Older workers after the pandemic: creating an inclusive labour market

There has been a significant increase in the number of older workers leaving the labour market before they reach state pension age. The number of people aged 50-65 who were not actively looking for work increased by over 200,000 between the third quarters of 2019 and 2021.

This has been driven by an increase in the numbers leaving because of long-term health conditions, and an increase in the numbers retiring from paid work. It has reversed long-term trends that have seen men and women extend their working lives over the last 25 years, and is damaging for both older people who are at increased risk of having to rely on inadequate working age benefits, and the wider economy which is experiencing skills and labour shortages.

Ensuring that older workers can participate in the labour market will require major changes in the workplace to ensure that older workers have the skills they need and that jobs and workplaces meet the needs of an ageing workforce. And making sure that those who are unable to continue working into their mid-sixties are not penalised as a result will require an overhaul of working and pension age benefits.

Black and ethnic minority (BME) and working class workers are significantly more likely to be forced out of work before they can access their state pension. So, improving jobs for these groups of workers as they age will be key to tackling labour shortages and reducing poverty in later life and retirement.

While BME workers are less likely to retire early than their white counterparts, those that do leave the labour market early are significantly more likely to do so because of poor health, and more than twice as likely to do so because of caring responsibilities. Just 17 percent of BME people who are economically inactive aged 50-65 have retired, compared to 40 percent of economically inactive white people, reflecting a wide ethnicity gap in average pension wealth.

People in low paid and manually intensive jobs are also at far greater risk of being forced out of the labour market early. Those working with heavy machinery and in ‘elementary occupations’ like cleaning or security are particularly vulnerable, closely followed by people in caring and other service occupations and retail and customer service.

Together these occupations account for just three in ten jobs in the labour market, but almost six in ten people who leave the labour market come from these sectors.

So, plans to tackle labour shortages by helping more older people stay in work must tackle the structural discrimination that means workers on lower pay are more likely to be pushed out.

This includes:

- Ensuring that, as we emerge from the pandemic phase of Covid, workplaces are safe for all workers through improved health and safety guidance and stronger enforcement, and bringing unions and employers together do ensure that we address workers and skills shortages and deliver the government’s ambition of a high wage, high productivity economy.

- Ensuring older workers have the skills needed to thrive in the labour market by giving them a right to a mid-life career and skills review and right to access funded retraining, and providing tailored support for older workers at risk of long-term unemployment or falling out of the labour market.

- Helping older workers to manage disabilities and health conditions by ensuring that employers put in place reasonable adjustments for disabled workers and tackling workplace discrimination, and strengthening flexible working rights to allow older workers to manage workloads.

- Reforming the state pension and benefits system so that people of all ages who are unable to work can maintain a decent standard of living, and tackle the issues that affect older workers most acutely. As well as de-coupling the eligibility age for pension credit from the state pension age and giving early state pension access to some people, this means shelving planned state pension age increases in response to stalling longevity improvements and growing longevity and labour market inequalities.

Older workers after the pandemic: creating an inclusive labour market

Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic we have seen rising levels of economic inactivity in the UK labour market. While support for the labour market such as the furlough scheme has avoided a steep increase in unemployment, since the first quarter of 2020 the headline figures show an additional 300,000 people aged 16-64 are now economically inactive according to the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics. This category covers those who are not actively looking for work, or are unavailable to start work and includes students, the long-term sick or disabled, carers and retired people. Inactivity has risen in previous recessions, but the numbers are still striking at a time when many employers are reporting a shortage of workers.

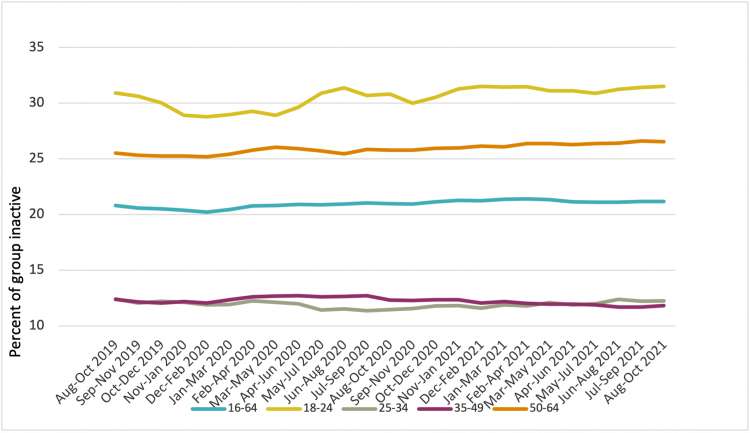

This rise in economic inactivity since the first quarter of 2020 represents a 0.8 percentage point increase and has been primarily driven by a growing number of workers under 24 and over 50 either leaving or delaying entering the labour market (see figure 1). Since the start of 2020, the economic inactivity rate of people aged 18-24 has risen by 1.6 percentage points, an increase of 47,000 while for those aged 50-64, it has risen by 1.5 percentage points, an increase of 228,000 (reflecting the larger size of this group of workers).

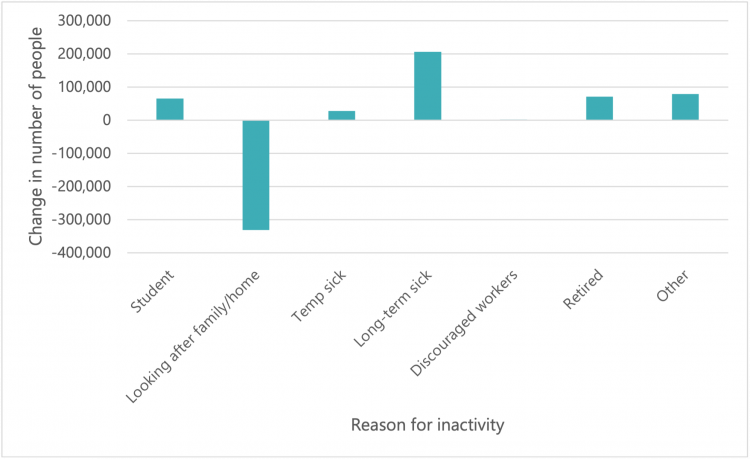

Across all people aged 16-64, the increase is the result of higher numbers of students, long-term sick and retired people, partly offset by a sharp drop in the number of people economically inactive because of caring responsibilities (see figure 2). Between the third quarters of 2019 and 2021 the number of people unable to work because of long-term health problems increased by more than 200,000, while the number of students and retired people increase by over 65,000 and over 70,000 respectively.

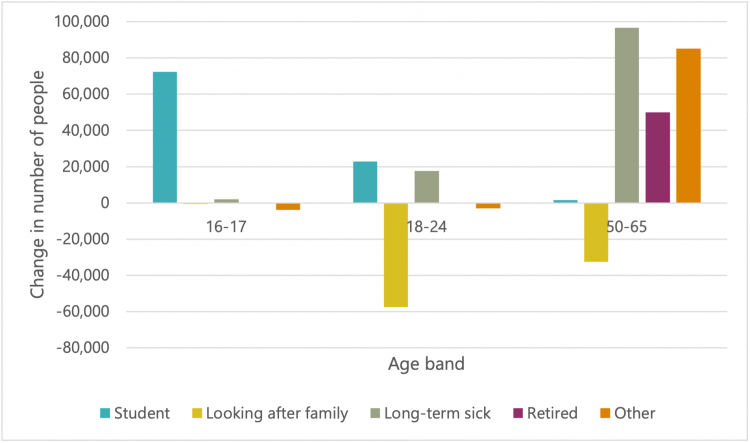

Looking specifically at the oldest and youngest population groups – those responsible for the overall increase in inactivity – the picture becomes even clearer (see figure 3). While growing numbers of young people are delaying joining the labour market to stay in education, a growing number of older workers are either retiring before they reach state pension age or leaving the labour market because of long-term sickness or disability.

Over this two-year period, economic inactivity due to long-term health problems among those aged 50-651 increased by 97,000 or 0.8 percentage points, while the number who had retired from paid work increased by 50,000, or 0.2 percentage points.

The number of people who were economically inactive for a range of other reasons – including those who said they did not want or need a job and those that gave no reason – increased by 85,000. As with other age groups, this was partly offset by a fall in the number economically inactive because of caring responsibilities, which dropped by 33,000.

In total the number of people aged 50-65 who were economically inactive increased by more than 200,000 – or 5 percent - between the third quarter of 2019 and the third quarter of 2021.

- 1This age band includes all people up to the current state pension age.

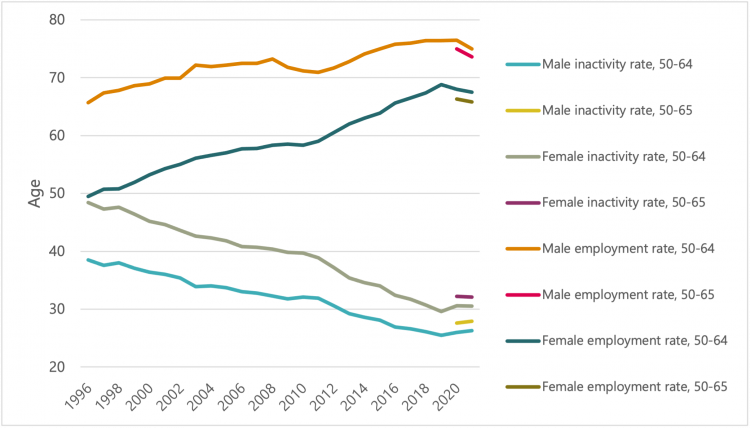

This growth in inactivity has led to a reversal of long-term trends in the labour market that have seen employment rates among older workers increase and inactivity rates fall (see figure 4) since the mid-1990s. Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) figures show between 2019 that 2021 employment rates for men aged 50-64 fell by 2.8 percentage points while inactivity rates increased by 2.4 percentage points. For women over the same period employment decreased by 3 percentage points while inactivity increased by 0.9 percentage points. 2 age, which hit 66 for men and women in October 2020 this shows a significant increase in the number of people leaving the labour market before reaching state pension age. The Institute for Employment studies has calculated that, if pre Covid-19 trends had continued, there would be almost 500,000 more older workers in the labour market today 3

- 2 DWP, Economic labour market status of individuals aged 50 and over, trends over time: September 2021 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/economic-labour-market-status-of-individuals-aged-50-and-over-trends-over-time-september-2021/economic-labour-market-status-of-individuals-aged-50-and-over-trends-over-time-september-2021 Taking into account increases to the state pension

- 3 EIS, Labour Market Statistics, November 2021 https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/resource/labour-market-statistics-november-2021

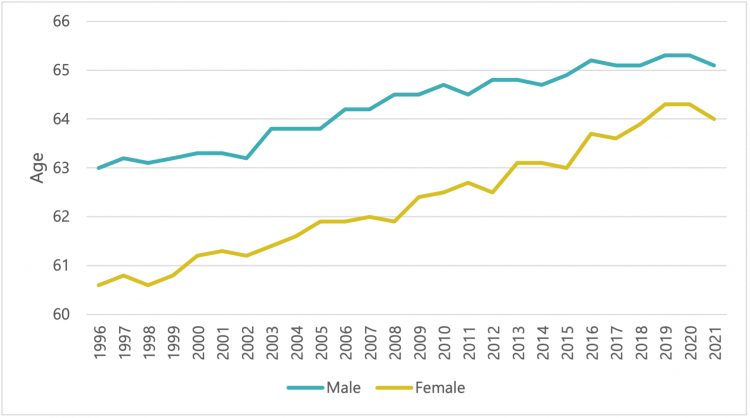

This increase in economic inactivity among older workers is reflected in a fall in the average age of exit from the labour market for both men women, which had also been increasing steadily since the mid-1990s (see figure 5). Between 2019 and 2021 the average age of exit fell by 0.2 years for men and 0.3 years for women.

Extending working lives has been a key aim of government for some time, in recognition of the fact that current generations are living longer than previous generations. The government acknowledges that leaving the labour market before state pension age can be damaging for workers’ health, financial stability and mental well-being, as well as being detrimental to the wider economy.4 This is particularly true for those with no or inadequate levels of occupational pension who are forced to rely on inadequate working age benefits if they are unable to work.

Reasons for leaving the labour market

Older workers are more likely to leave the labour market due to ill-health

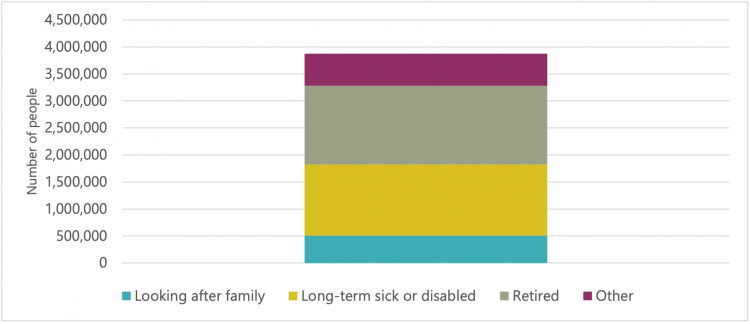

In total, almost 4 million people between 50 and state pension age were economically inactive in the third quarter of 2021. The most common reason for being out of the labour market was retirement (38 percent) closely followed by long-term sickness or disability (34 percent) and caring responsibilities (13 percent).

- 4 ONS, Living longer: impact of working from home on older workers, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/livinglongerimpactofworkingfromhomeonolderworkers/2021-08-25

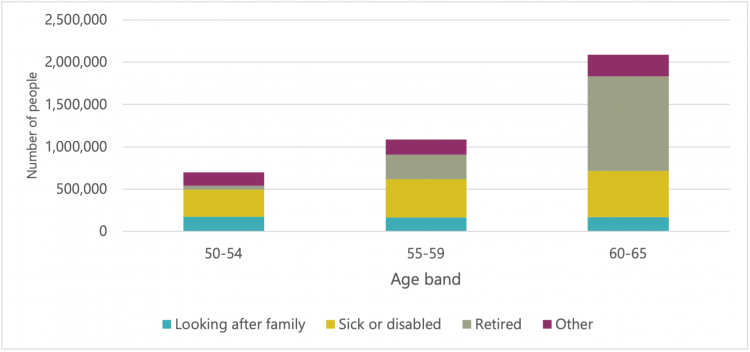

Within this group of older people, levels of economic inactivity increase as they approach state pension age, with just under 2.1 million people aged 60-65 economically inactive (see figure 7). This is primarily the result of increasing numbers of retired people in older age bands. By age 60-65 this accounts for over half the number of people who are economically inactive. Although the levels of inactivity due to long-term sickness increase slightly with age, they are high across all age bands over 50. Among people aged 50-54 almost half of all those who are economically inactive are out of the labour market because of poor health.

Older workers are more likely to leave the labour market due to occupational inequality

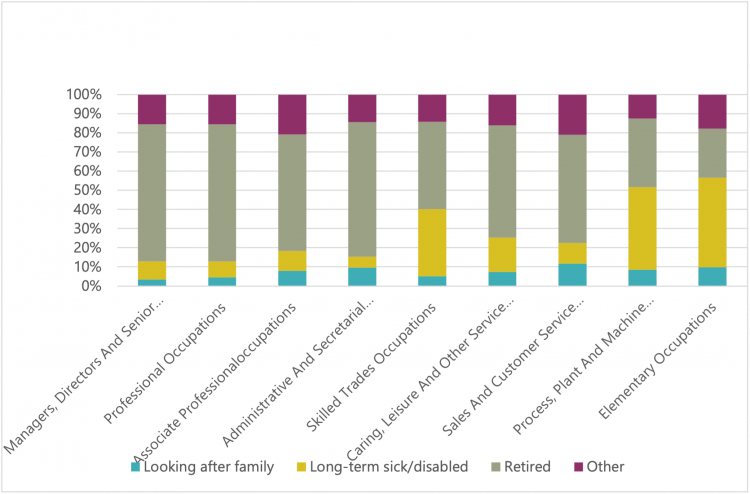

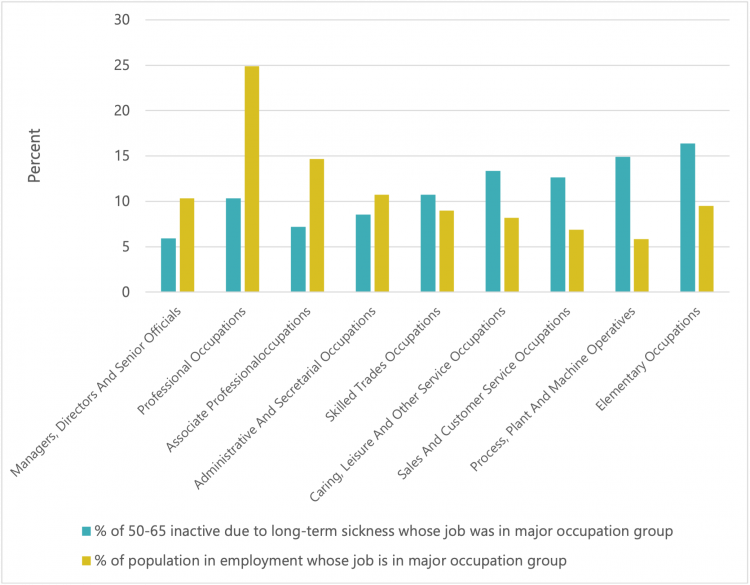

Previous TUC research has highlighted the sharp class inequalities that affect which workers are being forced out of the Labour market early, with those in low paying and manually intensive work the hardest hit.5 This still holds true. Over 60 percent of former managers and former professionals who are economically inactive before they reach state pension age have retired, while around 10 percent have been forced out by ill health (see figure 8). In the lower paid occupational groups of process, plant and machinery operatives and elementary occupations – a category that includes many of the lowest paid jobs such as cleaners, security guards and call centre workers – the proportion who have left the labour market for health reasons rises to around 40 percent. In these two groups more than half of all those who leave the labour market before state pension age do so because of poor health or caring responsibilities.

- 5 TUC, Extending working lives - How to support older workers, https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/extending-working-lives-how-support-older-workers

This high rate of people leaving the labour market early whose last job was in an elementary occupation or as process plant or machinery operatives, means that almost one in three older people (31.3 percent) who are inactive due to health problems came from these sectors (see figure 9). While one in six of the current workforce (15.3 percent) is employed in these parts of the labour market.

People whose last job was in caring, leisure and other service occupations and sales and customer service occupations are also disproportionately likely to be inactive because of health problems. In total, these four low-paid occupation groups account for almost six in ten ill-health early exits (57 percent), despite employing just three in ten workers (30 percent).

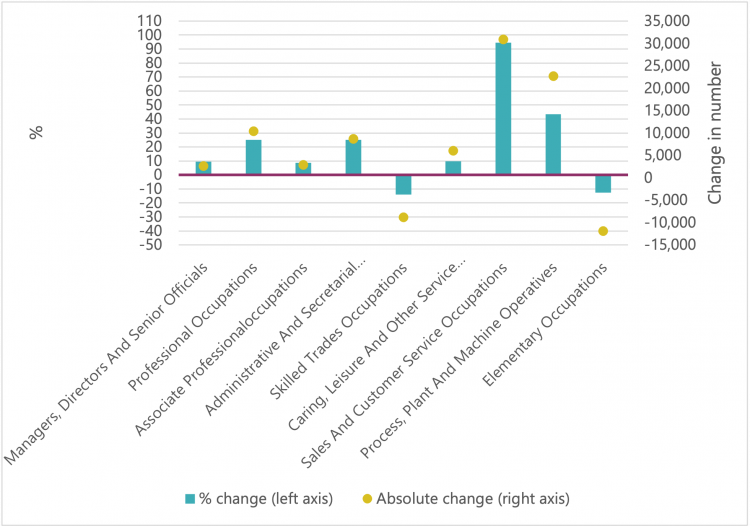

The effect of the Covid-19 pandemic has not been evenly felt across all occupational groups, with sales and customer services and process, plant and machinery operatives seeing sharp increases in the number of people leaving the labour market due to poor health (see figure 10). Between the third quarters of 2019 and 2021 the number of people economically inactive due to poor health whose last jobs had been in these sectors increased by 95 percent and 43 percent respectively.

This is not a uniform story of widening inequalities, however. There has been a fall in the number of workers leaving the labour market due to ill health from elementary professions and skilled trades – two occupation groups with generally high number of ill health early exits – while professional occupations has seen a significant increase.

It does show however, that some sectors of the economy are likely to be hit particularly hard by the economic impact of the pandemic, and older workers in these sectors will be in need of targeted support.

Older workers from Black and minority ethnic groups are more likely to leave the labour market

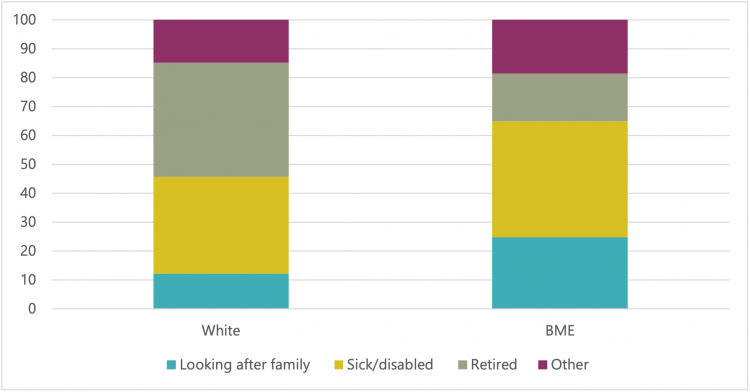

Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers aged 50-65 are less likely to be economically inactive than their white counterparts. Some 26 percent of BME people in this group are inactive compared to 29 percent of white people, with this gap widening by 1 percentage point between Q3 2019 and Q3 2021. But those that are inactive are significantly less likely to be retired, and more likely to be in poor health or have caring responsibilities (see figure 11).

White people in this age group who are economically inactive are more than twice as likely to have retired as their BME counterparts. This is likely to be a result of the significant gap in average pension wealth that means white workers are the most likely to be in a position to choose to retire before they reach state pension age. Average income from private pensions for BME pensioners over 65 is just 71 per cent of the population average.6

Older BME people who are economically inactive are 6.7 percentage points more likely to have left the labour market due to poor health and more than twice as likely to be unable to work because of caring responsibilities.

- 6 Pensions Policy Institute, The Underpensioned Index https://www.pensionspolicyinstitute.org.uk/media/3678/20201208-the-underpensioned-index-exec-summary-final.pdf

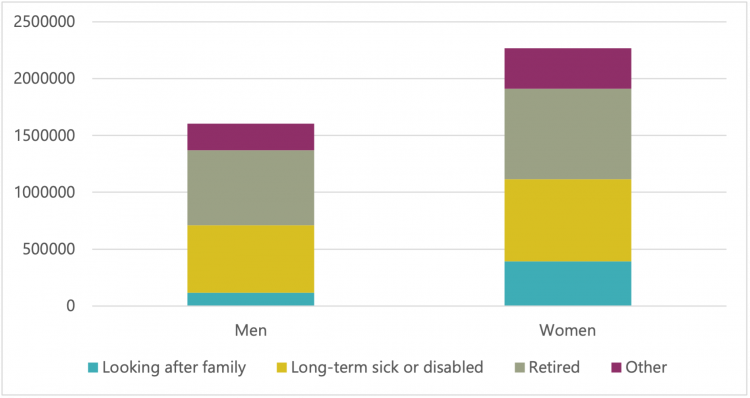

Older women are more likely to leave the labour market than men

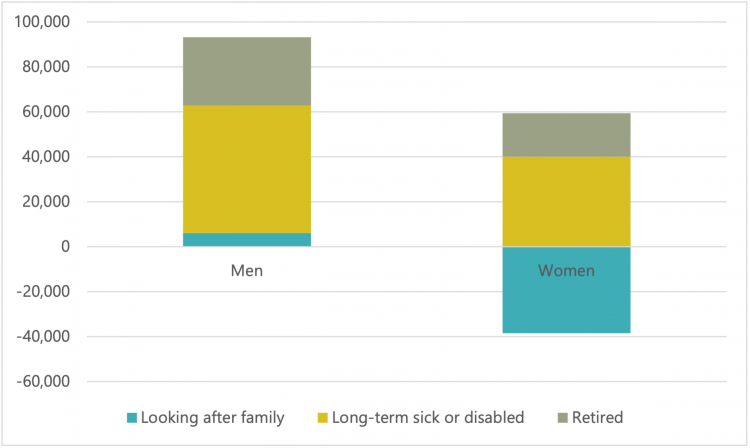

Older women have historically had higher rates of inactivity than older men. Although this gap has closed in recent decades there are still over 660,000 more women aged 50-65 who are economically inactive than there are men (see figure 12). Economically inactive men are more likely to be retired or in ill health than women, but the greatest difference is in the rates of inactivity because of caring responsibilities. The proportion of women in this age group who have left the labour market for this reason (17 percent) is more than twice as high as the proportion of men (7 percent).

While levels of economic activity have fallen for both men and women over the pandemic, the gender activity gap still appears to be closing. This is driven by changes in the number of people out of the labour market because of caring responsibilities. While the number of women aged 50-65 who were economically inactive for this reason fell, there was actually a small increase for men in this age group. There was also a greater increase in the number of older men who are out of the labour market due to ill health and early retirement.

Sustainability of workplace pension incomes

As well as the rise in ill-health early exits, the 50,000 increase in the number of men and women who have left the labour market before their 66th birthday 1 because they have retired from paid work is also a concern. Although many people choose to retire before state pension because they have sufficient resources to maintain their standard of living others simply retire because they cannot find suitable work. There is evidence that the pandemic increased the numbers forced into early retirement in this way. The Financial Conduct Authority found that 23 percent of those who retired between March and October 2020 did so because they had lost their job because of Covid-19. 8 In total, 58 percent of people retiring in this period said they did so because of the pandemic.

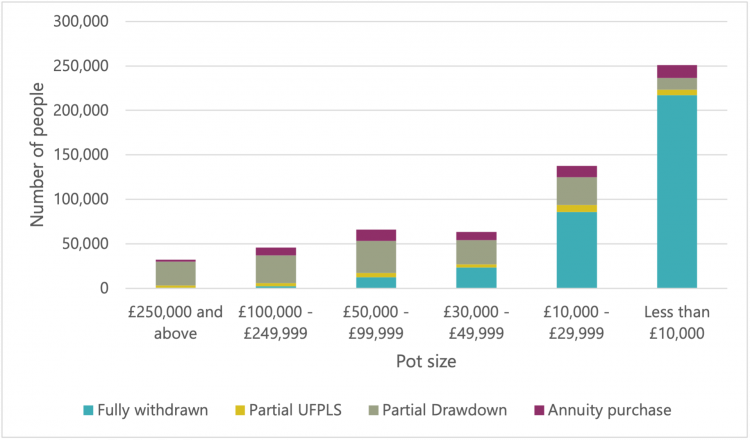

Evidence from the FCA’s retirement income market data also shows that the vast majority of people accessing defined contribution pension pots in 2020/21 had small pots and cashed them out entirely (see figure 14). Two thirds (65 percent) of pots accessed had values below £30,000 while 87 percent of those cashing in pots worth less than £10,000 took the whole amount in cash.

- 1 The state pension age increased from 65 years and 6 months to 66 years in stages between October 2019 and October 2020, so some of those aged 50-65 in Q3 2019 who had retired will have actually reached state pension age, meaning the increase in the number of people retiring before they reach state pension is slightly larger than this 50,000 figure.

- 8 FCA, Financial Lives 2020 survey: the impact of coronavirus, https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/research/financial-lives-survey-2020.pdf

This does not tell us whether the people accessing these pots had other sources of income from pensions, savings, or continued work, and not all of the additional retirees will be relying on a DC pension for retirement income. But it does show that very few people accessing their DC pensions under the ‘pension freedoms’ are using it to provide a sustainable retirement income. It suggests many are using it to supplement incomes or as a bridge before other sources of income, such as a state pension, are accessible.

This combination of an increase in unplanned retirements due to Covid-19 and a large number of people cashing out small pension pots suggests an increased risk that people will exhaust their retirement savings. This would force more older people to rely on working age benefits or pension credit.

Policy recommendations

Safer workplaces

Covid-19 poses a higher risk to older people, so protecting workers from Covid transmission will play a key part in ensuring older people can remain economically active and feel safe in work. There is a legal obligation to assess and manage all risks in a workplace – and to consult with unions and/or the workforce on this process. The 120,000 trained union health and safety reps in workplaces across the UK should be mobilised to help ensure that workplaces are safe, including workplaces with no existing union reps and unions are not recognised.

To control workplace outbreaks the government must ensure that Covid testing remains free, and update guidance on mask wearing and social distancing, as well as rapidly introducing measures to help clean the air in workplaces.

Active and effective enforcement is key to ensuring employers comply with their obligation to provide safe working arrangements, which means funding cuts to the Health and Safety Executive and local authorities will have to be reversed.

And to meet the challenges now facing our labour market, the government should bring unions and businesses together to advise on how to achieve the mission of a high wage, high productivity economy.

Key recommendations:

- Risk assessments: Employers must be compelled to provide airborne protections for workers, with ventilation measures and FFP3-grade face masks. Individual risk assessments must be completed for groups of workers at heightened risk. Publication of workplace-wide risk assessments should be made a legal requirement.

- Regulation and Enforcement: Tougher enforcement is required to incentivise robust risk management, and government must provide a new funding settlement to HSE and local authorities allowing them to invest in inspectorate capacity.

- Covid testing: Government must expand access to rapid testing, keeping it free, with prioritisation for frontline ‘key’ workers.

- ‘Working better’ taskforce: Government must convene a taskforce, chaired by a cabinet minister, bringing together worker representatives, business and independent experts. The taskforce would report on how to achieve the mission of a high wage, high productivity economy before the autumn financial statement.9

Skills

Older workers are the least likely to get ‘off the job training’ from their employers,10 and have for a long time faced additional barriers in the labour market. This discrimination means over-50s who are unemployed are twice as likely as the youngest workers to become long-term unemployed, with just one in three who were made redundant getting back in employment within three months, even pre-Covid-19.11 So many older workers will require additional support if they are to return to or stay in the labour market.

This means enabling workers to access mid-life reviews to help them plan for later life, as well as making sure they are able to access any training they require. There is an important role for Union Learning Representatives in delivering these reviews as workers are likely to be more open with them than their managers about skills gaps and personal pressures.

The Union Learning Fund supported people to access training at work for more than 20 years and played a key role in helping older workers acquire the skills they need to sustain and build their employment prospects. The government should review its puzzling and counter-productive decision to cut the grant for the Union Learning Fund. TUC research has demonstrated that this will reduce the number of adults taking up learning and training, including many older workers.12

Key recommendations:

Mid-life reviews: All workers must have the right to a mid-life career and skills review to help them plan, progress and prosper in later life.

Right to retrain: Government must expand existing skills entitlements and establish a new ‘right to retrain’. These entitlements should be incorporated into lifelong learning accounts and accompanied by new workplace rights, including a new right to paid time off for learning and training for all workers

Funding commitment: Government must invest in skills over the long-term and ensure that this part of the departmental budget is not first in line for cuts. It should also establish a new national social partnership on skills and restore of funding for the successful Union Learning Fund.

Targeted support: In recognition of the additional barriers faced by unemployed or economically inactive older people in returning to the labour market, the government must provide funded retraining schemes targeted at older people.

Health and flexible working

The growing number of older people unable to work because of long-term sickness or disability means that tackling the barriers faced by disabled people in the workplace is also vital for increasing labour market participation. This requires ensuring that older workers who are disabled have access to the support they are legally entitled too and do not face discrimination. It also means giving stronger rights to flexible and home working, which would benefit those managing long-term health conditions or needing to reduce their workload.

Key recommendations:

- Reasonable adjustments: Employers must take all steps they can to ensure they comply with their proactive duty to implement reasonable adjustments for disabled workers, including working from home and flexible work patterns as soon as is possible.

- Pay gap reporting: In order to promote transparency and ensure workforce monitoring is used consistently across employers the government must introduce mandatory disability pay gap reporting.

- Job adverts: Introduce a legal duty on employers to consider which flexible working arrangements are available in a role and publish these in job advertisements, with the new postholder having a day-one right to take up the flexible working arrangements that have been advertised.

- Right to work flexibly: A day-one right to request flexible working for all workers, with the criteria for rejection mirroring the objective justification set out above. Workers should have a right to appeal and no restrictions on the number of flexible working requests made.

Pensions and benefits

To ensure those people who are unable to stay in work into their mid-sixties and beyond are not condemned to poverty, reform of both pension and working age benefits is needed. Reforming universal credit so that it provides an income recipients can live on and doesn’t punish older workers with modest levels of savings would ensure a decent safety net for those forced out of the labour market.

Extending auto-enrolment to ensure more people built up meaningful pension pots would give people greater financial security as they plan for retirement or manage their workload. And developing default retirement income pathways would help people accessing DC pensions they have been auto-enrolled into to do so in a way provides a suitable retirement income.

In the absence of an overhaul of universal credit the government needs to provide targeted support through the benefits system to those approaching state pension age who are unable to work or struggling on low incomes.

And the government cannot push ahead with plans to increase the state pension age. Analysis of ONS population projections has found that the government would have to delay the planned increase from 66 to 67 by 23 years if it is to stick to the formula of people spending up to a third of their working life in retirement.13 The inequalities explored in this report – and the growing gap in life expectancy in the most and least deprived areas14 - show that the independent review of the state pension age taking place this year should focus on the impact of any changes on the least well off.

Key recommendations

- Universal Credit: UC should be increased to 80 per cent of the real Living Wage, and the savings rule that reduces payments to anyone with £6,000 in savings and means those with £16,000 are not eligible must be reformed.

- State pension access: Those approaching state pension age who are unlikely to be able to work again due to caring responsibilities, ill-health, or long-term unemployment should be eligible for early access to their state pension.

- Pension credit: The eligibility age pension credit should be set at a lower level than the state pension age to help all older people struggling to manage on a low income.

- State pension age: Government should shelve plans for further state pension age increases and use the independent review of state pension age to develop a framework that links any future increases to improved life expectancy in the most deprived areas to address the impact of growing longevity inequality.

- Auto-enrolment: Government must phase out the auto-enrolment lower earnings limit and earnings trigger that means employers do not have to auto-enrol low paid workers into a workplace pension or make meaningful contributions to their retirement savings. To ensure workers who have been auto-enrolled into schemes have the best chance of turning their pot into a sustainable income, regulators must develop default retirement income pathways that are suitable for most members, with strong governance and capped investment charges.

- 9 For more details see TUC report, A better normal: Delivering better work now, https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/better-normal

- 10 Centre for Ageing Better, State of ageing in 2020, https://www.ageing-better.org.uk/work-state-ageing2020

- 11 Ibid

- 12 TUC 2020, Getting every adult to level 3- https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/getting-every-adult-le…

- 13 LCP, Twenty million adults could be in line for ‘state pension age reprieve’ as life expectancy improvements ‘collapse’ even before the Pandemic, https://www.lcp.uk.com/media-centre/2021/12/twenty-million-adults-could-be-in-line-for-state-pension-age-reprieve-as-life-expectancy-improvements-collapse-even-before-the-pandemic

- 14 The Kings Fund, How much longer and further are health inequalities set to rise? https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2021/10/rising-health-inequalities-office-health-improvement-disparities

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox