Jobs and recovery monitor - update on young workers

In our latest recession report, we take another look at the impact of the pandemic on young workers.

The pandemic has hit young workers hard. Youth unemployment is rising and almost two-thirds of those who have lost jobs since the start of the pandemic are young workers. Youth unemployment is particularly impacting young black and minority ethnic (BME) people. During the pandemic, the unemployment rate for BME young workers has increased more than twice as fast as the unemployment rate for young white workers.

It’s vital that action is taken to address a youth unemployment crisis. As young workers are more likely to be furloughed, it’s important that the government does not end the scheme prematurely. We also need a revamp of the disappointing Kickstart scheme, investment in job creation, and a strong safety net for those who do lose jobs.

Job losses since the start of the pandemic

Payroll data: 450,000 lost jobs

During the pandemic, the ONS has been publishing the number of payrolled employees according to Pay As You Earn (PAYE) Real Time Information (RTI). This gives a timelier insight into job losses, and is currently the best way to look at the number of employees as the ONS has warned that the number of employees given by the Labour Force Survey data should be used with caution.

The PAYE data[1] shows the clear impact of the pandemic on young workers. The number of payrolled employees aged under 25 fell by around 450,000 (12%) between January 2020 and February 2021. With overall job losses of 700,000 across the period, this means that 65 per cent of job losses between January 2020 and February 2021 were among those aged under 25.

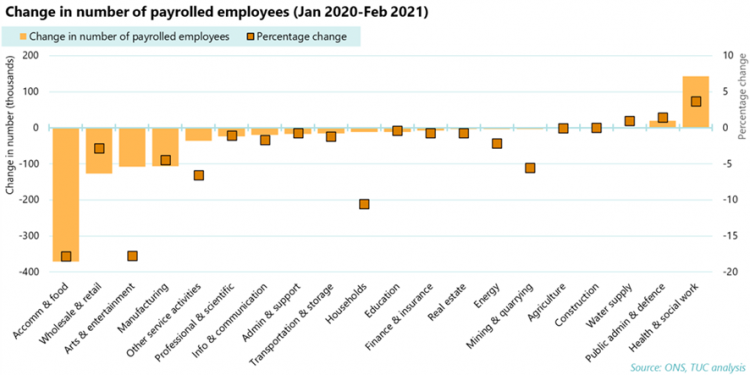

Job losses by industry

A key reason behind young workers being more likely to lose their jobs during the pandemic is the industries they work in. Young workers are overrepresented in the industries hit hardest by the pandemic.

The accommodation and food service industry has seen the most job losses throughout the pandemic, with 370,000 jobs (18%) lost. Going into the pandemic (Jan-March 2020), 15 per cent of workers aged 25 and under worked in accommodation and food, compared to just 4 per cent of those over 25.

The three industries with the highest job losses (accommodation and food, wholesale and retail, and arts and entertainment) are also the three industries with the highest percentage of young workers in their workforce[2].

[1] Earnings and employment from Pay As You Earn Real Time Information, seasonally adjusted, ONS (2021). Data used in this release is the 23 March 2021 release. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/

[2] Young workers are most at risk from job losses due to the coronavirus crisis, TUC (2020). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/young-workers-are-most-risk-job-losses-due-coronavirus-crisis

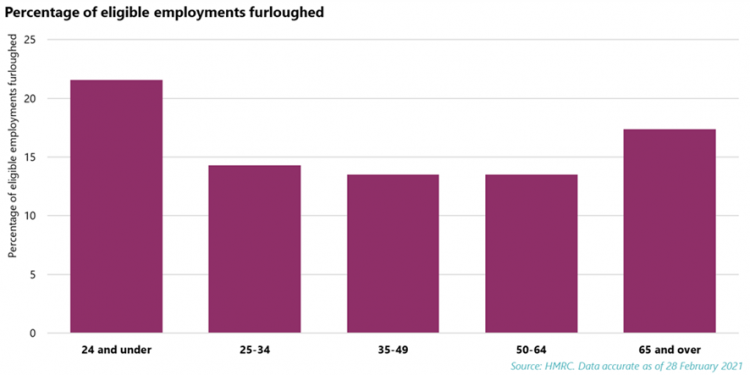

The furlough scheme

The industry connection also helps to explain why young workers are much more likely to be furloughed. Over one-fifth (22 per cent) of young workers are furloughed as of 28 February 2021, higher than any other age group[1]. This leaves young workers vulnerable to changes to the scheme, such as the planned winding down and end of furlough.

It also affects the pay of young workers. Furloughed employees are guaranteed 80% of their wages, but there’s no provision to prevent workers falling below the minimum wage while they’re furloughed.

Young workers already face lower minimum wage rates and furlough pushed many below this inadequate wage floor. 423,000 16-24 year olds were paid below the minimum wage in April 2020, compared to 64,000 the previous year[2].

[1] Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme statistics: March 2021, HMRC (2021). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-march-2021

[2] Jobs paid below minimum wage by category, ONS (2020). Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/datasets/

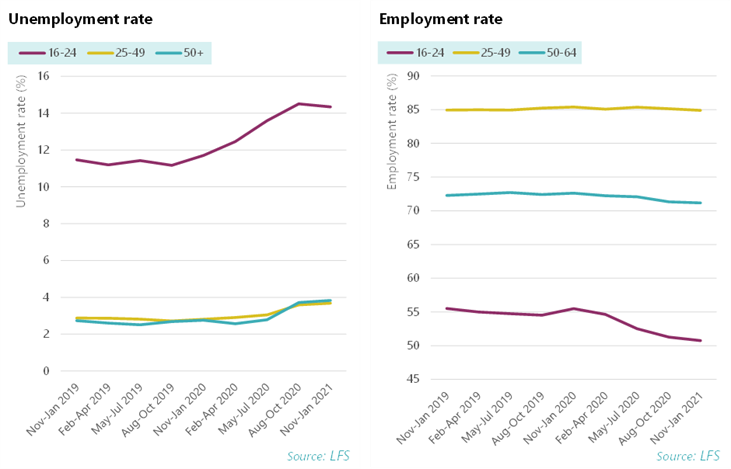

Labour market data: unemployment rates

Youth unemployment

Unemployment rates tend to always be higher for young workers. This has worsened over the pandemic as unemployment has risen mostly among young people. The unemployment rate for 16-24 year olds is now over 14%, compared to just under 4% for those over 25[1].

Employment rates tend to be lowest for young people. Again, young people have seen this worsen more rapidly than other working age people. The employment rate for 16-24 year olds is 51% compared to 85% for 25-49 year olds and 71% for 50-64 year olds.

[1] A01: Summary of labour market statistics, ONS (2021). Data taken from 23 March 2021 release. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/

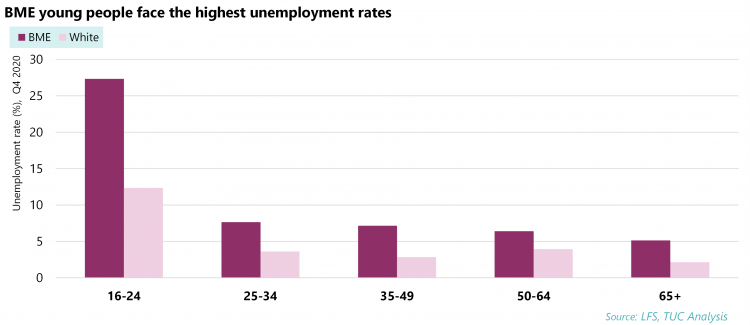

BME youth unemployment

Young workers from BME backgrounds have been particularly hard hit. The unemployment rate for young BME workers has reached 27.3% compared to 12.4% for young white workers[1]. This tells us that BME young people who choose to work, rather than study, have a more difficult time in the labour market than their white peers.

During the pandemic, the unemployment rate for BME young workers increased more than twice as fast as the unemployment rate for young white workers. The unemployment rate for BME young workers has risen from 18.2% to 27.3% between the final quarter of 2019 and the final quarter of 2020. This is a 50% increase in the rate, and a rise of 9 percentage points. Over the same period the unemployment rate for young white workers rose from 10.1% to 12.4% – an increase of 22% of the original rate, or 2.3 percentage points.

[1] Figures for BME youth unemployment are based on TUC analysis of the Q4 2020 Labour Force Survey, the most recent data available.

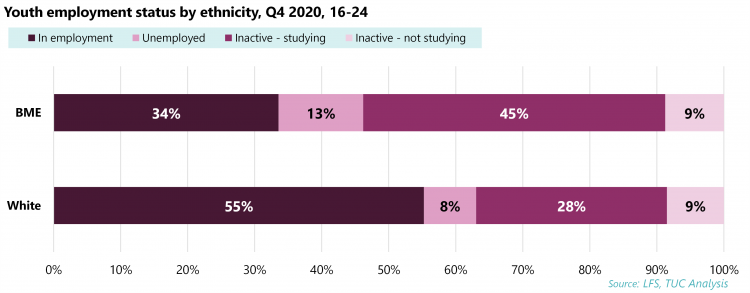

The above unemployment rates measure the proportion of young people who want to work but do not have a job. They do not include young people who are inactive such as students. Below we show how employment and education participation levels differ between BME and white young people aged 16-24. White young people are much more likely to be in employment, while BME young people are much more likely to be in education than their white peers.

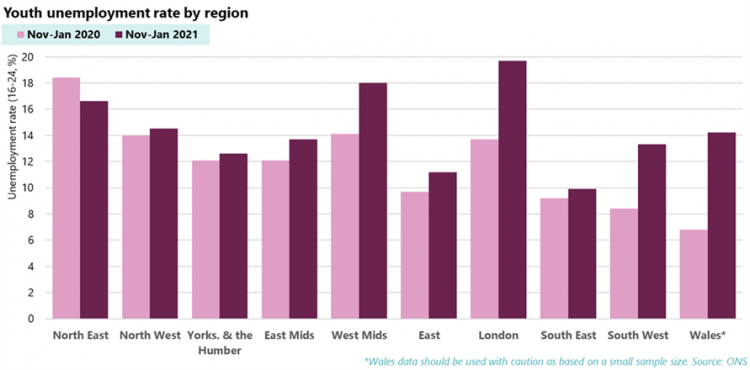

Regional youth employment

Across the pandemic, youth unemployment has risen in every region except one, the North East. Between Nov-Jan 2020 and Nov-Jan 2021, the largest rises in the youth unemployment rate[1] were in:

- The south west, a 58 percent rise from 8.4 per cent to 13.3 percent

- London, a 44 percent rise from 13.7 per cent to 19.7 percent

- West Midlands, a 28 percent rise from 14.1 per cent to 18 per cent

While the North East youth unemployment rate has fallen, the unemployment rate remains high at 16.6 percent.

[1] X02 Regional labour market: estimates of unemployment by age, ONS (2021). Data taken from 23 March 2021 release. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/

What we need to see change

Furlough

In the short-term, it’s vital that the furlough scheme is continued for as long as it’s needed. Young workers are more likely to be furloughed, and winding down and ending the scheme early puts their jobs at unnecessary risk. The government should act decisively now and create confidence by extending the scheme until the end of the year.

Universal Credit

For those who do lose their jobs, it’s vital that there’s a proper safety support net. Young workers who lose their jobs are left to rely on a cruel, ungenerous benefits system, especially as young workers are paid a lower standard payment.

The social security system should support those who do lose their jobs to stay on their feet rather than fall into hardship. Government must therefore:

- Raise the basic level of universal credit and legacy benefits, including jobs seekers allowance and employment and support allowance, to at least 80 per cent of the national living wage (£260 per week).

- End the five-week wait for first payment of universal credit by converting emergency payment loans to grants.

- Remove the savings rules in universal credit to allow more people to access it.

- Significantly increase child benefit payments and remove the two-child limit within universal credit and working tax credit.

- Ensure no-one loses out on any increases in social security by removing the arbitrary benefit cap. In addition, no one on legacy benefits should lose the protection of the managed transition to universal credit as part of this change.

- Scrap the no-recourse-to-public-funds rules that deny access to social security.

Job creation and Kickstart

It’s important that there are new jobs for young people who do lose work. We need to see the government investing now to help create jobs in the coming years. Research carried out for the TUC by Transition Economics reveals that fast tracking spending on projects such as broadband, green technology, transport and housing could deliver a 1.24 million jobs boost by 2022[1], and the TUC has set out plans to fill and create 600,000 jobs in the public sector[2].

Alongside this, we need to see big improvements to the Kickstart scheme. The scheme intended to create 250,000 jobs for young workers, but the scheme has so far seen only around 4,000 young people start placements[3]. Only 2% of private sector businesses currently plan to use the scheme[4]. The scheme clearly needs a revamp and an extension to ensure it helps young workers find new jobs.

The TUC has previously set out what is need to make the most from the Kickstart scheme , including:

- Good quality jobs with training built in – so there must be a guarantee that young people get access to real training – and strict checks to ensure employers are offering it.

- Additional jobs of real value to the community - there needs to be strict vetting of the new job placements, to make sure these are additional jobs.

- The programme must be based on equality from the start - the programme must be designed to actively work against any discrimination – with regular monitoring to make sure that everyone gets fair treatment.

- Employers should top up wages - the government is funding minimum wage jobs. But employers should do the decent thing and top up pay to a real living wage.

The government now need to go further. They should:

- Extend the scheme past its current planned cut off in December 2021 to help young people who will be made unemployed in the months ahead.

- Widen eligibility to the scheme. It should allow for earlier access to those young people not already claiming Universal Credit, such as those newly unemployed and those ineligible, including 16-17 year olds.

- Ensure that ethnicity monitoring is built into the scheme so it is clear who is taking part and whether they are getting jobs at the end.

- Encourage employers to use positive action measures permitted by the Equality Act.

- Establish national and regional recovery councils, working with the TUC and other stakeholders to ensure the opportunities are good quality and fit with priorities for the labour market.

Dedicated careers advice

Young people already face an uncertain future, which has been worsened during the pandemic. For young people coming out of work during the crisis, or those newly-entering the labour market, plans for the future will require support.

Over the years, funding for professional, independent careers advice for young people has been cut. Much of the support available is via the charitable and voluntary sector.

The government should invest in dedicated careers advice services, accessible to all young people. This would allow for:

- Careers advice linked to local labour market needs or where there are skills shortages

- Support for young people accessing training and skills needed to progress careers or transition to new opportunities as part of a move towards net-zero and jobs of the future

- Help young people better understand the opportunities available to them, increasing awareness of apprenticeships, further and higher education or other job opportunities

Read all the issues in the Jobs and Recession series

Related reports:

-

Jobs and Recovery Monitor - issue 1

-

Jobs and Recovery Monitor - BME workers - issue 3

-

Jobs and Recovery Monitor - Regions - issue 4

-

Jobs and Recovery Monitor - update on young workers - Issue 5

[1] Rebuilding after recession: a plan for jobs, TUC (2020). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/rebuilding-after-recession-plan-jobs

[2] A plan for public service jobs to help prevent mass unemployment, TUC (2020). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/plan-public-service-jobs-help-prevent-mass-unemployment

[3] Hansard (2021). Therese Coffey’s contribution to debate on Kickstart: Employer Accessibility on 8 March 2021. Available at: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2021-03-08/debates/FE1D15E8-2429-41BC-93E3-B25C7732FCD2//a>

[4] Business insights and impact on the UK economy, ONS (2021). Data taken from BICS Wave 26: 25 March 2021. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/economicoutputandproductivity/output/datasets/

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox