example)

- unwelcome and inappropriate touching, hugging or kissing

- requests or demands for sexual favours

- any unwelcome behaviour of a sexual nature that creates an intimidating, hostile or humiliating working environment.

Who is affected by sexual harassment and where does it occur?

Everyone and anyone can experience sexual harassment at work. However, women are more likely to experience sexual harassment than men. TUC research found that more than half (52 per cent) of women experience some form of sexual harassment in the workplace.3 This statistic was echoed by a 2017 poll by the BBC, which found that 50 per cent of women reported experiencing sexual harassment compared to 20 per cent of men.4

The sexual harassment and sexual assault of women at work sits within a wider, systemic experience of violence against women and girls at home, in education and in public and digital spaces. It is part of the everyday context of the lives and experiences of women and girls across the UK. As the Women and Equalities Select Committee noted in their report on sexual harassment in public places, harassment is, “a routine and sometimes relentless experience for women and girls, many of whom first experience it at a young age.”5 When looking at women’s experience of sexual harassment and assault it is clear that some groups, including Black and minority ethnic (BME), disabled and LGBT women are affected in different and disproportionate ways, their particular experience being shaped by structural discrimination and pervasive, harmful stereotypes.

Workplace sexual harassment can take place in a range of different locations. For example, a client or patient’s home, on a work trip, a team away-day or at a work social event such as a Christmas party.

Social media and email are increasingly involved in workplace sexual harassment. Our report, Still Just a Bit of Banter 6 which looked at sexual harassment of women in the workplace found that one in twenty women had been sexually harassed by email or online.7

As well as taking different forms and occurring in diverse settings, sexual harassment at work may be perpetrated by people in a range of roles, including managers, potential employers, colleagues, clients, patients, or customers. For example, a care worker might be harassed by a client when on a home visit or a prospective employer might demand sexual favours of an actor at a casting session. Sexual harassment perpetrated by a client, contractor or customer is referred to as third-party harassment.

What do we know about LGBT people’s experience of sexual harassment at work?

Very little is known about the true extent of sexual harassment of LGBT people in the workplace.

The most recent research into LGBT people’s experience of workplace sexual harassment was conducted by the Government Equalities Office (GEO). This found that one per cent of LGBT people, who had been in a job for the 12 months preceding the survey, had experienced sexual harassment or violence at work.8

However, this finding was based on a short, single question within a wider survey which did not attempt to define sexual harassment or contextualise it for LGBT people. A similar approach was adopted in the last government survey which collected general data on sexual harassment at work. This also found that one per cent of people report being sexually harassed at work.9 It is therefore not surprising that the recent GEO research found such a small proportion of LGBT workers reporting sexual harassment.

Researching LGBT people’s experiences of sexual harassment in the workplace is complicated by the fact that most LGBT workplace research and interventions to date have focused on homophobic harassment and bullying.

Following the start of the #MeToo movement, sexual harassment in the workplace has had a high profile in the media and been the focus of attention by government, regulators and employers. However, LGBT people’s experiences have not tended to be discussed as part of this.

The lack of representation of LGBT people’s experiences within public discussion of sexual harassment and the fact that when sexual harassment occurs it may be mixed with trans-, bi- or homo- phobia might be a barrier for LGBT people to identify their experiences as sexual harassment.

As with other forms of sexual harassment, several other barriers exist that complicate attempts to quantify incidents of sexual harassment. These include the normalisation of sexually harassing behaviours in the workplace and wider society, victims’ unwillingness to share their experiences, even anonymously, and a reluctance to name what happened to them as sexual harassment. 10

Methodology

In order to better understand LGBT people’s experiences of sexual harassment at work, the TUC commissioned in-depth research. In November 2018, we surveyed 1,001 adult LGBT workers in Great Britain, who had worked within the last five years.

We did not set quotas as the exact profile of the LGBT population is not known and therefore the findings of our original set of 1,001 are not weighted.

To ensure a better balance between the number of responses from men and women, we gathered a further 150 responses from LGBT women, who had worked within the last five years, in January 2019.

The responses were combined with those from LGBT women from the main sample. The combined responses of women from the main survey plus the additional responses are referred to as the women-only sample and indicated through this report with an *.

We know from our previous work that the best way of getting an accurate picture of the prevalence of sexual harassment at work is not to simply ask people whether they have experienced it. This is because there are low levels of understanding of the full range of behaviours which meet the legal definition of sexual harassment in the workplace and also because individuals can be reluctant to label their experience as sexual harassment. 11 We therefore mirrored the approach adopted in our earlier sexual harassment research,12 listing a range of different types of sexual harassment and asking whether people had experienced these. We also used specific examples drawn from LGBT workers’ experiences of sexual harassment to contextualise the different types of harassment and ensure that LGBT workers were more easily able to relate to them.

The research examined the following aspects of sexual harassment of LGBT workers:

- unwelcome verbal sexual advances (eg suggestions that sex with an individual from the opposite sex will make you ‘straight’)

- unwelcome jokes of a sexual nature (eg jokes about gay men being promiscuous or lesbians needing a man)

- unwelcome questions/ comments about your sex life (eg questions about how you have sex your role, etc)

- comments of a sexual nature about your sexual orientation

- comments of a sexual nature about your gender identity

- hearing colleagues make comments of a sexual nature about a straight colleague in front of you

- hearing colleagues make comments of a sexual nature about a lesbian/gay woman, gay man, bisexual or trans colleague in front of you

- receiving unwanted emails with material of a sexual nature

- receiving unwanted messages with material of a sexual nature over social media from colleagues

- displays of pornographic photographs or drawings in the workplace

- unwanted touching (eg placing hand on lower back or knee)

- sexual assault (unwanted touching of the breasts, buttocks or genitals, attempts to kiss)

- serious sexual assault or rape.

Our survey also allowed participants to share written details of specific incidents of sexual harassment and assault. Throughout the report we have illustrated our findings with quotes and examples drawn from these responses. Where sources are not indicated, they all come from this research. We have also used quotes drawn from previously unpublished, qualitative information submitted by LGBT workers to The Cost of Being Out at Work survey.13

- 3TUC (2016) Still Just a Bit of Banter? Sexual harassment in the workplace

- 4BBC (2017) ‘Half of women’ sexually harassed at work – bbc.co.uk/news/uk-41741615

- 5Women’s Equalities and Select Committee (2018) Inquiry into Sexual Harassment of Women and Girls in Public Places

- 6TUC (2016) Still Just a Bit of Banter? Sexual harassment in the workplace, page 17

- 7Ibid

- 8Government Equalities Office (2018) National LGBT Survey: research report, page 150

- 9Business Innovation and Skills (2008) Fair Treatment at Work Report: findings from the 2008 survey

- 10TUC (2016) Still Just a Bit of Banter? Sexual harassment in the workplace

- 11EOC (2007) Sexual Harassment in the Workplace: a literature review, Working Paper Series No. 59

- 12TUC (2016) Still Just a Bit of Banter? Sexual harassment in the workplace

- 13TUC (2017) The Cost of Being Out at Work: LGBT+ workers’ experiences of harassment and discrimination. This survey was conducted on Survey Monkey between 1 March and 14 May 2017 and was promoted on social media, receiving 5,074 responses. Of these, 412 respondents provided a written response detailing their experiences of sexual harassment in the workplace.

Our research revealed that around 7 out of 10 (68 per cent) respondents had experienced at least one form of sexual harassment at work.14

Figure 1 shows positive responses to the question, “Have you ever experienced any of the following sorts of unwanted sexual behaviour at work?”

- 14Six-hundred-and-eighty-one respondents to our polling of 1,001 LGBT respondents said they had experienced unwanted sexual behaviour in the workplace in the past.

Respondents were asked about each different type of behaviour and were invited to select one of the following answers in relation to each behaviour listed:

- Total yes

- Yes, within the last 12 months

- Yes, more than 12 months ago.

Our research found shockingly high levels of sexual harassment and sexual assault at work across all different types of harassing behaviours for both LGBT men and women.

LGBT women experienced significantly higher levels of sexual harassment and sexual assault in a range of areas, including unwelcome sexual messages, sexual advances and sexual assault. These variations are discussed below. 15 There were also other areas where men and women reported similar levels of sexual harassment.

- 15 Where such differences are set out they are the differences between the women-only sample and the sample of GBT men drawn from the main survey.

The research found unacceptably high levels of sexual harassment across all different types of harassing behaviours for both LGBT men and women.

Comments about other workers

Hearing comments of a sexual nature about a lesbian, gay man, bisexual or trans colleague was the behaviour that most respondents reported, with just under half experiencing it (47 per cent). Many LGBT workers also reported hearing comments of a sexual nature about straight colleagues in front of them with over four in ten being exposed to those behaviours. (44 per cent)

Comments about respondents

Over four in ten (43 per cent) LGBT workers reported hearing comments of a sexual nature about their sexual orientation and three in ten (30 per cent) heard comments of a sexual nature about their gender identity.

One gay man described comments that colleagues had made about his sexuality including “one member of staff asking if I ‘take it up the arse’, and when I said I was unhappy about being asked this being told I was ‘a flouncy old queen.’” 36- to 45-year-old, gay, man, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

A lesbian reported receiving verbal abuse from a colleague. Things like “I wonder if she pervs on us” said to her and other staff colleagues, sometimes in front of customers. 26- to 35-year-old, lesbian, woman, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

“[After] I had disclosed I was bi/pansexual, a male colleague came up to me in the pub and said I ‘must have had some great threesomes then!?’ He said my male partner must be lucky. And laughed. It wasn’t funny. It felt gross. I felt unsafe and that as per usual my sexuality had been reduced to the sexual pleasure of others, something ‘dirty’.” 26- to 35-year-old, bisexual, gender – other, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

Unwelcome jokes of a sexual nature

Around half of respondents (47 per cent) reported they had heard unwelcome jokes of a sexual nature at work. A number of respondents reported that these sexualised ‘jokes’ related directly to their sexual orientation, often including negative discriminatory stereotypes.

More than half (53 per cent*) of LGBT women had experienced unwelcome jokes of a sexual nature, as had over four in ten gay, bisexual and trans (GBT) men (44 per cent).

A lesbian respondent described being asked about her relationship and then being exposed to unwelcome jokes about her and her partner having sex and her being the ‘male.’ 25- to 34-year-old, lesbian, woman, BME

Another respondent said he was often exposed to “jokes about the promiscuity of gay men, ie they are all [having sex] like rabbits.” 35- to 44-year-old, gay, man

Unwelcome questions or comments

Over two fifths (42 per cent) of respondents reported hearing colleagues make unwelcome comments or ask unwelcome questions about their sex life.

Around half (47 per cent*) of LGBT women had experienced unwelcome questions/comments about their sex life, as had four in ten GBT men.

A number of respondents noted that these comments or questions were far more intrusive and explicitly sexualised than those that their heterosexual colleagues were exposed to.

“My supervisor has asked me how I have sex with my fiancé. If I use toys etc.” 26- to 35-year-old, lesbian, woman, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

I was repeatedly asked in front of my peers whether I was ‘the train or the tunnel’ and whether I had ‘sucked off’ my partner on my lunch. When I raised the fact that this was embarrassing me and I felt uncomfortable I was told I was being melodramatic and over-reacting.

“I was working in a kitchen environment and the chefs would regularly … make derogatory comments, and at one point I walked into a room in the middle of them discussing gang raping me.” 19- to 25-year-old, trans, lesbian, gender – other, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

Many individuals who shared their experiences of this type of behaviour expressed discomfort at the comments or questions. However, the frequency of this behaviour and the fact that it occurred unchallenged resulted in some individuals viewing it as part of the normal work environment even though they stated it was unwanted.

Unwelcome verbal sexual advances

Over a quarter (27 per cent) of respondents reported receiving unwelcome verbal sexual advances in the workplace.

Around a third (32 per cent*) of LGBT women had experienced unwelcome verbal sexual advances, as had one in four GBT men.

A consistent theme that emerged from the qualitative evidence from respondents around unwelcome sexual advances was that these were often accompanied by comments around how heterosexual sex could make lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB) people straight.

I was told that all I needed was a good dick inside me and I’d be straight and also what a waste it was for all men that I was a lesbian.

Another lesbian told us about how a small group of males who [she] considered friends as well as colleagues had a bet/game of sorts to try and ‘turn her’ and were overly flirty/letchy on work nights out. 26– to 35-year-old, lesbian, woman, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

Lesbians and bisexual women respondents most frequently told us about hearing these kinds of comments/jokes or unwelcome verbal sexual advances in their qualitative responses. However, some bisexual, gay and trans men also reported similar experiences.

“Sexual harassment was someone with their suspicions, trying to ‘straight’ me.” 26- to 35-year-old, BME, bisexual, man, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

Sexualisation

Many of the experiences and incidents of verbal sexual harassment LGBT people experience link to the sexualisation of LGBT identities and the misconception that these focus on, and are intrinsically linked to, sex. This influences the view that being ‘out’ is an open invitation to make sexualised comments or ask inappropriate questions about an LGBT person’s sex life. As one respondent explained:

“I was subjected to inappropriate questions from others, including professionals, and when I refused to answer, I was told I shouldn’t be out if I didn’t want to talk about it (including details of my sex life).” 46- to 55-year-old, lesbian, woman, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

One group that were particularly affected by this were bisexual people. A number of written responses from bisexual people described harassment that appeared to be directly influenced by specific discriminatory stereotypes related to the sexualisation of bisexuals. One bisexual woman reported hearing ‘jokes’ that “no one is safe” around her. 35- to 44-year-old, bisexual, woman

“A male colleague in a position of power over me at work … started asking me very uncomfortable questions about my sex life when he learned I was bisexual … Throughout the exchange, he seemed threatened by my sexuality and insecure about his own, as if my sexuality was a challenge to his way of life and he needed to correct me in some way.” 19- to 25-year-old, bisexual, woman, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

“I don’t see anyone else being asked details about what and how they do things in bed, comments about not going into the toilets with me...” 46- to 55-year-old, bisexual, man, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

Unwelcome sexual messages and exposure to pornography

Around one in six respondents (17 per cent) reported receiving unwanted emails with materials of a sexual nature in them and 16 per cent had seen displays of pornographic photographs or drawings in the workplace. Around one in seven (15 per cent) reported receiving unwanted messages with material of a sexual nature over social media from colleagues.

A male colleague at work got hold of my mobile number from a colleague under false pretences. I got sent text messages and emails I’d class as sexually harassing.

Over one in five (21 per cent*) of LGBT women had experienced receiving unwanted messages with material of a sexual nature over social media, as had around one in eight (13 per cent) GBT men.

“I received unwanted emails of a sexual and suggestive nature which progressed to them attempting to touch me in person.” 25- to 34-year-old, lesbian, woman

Our findings reveal extremely high levels of LGBT workers reporting unwanted touching, unwanted attempts to kiss them or unwanted touching of their breasts, buttocks or genitals in the workplace; incidents which could be defined as sexual assault under UK law. Both LGBT men and women also reported high levels of serious sexual assault and rape at work.

However, LGBT women were significantly more likely to report all of these experiences than the men who responded to our survey.

We found:

More than a third of women (35 per cent*) who responded to our survey had experienced unwanted touching, for example placing hands on their lower back or knee, compared to around one in six men (16 per cent).

More than one fifth (21 per cent*) had experienced sexual assault, for example unwanted touching of the breasts, buttocks or genitals, attempts to kiss, compared to one in eight men (12 per cent).

One in eight (12 per cent*) LGBT women had been seriously sexually assaulted or raped at work, compared to one in fourteen men (seven per cent).

Qualitative evidence from this research and The Cost of Being Out at Work survey shows that many lesbian and bisexual women have experienced verbal sexual harassment from men at work, which included threats of unwanted sexual activity aimed at ‘turning them straight.’ These threats link to a specific form of targeted sexual violence experienced by lesbian and bisexual women where sexual assault and rape are used as a way of punishing and ‘curing’ them of their sexual orientation. This is also known as ‘corrective rape.’ 16

One lesbian reported an escalating scale of sexual harassment that started with comments about turning her straight and escalated to unwanted touching and sexual assault.

- 16 Corrective rape is a hate crime where a person is targeted because of their perceived sexual or gender orientation. The common intended consequence of the rape, as seen by the perpetrator, is to ‘correct’ the person’s orientation, to turn them heterosexual, or to make them ‘act’ more in conformity with gender stereotypes.

Touching my breasts on a work night out… trying to kiss me… it was related to turning me straight and trying to show me what I am missing.

Although in many areas there were differences between the experiences of men and women who responded to our survey, the experiences of bisexual men and women were similar across several different types of sexual harassment and sexual assault at work, including sexual assault and rape.

Around one in five bisexual men and women who responded to our survey experienced sexual assault at work (20 per cent and 22 per cent* respectively) and one in ten reported being seriously sexually assaulted or raped at work (11 per cent and 10 per cent* respectively).

One bisexual woman described being sexually assaulted by a colleague and the negative response of her manager who witnessed it.

My manager saw the whole thing and when I complained, he said that I ‘must like that thing because I am a bi woman.

...The manager said I had ‘brought it upon myself’ and, as I was a fairly new employee, I ‘wasn’t worth as much’ as the man who sexually assaulted me.” 19- to 25-year-old, bisexual, woman, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

“A colleague at my last job undid my bra and groped my breasts.” 19- to 25-year-old, bisexual, woman, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

“Was sexually assaulted during work hours. My supervisor thought it was hilarious and decided to call every shop in the company to tell everyone about it. They made fun of me for weeks.” 26- to 35-year-old, bisexual, man, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

Not enough trans men responded to the survey for us to reliably report these findings separately.

Trans women 17 were even more likely than other women to experience sexual assault and rape at work, with around one third of trans women (32 per cent*) who responded to our survey reporting being sexually assaulted and over one in five (22 per cent*) experiencing serious sexual assault or rape.

One trans woman described her experience of “unwanted touching from a manager in charge” who had, “a curiosity about my breast growth.” 46- to 55-year-old, trans, woman, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

- 17 Fifty trans women responded to the survey. This is considered to be on the threshold of the minimum number of responses required for results of a sub-group to be considered robust and reliable enough to allow for analysis.

Our findings also showed that LGBT people’s experience of sexual harassment and assault at work varied significantly depending on the respondent’s ethnicity.

- More than half of lesbian, bisexual and trans BME women 18 (54 per cent*) who responded to our survey reported unwanted touching compared to around one third of white women (31 per cent*).

- BME women were more than twice as likely to report being sexually assaulted at work (45 per cent* BME, 18 per cent* white) and almost three times more likely to experience serious sexual assault or rape (27 per cent* BME, nine per cent* white).

- 18 Forty-nine BME women responded to the survey. This is considered to be on the threshold of the minimum number of responses required for results of a sub-group to be considered robust and reliable enough to allow for analysis.

A number of Black feminist academics and activists have highlighted the specific oppression faced by BME women and the fact that Black women have experienced sexual violence differently than white women. This includes the ‘othering’ and eroticising of BME women’s bodies and sexuality.19

In most areas BME gay, bisexual and trans men reported the same rates of sexual harassment as white men. In two areas BME men experienced higher rates of harassment than white men.20

- Four in ten gay, bisexual and trans BME men who responded to our survey reported unwelcome verbal sexual advances compared to just over two in ten (23 per cent) GBT white men.

- 27 per cent of gay, bisexual and trans BME men reported being exposed to displays of pornographic photographs or drawings in the workplace compared to 15 per cent of GBT white men.

- 19 TUC (2016) Still Just a Bit of Banter? Sexual Harassment in the workplace

- 20 Fifty-one BME men responded to the survey. This is considered to be on the threshold of the minimum number of responses required for results of a sub-group to be considered robust and reliable enough to allow for analysis.

Although the research found statistically similar rates of workplace sexual harassment of BME gay, bisexual and trans men, and their white counterparts, it is likely the way sexual harassment is expressed differs depending on race, as highlighted by a number of Black academics and activists. Given the lack of qualitative information gathered which raised these issues, this report is unable to distinguish these differences.

Disabled people reported significantly higher levels of sexual harassment than non-disabled people.

The research found that disabled men reported significantly higher levels of sexual harassment than non-disabled men and non-disabled women across all aspects of sexual harassment.

Disabled women reported significantly higher levels of sexual harassment than both disabled men and non-disabled men and women across most areas. However, there were three types of harassment where disabled men experienced higher levels than disabled women. Those were:

- hearing colleagues make comments of a sexual nature about a straight colleague (56 per cent compared to 54 per cent* of disabled women)

- hearing colleagues make comments of a sexual nature about a lesbian/gay woman, gay man, bisexual or trans colleague (60 per cent compared to 55 per cent* of disabled women)

- displays of pornographic photographs or drawings in the workplace (32 per cent compared to 29 per cent* of disabled women).

Disabled women were:

- around twice as likely to report unwanted touching (50 per cent* disabled women, 26 per cent* non-disabled women),

- more than twice as likely to report sexual assault (38 per cent* vs 14 per cent*) and

- six times more likely to experience serious sexual assault or rape (24 per cent* vs 4 per cent*).

These higher rates of sexual harassment and assault in our research reflect previous studies which showed that disabled women and girls experience gender-based violence at disproportionately higher rates and in unique forms owing to discrimination and stigma based on both gender and disability. 21

- 21See UNFPA, Addressing Violence Against Women and Girls in Sexual and Reproductive Services: a review of knowledge assets (New York, UNFPA, 2010) and Stephanie Ortoleva and Hope Lewis, Forgotten Sisters — a Report on Violence Against Women and Disabilities: an overview of its nature, scope, causes and consequences, North-Eastern University School of Law Research Paper No. 104-2012 (2012)

Disabled men’s reported levels of sexual harassment and assault were lower than those of disabled women but significantly higher than non-disabled men. Disabled men were almost:

- three times more likely to report unwanted touching when compared to non-disabled men (32 per cent compared to 11 per cent)

- five times more likely to report unwanted sexual assault than non-disabled men (28 per cent compared to six per cent)

- seven times more likely to report serious sexual assault and rape that non-disabled men (twenty per cent compared to three per cent.).

Two thirds of respondents who had been sexually harassed or sexually assaulted at work had not reported the most recent incident to their employer.

We asked people why they hadn’t reported being sexually harassed to their employer and let respondents select more than one option in recognition of the fact there might be multiple factors behind their decision.

More than half (57 per cent) chose not to report harassment to their employer because they thought there would be a negative impact on their relationships at work.

More than four in ten (44 per cent) thought there would be a negative impact on their career if they reported the unwanted sexual behaviour to their employer and four in ten did not believe the person responsible for the sexual harassment would be sufficiently punished.

Embarrassment was another prevalent factor behind the decision not to report, with over a third (37 per cent) citing this reason. Around a quarter (26 per cent) did not report being sexually harassed because they did not think they’d be believed. Around one in seven respondents (15 per cent) said they did not know they could report the sexual harassment to their employer.

A quarter of respondents said they didn’t report being sexually harassed because it would have revealed their sexual orientation and/or gender identity.

A number of qualitative responses mentioned that the reason they didn’t report being sexually harassed was because they had seen other occasions when harassment of LGBT staff was not taken seriously.

Most people who reported being sexually harassed were dissatisfied with their employer’s response. Only around one in ten (11 per cent) of those who reported being sexually harassed thought it was both taken seriously and dealt with satisfactorily.

Around one in twelve (eight per cent) of those who reported thought their complaint was taken seriously but not dealt with satisfactorily and seven per cent reported the sexual harassment but did not think it was taken seriously or dealt with satisfactorily.

Gay men’s experience of reporting

Gay men were less likely than other groups to report their experiences of sexual harassment to their employer.

Around three quarters (72 per cent) of gay men did not report the sexual harassment to their employer compared to 67 per cent* of lesbians/gay women and 62 per cent of bisexuals.

Once I was grabbed by the genitals at a Christmas party by a female colleague. She said it was okay because neither of us have anything to worry about. I wish I had reported it now, but didn’t.

Where gay men had reported their experience of sexual harassment they were less likely than others to say it was taken seriously and dealt with satisfactorily.

Only seven per cent of gay men who had reported being sexually harassed said it was it was taken seriously and dealt with satisfactorily compared to 13 per cent* of lesbians and 13 per cent of bisexuals.

I reported sexual harassment to work place and nothing was done about it... the perpetrator was asked if he had been indiscreet and he denied it so it was brushed under the carpet.

Only around a quarter of respondents (26 per cent) reported the most recent incident of sexual harassment to their employers.

Of those who did report, over four in ten (43 per cent) thought they were treated less well because they had reported the incident.

Although few of the LGBT workers had reported being sexually harassed to their employer, many more (40 per cent) had confided in someone else. However, around the same proportion (37 per cent) of respondents said they had told no-one about the most recent incident.

Union membership and reporting

Union members were more likely to report their experiences of sexual harassment to their employer and say it was taken seriously and dealt with satisfactorily.

Around one third (32 per cent) of union members reported their most recent experience of sexual harassment to their employer, compared to 22 per cent of workers who were not union members.

Where union members reported sexual harassment, they were more likely to say it was taken seriously: 27 per cent compared to 15 per cent of workers who were not union members.

Union members also had higher levels of satisfaction with the action that employers took in response to reported sexual harassment. Around one in six (17 per cent) who reported sexual harassment said it was both taken seriously and dealt with satisfactorily, compared to eight per cent of workers who were not union members.

Impact

Our survey findings revealed the substantial impact that sexual harassment had on LGBT people across a range of measures. One in five said it had made them feel less confident at work. For around one in six people (16 per cent) the impact of the harassment was so severe that it caused them to leave their job. For one in twenty-five the experience was so unbearable it caused them to leave their job without another job to go to.

Around one in six people (16 per cent) said the harassment had a negative effect on their mental health, including making them feel more stressed, anxious, depressed, while four per cent of respondents said the harassment had a negative impact on their physical health.

Characteristics of perpetrators

The research asked respondents who had experienced sexual harassment at work to describe who had carried out the most recent incident.

For the majority of respondents, (70 per cent) the most recent harasser was a colleague.

Respondents were fairly evenly split in terms of how closely they worked with the person who harassed them; 26 per cent reporting the most recent harasser was a colleague they worked closely with and 28 per cent reporting being harassed by a colleague they did not work closely with.

Around one in eight people (12 per cent) had been harassed by their direct manager or another manager.

Manager example:

The manager would make inappropriate comments, touch my breasts, bottom and stroke my clothing in my genital area… He targeted people he viewed as being weak so the disabled, long-term unemployed and BME people.

Colleague example:

I was with a colleague who was asking about my same-sex partner (and husband) who is 16 years older than me. My colleague felt it appropriate to ask questions like “how does that work then?” They also asked me if I use any of the apps such as Grindr and if I have ever met anyone from them and done anything. It made me feel very uncomfortable.

Third-party harassment

One in five (20 per cent) respondents who had experienced sexual harassment told us their most recent harasser was a third party, such as a customer, client or patient, supplier or contractor.

I heard a supplier contractor making suggestive comments about gays wanting sex all the time and that ‘they’ would do it with anyone if given the chance.

“I work in a pub. A few regulars seem to be fascinated by the intimate details of my sex life, often asking questions about it. Once had a customer, who I was asking to leave, call me a faggot and threaten to sodomise me with a pool cue.” 19- to 25-year-old, gay, man, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

Where the harassment is perpetrated by a client or customer, the person experiencing the harassment may feel it is even harder to act and that they have less protection from their employer. 22

Where the harassment took place

We asked respondents who had experienced sexual harassment at work where the most recent incident had happened.

- 22 TUC (2016) Still Just a Bit of Banter? Sexual harassment in the workplace

The majority of respondents said they had been sexually harassed on work premises

(63 per cent). However, around one in ten (11 per cent) reported being harassed at a work-related social event, such as a Christmas or client party.

Around one in twelve (eight per cent) reported the harassment took place at another location for work reasons, for example at a conference.

“A male colleague attempted to grope and kiss me when drunk at a work party – he did not and does not know I am gay.” 26- to 36-year-old, lesbian, gender – other, The Cost of Being Out at Work survey

One in twenty LGBT workers reported being sexually harassed on a work visit, for example in a patient or client’s place of work or home. The same proportion reported the harassment was online, for example by email or on social media.

Our research has highlighted the extent of sexual harassment LGBT workers face, the barriers they experience in reporting it and the significant impact it has on their lives.

Existing legal protections and workplace initiatives are not addressing the scale and seriousness of this issue. Additional legal protections and new ways of tackling sexual harassment are needed and if they are to be successful, they must be designed to include the specific experiences of LGBT people.

Government

The government must take steps to ensure LGBT workers are effectively protected from sexual harassment and sexual assault in the workplace.

Our research has shown that most LGBT workers who’ve been sexually harassed don’t report it to their employers. LGBT workers face specific additional barriers in reporting sexual harassment, with the fear of ‘outing’ themselves preventing 25 per cent of those who didn’t report being sexually harassed from coming forward. We can’t therefore rely on reactive systems which are driven by reports from workers.

Workplace cultures will not change while the onus rests solely on individuals who are silenced by hostile workplaces. We need to shift the onus of dealing with sexual harassment at work from these individuals to employers.

- Introduce a new legal duty to prevent harassment. The government must introduce a mandatory duty for employers to protect workers from all forms of harassment (including sexual harassment) and victimisation. A breach of the duty should constitute an unlawful act for the purposes of the Equality Act 2010 and be enforceable by the EHRC. This would create a clear and enforceable legal requirement on all employers to safeguard their workers and help bring about cultural change in the workplace.

- Introduce a statutory code of practice on sexual harassment and harassment at work. This must be LGBT inclusive and use the findings of this report supported by meaningful engagement with the LGBT community to inform the drafting of the code. The code should also specify the steps that employers should take to prevent and respond to sexual harassment, and which can be considered in evidence when determining whether the mandatory duty has been breached.

- Strengthen legislation to tackle third-party harassment. Employers currently have a duty of care for all workers; however, in relation to third party harassment is not always clear to employers or workers what this means. The government must reintroduce section 40 of the Equality Act 2010 which places a duty on employers to protect workers from third-party harassment. Government should also strengthen it by removing the requirement that an employer needs to know that an employee has been subjected to two or more instances of harassment before they become liable. This would ensure clear and comprehensive legal protection on the grounds of sexual harassment. 23

- Strengthen evidence base. In any future research exploring sexual harassment at work, government should ensure that the distinct experiences of LGBT people are analysed. Government should also build on the findings set out in this report by conducting further research to explore the experiences of the specific groups that experienced the highest levels of sexual harassment and sexual assault at work, with a particular focus on LGBT BME women, disabled women and trans men where additional research would address current evidence gaps.

- Funding for specialist services. Many services, both in the public and voluntary sectors, have faced years of underfunding and resource cuts. The government must ensure there is adequate funding for organisations combating sexual violence and providing support to survivors of sexual violence. It is particularly important that LGBT, women’s and BME women’s services receive adequate levels of funding so that LGBT workers are able to access services tailored for them.

- Reinstating employment tribunals’ power to make wider recommendations. The Equality Act 2010 gave employment tribunals the power to make wider recommendations for the benefit of the wider workforce, not just the individual claimant, in relation to discrimination claims. This power was removed by the Deregulation Act 2015. In workplaces where a culture of bullying and harassment has been allowed to flourish or where there are systemic failures of the organisation to respond adequately to complaints of harassment, the power to make wider recommendations would be of great benefit.

Regulatory bodies

- Guidance for employers. The EHRC should in the short term, before any statutory code of practice is published, issue LGBT-inclusive guidance for employers on how to address sexual harassment in the workplace that is LGBT inclusive and uses the findings of this report to identify specific difficulties facing the LGBT community for inclusion within the guidance.

- Strengthen the role of regulatory bodies. Given the worryingly high levels of workplace sexual harassment, sexual assault, serious sexual assault and rape the research found, there is a clear need for greater activity, including enforcement activity, by regulatory bodies such as the EHRC which has responsibility for equality legislation, and the HSE, which has responsibility to ensure the risks of encountering harassment and violence at work are assessed and prevented or controlled. The government should work with these organisations to coordinate an appropriate response to the findings of this research and are provided with the necessary resources to do this.

Employers

The research found very few LGBT workers reported sexual harassment to their employer, and that one quarter of them felt unable to bring a complaint for fear of ‘outing’ themselves: revealing their sexual orientation or gender identity. To address this employer should:

- Make all work policies inclusive. Ensure all their policies, including those on harassment and sexual harassment, are LGBT inclusive, using appropriate language, examples and case studies. All staff should receive training on these policies, including new staff in their induction, so that the whole workforce understands the policy and their role in ensuring the workplace is free from sexual harassment and victimisation.

- Review existing policies. Workplace policies should be reviewed in light of this report, with the relevant unions’ involvement to ensure that workers’, including LGBT workers’, complaints of sexual harassment are taken seriously and resolved to the workers’ satisfaction. Employers should work with recognised trade unions when developing these policies.

- Adopt a zero-tolerance approach. Employers should take a zero-tolerance approach to all forms of discrimination and harassment (and sexual harassment). This should include workplace policies and training, including what bystanders should do to challenge harassment. Where such incidents do occur, there should be clear disciplinary procedures in place for the perpetrator and support for the victim.

- Training. HR and all levels of management should receive training on sexual harassment, what constitutes sexual harassment, stalking and online harassment, relevant law and workplace policies, and how to respond to complaints of sexual harassment. In some workplaces, training for all staff may be appropriate.

Trade unions

The research found overall low reporting levels of sexual harassment. However, among those who had experienced sexual harassment, union members were significantly more likely to report it. Around one third (32 per cent) of union members reported their sexual harassment. Unions can negotiate better policies and support members to resolve ongoing issues.

- Review guidance and training. Unions should review their guidance and training for reps on how to support members who have been sexually harassed to ensure they are LGBT inclusive.

- Review employer policies on sexual harassment. Unions should work with employers to review their policies on sexual harassment, to ensure they are LGBT-inclusive by using appropriate language, examples and case studies throughout.

- Negotiate robust workplace policies. Any policy that aims to tackle harassment, abuse or violence should clearly define the behaviours, and recognise the employer’s duty to prevent and/or deal with any harassment from third-parties. Unions may want to collect anonymised information about members’ experiences of third-party harassment, abuse or violence to help strengthen negotiations with an employer.

- Workplace campaigns. Run workplace campaigns and organising. Trade unions should publicise the support they can offer in all cases of harassment, abuse and violence and proactively target recruitmentWorkplace campaigns. Run workplace campaigns and organising. Trade unions should publicise the support they can offer in all cases of harassment, abuse and violence and proactively target recruitment

- 23

Section 40 of the Equality Act 2010 placed a duty of the employer to act where an employee was being harassed by a third-party in certain circumstances. This was repealed in 2013.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox