Soaring insolvency rates the latest symptom of Britain’s broken economy

Individual insolvencies have drastically risen over the past year as the UK’s household debt crisis continues to grow.

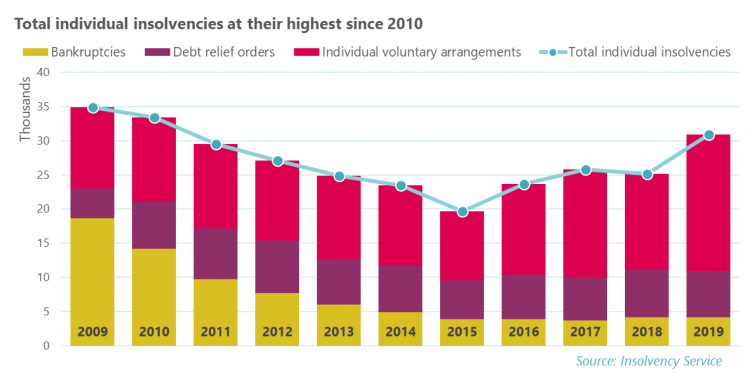

In the third quarter of 2019, there was a total of just under 31,000 individual insolvencies – a 23 per cent increase on the same period last year.

In total there have been over 93,000 insolvencies in 2019, which is the highest level at this point of the year since 2010.

Mushrooming insolvency rates are the latest sign that the UK’s economy is broken. That’s why this election must deliver real change for working people.

What is insolvency?

An insolvency occurs when someone is unable to keep up with debt repayments.

When someone becomes insolvent in England and Wales, they have three options: bankruptcy, an individual voluntary arrangement (IVA) or a debt relief order.

It’s the second of these, IVAs, that’s driving the recent rise in insolvencies. The below chart shows the total number of individual insolvencies, as well as the form of insolvency.

Back to pre-recession levels

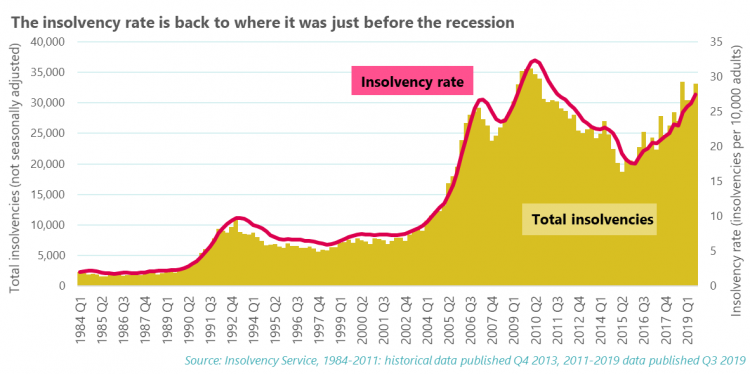

The insolvency rate (the number of insolvencies per 10,000 adults) is currently 27.5. That’s a rate we haven’t seen since the lead up to the financial crisis, as we can see from the chart below.

There’s both a gender gap and regional differences in the insolvency rate .

Since 2014, the insolvency rate has been higher among women. And on a regional level, the insolvency rate in North East England is over double the rate in London.

Local authority level data shows that the insolvency rates in areas such as Stoke-on-Trent, Scarborough, Torbay and Plymouth are four to five times as high as the local authority with the lowest rate.

Tip of the iceberg

No form of insolvency is taken lightly. Insolvency has serious implications, such as restricting access to credit and placing the person on the Insolvency Register, potentially affecting jobs and housing. They’re used as a last resort when debt has got too much to manage.

The insolvency statistics above are therefore the tip of the iceberg. We know that household debt is currently at a record high. The latest figures show that unsecured debt per household is currently £14,200, 28% higher than it was in the same period of 2008.

We also know from research we released earlier this year that many more people than this are struggling with debt. Over half of households (53%) report having some form of unsecured debt, most commonly in the form of credit card debt (60%), overdrafts (28%), personal loans (25%) and car finance (25%). Not all of these will lead to an insolvency.

For some people, debt is manageable. But the majority of households with unsecured debt (61%) describe repayments as a burden, with one-fifth saying they’re a ‘heavy’ burden. Given the percentage of those with unsecured debt, this means that the finances of one in every ten households are heavily burdened by debt repayments. Many working people are also on the edge of falling into debt due to a lack of savings. When we polled working people earlier this year , two-fifths (41%) of workers told us that pay not keeping up with living costs is among their biggest concerns at work. Nearly 1 in 3 (30%) workers said they wouldn’t be able to pay an unexpected £500 bill – up from 24% in 2017. And of those that could pay, a quarter (24%) say they would have to go into debt or sell something.

The real wage squeeze

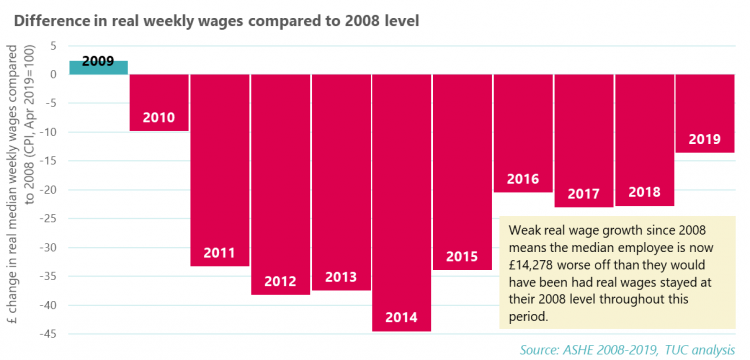

The burgeoning debt crisis takes place against the backdrop of a decade-long real wage squeeze. Real wages still haven’t recovered from the recession, with median weekly wages remaining £14 per week below where they were in 2008.

The chart below compares real weekly median earnings in each year to what they were in 2008. It shows that in every year except 2009, wages were lower than they were in 2008.

This has a cumulative impact, and means the median worker is now, in total, around £14,200 worse off than they would have been had they been earning 2008 real wages throughout this period.

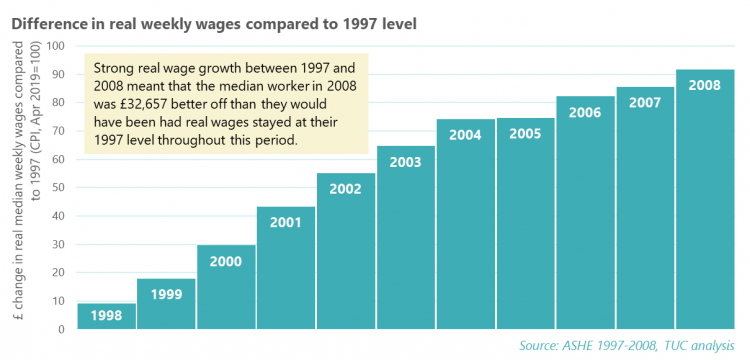

The full impact of this can be seen if we compare this period since 2008, to the 11 years before 2008.

The chart below shows how real median weekly wages in each year compared to 1997. In each year they were higher, with the median employee earning over £90 per week more in 2008 than they were in 1997.

This strong real wage growth meant that the median employee was, in total, around £32,657 better off in 2008 than they would have been had they earnt 1997 real wages throughout this period.

A broken economy

Given the record high levels of household debt, and the on-going real wage crisis, it’s little surprise that the debt relief charity StepChange has reported that the first six months of 2019 was their busiest ever start to the year, with one new client every 48 seconds .

It’s also no coincidence that, at the same time, the foodbank charity Trussell Trust report that the financial year 2018/19 was its busiest ever year – handing out a record 1.6 million packages of three-day emergency food supplies. The main reasons for referral were ‘income not covering essential costs’, ‘benefit delays’, and ‘benefit changes’.

Record levels of debt, growing insolvencies, an increased reliance on foodbanks, and record levels of in-work poverty are all symptoms of the same problems: a real wage crisis, a decade of government-imposed austerity, and an economy that just isn’t working for too many people.

Time for change

Millions of working people are still feeling the effects of the recession in their day-to-day lives. That’s why we need fundamental change to help those bearing the brunt of 11 years of recession, austerity and stagnant wages.

The first thing we can do is to raise the minimum wage to £10 per hour to ensure that everyone is paid enough to live on.

We also need to ban zero-hours contracts and crack down on low-paid insecure work, both of which mean working people don’t know how much they’ll earn from one week to the next.

And we need to scrap Universal Credit, a cruel reform to the benefits system that has pushed people into debt and poverty .

This is why the upcoming election is so important: we need fundamental change to build an economy that works for working-class families.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox