Younger workers are getting stuck, not getting on

We like to measure pay gaps here at the TUC.

Most people will be familiar with gender pay gap, the disability pay gap and the gap between the cost of childcare and average wages.

But it’s the pay gap between younger and older workers that is the subject of a new report published by the TUC today.

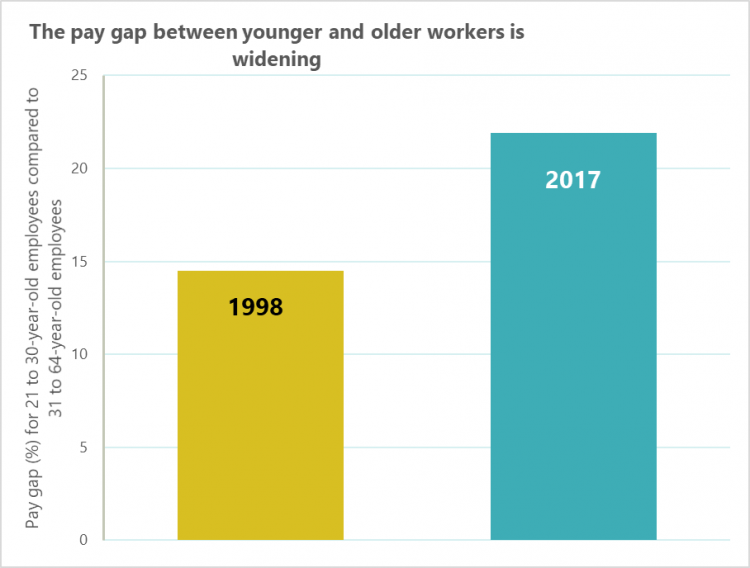

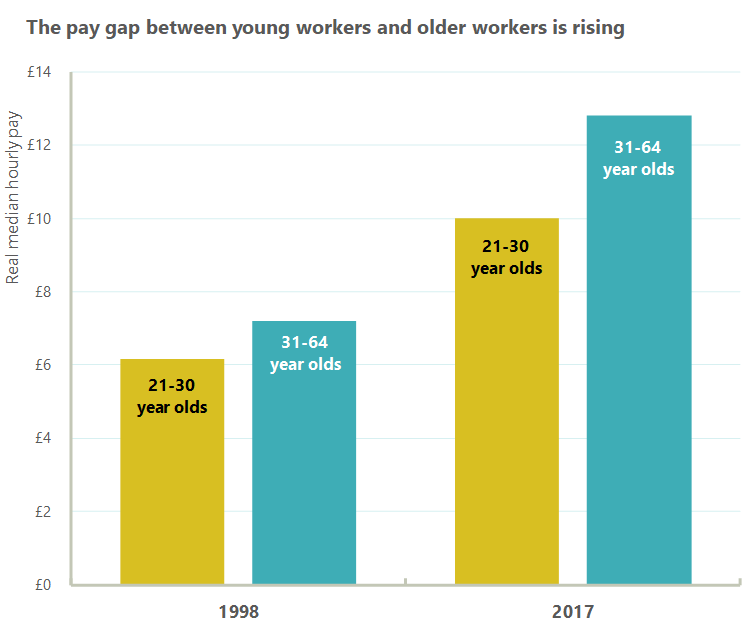

According to our research, the ‘generational pay gap’ – the gap between the average earnings of 21-30 year-olds and 31-64 year-olds working an average 40-hour week - has increased in real terms from £3,140 in 1998 to £5,884 in 2017.

That’s a total increase of £2,744 over the last two decades.

It’s clear that the government and employers must do more to give young people the opportunities they need to get on in work.

But today’s report is also a wake-up call for the trade union movement as the TUC marks its 150th anniversary.

We must do things differently if we are to reach young workers, secure the better pay and conditions they deserve, and build a thriving movement fit for the future.

Stuck at the start

Today’s report shows that the average young worker is only £42 a week better off than young workers were 20 years ago.

By contrast, the average older worker is £95 a week better off – more than double the rate of younger workers.

This generational pay gap isn’t the fault of young workers but is down to several factors beyond their control.

So while the rise in the cost of living has outstripped wages for most people, young workers have been hit by a triple whammy of insecure work, low pay and limited opportunities to progress.

This is partly the result of the continuing wage stagnation and poor growth that has affected many UK workers.

Yet because young workers entered the labour market at a particularly volatile moment after the 2007/08 financial crash, the impacts on their pay are worse.

As a result, their wage gains are smaller than the young workers of twenty years ago.

Poorly paid industries

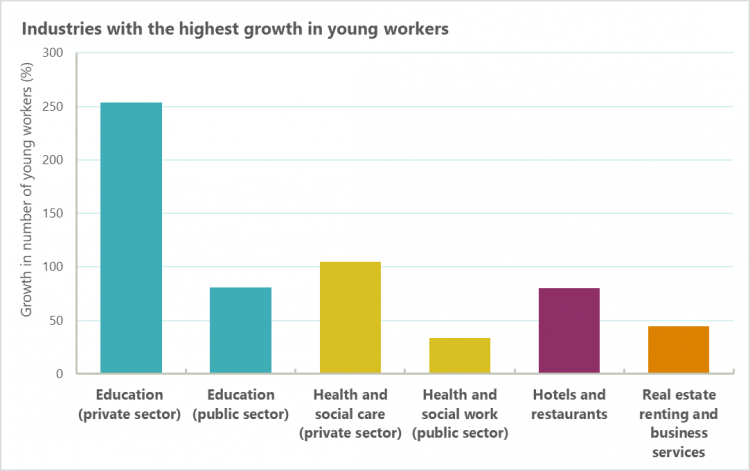

The overrepresentation of today’s young workers in certain industries has also worsened the generational pay gap.

Jobs growth has been generally slower for younger workers than for older workers in the past two decades, but the growth that has taken place has been heavily concentrated in five industries: education; health and social care; hotels and hospitality; real estate, renting and business activities; and wholesale and retail.

Many of these industries are low paid – four out of five have seen the lowest real terms increase of median hourly pay over the past two decades – yet they employ over three-fifths of the 21-30 year-olds who are currently in work.

Meanwhile, last year’s labour market figures show that over one-third of younger workers are in caring, sales or elementary roles compared with just over a quarter of older workers. These jobs are often poorly paid, with zero-hours contracts, agency contracts and temporary work increasingly common.

Barriers to progression

On top of this, there are very few opportunities for young workers to access the skills and training they need in work.

One third of employers admit that they don’t offer any training to their staff – more in some of the industries where young workers are found.

We spoke to nearly 1500 young workers as part of this research, and 17 per cent had not been offered any training in their current job. This rises to 34 per cent for those on part-time contracts, and 37 per cent for workers on zero-hours contracts.

Additionally, less than one-third felt that their current job makes the most of their skills, experiences and qualifications. This drops to a mere 16 per cent for part-time workers.

Being stuck in low paid jobs without opportunities to progress has a significant impact on young workers.

Over the last year alone, 41 per cent were forced to ask their family or friends for financial help due to a shortage of money.

20 per cent had skipped a main meal, nearly one quarter had pawned or sold something, and 22 per cent went without heating in cold weather because they couldn’t afford to pay the bills.

There are long-term impacts too. Over one-fifth put off starting a family, and over a quarter had put off changing careers due to financial worries.

The way forward

We need urgent action from government and employers to help today’s young workers progress in work.

This includes raising the rate of the minimum wage and extending it to 21-24 year olds, strengthening employment rights and increasing employer investment in skills and training.

Creating genuinely flexible, part-time work at all levels of an organisation should also be a priority for employers.

We’ve spoken to countless young workers in low paying sectors over the last 18 months who feel overwhelmingly that nothing will change.

But we know that things can: trade unions have fought for higher pay, better terms and conditions and access to skills and training for more than 150 years.

However, our movement is ageing, with less than 10 per cent of low paid young people trade union members.

So while it’s true that young workers need trade unions more than ever, we need them too.

But if unions are to reach young workers, they need to be innovative and try different approaches to organising in the workplace.

That means going to where young workers already are rather than expecting them to come to us and using language that young people understand.

We must show today’s young workers that things can be better, that other people share their problems at work, and that these problems can be solved when they come together.

After all, stronger unions mean better jobs and a more prosperous economy for everyone - whatever their age.

Download the full report, Stuck at the start - young workers' impressions of pay and progression (PDF)

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox