Jobs and recovery monitor - disabled workers

We knew before the pandemic that disabled workers face both a disability pay gap and a disability employment gap1

The disability pay gap is the difference between the median hourly pay of disabled and non-disabled people, and the disability employment gap is the difference between the employment rates of disabled and non-disabled people.

This means that disabled workers are less likely to have a paid job and when they do, they earn substantially less than their non-disabled peers.

This note builds on our previous research into these gaps.

It finds that the disability employment gap has not narrowed, remaining at 28.7 percentage points. And while the disability pay gap has narrowed, it is still much too high. Disabled workers, on average, earn £1.90 per hour less than non-disabled workers.2

Disabled workers are also almost twice as likely to be unemployed than non-disabled workers (8 per cent compared to 4.3 per cent), and more likely than non-disabled workers to be employed on a zero-hours contract.3

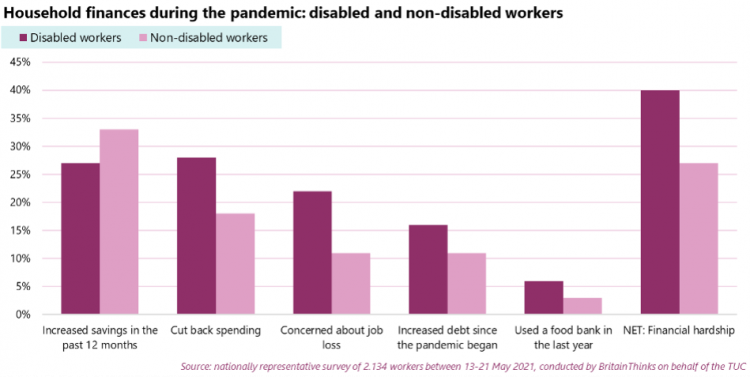

We also look at new findings from a BritainThinks survey, conducted on behalf of the TUC, on household finances and job security. The survey found that during the pandemic, disabled workers have been more likely than non-disabled workers to have cut back on spending and faced an increase in debt. Disabled workers have also been twice as likely as non-disabled workers to use a food bank, and are more likely to be concerned about job losses.

- 1 The TUC has been monitoring disability pay and employment gaps since 2018. Our 2020 analysis can be found here, and includes links to our previous research from 2018 and 2019: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/disability-pay-and-emp…

- 2 Note the word of caution below in the section on the disability employment gap.

- 3 Note the word of caution below in the section on the disability pay gap.

Methodology

Our labour market analysis is based on the Labour Force Survey Q3 2020 to Q2 2021 (referred to as 2020/21). This period has been chosen as it makes use of the most recent data, and allows for comparison with our previous analyses. When relevant, we refer to quarterly data, but this data is not seasonally adjusted so comparisons can only be made between the same quarter in previous years.

Our survey data is taken from a nationally representative survey of 2,134 workers conducted by BritainThinks, on behalf of the TUC, between 13-21 May 2021.

Employment

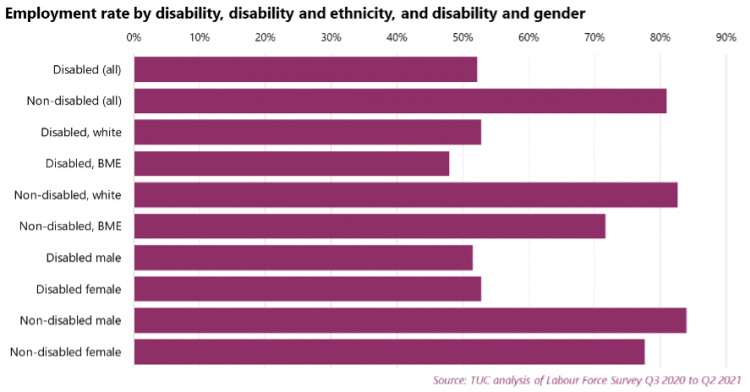

Disabled people experience significant barriers to getting and keeping jobs. This has resulted in a disability employment gap of 28.7 percentage points in 2020/21. The gap has not changed significantly since last year, when it was 28.6 percentage points.

The employment rate for disabled people has fallen across this period, from 53.3 per cent to 52.2 per cent. But the employment rate for non-disabled people has also fallen, from 81.9 per cent to 80.9 per cent.

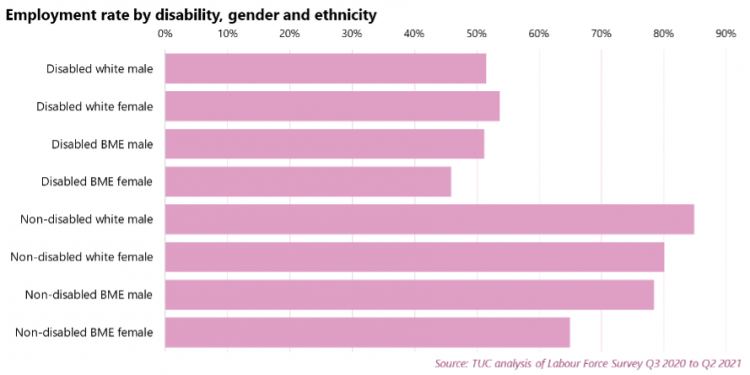

Employment rates among disabled Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) people are particularly low at 48 per cent. The rate for disabled BME women is even lower, at 46 per cent. This compares to 85 per cent among white non-disabled men.

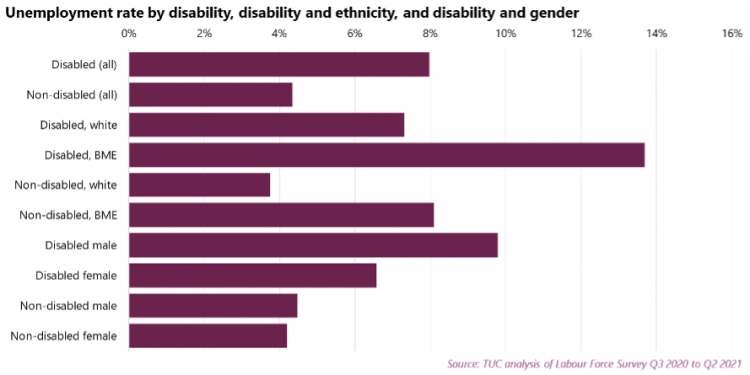

Disabled workers are also more likely to be unemployed than non-disabled workers. The unemployment rate for disabled workers in 2020/21 was 8.0 per cent, almost double that of non-disabled workers (4.3 per cent).

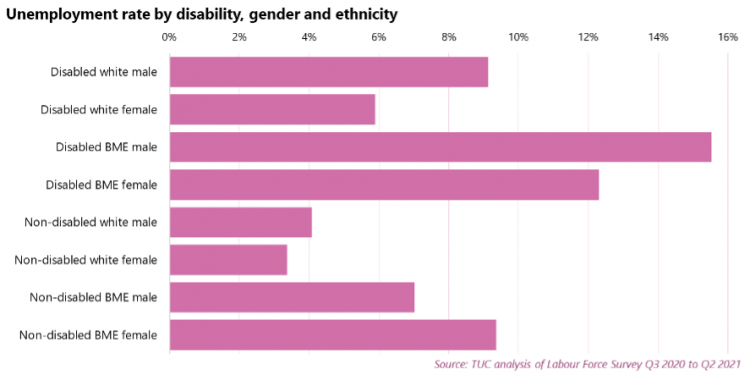

And again, this intersects with other labour market inequalities. Disabled BME workers face an unemployment rate of 13.7 per cent, compared to 3.7 per cent for white non-disabled workers. The unemployment rate is highest among disabled BME men (15.5 per cent).

Disabled workers also face a higher likelihood of being employed on a zero-hours contract (ZHC). 3.7 per cent of disabled workers are employed on a ZHC, compared to 2.7 per cent of non-disabled workers.4

Caution

There is a growing body of evidence that suggests all the narrowing in the disability employment gap from 2010 is accounted for by the expansion in disability prevalence and not by any reduction in underlying disability employment disadvantage.5

If this is true, all work to reduce the disability employment gap and its effectiveness it will need to be re-examined.

Pay

In 2020/21, median hourly pay for disabled employees was £1.90 lower than it was for non-disabled employees. This means that non-disabled employees earn 16.5 per cent more than disabled colleagues.

The gap has narrowed since last year, when it was 20 per cent. But it remains higher than it was in 2017/18 and 2018/19, when the gap was 15.2 per cent and 15.5 per cent respectively.6

Regardless, the pay gap remains much too high. And the pay gap is much for disabled women. Median hourly pay for disabled women is £11.10, compared to £14.60 for non-disabled men. This is a pay gap of £3.50 per hour.

- 4 This is based on TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey Q2 2021.

- 5 Measuring disability and interpreting trends in disability related disadvantage https://www.disabilityatwork.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Briefing-…

- 6 Disability employment and pay gaps 2019, TUC (2019). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/disability-employment-…

Caution

We are cautious about drawing conclusions from the narrowing of the gap due to issues with pay data during the pandemic (which overlaps with both the 2019/20 and 2020/21 analyses). The Office of National Statistics (ONS) has warned that base and compositional effects currently affecting the pay data mean that it should be treated with caution.7

Household finances

Disabled workers have been more likely than non-disabled workers to have seen a hit to household finances during the pandemic. New survey findings show that disabled workers are significantly more likely to have experienced financial hardship during the pandemic compared to non-disabled workers (40 per cent compared to 27 per cent).

Compared to non-disabled workers, disabled workers are also:

- Twice as likely to have used a food bank in the last year (6 per cent compared to 3 per cent)

- More likely to have had to cut back spending at the end of the week or month more since the pandemic began because they have run out, or might run out, of money (28 per cent compared to 18 per cent)

- Less likely to have increased savings in the past 12 months (27 per cent compared to 33 per cent)

- Twice as likely to be concerned about losing their job in the next 12 months (22 per cent compared to 11 per cent)

- More likely to say that levels of debt have increased since the pandemic began (16 per cent compared to 11 per cent)

- 7 Far from average: How COVID-19 has impacted the Average Weekly Earnings data, ONS (2021). Available at: https://blog.ons.gov.uk/2021/07/15/far-from-average-how-covid-19-has-im…

Recommendations

This year the TUC is highlighting our calls on the government to deliver:

- Mandatory disability pay gap reporting for all employers with more than 50 employees. This should be accompanied by a duty on employers to produce targeted action plans identifying the steps they will take to address any gaps identified.

- Enforcement of reasonable adjustments: The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) should get specific ringfenced funding to effectively enforce disabled workers’ right to reasonable adjustments.

- A stronger legal framework for adjustments: The EHRC must update their statutory code of practice to include more examples of reasonable adjustments, to help disabled workers get the adjustments they need quickly and effectively. This will help lawyers, advisers, union reps and human resources departments apply the law and understand its technical detail.

However the TUC has made additional recommendations on how to address the disability employment and pay gaps, which can be found in our 2019 report on this topic.8

- 8 Disability employment and pay gaps 2019 - https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-11/Disability%20doc%20%…

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox