Raising pay for everyone

Delivering a high wage economy will take more than wishful thinking. It requires a credible plan to progress the economy towards high-wage, high-skilled and secure jobs. And action to move us away from a reliance on low-paid and insecure work.

In this report the TUC sets out a framework which can get pay rising. Our approach is designed to deliver an end to the longest pay squeeze in modern history and a return to normal wage growth. It is underpinned by a plan to raise the minimum wage to £15 an hour as soon as possible so that no workers are left behind.

A plan for wage growth

Workers are suffering the longest and harshest wage squeeze in modern history. More than a decade on from the financial crisis, UK workers are earning £88 a month less – in real terms – than in 2008. The government needs to put an end to this by delivering a return to normal wage growth of the kind seen before the financial crisis.

The government must deliver:

- A macroeconomic approach which boosts demand and creates growth

- A plan to strengthen and extend collective bargaining across the economy including introducing fair pay agreements to set minimum pay and conditions across whole sectors

- A life-long learning and skills strategy to fill labour shortages, boost productivity and so workers can update their skills throughout their working life

- Corporate governance reform to prioritise long-term sustainable investment and growth, rather than short-term focus on shareholder returns

- Industrial and trade policies to promote good jobs and ensure that businesses compete on a level playing field

- Making decent jobs a requirement of all government spending and procurement.

A plan for a £15 minimum wage

While top pay and profits are soaring, working families at the sharp end desperately need a steady boost to their incomes. Alongside action to deliver decent wage growth across the economy, the government should put the minimum wage on a pathway to £15. The minimum wage is now part of the fabric of our labour market. It is popular and enjoys broad political support. The academic consensus is that it boosts wages without creating unemployment. During the last couple of decades, the evidence has only got stronger in favour of a higher wage floor.

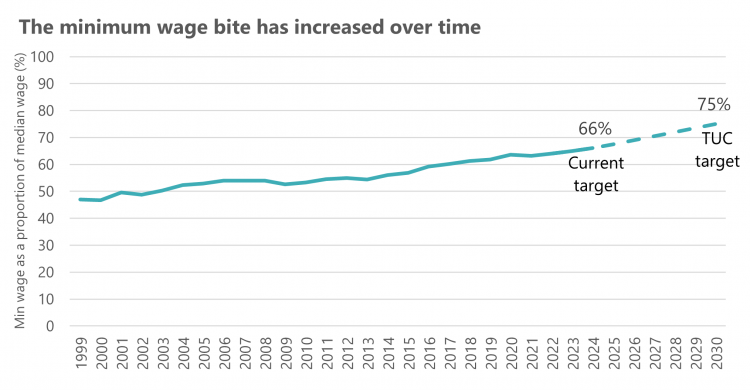

The government needs to achieve two key things to deliver a £15 minimum wage. First, it should set a new minimum wage ‘bite’ target at 75 per cent of median hourly pay. The bite of the minimum wage has increased throughout its history, beginning at 47 per cent and now on its way to 66 per cent by 2024. The evidence continues to show a positive effect on wages and no adverse impacts on employment. The Low Pay Commission should be tasked with progressing the minimum wage to this higher target based on prevailing economic circumstances.

Secondly, the government needs to deliver a return to normal wage growth. Recent progress on the minimum wage has been dampened by stagnant wage growth. But it is only since the financial crisis that wage growth has stalled. From 1970 until 2007 real wages grew by an average of 33 per cent a decade before falling below zero in the 2010s.1

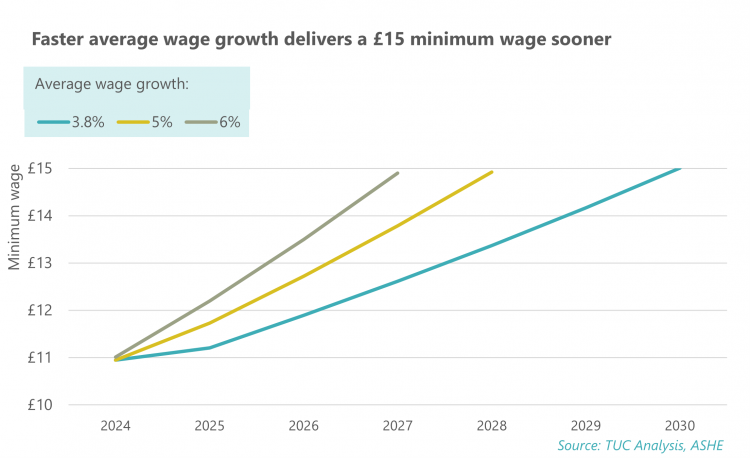

Between 1997 and 2010 nominal wages grew by an average of 3.8 per cent a year. At the very least, we need to see this level of growth again. This is conservative following over a decade of stagnation. Higher levels of sustained pay growth are needed to recover lost ground and to help workers cope with soaring living costs now. But even this level of wage growth would deliver a £20 median wage by the end of the decade. In combination with a 75 per cent bite, it would establish a £15 minimum wage. Higher wage growth should deliver a £15 minimum wage sooner, and the TUC believes we should reach £15 as soon as possible.

Workers covered by collective bargaining will see their wages rise to these levels more quickly. In sectors with good collective bargaining coverage, or where profits are rising, a £15 floor can be implemented earlier. Fair Pay Agreements should be rolled out, and trade union restrictions should be lifted, so workers can win higher pay ahead of the minimum wage.

- 1 Resolution Foundation (July 2022) Stagnation nation: Chapter One https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/reports/stagnation-nation-2/

A plan for wage growth

We are currently in the longest and harshest pay squeeze in modern history

The serving Prime Minister and former Chancellor have pledged to deliver a high wage economy at least 20 times in parliament over the last year. This is sorely needed after their party has overseen the longest pay squeeze since Napoleonic times.2 More than a decade on from the financial crisis, UK workers are earning £88 a month less – in real terms – than in 2008. As the government’s target for the minimum wage is tied to median earnings, this has also put a squeeze on the wage floor. The government needs to put an end to this by delivering a return to normal wage growth of the kind seen before the financial crisis.

Creating an economy based on decent work

We need to change the way our economy works so that economic growth translates into good quality jobs. This requires an institutional environment that encourages the development of business models based on high-wage, high-skilled and secure jobs, rather than a reliance on low-paid and insecure work. Without reforms that hardwire decent work into business models, strategies to boost research and development, or to attract new investment, while welcome, will not deliver the good jobs people need.

To change the economic incentives that shape our economy, we need a new macroeconomic approach, a lifelong learning strategy, reform of corporate governance and industrial policies, and new measures to strengthen workforce voice and collective bargaining to give working people more power in the workplace.

A macroeconomic approach which boosts demand and creates growth

The UK has had some of the worst pay growth internationally, ranking 29th out of 33 OECD nations for wage growth since 2007.3 On top of this workers are now confronting a recession and a rise in unemployment of at least one million.4 While workers are blamed by policymakers for seeking pay rises when real pay is collapsing, those with power have protected their profits and bonuses, and continue to escape blame.5

What we need now is a strategy to deliver decent pay and grow the economy. Forcing workers to take the hit while the wealthy increase their wealth has led us into crisis after crisis. We need a new approach the puts workers ahead of wealth and a productive economy ahead of an extractive economy. That means investing in UK workers, in the secure green energy supply we need, and in boosting jobs in the UK – in the public and private sector. Workers deserve better than another decade of pay loss.

Strengthening workforce voice and collective bargaining

Giving workers stronger rights to organise collectively in unions is key both to raising pay and working conditions and giving workers more say over their working lives. Collective bargaining promotes higher pay, better training, safer and more flexible workplaces and greater equality. The absence of a collective approach to driving up employment standards has led to the poor pay and conditions that are now resulting in labour shortages across the country.

- We need to give workers stronger rights to speak with one voice and bargain with their employer and give unions access to workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership, following the New Zealand model.

- And starting in sectors that are characterised by low pay and poor conditions, we need to create new bodies for workers and employers to come together to set minimum standards and Fair Pay Agreements across the sector, starting with social care.

A new lifelong learning and skills strategy for all workers

The TUC is calling for a new national lifelong learning and skills strategy based on a vision of a high-skill economy, where workers can quickly gain both transferable and specialist skills to build their job prospects. Delivering this would require:

- A significant boost to investment in learning and skills by both the state and employers. People should have access to fully-funded learning and skills entitlements and new workplace training rights throughout their lives, expanding opportunities for upskilling and retraining.

- These entitlements should be incorporated into lifelong learning accounts and accompanied by new workplace rights, including a new right to paid time off for learning and training for all workers.

Corporate governance reform to promote long-term, sustainable growth

Shareholder primacy in corporate governance encourages directors to prioritise shareholder returns over wages and long-term investment, fuelling short-termism and poor employment practices. We need to address shareholder primacy through reform of directors’ duties and promoting workforce voice in corporate governance.

The inclusion of worker directors on company boards would bring people with a very different range of experiences into the boardroom, which would help to challenge ‘groupthink’ and change the culture and priorities of the boardroom, improving the quality of board decision-making.

- Directors’ duties should be reformed so that directors are required to promote the long-term success of the company as their primary aim, taking account of the interests of stakeholders including the workforce, shareholders, local communities and suppliers and the impact of the company’s operations on human rights and on the environment.

- Company law should require that elected worker directors comprise one third of the board at all companies with 250 or more staff.

Industrial and trade policies to promote good jobs

To boost domestic manufacturing, services and technology development, and reap the full benefit of developments in infrastructure and renewable energy, the government should adopt strong trade and procurement policies to strengthen local supply chains and raise employment standards.

- The UK government should use local content requirements where they are legal and needed.

- Trade deals and WTO rules should be used as a lever to lock in the highest standards by enforcing respect for International Labour Organisation (ILO) standards. Too often, rights have been defined disparagingly in trade deals as ‘non-tariff barriers’ that should be removed.

Government leading by example – public services, job creation and procurement

The government should lead by example by showcasing good quality employment practices as an employer and making decent jobs a requirement of all government spending so that the power of government spending is used to drive up employment standards.

- The government and public sector employers should end the pay squeeze for public sector workers and make up for lost earnings over the last decade.

- The government should build job creation and job quality tests into public investment decision-making and procurement standards and use Olympics style agreements to guarantee decent jobs in big infrastructure projects.

- The TUC has called for an £85 billion green infrastructure investment package to ensure delivery of our net zero commitments and create 1.24 million quality jobs.

A plan for a £15 minimum wage

The TUC believes we need a plan to take the wage floor beyond the government’s current target to a £15 minimum wage as soon as possible. This is achievable with a more ambitious minimum wage target and a return to normal levels of wage growth. The government should set out a minimum wage target of 75 per cent of median hourly pay. It should also set out a plan to deliver a return to normal pre-crisis wage growth. Between 1997 and 2010 wages grew by an average of 3.8 per cent a year. At the very least, we need to see this level of growth again. The Low Pay Commission should chart the exact path of the minimum wage aiming for these targets.

Consensus and evidence

The economic consensus has shifted strongly in favour of the minimum wage. Before the minimum wage was introduced, the Conservative Party, business groups and many academics argued that it would create unemployment.6 Even as late as in 1995 the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) was arguing that “even a low minimum wage would reduce job opportunities”.7 The conventional wisdom was that a higher price for wages would cause fewer jobs to exist. This has been comprehensively disproven. The minimum wage has been in place alongside record levels of employment.

The UK government recently commissioned a review of the most up-to-date international evidence8 on minimum wages. This shows that minimum wages are effective at raising wages and have very limited adverse impacts on levels of employment. Academics who have long argued this are now being rewarded. The 2021 Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to Card, Angrist and Imbens for applied research they did in the 1990s that showed minimum wages did not lead to job losses.9

In 2015 the government announced the National Living Wage (NLW) policy. This has led to faster increases in the wage floor over the last seven years. It has contributed further evidence that shows the minimum wage is effective and can be pushed further. The Low Pay Commission recently reviewed the first stage of the NLW rollout. It concluded “our assessment of the first stage of the NLW’s journey is positive. It increased hourly and weekly pay for the lowest-paid workers at an ambitious pace. It did so with minimal effect on employment and hours.”10

The Institute for Fiscal Studies also comes to similar conclusions. In its review11 of the NLW it finds that minimum wage increases have had “substantial effects on wages” and that signs of adverse impact on employment were “small, and not statistically significantly different from zero.”

There may be levels of minimum wage which would cause job losses, but we have clearly not reached them yet. The Low Pay Commission model provides a safe mechanism for establishing the evidence around how high we can push the minimum wage. The Low Pay Commission should continue to make annual recommendations for the minimum wage, gradually taking it to a new higher target, and assessing the impact on the labour market as they go.

Set the ‘bite’ target at 75 per cent

Since the minimum wage was introduced, it has increased as a proportion of the median wage (known as the ’bite’ of the minimum wage). It started at 47 per cent in 1999 and is heading to 66 per cent by 2024, reflecting in part the failure to get wages rising across the board.

- 2 Politics.co.uk (20 Jun 2022) UK workers have lost nearly £20,000 in real earnings since 2008 https://www.politics.co.uk/opinion-former/press-release/2022/06/20/uk-workers-have-lost-nearly-20000-in-real-earnings-since-2008/

- 3 TUC (21 Mar 2022) UK workers miss out on £4,000 in pay growth compared to OECD average since 2007 https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/uk-workers-miss-out-ps4000-pay-growth-compared-oecd-average-2007-tuc-analysis

- 4 Bank of England (August 2022) Monetary Policy Report https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2022/august-2022

- 5 TUC (August 2022) Jobs and pay monitor - Why we need a pay rise https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-pay-monitor-why-we-need-pay-rise

- 6 House of Commons Library (January 1995) A Minimum Wage https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/RP95-7/RP95-7.pdf

- 7 House of Commons Library (December 1997) National Minimum Wage Bill https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/RP97-133/RP97-133.pdf

- 8 Arindrajit Dube (2019) Impacts of minimum wages: review of the international evidence https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/impacts-of-minimum-wages-review-of-the-international-evidence

- 9 Nobel Prize (2021) The Prize in Economic Sciences 2021 https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2021/summary/

- 10 Low Pay Commission (2022) The National Living Wage Review 2015-2020 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1076517/NLW_review.pdf

- 11 Institute for Fiscal Studies (December 2021) The impact of the National Living Wage on wages, employment and household incomes https://ifs.org.uk/publications/15876

In 2016 the government introduced the National Living Wage (NLW) policy. This introduced medium-term targets for the minimum wage for the first time. In pursuit of these targets, the government shifted from extreme caution about minimising job losses to tolerating some increased risk. The first target was a minimum wage set at 60 per cent of median hourly pay by 2020. Once this was achieved, the current target was set at 66 per cent of median pay by 2024.

These targets have proven to be successful. The minimum wage has increased faster than before without negative impacts on employment levels.12 It is looking almost certain that the 66 per cent target will be achieved. A further target of 75 per cent should be set. This should operate in the same way as the current target, with the Low Pay Commission responsible for recommending the exact path. The above chart shows the path so far and a proposed increase to 75 per cent.

Return to normal wage growth

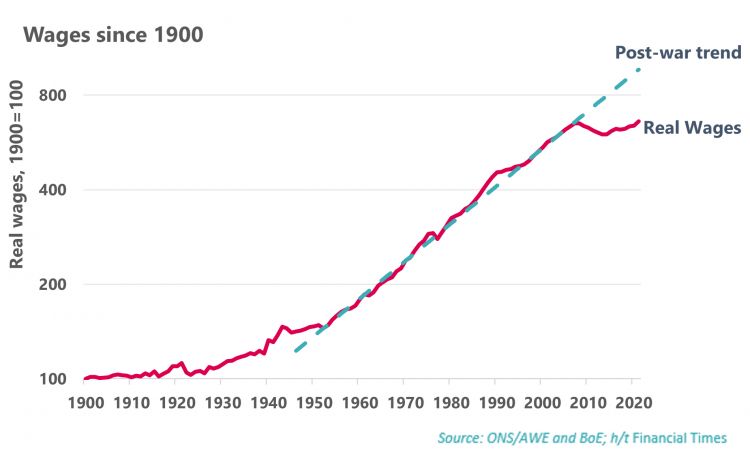

Recent progress on the minimum wage has been dampened by stagnant wage growth. But it is only since the financial crisis that wage growth has stalled. Workers are currently experiencing the longest and harshest pay squeeze in modern history. Real wages have fallen significantly behind the post-war trend. And with inflation currently on its way to 13 per cent13 , real pay is plummeting further. We are set to see the fastest fall in real wages for 100 years later this year.14

- 12 Low Pay Commission (2022) The National Living Wage Review 2015-2020 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1076517/NLW_review.pdf

- 13 Bank of England (August 2022) Monetary Policy Report https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2022/august-2022

- 14 The Guardian (11 Aug 2022) Biggest UK fall in real wages for 100 years looms, warns TUC https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/aug/11/biggest-uk-fall-real-wages-100-years-looms-tuc-inflation

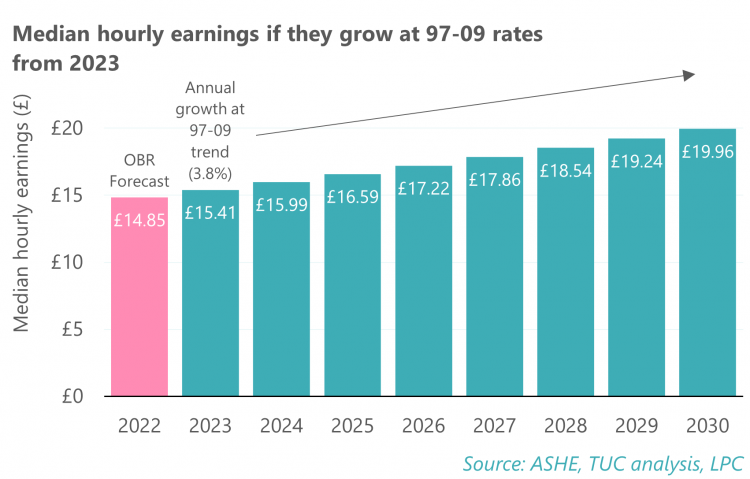

Workers need to see a return to normal or higher wage growth. This means a return to the levels of wage growth seen between 1997-2009 at the very least. Over this period nominal wages grew by an average of 3.8 per cent a year.

If wages had continued to grow at this rate, median wages would now be £3 an hour higher. The median wage would be £17.83 in 2022 rather than £14.85. Median hourly pay would have exceeded £20 by 2026. Even at a conservative estimate of returning to pre-financial crisis levels of wage growth from next year, we would achieve an hourly median pay of approximately £20 in 2030. In combination with a 75 per cent bite, this would establish a £15 minimum wage. But with the right political choices and active policy commitment we could get there much faster.

These illustrations of wage growth are conservative following over a decade of stagnation. Higher rates of sustained wage growth are needed to make up for the lost ground since the financial crisis.

And more wage growth is needed right now to sustain living standards in the face of high inflation. The latest figures show average total pay growth at 5.1 per cent in 2022 Q2.15 The Bank of England16 forecasts that nominal wage growth will be 5.25 per cent by 2022 Q4. This is more than wiped out by inflation which is forecast to rise to 13 per cent.

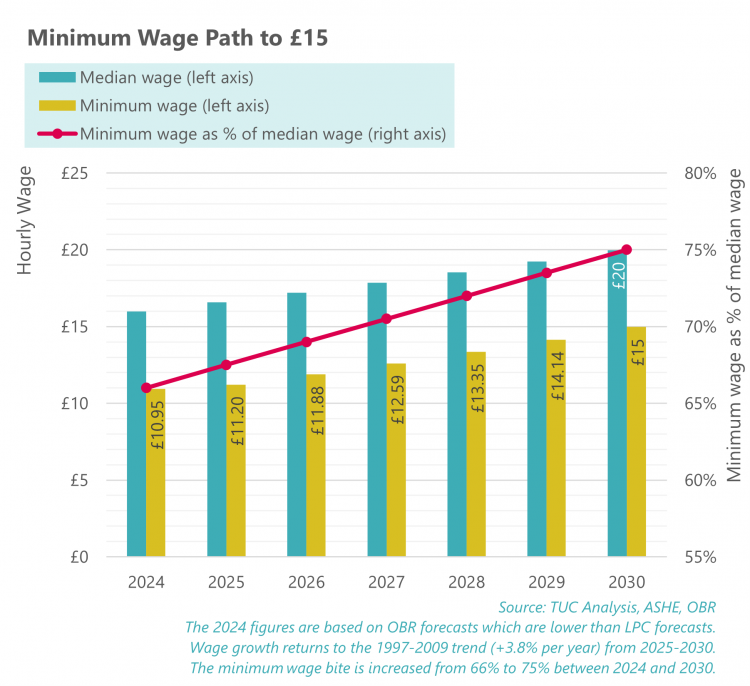

Charting a path to £15

The Low Pay Commission should be responsible for charting the path to a £15 minimum wage. Below we set out a conservative path based on:

- A minimum wage bite rising to 75 per cent of median wages

- Wage growth at normal pre-2010 rates of 3.8 per cent a year

- 15 ONS Average Weekly Earnings (April-June 2022)

- 16 Bank of England (August 2022) Monetary Policy Report https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy-report/2022/august-2022

Even this highly cautious estimate would deliver a £15 wage floor by the end of the decade. It is worth re-stating that this is based on conservative ambitions for wage growth. We need higher sustained wage growth to make up lost ground since the financial crisis. And wages need to grow faster right now to sustain living standards in the face of high inflation. Higher wage growth should deliver a £15 minimum wage sooner, and the TUC believes we should reach £15 as soon as possible.

For example, wage growth of 5 per cent a year, alongside achieving a minimum wage rate that is worth 75 per cent of average wages, would deliver a £15 minimum wage by 2028. A recovery to pre-crisis wage levels would deliver it by 2026. The timeline should adapt to prevailing economic circumstances so that £15 is delivered as soon as possible and of course many companies who currently pay their workers at or around the level of the national minimum wage could afford £15 now.

In practice, the Low Pay Commission should be responsible for the path based on consultation and negotiation through its social partnership model with unions, business, and independent academics. It should mould make recommendations based on economic circumstances, including the level of wider wage growth, labour market conditions, business conditions, and other evidence. It should continue to make recommendations with an eye on achieving the upcoming target. This model provides a safe mechanism to push the minimum wage higher. The Low Pay Commission can recommend an ‘emergency brake’ if it believes the target needs to be delayed. Even through the pandemic, the brake has not proven necessary.

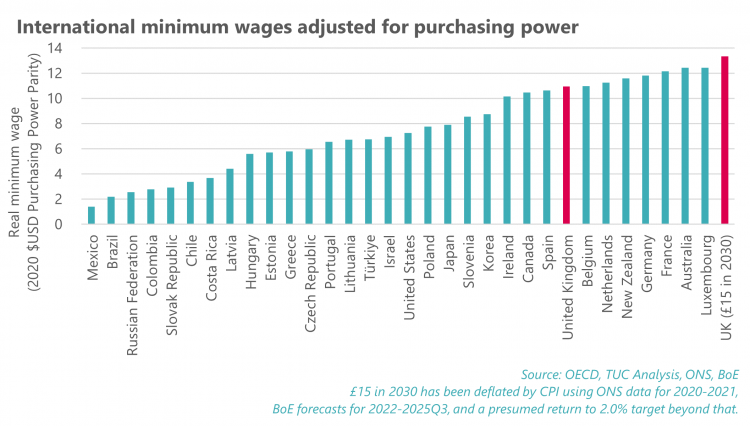

International minimum wage comparisons

The UK minimum wage was introduced at levels lower than many similar countries. 17 Over the last 20 years the UK has climbed the minimum wage rankings. The 2024 target continues our journey to among the highest minimum wages in the world. The UK has pushed the boundaries of the minimum wage and demonstrated that higher minimum wages are possible. We have demonstrated that higher minimum wages lead to higher pay in the lowest-paid jobs, and that this can be achieved without negative impact on employment levels.18

- 17 Resolution Foundation (29 March 2019) Top of the Charts: Minimum Wage 20th anniversary special https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/comment/minimum-wage-20th-anniversary-special/

- 18 Low Pay Commission (2022) The National Living Wage Review 2015-2020 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1076517/NLW_review.pdf

A £15 minimum wage will continue this journey. Recent international comparisons show that the UK has a relatively high minimum wage, but by no means the highest. The OECD produces comparisons which adjust for differences in purchasing power. The most recently published data from 2020 shows the UK behind Australia, France, Germany, New Zealand and some other of our European peers.

We have plotted £15 in 2030 on this chart, using inflation forecasts to deflate it to 2020 prices. This shows that our target is likely to make our minimum wage one of the very highest. However, as we build the evidence that minimum wages work, other countries are likely to also press ahead with increases so we will need to keep up. Germany is increasing the minimum wage by 20% this year. We should be looking to lead the way as we have done by pioneering the use of a bite target.

Our target is underpinned by a 75 per cent bite. Our bite target is ambitious but there are other countries close to this, including New Zealand (72%)19 , Chile (72%), Portugal (65%) and South Korea (62%).20 In lower income countries there are examples of even higher bites, but these countries have very different wage distributions to the UK. For example, Colombia has a bite of 92 per cent. Analysis by the ILO21 finds that the average bite in developed and emerging economies is 55 per cent, and in developing countries is 67 per cent.

Our approach will continue testing the boundaries of the minimum wage. The UK has pioneered the use of a target-based model underpinned by the social partnership of the Low Pay Commission. This creates a safe environment to make annual increases towards the target, assessing the impact as we go. It has the potential to position the UK at the forefront of minimum wage policy.

Young workers

The minimum wage currently has lower rates for young workers. The TUC’s view is that there should be no discrimination based on age. Young workers should be paid the same wage for the same job as those older than them.

There are currently three youth rates for workers. The 21-22 rate is in the process of being absorbed into the main rate. The evidence shows that this can be done without negative effects on employment.22 This should happen as soon as possible as there is strong evidence that the experience of these workers is like those older than them.

The rates for those aged 16-17 and 18-20 should also be increased so that they converge on the main rate with a goal of eventually abolishing youth rates. This should happen alongside progress towards a £15 minimum wage. The Low Pay Commission should monitor the impacts of these increases.

Pay differentials

It is sometimes argued that a higher wage floor could compress pay differentials between the lowest paid and those immediately above them in the pay distribution. Our plans seek to increase wages for all workers. The median wage and the minimum wage need to grow if we are to deliver a high wage economy. Higher wage growth creates more room for differentials as the cash headroom increases. A £20 median wage and £15 minimum wage has more room to accommodate progression than a pay scale squashed by wage stagnation.

There is also evidence that higher minimum wages spill over into higher pay further up as firms seek to maintain pay differentials. The Low Pay Commission says “in addition to the 1.6 million workers (7 per cent of jobs) paid the NLW in 2019, we estimate that up to a further 6.7 million jobs (28 per cent of jobs) were paid more than they otherwise would have been.”23

Collective bargaining and fair pay agreements

A statutory minimum wage is an effective tool for eliminating low pay. But workers can achieve higher wage growth where they are able to collectively bargain through trade unions. This can be seen today as unions are agreeing pay deals that take workers in sectors like retail above the minimum wage.

Fair Pay Agreements should be used to bring together employers and unions on a sector by sector basis to agree minimum levels of pay for similar kinds of work. This will enable workers in these industries to move to a £15 wage floor quicker than the statutory minimum wage.24

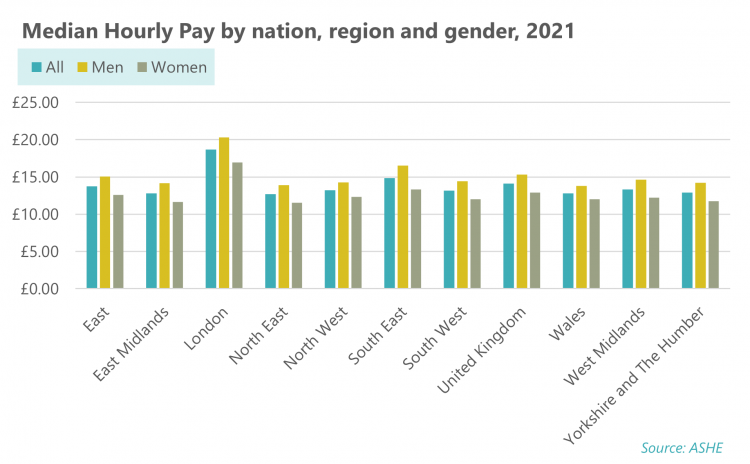

Levelling Up and closing the Pay Gap

The analysis in this paper is based on the median hourly wage reaching £20 an hour. It is worth noting that in 2021 this was already below the median hourly wage for men based in London (£20.32). We should lift pay across our regions and nations, and close the gender pay gap so that the overall median grows to this level. A higher minimum wage will also be important for delivering higher pay for Black and disabled workers, who are often concentrated on low pay.

- 19 New Zealand Government (April 2022) Minimum Wage Review 2021 https://www.mbie.govt.nz/dmsdocument/19602-minimum-wage-review-2021-cabinet-paper-proactiverelease-pdf

- 20 OECD figures for Chile, Portugal and South Korea, 2020.

- 21 International Labour Organization (2020) Global Wage Report 2020–21 (p110) https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_762534.pdf

- 22 Low Pay Commission (November 2019) A review of the youth rates of the National Minimum Wage https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attach

ment_data/file/845076/A_Review_of_the_Youth_Rates_of_the_National_Minimum_Wage.pdf - 23 Low Pay Commission (2022) The National Living Wage Review 2015-2020 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1076517/NLW_review.pdf

- 24 TUC (2019) A stronger voice for workers – how collective bargaining can deliver a better deal at work https://www.tuc.org.uk/blogs/stronger-voice-workers-how-collective-bargaining-can-deliver-better-deal-work

Recommendations

A plan for wage growth

The government must deliver:

- A macroeconomic approach which boosts demand and creates growth

- A plan to strengthen and extend collective bargaining across the economy including introducing fair pay agreements to set minimum pay and conditions across whole sectors

- A life-long learning and skills strategy to fill labour shortages, boost productivity and so workers can update their skills throughout their working life

- Corporate governance reform to prioritise long-term sustainable growth, rather than short-term focus on shareholder returns

- Industrial and trade policies to promote good jobs and ensure that businesses compete on a level playing field

- Making decent jobs a requirement of all government spending and procurement.

A plan for a £15 minimum wage

- The government and Low Pay Commission should set out a plan to achieve a £15 minimum wage.

- The government should set a target for the national minimum wage to reach 75 per cent of median wages.

- The government should deliver a return to normal pay growth. Wages need to grow by at least 3.8 per cent a year, as they did from 1997-2010.

- The Low Pay Commission should chart a prospective path to £15. The path should be underpinned by a return to pre-crisis wage growth of at least 3.8 per cent a year.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox