The failure of austerity – and how to fix it

Austerity was supposed to repair the economy and the public finances.

But a decade after it was inflicted on the country by Tory Chancellor George Osborne, the UK economy is in a dire state.

GDP growth has hit a new low, employment is falling and insecure work has mushroomed. The pay crisis goes on and financial hardship has forced too many into debt.

On top of this the threat of an economically disastrous no-deal Brexit persists, while the IMF is warning of a “precarious” global economic outlook.

Political choices around austerity may finally be changing, but that hasn’t stopped its architects from claiming it was a roaring success.

But they can’t hide the truth forever: austerity is ending not because it did its job, but because it didn’t work.

That’s a fact that politicians would do well to remember during this general election campaign.

Because the evidence shows that austerity strangled the green shoots of economic recovery that were sprouting when the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition took office.

Austerity undermined improving public finances and suppressed tax revenues, with cumulative government borrowing through to 2023-24 now likely to be double (+£450bn) the original plan to get it down to zero in five years.

Our recent report ‘Lessons from a decade of failed austerity’ explains this in detail, demonstrating how austerity policies failed in every economy they were tried.

So it’s the politicians who started austerity that have questions to answer, not those who want to end it today.

And those who weakened the economy through years of cuts should not be questioning spending increases to strengthen it.

That’s why the next government shouldn’t be timid about ending austerity. It’s the right thing to do for working families.

How austerity failed – pay and jobs

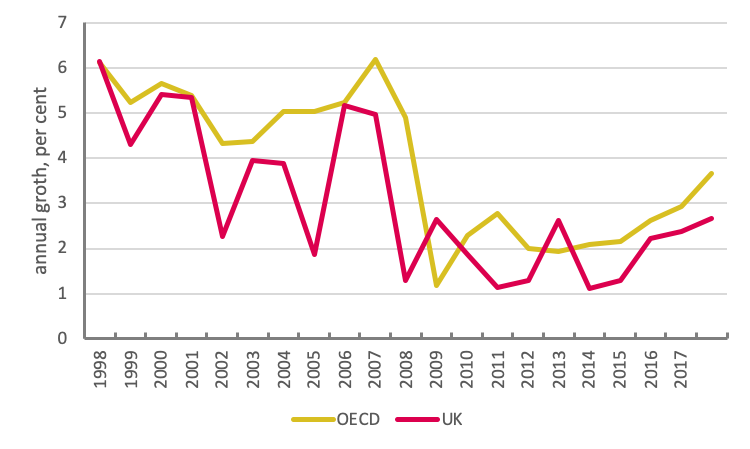

On average, pay growth halved across OECD countries in the nine post-crisis years compared to the nine pre-crisis years.

The chart below shows the OECD average slowing from 5 per cent before the crisis to 2.5 per cent after the crisis, with the UK down from 4 to 2 per cent. For many countries – including the UK – price rises mean that the standard of living has fallen over the last decade.

The architects of austerity like to claim that it heralded a jobs miracle in this country.

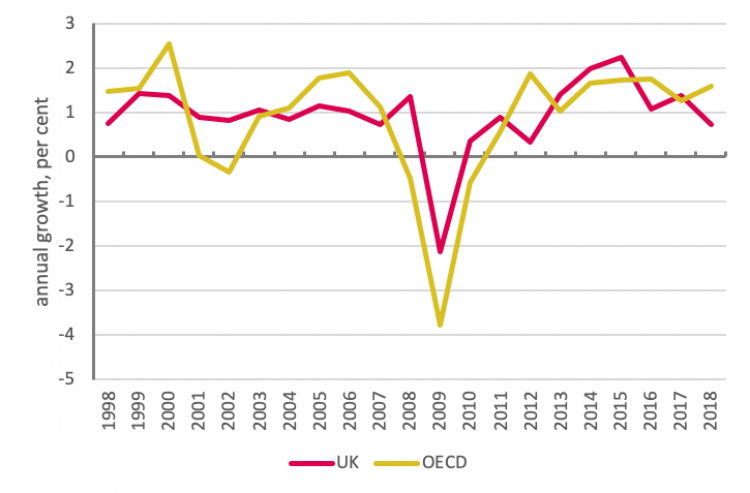

Yet a quick glance at the OECD figures shows that employment growth since the crisis is little different to pre-crisis rates.

What is clear is that the austerity decade coincided with an explosion in the growth in insecure and bad quality work across the OECD.

Renewed calls by business for greater ‘flexibility’ have led to increased attacks on trade unions. The result is rising in-work poverty.

This was the conclusion drawn by the UN rapporteur on poverty, Philip Alston, during his visit to the UK earlier this year.

Alston explicitly rejected the government’s jobs narrative, warning that “even full-time employment is no guarantee against in-work poverty”.

How austerity failed – economic growth

Low wages and insecure work are the symptoms of a weak economy. And this weakness is the direct result of austerity.

There is nothing new about austerity.

In the 1930s it was called ‘economy’, a verbal sleight of hand that the National Executive of the Labour Party branded “the exact reverse of the truth” in 1944.

This time the argument was dressed up as ‘expansionary fiscal contraction’ or EFC.

We were told that ‘fiscal contraction’ – or cutting government spending – would be ‘expansionary’, so that it increased other types of spending.

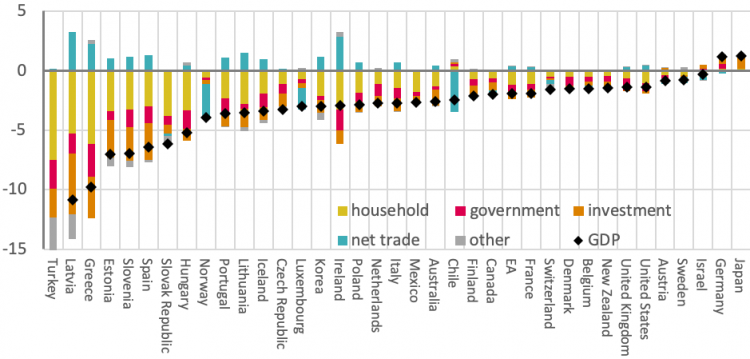

But the record of the past decade proved this theory to be almost entirely wrong, as the following chart demonstrates.

It compares growth before the crisis (1999-2007) and after the crisis (2010-2018) for different sectors of OECD economies. The black diamond represents the change in GDP growth for each country.

The proponents of EFC promised that cuts to government spending (shown here in crimson) would be offset by increased spending across all other categories.

This was categorically not the case. In every country that cut government spending, almost every other category of spending also fell (apart from net trade).

The exceptions were Germany and Japan, which never cut their public budgets in the first place.

The result is that GDP growth after the crisis was worse – much worse in many cases – than before it for every country that pursued austerity economics.

In 2012, the IMF warned that it had greatly underestimated the relationship between government spending and the economy and duly revised its so-called multipliers up to between 0.9 and 1.7.

This change amounted to an admission that spending cuts had damaged economic growth and spending increases would support growth.

Unfortunately, that warning was ignored.

Productivity as a red herring

Politicians and economists who defend austerity like to point to low productivity to explain away poor growth.

But productivity is a result of failed policy, not the cause of failed outcomes.

As we have seen, the labour market has mainly adjusted to low growth through price (i.e. lower wage growth) rather than quantity (i.e. unchanged jobs growth).

So for both the UK and the OECD as a whole, low productivity is the result of comparing low GDP growth with relatively high jobs growth.

This is simple maths, not the convoluted (and failed) economics of the productivity puzzle.

The bottom line is that the best way to avoid low productivity is to avoid cuts. So Germany and Japan are among those who do least badly, while Spain and Ireland in fact do best but at the expense of sharply reduced employment growth.

MPC member Gertjan Vlieghe recently said he “would have some sympathy” with the idea “if only there was more demand stimulus, higher productivity growth might return”.

How austerity failed – growth and the public finances

According to the austerity lie, government spending cuts were necessary to repair the public finances by Gordon Brown’s recession.

It’s now crystal clear that the public finances were not repaired by cutting spending, but by the recovering economy.

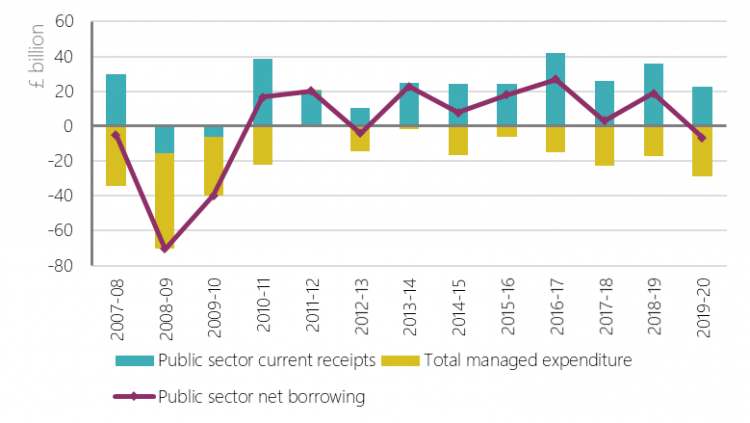

The chart below shows how.

Here we see the deficit (the purple line) blowing up in 2008-09 as government revenues (the blue column) collapsed during the global recession.

The turnaround into 2010-11 did not come because of spending cuts, but because tax revenues recovered.

But by 2012-13, the imposition of austerity policies had stifled the economic recovery and reversed any gains in the public finances.

At this point George Osborne began to ease off the austerity, and the Bank of England threw the monetary kitchen sink at the economy.

This pulled the economy back from the brink, helping to improve revenues and the public finances.

Yet the recovery was always slower than expected, because going easier on austerity was still austerity.

And this meant that the government missed every single target it set to reduce borrowing – which let’s not forget was why they introduced austerity in the first place.

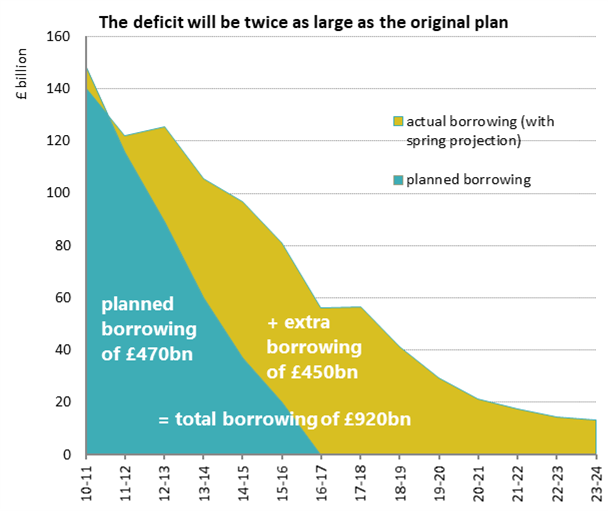

In cumulative terms the government expected to borrow £470 billion over 2010-11 to 2015-16, with borrowing hitting zero in 2016-17 (reinforced with the pathetic and toxic ides of a budget surplus law).

In fact, from 2010-11 to 2023-24 borrowing is likely to be around £920 billion – a colossal £450 billion more than expected.

You can see the difference between what the government promised and what it delivered below.

In 2010, Osborne reckoned debt would fall to 67% of GDP. This spring, debt was shown peaking at 85% and hitting only 73% by 2025.

So not only did austerity not deliver growth, it also failed to repair the public finances.

Conclusion

The lessons from a failed decade of austerity show why it has finally fallen out of favour.

The only remaining question is why it look so long for those in power to wake up.

Thankfully, the Bank of England has recognised in its November Monetary Policy Report that higher government spending is now boosting growth.

Threadneedle Street appear relieved that task of supporting the economy is finally being shared.

But it’s a travesty that such an economically ruinous policy was ever allowed to see the light of day.

The politicians responsible for austerity owe working people an apology.

They promised it would help them get good jobs and better pay. It didn’t.

They promised it would help to grow the economy. It shrunk it.

They promised it would help to repair the public finances, but the national debt is bigger than ever.

And it’s working people who’ve paid the heaviest price for this failure. They’ve had to cope with the longest wage squeeze in centuries, an explosion in insecure work and zero-hours contracts, record levels of in-work poverty, and crumbling public services that we all rely on.

Working people deserve better than this.

Public investment in health, education, housing, welfare, culture, and transport is not just compatible with a working economy and a decent labour market – it’s fundamental to it.

After all, that is exactly what the Attlee government proved to such great effect after the war.

And that’s what the next government needs to do to fix Britain and put working-class families first.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox