A plan for public service jobs to help prevent mass unemployment

The coronavirus pandemic, a health crisis, has presented the biggest economic shock in decades. Trade unions supported the lockdown of the economy as the right thing to do. But as we emerge, there is a growing danger that the pandemic will give way to an unemployment crisis.

Already too many workers have confronted the loss of work, and others face massive uncertainty and anxiety about the future.

Government needs to do everything it can to protect jobs. But it also needs to invest now in the work the country needs to get through the crisis, and to create the jobs needed to prevent mass unemployment and severe recession.

The TUC set out a plan in June for how we could create 1.24 million jobs in the next two years in the green industries of the future. But government investment needs to go beyond that: we need a plan for direct public sector job creation.

A public sector jobs drive will create decent, higher skilled and better paid work, and can help tackle the persistent race, class, gender, disability, regional and wider inequalities the UK has faced for decades.

We are calling for government to invest in 600,000 jobs in public services, including

- 135,000 in health

- 220,000 in adult social care

- 110,000 in local government

- 80,000 in education.

- 50,000 in civil service / public administration

Overall, the TUC’s plan for jobs would deliver 1.85 million new jobs in the next two years.

1. The jobs crisis and the threat of mass unemployment

The latest figures show employment falling by 220,000 between the first and second quarters of the year, the steepest quarterly fall since the peak of the global recession in 2009. These losses are so far concentrated in older and younger groups. More-timely payroll information shows employee jobs shrinking by a total of 740,000 between January and July.

The UK was already facing a crisis of insecure work. TUC analysis shows that 3.6 million people, one worker in nine, were in insecure work ahead of the coronavirus outbreak:

- 840,000 on zero-hours contract workers

- 970,000 in other types of insecure work - including agency, casual, seasonal and other workers and

- 1,810,000 in low-paid self-employed

In total this means 5 million workers were unemployed or in insecure work1. At the time we warned these workers were exposed to massive drops in income or unsafe working conditions when the pandemic hit. And we already know that a sharp increase has meant the number of people employed on Zero Hours Contracts is above one million for the first time, including many working in essential roles in retail and social care.2

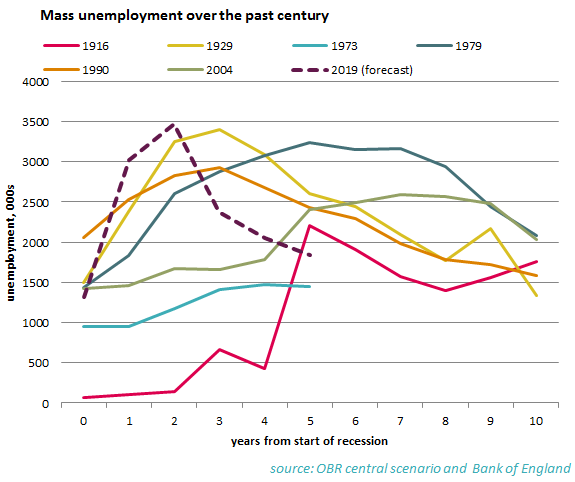

Looking ahead, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) project unemployment rising to a total of between 3.3 and 4.5 million, an increase of 2 to 3 million from the present level at 1.3 million. The chart below compares their ‘central scenario’ with episodes of mass unemployment over the past 100 years.

The scenario is striking over this and next year for the most rapid and severe increase in unemployment over the last century. And while the OBR predict a rapid improvement relative to previous episodes, the TUC are concerned this scenario is too optimistic. The Bank of England has shown that on average, employment takes around seven years to return to its previous level.[1]

Activity in the economy as a whole is still greatly reduced. The quarter two UK GDP decline of 20.4% was the worst of all OECD countries where information is currently available (and double the average of 9.9%). Monthly figures show that activity has rebounded since April, but remains 11.7% below the levels seen in February 2020, before the full impact of the coronavirus pandemic. The most substantial recovery (through to July) is in retailing activity, but here the strongest gains are in online sales and the Bank of England have warned that the “initial sharp recovery might have reflected some pent-up demand, with spending falling back a little recently”.[2]

Allowing unemployment to rise will create a vicious circle: reduced consumer spending power will weaken the economy, raising the risk of further unemployment. We know that the private sector cannot address this alone. The TUC is therefore calling on the government to use the levers at its disposal and create the jobs we need in the public sector to deliver the public services of the future. This will give opportunities to those who lose work and those entering the jobs market for the first time, and also help to offer an alternative to those trapped in insecure work.

A plan for public service jobs

Public sector workers have gone above and beyond to keep essential services going during the crisis. But they went into the crisis in a weakened position following a decade of cuts and the pandemic is putting our already struggling public services under even more strain. Even in priority areas spending has fallen well short of need, and the pandemic has further exposed serious shortfalls in provision and staffing. Yet the pandemic has confirmed that the safety and security of society relies on strong and resilient public services – and that means public services that are properly staffed. A recruitment drive across the whole of the public sector is urgently needed, with a parallel commitment to improve conditions. Any existing redundancy programmes should be halted with immediate effect.

135,000 jobs in the National Health Service

The NHS has operated short-staffed on the front line of the pandemic, with a 10,000 annual shortfall in nursing applications and progress going backwards against GP recruitment targets.[3] The Nuffield Foundation report current vacancies of 100,000 likely rising to 250,000 by 2030.[4]

Government should:

- Fill immediate hospital vacancies of 100,000, including 40,000 nursing vacancies.

- Pre-empt 1/5 of future vacancies with an additional 30,000.

- Recruit 5,000 GPs.

Attracting sufficient numbers to the healthcare professions is a significant challenge. Numbers applying to study nursing, for example, have still not recovered to 2016 levels, before the NHS bursary was scrapped and tuition fees introduced for healthcare students in England. The government announced in December 2019 that maintenance grants will be reintroduced for healthcare students in England from September 2020, but these are only half what students in Scotland are set to receive and tuition fees will still have to be paid. We need action on maintenance grants and tuition fees for healthcare students in England to attract more healthcare professionals to the sector.

Recruitment will also require more focus on supporting staff, including meaningful action on equality and inclusion, building on existing initiatives, so that all NHS organisations have concrete action plans to tackle discrimination and inequality. Noting pay and reward are tangible signs of how far staff are valued and have a clear impact on retention, after the current Agenda for Change pay deal which runs until 2021, pay in the NHS will need to continue to rise in real terms in line with wider economy earnings.[5]

220,000 jobs fixing Social Care

Above all the pandemic has exposed the disarray in adult social care provision. The Institute for Government report 120,000 vacancies in social care at any one time, and Skills for Care project an additional 580,000 to 800,000 jobs will be required by 2035 to meet the increases in demand.[1]

Government should:

- Recruit 120,000 to meet immediate need and 100,000 towards longer-term need.

To support this step change in the provision of adult social care the TUC are calling for a national bargaining body, equivalent to the NHS Social Partnership Forum, ensuring staff, employer and regulator perspectives on policy implementation and implications can be discussed, and good practice is developed.

This body should:

- develop and negotiate a sectoral workforce strategy that supports standards, productivity and workforce development

- agree a national framework for formal skills accreditation, linked to a transparent pay and grading structure at NJC or Agenda for Change level, with a professional CPD package which offers training, development and job evaluation to support genuine career progression, recognition and reward.

Beyond these institutional changes, the government’s proposed Immigration Bill should be scrapped.

110,000 jobs in local government

Local government is in crisis, with cuts severely damaging the day-to-day public services relied upon by millions of families. Even ahead of the pandemic local authority leaders spelled out these dangers to front-line services and the likelihood of failing to fulfil statutory duties. According to research by UNISON, the workforce has fallen by 240,000 (25 per cent) since 2010, of which 108,000 were redundancies and the rest outsourced to the private sector. The research showed hits of roughly equal size to education, environmental services and social care, with only housing services having a smaller reduction. [2]

Government should:

- Provide funding to bring back 108,000 local government jobs.

80,000 jobs in education

Over the past five years per pupil funding has been cut by 8 per cent in real terms, and the number of teachers has fallen by 3,500. Over the same period, the number of pupils in state primary, secondary and special schools has increased by 315,000.[3]

Education specialists have warned of a recruitment shortfall of 5,000 teaching posts a year, exacerbating rising pupil teacher ratios. As schools return in the wake of the pandemic, greatly reduced not increased ratios are essential and a massive jobs drive is necessary.

Government should:

- Recruit an extra 20,000 teachers to restore secondary pupil teacher ratio to the level of 15.0 in the early 2010s from 16.6 now.[4]

- Recruit an extra 20,000 teachers to begin improving the primary (and nursery) pupil-teacher ratio from 20.9 towards the OECD average of 15.0.[5]

- Recruit an extra 40,000 support staff alongside newly recruited teachers, to aid handling the unprecedented classroom environment in the future.

Under the 'Fund the Future' campaign the University and College Union are calling for no cuts to funding and staffing in higher education and further education[6]. A report by London Economics highlighted a potential £2.5bn loss of income from tuition fees and teaching grants for UK universities as a result of the coronavirus. Without government intervention, an estimated 30,000 jobs in higher education are at risk, with a further 32,000 jobs under threat throughout the wider economy. The total economic cost to the country from the reduced economic activity generated by universities alone - due to the loss in income - is estimated at more than £6bn.

Government should:

- protect the 30,000 jobs in higher education at risk from the coronavirus.

50,000 jobs in the Civil Service

The government should halt all planned public sector redundancies and outsourcing programmes. In the cases where the pandemic means unavoidable job losses, work should be guaranteed in other departments. The civil service will be on the front line to support the public in a jobs crisis, and will need resources to meet these challenges. Immediate action is needed across the following programmes, though this is far from exhaustive:

- 6,500 Ministry of Justice redundancies should be halted.[1]

- Recruit 4,000 new prison officers to address severe understaffing and overcrowding in our prisons, which is leading to more incidences of self-harm and suicide among prisoners.[2]

- 30,000 new posts in the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) to help the Universal Credit system meet the extra demands from rising unemployment. Over the past decade employment at the DWP fell from a peak of 130,000 in 2011 to 78,000 staff today, a loss of 52,000 jobs in less than a decade. A senior DWP manager has advised PCS that to maintain the extra claims they have had going forward, re-introducing Work Coach activity and ongoing maintenance will need around 31,000 extra staff.

- Halt 2,000 redundancies in HMRC.[3]

- HMRC customs jobs should be expanded to support the customs challenges under Brexit: currently the government is failing to recruit even to a target that falls far short of need, having recruited only 900 of 1,300 posts when 5,000 posts are needed.[4]

- Halt around 1,000 job losses across DCMS redundancy programme and the Tate and Southbank Centre, increasing grants as necessary.[5]

A large-scale investment programme aiming towards net zero

In addition to the public sector jobs drive, government should invest to create the jobs we need in the industries that will help us reach our net zero carbon target. Research for the TUC by Transition Economics looked at projects according to their ability to create jobs quickly, help the transition to net-zero, and improve skills and productivity across the UK. They showed that fast tracking an £85bn investment programme could create 1.24 million jobs over the next two years[6]. The projects include:

- 40,000 new jobs from investment in high-speed broadband

- research and development in de-carbonising technology for manufacturing could help create over 38,000 new jobs

- 120,000 jobs in expanding and upgrading the rail network

- investing in 59,000 jobs on the electrification of transport, including electric buses, new electric ferries, battery factories, and electric charging points

- 500,000 jobs building new social housing and retrofitting existing social housing

Other projects could also make a significant difference. Early works, for example earth works and transport links for major infrastructure projects, such as new nuclear, would give a good jobs boost in specific areas of the country. Industry estimates suggest that getting going on large Gigawatt new build nuclear would provide around 20,000 construction jobs as well as supporting jobs in the wider economy, for example in steel manufacturing.

These initiatives should be deployed and operated strategically, under a National Recovery Council (NRC) with membership drawn from trade unions, employers, government and associated infrastructure to operate at both national and regional levels.

The NRC should work alongside a new Just Transition Commission to oversee the transition to net-zero in a way that supports jobs and workers across the UK. Procurement from the private sector should be used to support UK jobs by working strategically with commissioners and both current and potential providers (i) to map goods and service requirements and identify procurement opportunities in advance (ii) build capacity to bid and deliver through the supply chain and (iii) use intelligent, social value procurement to secure employment, labour standards, skills and environmental outcomes. An Olympics-style plan to promote good quality jobs and training on every new infrastructure project should be set out, specifying how these projects will help deliver on a Jobs Guarantee.

Building equality into these plans

The UK labour market is already marked by persistent inequalities that leave those with protected characteristics, including women, BME groups, disabled people and LGBT+ people facing structural discrimination. To take just some examples:

- Black workers, women and disabled workers are all overrepresented in insecure work, with 1 in 24 BME workers on zero-hours contracts, compared to 1 in 42 white workers.

- These groups also face persistent pay gaps: the gender pay gap remains stubbornly high at 17 per cent, and disabled workers still face a pay gap of over 15 per cent.

- Discrimination still forces groups facing protected characteristics into more difficult and dangerous roles. 54,000 women a year are, for example, forced out of work due to pregnancy and maternity discrimination. Our report ‘Is Racism Real’ revealed that despite experiencing high levels of discrimination, BME staff do not feel confident in reporting racism at work, with almost half not reporting incidents.[7]

- Harassment in the workplace often marks the experience of groups with protected characteristics; TUC research found that seven in ten LGBT people had experienced some form of sexual harassment at work, alongside over half of all women.

Previous recessions have often served to exacerbate these inequalities, with those in low paid insecure roles being first to lose work, and structural discrimination holding back their chances of finding a new job. BME groups faced higher unemployment in the 2008-09 recession, and still high unemployment rates. Research shows that during upturns disabled people are the last to gain employment, and during downturns they are first to be made unemployed.

The government must set out a plan for how it will ensure that job creation helps to tackle discrimination and inequality, and how it will meet its duties under the public sector equality act.

1. Protecting work and strengthening the safety net

Creating jobs will be a vital part of the recovery. But government must also ensure that as many jobs are protected as possible, and that those who do lose work have a real safety net to help them back on their feet.

Protecting jobs

The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS), argued for by unions, has done vital work protecting jobs. The scheme has supported 9.6 million people in total, with over 6.8 million people still supported by the scheme at the end of June.[1] And while too many people have missed out, the Self Employment Income Support Scheme has also supported many people’s livelihoods.

But with the schemes coming to an end in October, and the threat of mass unemployment still with us, Government needs to do more to support jobs, learning from experience across Europe. This support should come with strings attached. We have an opportunity to use this moment to upskill our workforce, prepare for the jobs of the future, and build a fairer labour market that offers decent work to everyone.

The TUC has set out a proposal for a Job Protection and Upskilling plan that would:

- Support businesses to bring people back to work and save jobs, by providing support where workers are working at least a minimum proportion of their normal working time

- Develop the skills of the future, by ensuring any worker undertaking less than 50 per cent of their normal working time has access to quality funded training; and

- Require businesses receiving support to; set out fair pay plans to ensure that government support is helping develop decent jobs; pay their tax in the UK; not to pay dividends while using the scheme; to allow trade unions to access the workplace and pledge to eliminate the use of Zero Hours Contracts.

Similar support must also be put in place for the self-employed, including those who have missed out from previous schemes. Support in both cases would be targeted at those businesses who can show that their trading continues to be impacted by coronavirus restrictions.

Workers eligible for the plan would continue to receive 80 per cent of their normal wages in non-working time, up to £2,500 a month, with those on the minimum wage receiving full wage protection. Businesses would receive a subsidy from government of 70 per cent for each non-working hour. [2]

Support for those who lose work

Government must invest in the training people need, and in decent social security to help everyone who does lose work to get back on their feet. They should:

- introduce a new right to retrain for everybody, backed up by funding and personal lifelong learning accounts. This should involve bringing forward the £600m promised investment in a national skills fund, and accelerating the work of the national retraining partnership to ensure there is a gateway to new skills for everyone.

- Offer an education and training guarantee for all school leavers and other young people aged 25 and under who wish to take up this option. This guarantee would include an apprenticeship, place at university or college, and other education and training options. In support of this, the apprenticeship levy should be flexed to allow employers to use their funds to also provide pre-apprenticeship training programmes where appropriate.

- Invest in rapid redundancy support for everyone at risk of losing their job, with companies required to notify regional recovery panels when they are consulting on redundancies, and jobcentre plus organising tailored on-site provision to offer rapid access to training and other support.

- Raise the basic level of universal credit and legacy benefits, including jobs seekers allowance and employment and support allowance, to at least 80 per cent of the national living wage (£260 per week).

- End the five-week wait for first payment of universal credit by converting emergency payment loans to grants.

- Remove the savings rules in universal credit to allow more people to access it.

- Significantly increase child benefit payments and remove the two-child limit within universal credit and working tax credit.

- Ensure no-one loses out on any increases in social security by removing the arbitrary benefit cap. In addition, no one on legacy benefits should lose the protection of the managed transition to universal credit as part of this change.

- Introduce a wider package of support for households, by introducing a fully funded council tax freeze, significantly increasing the hardship fund delivered by local authorities and moving swiftly to introduce a permanent fund that provides a permanent source of grants to support those facing hardship. Government must also increase the support it provides to renters.

- Scrap the no-recourse-to-public-funds rules that deny working families’ access to social security.

6. Putting jobs first is the best protection for the economy

Putting people to work in the public sector supports spending in the economy and revives private sector activity. Government spending on a jobs’ drive will be recouped by higher government revenues as the economy recovers. The jobs’ drive outlined in this report looks only at the employment directly created by government, it does not include additional (secondary) employment as the economy revives.

The difference between the OBR best and worse-case scenarios is additional unemployment of 2 million. According to their projections, government revenues would be £80bn lower in 2020-21 and £125 billion lower in 2021-22. Using standard average costings, the cost of increased public sector employment should not exceed £20 billion.[3] This might be phased in over two years so that the costs in the first year were £10bn and then £20bn in the second year. The investment programme for green jobs has already been costed at £85bn over two years, perhaps £30bn followed by £55bn. The total annual costs of £40bn and £75bn of the jobs drive falls well below the increased costs of the worst-case scenario. Given the increased employment would help ensure that the worst case scenario did not happen, the UK public finances would be in better shape as a result of the jobs drive.

These are conservative estimates. A jobs drive would also lead to multiplier effects as the economy was strengthened, and would mean higher taxes and lower benefit expenditures. These effects in their own right could offset a good part of the costs of the jobs drive, as well as restore confidence across the economy as a whole. Inaction would not only fail the needs of society but would be a false economy in terms of the public finances.

The lesson of the UK’s economic history is that investment is the most effective way to deliver growth following a recession, and to restore the public finances. We failed to learn this lesson in 2010 with devastating results. This time must be different.

The approach outlined in this report is aimed first at supporting workers and businesses in the transition from lockdown. But designed right, it can help address some of the UK’s biggest challenges – the need to reach a net zero-carbon economy; address persistent race, class, gender, disability regional and wider inequalities; and deliver a higher skill and higher paid, more productive economy.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-august-2020/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-august-2020

[2] Further details of the scheme are set out at TUC (2020) A new jobs protection and upskilling plan at https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/new-jobs-protection-and-upskilling-plan

[3] Ready reckoner from IFS (2019) ’Public sector pay and employment: where are we now?’: in 2018-19 the public sector paybill including employer pension and NI contributions was £190 billion for 5.3m jobs. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/BN263-public-sector-pay-and-employment1.pdf

[1] https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-08/Insecurework%20repor…">https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-08/Insecurework%20repor…

[2] https://tribunemag.co.uk/2020/08/instead-of-rewarding-key-workers-brita…">https://tribunemag.co.uk/2020/08/instead-of-rewarding-key-workers-brita…

[1] https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/law/union-hits-out-as-courts-shakeup-threatens-6500-jobs/5065951.article

[2] Institute for Government report government undoing only 2,500 of 6,609 job cuts at https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/performance-tracker-2019/prisons

[3] https://www.pcs.org.uk/pcs-in-hm-revenue-and-customs-group/latest-news/redundancies-update-timetable-revealed

[4] As previously called for by the TUC: https://www.tuc.org.uk/blogs/we-need-5000-extra-customs-officers-cope-brexit-more-cuts-are-coming-instead

[5] See PCS press statements:

[6] The full proposals are set out in TUC (2020) ‘Rebuilding after Recession: a plan for jobs’ at

https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/rebuilding-after-recession-plan-jobs

[7] https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Is%20Racism%20Real.pdf

[1] The Size and structure of the adult social care sector and workforce in England, 2019 at https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/Size-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/Size-and-Structure-2019.pdf

[2] ‘Around 25% of local government jobs ‘slashed’ due to austerity’ at https://www.localgov.co.uk/Around-25-of-local-government-jobs-slashed-due-to-austerity/47647; the research was based on data obtained under freedom of information from all local authorities.

[3] https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-09/SpendingReviewSubmission.pdf

[4] Department for Education, School Workforce in England, June 2019 at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/811622/SWFC_MainText.pdf

[5] See OECD, ‘key insights’ at https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/#!node=41720&filter=all

[6] https://www.ucu.org.uk/article/10831/UCU-launches-Fund-the-Future-campaign-to-secure-universities-and-colleges

[1] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/monetary-policy-report/2020/august/monetary-policy-report-august-2020.pdf?la=en&hash=75D62D3B4C23A8D30D94F9B79FC47249000422FE

[1] https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Is%20Racism%20Real.pdf

[2] Monetary Policy Report, August 2020, p. 27

[3] Institute for Government, Performance Tracker 2019 at https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/performance-tracker-2019_0.pdf

[4] Nuffield Foundation, ‘Staffing shortfall of almost 250,000 by 2030 is major risk to NHS Long Term Plan, experts warn’ at https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/news-item/staffing-shortfall-of-almost-250-000-by-2030-is-major-risk-to-nhs-long-term-plan-experts-warn

[5] ‘Closing the gap’, March 2019 at https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-03/closing-the-ga…

[1] Ready reckoner from IFS (2019) ’Public sector pay and employment: where are we now?’: in 2018-19 the public sector paybill including employer pension and NI contributions was £190 billion for 5.3m jobs. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/BN263-public-sector-pay-and-employment1.pdf

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox