Dying on the job - Racism and risk at work

In June the TUC launched a call for evidence for BME workers to share their experiences of work during Covid-19. More than 1,200 got in touch with the union body.

Of those who contacted the TUC:

- One in five BME workers said they received unfair treatment because of their ethnicity

- Around one in six BME workers felt they had been put more at risk of exposure to coronavirus because of their ethnic background. Many reported being forced to do frontline work that white colleagues had refused to do

- Other respondents said they were denied access to proper personal protective equipment (PPE), refused risk assessments and were singled out to do high-risk work.

Racism at work

Just before the pandemic, a separate ICM poll of BME workers revealed that nearly half (45%) were given harder or less popular work tasks than their white colleagues.

And the poll found that racism was rife in the workplace:

- Just over three in ten (31%) BME workers told the TUC that they had had been bullied or harassed at work.

- A similar percentage (32%) had witnessed racist verbal or physical abuse in the workplace or at a work organised social event.

- Over a third (35%) reported being unfairly turned down for a job Around a quarter (24%) had been singled out for redundancy.

- One in seven (15%) of those that had been harassed said they left their job because of the racist treatment they received.

Previous TUC analysis has found that BME people tend to be paid less than white workers with the same qualifications. And that they are more likely to work in low-paid, undervalued jobs on insecure contracts.

Government must act on institutional and systemic racism

The TUC is calling on the government to:

- Publish an action plan to tackle the inequalities that BME people face, including in work, health, education and justice

- Introduce mandatory ethnicity pay gap reporting and make employers publish action plans to ensure fair treatment for BME workers in the workplace

- Ban zero-hours contracts, and strengthen the rights of insecure workers

- Publish all the equality impact assessments related to its response to Covid-19 and be fully transparent about how it considers BME communities in its policy decisions

Download full report (PDF)

The impact of coronavirus on BME people has shone a spotlight on multiple areas of systemic disadvantage and discrimination. There have been numerous reports produced over the years – some commissioned by the government itself – that have recommended action to tackle discrimination and entrenched disadvantage.

If these recommendations had been acted on, BME workers would perhaps not have suffered the disproportionate number of deaths that have occurred during this crisis.

Current inaction cannot be allowed to continue when the Covid-19 crisis has shown us clearly that this inequality not only limits Black people’s life opportunities but also contributes to prematurely ending their lives.

BME workers experience systemic inequalities across the labour market that mean they are overrepresented in lower paid, insecure jobs. These inequalities are compounded by the discrimination BME people face within workplaces. Our research carried out just before the outbreak of Covid-19 revealed that BME people’s experiences at work are blighted by discrimination: almost half of BME workers (45 per cent) have been given harder or more difficult tasks to do, over one third (36 per cent) had heard racist comments or jokes at work, around a quarter (24%) had been singled out for redundancy and one in seven (15%) of those that had been harassed said they left their job because of the racist treatment they received.

Yet very few had felt able to raise these issues.

As the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on BME workers became clear, a range of individuals and organisations debated why this was the case, with a variety of explanations being put forward. Nowhere in these debates were the voices of BME workers heard. We set out to rectify this, launching a call for evidence to properly understand the issues workers were facing and what their preferred solutions were. What people told us was shocking but not surprising as it directly reflected our research conducted before the pandemic and the experience of BME workers over the years.

One in five of those who responded to our call for evidence said they had been treated unfairly because of their ethnicity at work during the pandemic and around one in six said they had been put at more risk at work because of their ethnicity. BME workers told us about being singled out for higher risk work, denied access to PPE and appropriate risk assessments, unfairly selected for redundancy and furlough and hostility from managers if they raised concerns. Workers repeatedly said that the fact that they were agency workers or did not have permanent contracts was exploited through threats to cancel work or reduce hours, both to silence them and force them to work in higher risk situations.

Workers highlighted several areas where they felt that action was needed to change their experiences of discrimination at work. In the short term, and in response to the pandemic, there are urgent steps that employers need to take.

These include conducting appropriate risk assessments for BME workers. These risk assessments should, drawing on the latest public health advice, consider the particular risks for Black and ethnic minority workers, who have suffered disproportionate harm from the impact of Covid-19. Any assessments should be informed by thorough, sensitive and comprehensive conversations with BME staff that identify all relevant factors that may influence the level of risk they are exposed to, including any underlying health conditions and work arrangements. All workers must have access to appropriate PPE.

BME workers must be able to raise issues without fear of victimisation, and with the belief that things will change for the better. This must involve better reporting and accountability mechanisms, and a willingness for senior staff to actually listen and properly respond to the concerns of BME staff. To support this, more equal BME representation is needed both at a senior and line-manager level.

Employers need to have a clear vision of what a workplace free from racism looks like and be transparent about the levels of diversity within their organisations.

Ethnic monitoring and regular reporting are essential if businesses and other employers are to identify and address patterns of inequality in the workplace. Organisations need to collect baseline data, update this information regularly so that the information can be seen in the context of wider trends, and measure results against clear, timebound objectives.

Employers do not need to wait for the government to introduce mandatory ethnicity pay- gap reporting and action plans.

We recognise that many employers, especially in the private sector, do not currently have detailed systems for ethnic monitoring. However, we urge these employers to act swiftly to introduce workforce ethnic monitoring that allows them to develop an evidence-based plan addressing inequality experienced by BME staff. Without up-to-date ethnic monitoring data on areas such as retention, recruitment and promotion, training and development opportunities and performance management, employers will find it difficult to develop a clear picture of their workplace and identify any areas where BME staff are underrepresented or potentially disadvantaged.

But wider systemic issues also need to be resolved and this scale of change cannot be driven by individual employers alone. Clear leadership is needed from government. The coronavirus crisis, with its terrible impact on BME people, must be a turning point in government willingness to address systemic inequalities for BME people, including at work. Anything short of this clearly signals a satisfaction with the status quo; a state of affairs where lives are blighted and prematurely ended by racism.

In May 2020, the Office of National Statistics (ONS) published an analysis of the number of Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers that had died because of Covid-19, revealing the full disproportionate impact of the pandemic on BME groups. Tragically, before official statistics were released, it was only through pictures of those who had died being shared that this truth was brought into the spotlight.

The analysis shows that when taking into account age, Black men and Black women are 4.2 and 4.3 times respective more likely than white men and women to die from coronavirus. Similarly, men in the Bangladeshi and Pakistani ethnic group were 1.8 times more likely to have a coronavirus-related death than white men when age and other socio-demographic characteristics and measures of self-reported health and disability were taken into account; for women, the figure is 1.6 times more likely.

The ONS analysis found that while geographic and socio-economic factors accounted for over half of the difference in risk, these factors do not explain all the difference, suggesting that other causes are still to be identified. The TUC believes that these other causes include the effects of institutional racism and structural inequality that exist in the world of work.

Unfortunately, the government response to date has failed to fully accept the extent to which structural drivers influence disproportionate death rates, instead suggesting that cultural or genetic factors are playing a larger role. Its coronavirus policy response has failed both to take account of the institutional and structural inequality BME people face and to mitigate its impacts. Strategies for dealing with the pandemic have not taken account of the economic position of people in BME communities, the racism that shapes the lived experience of people from BME backgrounds and the role that race inequality plays in the world of work. Racism remains a matter of life and death.

Some key factors which have placed BME workers are greater risk are:

-

Levels of in work poverty are disproportionately higher in BME communities, as racial discrimination traps BME workers in low-waged occupations and into situations where they are expected to do the hardest and most dangerous work.

-

BME workers are disproportionately working in the frontline jobs that are keeping our communities going during this crisis. Whether it is nursing the sick in hospitals, looking after the elderly in care homes, keeping public transport going or producing and distributing food, BME workers have to go out to work in environments with a higher risk of exposure to coronavirus. The growth of casualised forms of work designed to circumvent employment rights has increased the risks these BME workers face.

-

The UK’s limited social security safety net has left disproportionately more BME workers with no choice but to work during the crisis to pay the rent and feed their families. Often there is no safety net at all, leaving BME workers with no choice but to juggle several precarious jobs to survive.

-

The government’s hostile environment policy, which set out to make staying in the UK as difficult as possible for those without leave to remain, has left many BME workers with no recourse to public funds, or at the mercy of unscrupulous employers who know that because of arbitrary changes in immigration rules they are now undocumented. This places them at much higher risk of working in unsafe conditions.

It is these risk factors, not the ethnic origins of BME workers, that have led them to experience disproportionate numbers of coronavirus deaths.

However, despite growing public discussion about the impact of coronavirus on BME workers, the reality of their lived experiences has largely been excluded from the debate.

From the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, unions have told us that BME people (including migrant workers) have been discriminated against in a number of ways - being singled out for more dangerous or difficult work, not getting access to adequate PPE, not being protected despite having underlying health conditions, being targeted when hours or jobs are being cut and being racially abused by colleagues or customers. We wanted to understand more about this and to put the voices and experiences of BME workers at the heart of the debate about the disproportionate impact of Covid-19. It is only through listening to BME workers and acting on their experiences and preferred solutions that we will effectively identify the issues that we need to address and find the best ways forward. That is why in June 2020 the TUC put out a call for evidence. We wanted to give BME workers an opportunity to place their experiences on record. Over 1,200 workers responded and told us their stories. The findings show how discrimination has compounded the impact of the pandemic on BME workers.

Before the pandemic, we had also commissioned ICM to undertake a survey of over 1,200 black and minority ethnic (BME) workers. This report also sets out the results of this survey, which provides further evidence on BME workers’ experience of discrimination at work.

The unemployment rate among BME people is significantly higher than it is among white people (6.3 per cent compared to 3.6 per cent). 1 BME graduates with a first degree are also more than twice as likely to be unemployed as white graduates. 2 <

In part, this is because BME people face discrimination when applying for jobs. A 2019 report by the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College found that, despite having the same skills, qualifications and work experience, job applicants from an ethnic minority backgrounds had to send 60 per cent more applications than white British candidates before they received a positive response. 3

Discrimination continues once BME people are in work. There are around 3.9 million BME working people in the UK who are far more likely to be in precarious jobs than white workers.

- BME workers are more than twice as likely to be on agency contracts than white workers.

- BME workers more likely to be on zero-hours contracts – one in 24 BME workers are on zero-hours contracts, compared to one in 42 white workers.

- One in 13 BME workers are in temporary work, compared to one in 19 white workers.4

Many BME workers experience the double impact of underemployment and low pay.

BME working people are twice as likely to report not having enough hours to make ends meet and pay in temporary and zero-hours jobs is typically a third less an hour than for those on permanent contracts. 5 This places many BME workers and their families under significant financial stress and has constrained the choices that these workers have during the pandemic around whether they can afford not to attend work.

The stress and uncertainty created by the unpredictability of insecure work blights the lives of workers in ordinary times. But the Covid-19 pandemic has added a more deadly aspect to this lack of workplace power. Many of those filling key roles such as caring, in retail, warehouses or in food delivery are on insecure contracts. But they are reliant on their employers providing adequate equipment and working environment to enable them to work safely. Their insecure contracts make it harder for them to assert their rights for a safe workplace and appropriate PPE; to take time off for childcare responsibilities as schools have closed; and to shield if they or someone they live with is vulnerable. Their insecurity has increased their vulnerability, with all the risks to health and life that that brings.

The McGregor-Smith Review 6 into race in the workplace found that structural bias stands in the way of BME workers’ progression at work:

- 1 TUC analysis of the Labour Force Survey (Q1 2020)

- 2 Black, Qualified and Unemployed , TUC (2016). Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/BlackQualifiedandunemployed.pdf

- 3 Are Employers in Britain Discriminating Against Ethnic Minorities? Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College (2019 ). Available at: http://csi.nuff.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Are-employers-in-Britain-discriminating-against-ethnic-minorities_final.pdf

- 4 “BME Workers Far more Likely to be Trapped in Insecure Work”, TUC: https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/bme-workers-far-more-likely-be-trapped-insecure-work-tuc-analysis-reveals

- 5 Ibid

- 6 Race in the workplace: The McGregor-Smith Review, GOV.UK – Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/594336/race-in-workplace-mcgregor-smith-review.pdf

In many organisations, the processes in place, from the point of recruitment through to progression to the very top, remain favourable to a select group of individuals.

BME employees are overrepresented in the lowest paid occupations and underrepresented in the highest paid occupations. 7 An ONS study on ethnicity pay gaps showed that, on average, BME employees earn 3.8 per cent less than white employees. 8 This varies by region, rising as high as 21.7 per cent in London. It also masks disparities by ethnicity. Despite these significant ethnicity pay gaps, and the underlying inequality that they reflect, ethnicity pay gap reporting is still not mandatory in the UK. Government consulted around 18 months ago on the introduction of mandatory reporting for employers, 9 with a range of organisations, including the TUC, signalling their strong support for this approach. Despite the consultation’s stated aim of enabling “government and employers to move forward [on ethnicity pay gap reporting] in a consistent and transparent way” government has failed to take any further steps, including not yet publishing a consultation response.

While we still wait for government to ‘move forward’ on mandatory ethnicity pay gap reporting, most companies are not voluntarily monitoring and publishing their ethnicity pay gap. Many are not even in a position to do so. A report by the Equalities and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) found that only 36 per cent of employers have monitoring systems in place that would allow them to collect and analyse data to identify if there are differences in pay between different ethnic groups. 10

During the crisis there has rightly been a recognition of the important role that workers that provide essential services to support our communities have played. BME workers are more likely than white workers to be in this key worker group. Forty per cent of BME workers work in key-worker occupations, compared with 35 per cent of white workers. 11

The ONS has released data showing coronavirus-related mortality rates by occupation 12 . The release listed ten occupations as having high male mortality rates. BME men were significantly overrepresented in eight of these occupations. Security guards and taxi drivers were the two occupations with the highest male coronavirus-related mortality rates. Whereas 12 per cent of all men in employment are BME, 28 per cent of men working as security guards and 43 per cent of male taxi drivers are BME 13 .

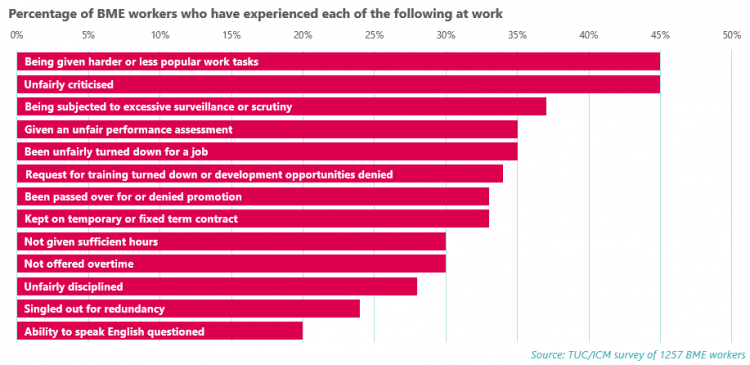

Shortly before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the TUC conducted research with over 1,200 BME workers to understand their experiences of discrimination and disadvantage in the workplace. The findings show significant numbers of BME workers experiencing discriminatory treatment across a range of areas. They paint a clear picture of BME workers being systematically undermined, excluded and forced out of work.

The chart below shows the percentage of BME workers who report experiencing different kinds of discrimination and disadvantage at work including:

- 45 per cent who report being given harder or less popular tasks at work

- 45 per cent who report being unfairly criticised at work

- 35 per cent who report being given an unfair performance assessment

- 35 per cent who report being unfairly turned down for a job

- 24 per cent who report being singled out for redundancy.

- 7 Pay in Working Class Jobs, TUC. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/pay-working-class-jobs?page=3

- 8 Ethnicity Pay Gaps in Great Britain , ONS. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsa…

- 9 Ethnicity Pay Reporting Consultation GOV.UK – Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/ethnicity-pay-reporting

- 10 Measuring and Reporting on Disability and Ethnicity Pay Gaps, Lorna Adams, Aoife Ni Luanaigh, Dominic Thomson and Helen Rossiter IFF Research, August 2018. Available at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/measuring-and-reporting-on-ethnicity-and-disability-pay-gaps.pdf

- 11 A £10 Minimum Wage Would Benefit Millions of Key Workers , TUC. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/ps10-minimum-wage-would-benefit-millions-key-workers

- 12 Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by occupation, England and Wales: deaths registered up to and including 20 April 2020, ONS www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/

- 13 TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey Q1 2020

This report brings into focus the reality of BME workers’ lived experience during the coronavirus crisis and the way that racism shapes the negative experiences that endanger their health, safety and wellbeing. We believe that this is a key factor in the disproportionate number of deaths of BME workers during the pandemic. The report also shows how the institutional racism and discriminatory treatment that BME workers experience has intensified during the crisis.

The TUC believes that the most damaging of these factors are that:

- BME workers are overrepresented in the lowest paid occupations and are far more likely to be in precarious jobs than white workers. As a result, many BME workers may have felt that they had little choice but to work during the crisis (even where there was no access to PPE or other protections) because of the insecure nature of their jobs and lack of access to full employment rights.

- The experience of not having complaints of racism taken seriously or feeling that there may be negative consequences of raising complaints about racism has resulted in BME workers feeling that they have little power to affect their working environment. Many of the comments from BME workers in the report demonstrate that whilst they were aware of being disproportionately exposed to dangerous working situations during the coronavirus crisis, they didn’t feel that they could do anything about it.

- Racism in the workplace has led to BME workers being more likely to be assigned the worst tasks and most dangerous jobs in the workplace. A number of BME workers reported that they were deployed into frontline jobs while white colleagues were kept out of danger. Even when it was possible for them to be furloughed during the crisis BME workers complained that their employers insisted that they remain in the workplace. These experiences highlight the reality of BME workers not being valued as people or as workers.

- The inadequate provision of PPE has had a major impact on BME workers and their ability to protect themselves from Covid-19. A recurring theme in responses to our call for evidence was BME workers reporting feeling forced to work in dangerous situations without PPE where white colleagues were not or that the provision of PPE was discriminatory, even when it was available.

- The failure to conduct risk assessments to identify measures that could be put in place to reduce the risk of exposure to the virus was repeatedly highlighted by BME workers. This resulted in BME workers with underlying health conditions being unnecessarily exposed to the virus.

The TUC believes that it is essential for the voices of BME workers to be listened to and that their experience inform the decisions about what action needs to be taken to tackle racism within the workplace. If these experiences are ignored then, as in the past, the policies and practices that are implemented will not result in the transformative change that we need.

In order to identify effective solutions to the issues highlighted in this report, it is crucial we centre the voices of those workers who experience racism at work on a daily basis. We therefore asked all those who responded to our online survey what changes they would like to see made to tackle the discrimination that they faced.

Some of those that responded were understandably pessimistic about the possibility of changing the entrenched inequality in their workplaces. A number of respondents felt that the only route open to them was to leave their current role, as one IT worker noted:

In a case where I am outnumbered, the best thing is to move on, avoid further stigma.

Others highlighted action that needed to be taken immediately, with the issues most frequently raised including access to PPE for all workers, thorough health and safety risk assessments which properly took into account the increased risks to BME people, and greater protection for those raising complaints.

The need for broader action to change things in the longer term was also frequently raised as a preferred solution. Respondents called for strengthened legislation and real commitment from government and employers to tackle entrenched systemic discrimination. The lack of BME staff at senior levels was repeatedly highlighted as evidence of the need for change.

There are ‘discrimination laws’ in place but a complete absence of anything to deal with the systemic and institutional racism that create the conditions that I have referred to above. THAT NEEDS TO CHANGE.

In most companies and organisations still, why are black people not in senior posts? Racism needs to be rooted out from the core.

Current systems of tackling racism were widely seen as ineffective. Respondents called for effective training to be prioritised, particularly for managers.

In developing our recommendations, we have taken into account the views expressed by the BME workers who responded to our call for evidence. Below we set out our recommendations for how structural and institutional racism in UK workplaces should be addressed.

Government should take immediate action to:

- create and publish a cross-departmental action plan, with clear targets and a timetable for delivery, setting out the steps that it will take to tackle the entrenched disadvantage and discrimination faced by BME people; in order to ensure appropriate transparency and scrutiny of delivery against these targets regular updates should be published and reported to parliament

- strengthen the role of the Race Disparity Unit to properly equip it to support delivery of the action plan

- introduce mandatory ethnicity pay-gap reporting alongside a requirement for employers to publish action plans covering recruitment, retention, promotion, pay and grading, access to training, performance management and discipline and grievance procedures relating to BME staff and applicants

- introduce a ban on zero-hours contracts, a decent floor of rights for all workers and the return of protection against unfair dismissal to millions of working people

- demonstrate transparency in how it has complied with its public sector equality duty through publishing all equality impact assessments related to its response to the coronavirus pandemic.

- Allocate EHRC additional, ringfenced resources so that they can effectively use their unique powers as equality regulator to identify and tackle breaches of the Equality Act in relation to the impact of Covid-19 on BME workers.

Employers should:

- undertake proper job-related risk assessments to ensure that BME workers are not disproportionately exposed to coronavirus and take action to reduce the risks, through the provision of PPE and other appropriate measures where exposure cannot be avoided

- establish an ethnic monitoring system that as a minimum covers recruitment, promotion, access to training, performance management and disciplinary and dismissal, and then evaluate and publish this monitoring data alongside an action plan to tackle any areas of disproportionate under or overrepresentation identified.

- undertake a workplace race equality audit to identify institutional racism and structural inequality

- work with trade unions and workforce representatives to establish targets and develop positive action measures to address racial inequalities in the workforce.

As representatives of workers, trade unions also need to take action to ensure that BME workers are able to raise issues of race discrimination in the workplace and to increase BME workers’ confidence that they will be supported in their struggles for fair treatment at work.

Unions need to:

- ensure BME workers are represented at all levels in union structures and on the main decision-making bodies of their organisations

- consult BME workers about their work, to improve their confidence in unions’ abilities to represent them

- ensure BME workers’ cases are speedily assessed, and concerns addressed

- take account of the race equality aspects of collective bargaining

- discuss with BME workers the bargaining issues that are relevant to their workplace experiences and set out how the mainstream negotiating agenda impacts on BME people’s working lives.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox