Can Britain do better? The case for borrowing to invest

Real wages are not set to return to their pre-crisis levels until 2025 (according to a projection by the Resolution Foundation). Spending on public services per person will now be cut for 13 years in a row, falling by over £900 a year (nearly 20%) between 2009-10 and 2022-23 (see our Budget summary). And our economic growth over the next six years is set to average 1.4%: half the longer-term, pre-crisis average of 2.8%.

The deep cuts to public services are still justified as necessary to repair the public finances. As George Osborne pleaded in 2016 ahead of the referendum “The British people have worked so hard to get our country back on track”. But this goal too is receding ever further into the distance: the OBR no longer expect the deficit to be cleared up even by 2022-23 – seven years after the original 2016-17 target.

Could Britain do better with an alternative strategy? The Chancellor set out one answer in his budget speech: “The key to raising the wages of British workers is raising investment – public and private”. But to date, investment spending has been constrained by a reluctance to borrow in order to invest – despite widespread evidence that this would be the most effective way to turn around Britain’s economic performance now.

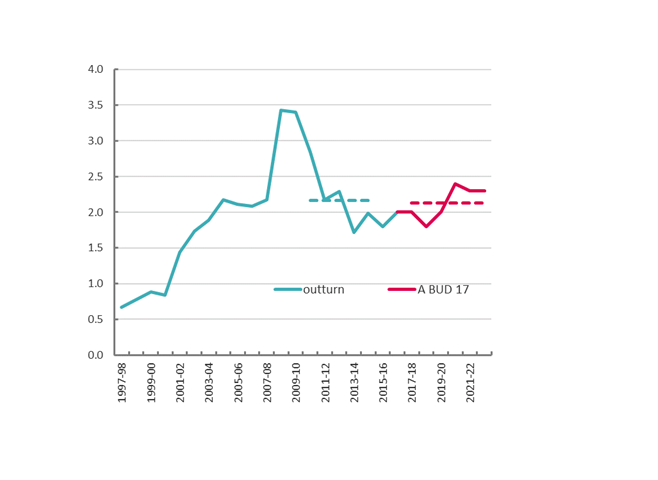

The Chancellor took one small step to putting his money behind his statement last week, boosting investment by £7bn over the current parliament. But there is always an air of ‘jam tomorrow’ about the Treasury’s approach to investment spending. To date, the average spending of 2.13% across the current parliament as a whole is still below the average of 2.17% in the last parliament – hardly a high bar (see chart).

Public sector net investment, % GDP

The scale of the investment also needs to be put into international context. The average spend across the OECD on investment is 3.5 per cent of GDP (the figures for international comparisons tend to be based on gross investment, while the previous figures were net of write-offs).

The Chancellor’s new announcements get us to just 2.9% of GDP (in 2020 and 2021) – only a notch up from 2.6% in 2016 – and it’s back down to 2.8% in 2022. It’s no surprise that the OBR described the boost to growth provided by this as ‘modest’.

Public sector net investment in OECD countries, % GDP

Bringing the UK up to the OECD average would cost around £19bn in today’s prices.

What would be the impact of this on the public debt?

In 2016, the OECD looked in detail at this question. In ‘Using the fiscal levers to escape the low growth trap’ they argue that the impact of this kind of investment spending at a time when interest rates are at record lows can reduce the public debt ratio:

To the extent that monetary policy is constrained [that is, it is hard to cut interest rates further because they are already near zero], an investment-led stimulus may raise output more than it increases debt, leading to a fall in the debt-to-GDP ratio in the short term. This will likely be the case if public investment manages to catalyse private investment.

It’s worth spelling out how this works. One way to do this is to think of an individual firm. If it wants to expand, it borrows on the basis of future earnings that any increased investment will permit. The loan will be repaid by higher revenues in the future. The same is true of government, but in more ways than one.

Any new government spending will immediately create new work and higher wages, these will be spent into the economy giving stimulus to other private sector companies. The new spending and incomes will strengthen the economy, create tax revenues and reduce the welfare bill.

These processes are captured technically by the idea of the multiplier (see here). At the moment, the OBR put the scale of the multiplier at less than one. But international institutions suggest that this is a very conservative estimate. In 2012 the IMF argued that the multiplier was between 0.9 and 1.7. And the US National Bureau of Economic Research find a multiplier between 1.7 and 2.0.

As the economy is strengthened, the public finances will be strengthened. If the government’s current policy has taught us anything, it is how this process works in reverse. Spending cuts have weakened the economy and reduced taxes and increased the welfare bill so that the public finances have not been repaired.

There is a need for lending as a bridge between the higher spending and the strengthened economy. (Technically it is the distinction between a loan as an input to policy and the deficit as an outcome of policy – see here.) And there are a multitude of ways of arranging any such financing. Most obviously there is no shortfall in demand for UK government bonds. Just as with firms, willing borrowers should be queuing up. If the financial system refuses to lend to strengthen the economy, then it’s not the right financial system.

We have tried and failed to resolve the public finances by retrenchment. The dismal outlook must mean that it is now time to try the opposite course.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox