Jobs and pay monitor - Why we need a pay rise

After the longest wage squeeze for 200 years, working people need an approach to inflation that protects jobs and that helps protect pay and living standards.

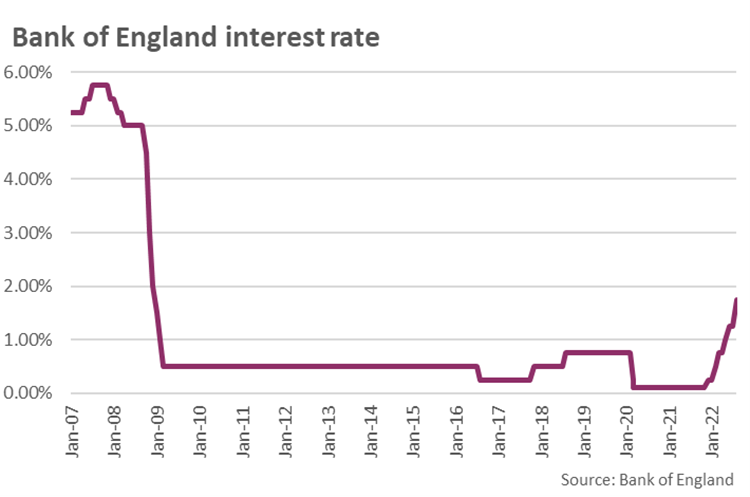

The Bank of England has responded to rising inflation caused by energy issues and problems in global supply chains with interest rate hikes that have taken the interest rate from 0.1 to 1.75 per cent over nine months.

They now predict that the impact of this will be a long recession and the loss of one million jobs.

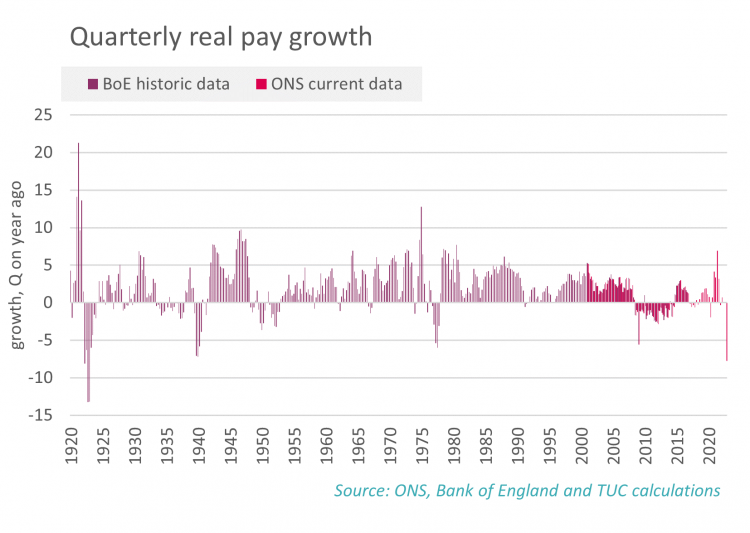

At the end of this year, workers are expected to face a hit to real pay of minus 7.75 per cent – TUC analysis of quarterly figures shows this will be the steepest decline for exactly a century. The longest pay decline since the Napoleonic wars is not only unended, but severely intensified.

Business had tremendous support from taxpayers during the pandemic. They should now help to counter inflation with greater profit restraint – especially energy firms. And the government must do more to get pay rising, starting with decent pay rises for public servants, a higher minimum wage and stronger right for working people and their unions to bargain for fair pay.

This edition of our regular jobs and pay monitor sets out the arguments to show that workers can have pay rises without this leading to further inflationary pressure.

Why we need a pay rise: in brief

- Prices aren’t rising because workers are getting a pay rise. They’re rising because the impact of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine have pushed up the price of energy and some basic goods. In fact, inflation is now rising by more than double the rate of pay growth; by the end of this year workers real pay will be falling by a staggering 7.75 per cent. That’s on top of the longest wage squeeze for 200 years. This isn’t a wage-price spiral, it’s a real pay disaster.

- In the face of crisis, those who’ve got power are protecting their incomes: business are making sure they don’t take a hit to their profits; bankers are seeing their bonuses soar; and the wealthy have made sure that as real pay stagnates, their wealth goes on rising. Pay rises don’t need to lead to price rises if companies rein in their profits.

- The biggest threat we face now is that of recession: the Bank of England are predicting that the UK will spend all of 2023 in recession, and over a million job losses. That’s not inevitable – if workers get a decent pay rise they can help protect spending and the economy.

- A decade of falling real pay shows our economic policy isn’t working. What we need now is a strategy to deliver decent pay and grow the economy. Forcing workers to take the hit while the wealthy increase their wealth has led us into crisis after crisis. We need a new approach the puts workers ahead of wealth and a productive economy ahead of an extractive economy. That means investing in UK workers, in the secure green energy supply we need, and in boosting jobs in the UK – in the public and private sector. Workers deserve better than another decade of pay cuts.

Rather than pushing down incomes for workers the UK government must:

- Set out a plan to deliver good jobs across the country, including investing in the transition to net zero, and high-quality manufacturing jobs

- Invest in public services and public servants, delivering real pay rises to stem the crisis in recruitment and retention

- Reverse a decade of cuts to skills policy and deliver tailored training to every worker

- Deliver decent levels of social security and pensions,

- Increase the minimum wage; and most importantly

- Give workers the bargaining power they need to get their fair share of wealth, starting by introducing fair pay agreements across the economy. This will ensure that everyone benefits from negotiations between workers and employers, setting a minimum floor for terms and conditions across the whole economy.

Why we need a pay rise: further evidence

1. Prices aren’t rising because workers are getting a pay rise. They’re rising because the impact of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine have pushed up the price of energy and some basic goods. In fact, inflation is now rising by more than double the rate of pay growth; by the end of this year workers real pay will be falling by a staggering 7.75 per cent. That’s on top of the longest wage squeeze for 200 years. This isn’t a wage-price spiral, it’s a real pay disaster.

Inflation

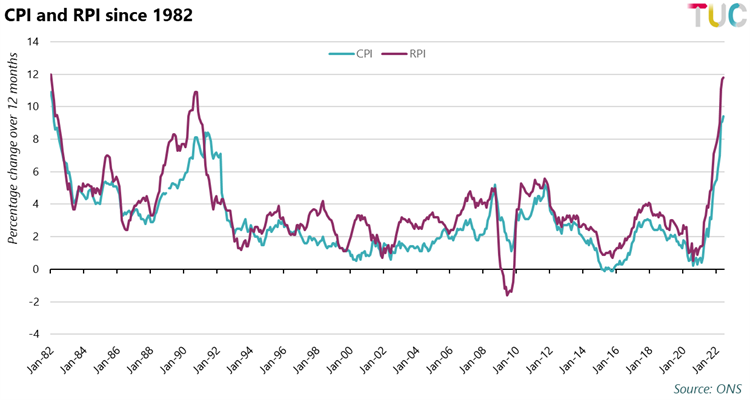

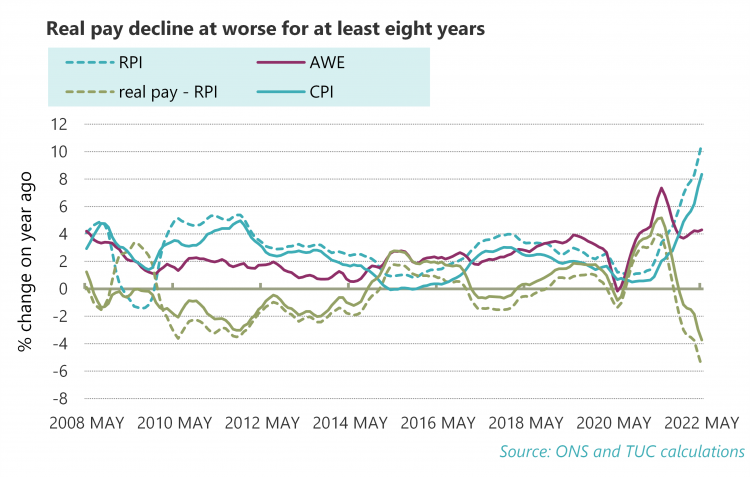

Inflation has been rapidly rising over the past year and is now at a 40-year high. CPI currently stands at 9.4% and RPI is 11.8%.

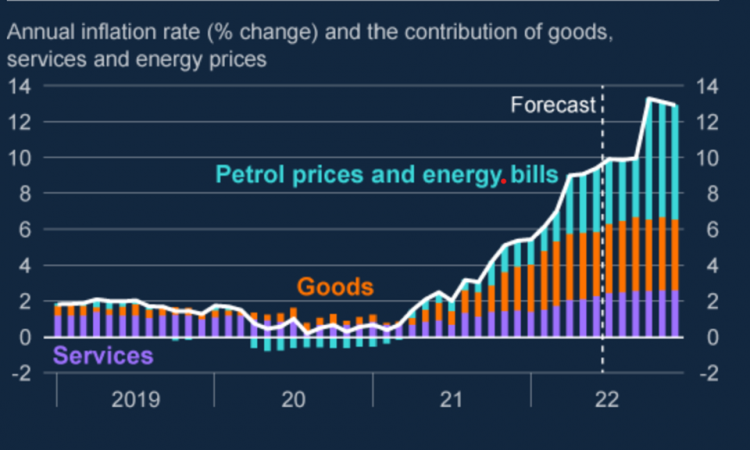

The main factors driving inflation are energy, fuel and food prices. The war in Ukraine has compounded the problems in global supply chains as pandemic lockdowns ended. In their latest (August) Monetary Policy Report, the Bank of England stress as a result of “materially higher gas prices stemming from the war in Ukraine, inflationary pressures in the UK and the rest of Europe have increased further” (p. 37). 1

. They report for the UK “a pickup in prices across a broad set of goods and services components within the overall CPI”– see their chart (of contributions) below. And they now predict that inflation will reach a peak of 13.3% in October 2022.

Nominal and real pay

Earlier this year in May at the House of Commons Treasury Committee, Andrew Bailey and his colleagues repeatedly stated that the labour market accounted for only 20 per cent of the above target inflation,2 . and the Bank of England have previously emphasised the inability of action taken only in the UK to deal with global cost inflation.

In their latest assessment, they claim “the strength of nominal pay growth” is playing a role in the increase inflation of the service sector, “since labour costs tend to make up a large proportion of the costs for service sector firms”. But overall there is no evidence of a wage price spiral, that has been so prominent in much recent commentary.3 . Regular pay growth is now 4.3 per cent, 5.0 per cent in the private sector, and 1.8 per cent in the public sector. Even the Bank’s estimates for underlying pay growth (i.e. adjusting for distortions caused by the furlough scheme) are only 4.5 per cent which might rise to 5.5 per cent. 4 .

In real terms, the latest official figures earnings figures mean real pay declines of 3.7 per cent on CPI and 5.7 per cent on RPI. These are the worst outcomes since the present data began in 2000.

- 2 “Q434 Sir Dave Ramsden “… 80% of the overshoot is to do with first round effects—the shocks that have hit the economy—so you are talking about the behaviour of firms and bargainers in the labour market only for the other 20%. You are talking about a very small part of the inflation overshoot that we have seen”: https://committees.parliament.uk/event/13558/formal-meeting-oral-eviden…

- 3 Eg The Economist, ‘The Bank of England is determined to prevent a wage-price spiral’, 27 Jan. 2022: https://www.economist.com/britain/2022/01/27/the-bank-of-england-is-det…

- 4 Monetary Policy Report, August 2022, Bank of England, pp. 57-8.

And it gets worse: the Bank’s headline forecasts for the fourth quarter of this year show CPI inflation at 13.0 per cent and nominal pay growth of 5.25 per cent, this means real pay will decline by 7.75 per cent. This is not a wage price spiral this is a real pay disaster.

This scale of pay decline is almost unprecedented, on quarterly figures amounting to the largest decline for exactly a century. The chart below shows growth in real pay back to 1920. Real pay has fallen by more on only one occasion, a decline of 13.3 per cent in 1922Q4 – as the post First World War pay and price inflation went sharply into reverse. The only other comparable figure was 7.2 per cent in 1940 Q1.

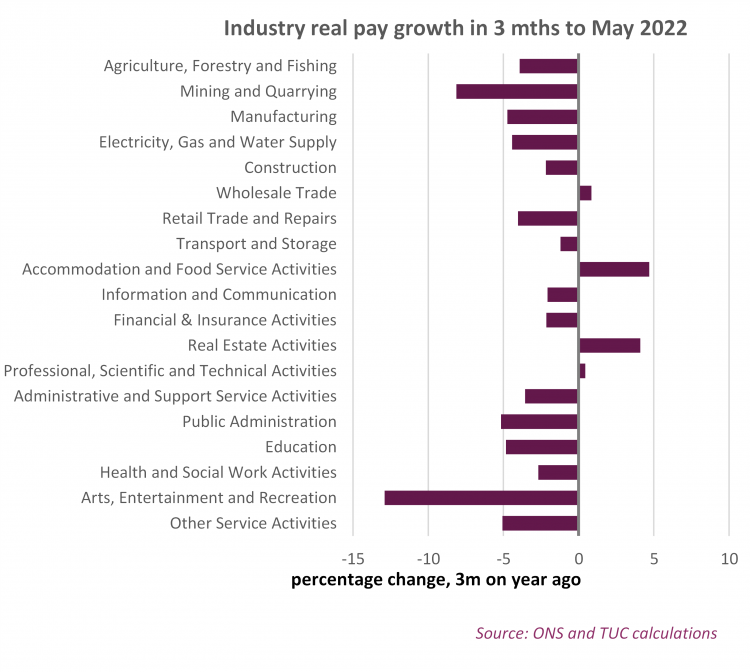

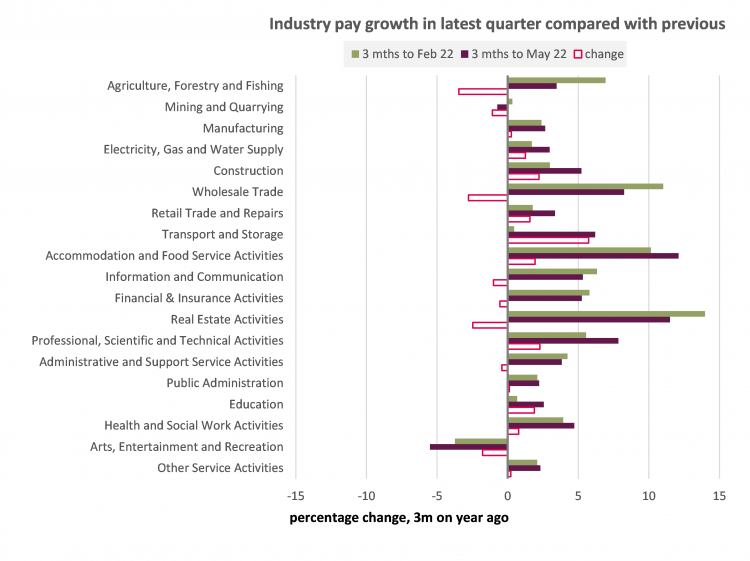

Industry pay

By industry, real regular pay growth is negative across most industries, with positive growth the exception not the rule. Real regular pay is falling in all but hospitality and real estate, with marginal gains in wholesale trade and professional and business services.

Nominal regular pay growth needs to pick up pace to protect real wages, but most industries are not seeing enough of an increase in the rate of wage growth. Wage growth is slowing in as many industries as it is rising.5

- 5 Leaving aside small changes from 0 to +/- 0.5, there are seven up and seven down. [/fn The only three industries with both pay growth over 5 per cent and accelerating pay growth are transport and storage, accommodation and food, and professional, scientific and technical.

But the Bank are less operating on the basis of pay growth now, and instead concerns about pay in the future. Their arguments are discussed in the section (3).

2. In the face of crisis, those who’ve got power are protecting their incomes: business are making sure they don’t take a hit to their profits; bankers are seeing their bonuses soar, and the wealthy have made sure that as real pay stagnates, their wealth goes on rising. Pay rises don’t need to lead to price rises if companies rein in their profits.

After in February the Governor’s lecturing workers to exercise pay restraint, only late in the day did the Bank concede that firms could instead put up pay and take a hit on profits. 6 But then in August he doubled down and suggested those workers with enough power to secure higher wage increases were disadvantaging those unable to do so. 7

Decent pay deals secured by trade unions should be celebrated, and we will continue to fight for union recognition and more widespread collective bargaining. But in the meantime the Governor turns a blind eye to those with the greatest power who are making the most out of the crisis: city workers, profiteering companies and the wealthy.

Bonuses

Total pay in the ‘finance and insurance’ sector including bonuses was 13.6 per cent in the year to Mar-May 2022, down marginally from the recent peak of 15.4 per cent over Jan-Mar. In March 2022 city bonuses were at their highest cash level on record. The gap between pay including bonuses and regular pay is also at historically large levels and was a record 2.8% in March.

As well as big rewards for the city, there is growing evidence that firms are using bonuses rather than consolidated pay rises – a fuller discussion was included in our previous Jobs and Pay Monitor. 8

Companies are protecting their profit margins as prices rise.

In the Monetary Policy Report the Bank of England note firms reporting “that they expect to increase their selling prices markedly, following the sharp rises in their costs, to protect their margins” (eg p. 8). Moreover, they go as far as: “Business services firms continue to report significant cost pressure, especially higher wages, and report being able to increase prices by more than normal given strong demand” (p. 59, TUC emphasis). Even on the basis of the Bank’s own theory, pay can rise without causing inflation if companies rein in their profits. And both pay and profits could rise if productivity improved, though businesses have proved unwilling to invest in improving their productivity over the last decade.

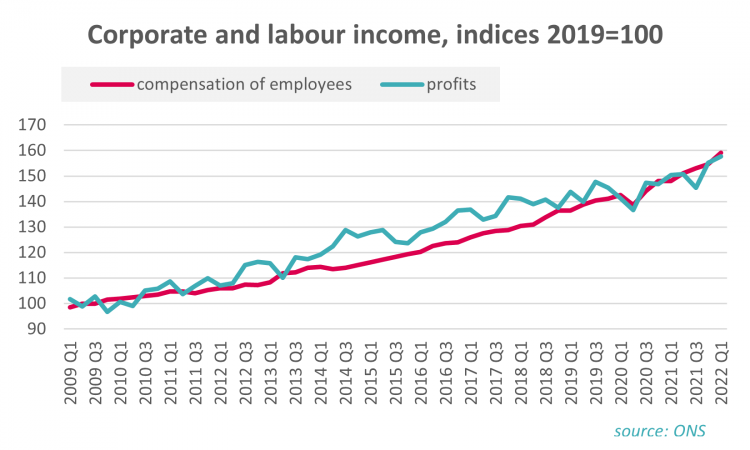

The official ONS measure of profits (or gross operating surplus) across the whole economy is produced as a component of the income measure of GDP, along with compensation of employees that captures total labour income (i.e. employment as well as pay, also including employers’ contributions to pensions). These figures should be treated with a lot of caution, as they are often revised.

In the latest figures ONS show a rise of profits of 4.9 per cent in the year to 22q1, with compensation of employees up by 7.4 per cent. This profit figure has been revised down from the previous estimate of 8.1 per cent, and is now not greatly out of line with regular pay growth of 4.3 per cent – though further revisions are likely.

The chart below compares labour income and profits since the trough of the global recession in 2009. There is a sense throughout of profits running ahead of labour income, but ground was lost from the end of 2019 (just ahead of the pandemic, when global fragilities were re-emerging) and now over the latest half year firms attempting to recapture that ground.

Research looking specifically at FTSE companies, rather than across the whole economy (as in the ONS figures), has shown strong profit growth in 2021. 9

- Unite show a rise of 73% on profit margins in 2021 compared to 2019, up to 9.1% from 5.3%; they also show strong gains when energy companies are excluded.

- IPPR analysis shows an increase of 32% on average profits between 21Q2-21Q4 and the three years before pandemic

It is clear that some companies are experiencing very large profit margins, though there is some uncertainty around how widely these are spread – with IPPR noting in particular the biggest gains for firms selling basic materials. Some increases may reflect firms making up for lower payments in 2020.

Unite also report analysis carried out by Bank of England ‘Agents’ that was included in the previous (May) Monetary Policy Report, and summarised as follows in the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) minutes:

A special survey on pricing and profit margins conducted by the Bank’s Agents suggested that firms expected significantly more upwards pressure on prices over the next twelve months than the previous twelve months. Higher labour costs, utilities prices, and the costs of shipping and raw materials were frequently cited as factors pushing up on inflation over the next year. Around half of survey respondents considered that it was easier than normal to pass these cost increases through to prices. Close to 40% of companies had described their margins as unsustainably low at present, but three-fifths of those firms had anticipated rebuilding their margins to sustainable levels over the next twelve months.

While these data are complex, it’s clear that while workers are expected to take a pay cut, firms are protecting their profits.

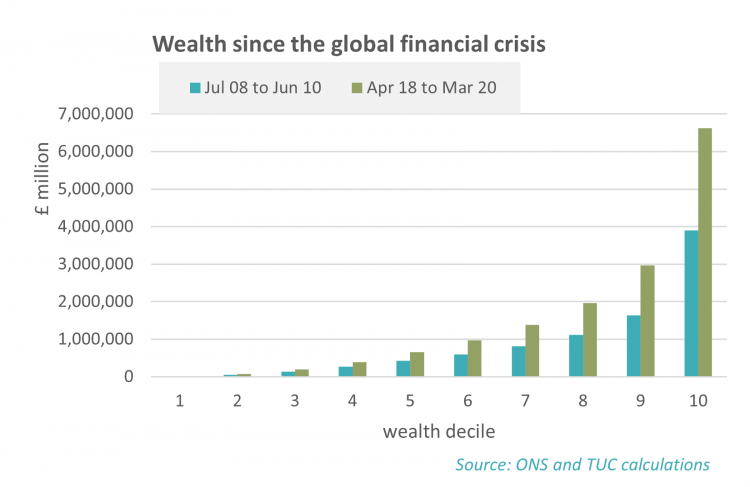

Wealth

Workers are repeatedly told that the latest crisis (not least the current inflation) means they have to face up to being poorer, or that they have lived beyond their means. But this has not been the case for wealth.

Over the past decade under austerity and quantitative easing policies workers did get poorer. The analysis produced for the TUC Britain Demands Better demonstration on 20 June showed that working people lost nearly £20,000 in real earnings between 2008 and 2021 as a result of pay not keeping pace with inflation. Since then the longest pay squeeze since the Napoleonic wars has been severely intensified. On the other hand over broadly the same period the ONS estimate that wealth increased by £6 trillion to £15.2 tb in 2018/20 from £8.9 bn in 2008/10.10

Moreover wealth is distributed much more unequally than income. As the chart below illustrates, more than half of the gain in wealth accrued to the top ten per cent. The bottom five deciles enjoyed only 7% of the gain, and are still left with miniscule levels of wealth.

- 9 The samples are similar: Unite FTSE 350 company accounts and IPPR 308 largest non-financial firms. Unite the Union, ‘Corporate profiteering and the cost of living crisis’, 17 Jun. 2022: https://www.unitetheunion.org/news-events/news/2022/june/new-unite-investigation-exposes-how-corporate-profiteering-is-driving-inflation-not-workers-wages/; Institute for Public Policy Research, ‘Prices and profits after the pandemic’, Chris Hayes and Carsten Jung, Jun. 2022: https://www.ippr.org/files/2022-06/prices-and-profits-after-the-pandemic-june-22.pdf

- 10 This is based on the ONS ‘wealth and assets survey’ that assesses wealth across property, financial assets, pensions and ‘physical’ (corresponding to goods like cars, TVs and sofas).

3. The biggest threat we face now is that of recession: the Bank of England are predicting that the UK will spend all of 2023 in recession, and over a million job losses. That’s not inevitable – if workers get a decent pay rise they can help protect spending and the economy.

At their August meeting the MPC raised rates by 0.5% to 1.75% by a majority of 8-1. This was the biggest interest rate hike in 27 years. Rates are now the highest since 2009 when rates were reduced in the wake of the global financial crisis. The rate rise was accompanied by a forecast of a severe recession, from 2022 Q4 lasting 5 quarters – longer than the global recession of 2008-09 and one comparable in severity to the early 1990s recession. For Chris Giles, economics editor of the Financial Times, “The key takeaway is that [the Bank of England] thinks a recession is inevitable and necessary to bring down inflation”.11

The MPC rate hikes followed the Federal Reserve in the US raising rates by 0.75 per cent on 27 July, so that the Fed Funds rate stands at a range of 2.25 per cent to 2.5 per cent. In the Eurozone, the ECB raised interest rates for the first time in more than 11 years by 0.5 per cent to 0 per cent, ending its era of negative rates.

Ahead of recession, GDP data over the next two quarters will be erratic. After growth falling in both March and April, by 0.1 per cent and 0.3 per cent respectively, it rebounded by 0.5 per cent in May 2022. On quarterly numbers, the Bank reckon GDP in Q2 will be down 0.2 per cent and then Q3 up 0.4 per cent. This seesawing before the more substantial downturn follows in part because of business shutdowns across the Platinum Jubilee holiday in June. GDP is expected to then fall negative in the last quarter of 2022, and recession is expected to continue for five quarters.

The crisis is already obvious in measures of consumer confidence, with consumer spending beginning to fall as the cost-of-living crisis bites. The UK consumer confidence index fell 2 percentage points to –40% in May according to research company GfK, its lowest since records began in 1974 – almost 50 years ago.

Bank of England narrative and argument

Higher prices mean falling real wages and a record fall in household disposable incomes. Falling incomes therefore mean falling spending and recession – labelled a ‘key judgement’ by the Bank of England, who say “given the sharp decline in household real incomes, consumer spending falls over the next year and the UK economy enters recession”.

A forecast rise in the unemployment rate to 6¼ per cent in 2025, translates to an additional one million workers without work and total unemployment of 2.3 million.

Given these dire conditions as well as the real wage disaster, the savage rise in interest rates is difficult to fathom. The action is motivated instead by concerns of ‘second round effects’ and inflation outcomes becoming ‘embedded’.

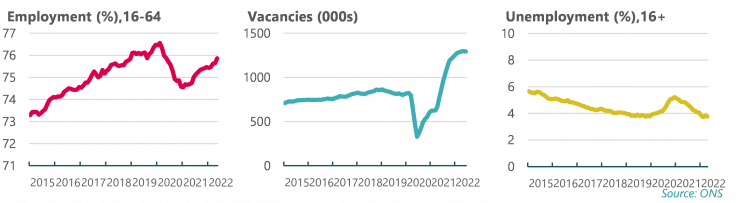

The Bank focus on the so-called ‘tight labour market’. High vacancies, low unemployment and high inactivity are meant to indicate increased future wage inflation. The charts below illustrate key features. While unemployment is back at its level of 3.8 per cent before the pandemic, employment is still 0.7 percentage points below the pre pandemic rate – higher inactivity (not shown) accounts for the difference.

Overall the suggestion is there are not enough workers to do the work that needs to be done, and this is reflected also in vacancies data running greatly higher than normal levels. As set out above, firms have been able to raise prices to account for higher costs – not only of wages, but also of materials. But with rising prices already hitting consumer spending, the period in which firms can rise prices looks set to be a vanishingly small window as firms look down the line and see spending and demand collapsing – even before further interest rate rises.

Certain conditions may be exceptional, but in more general terms the Bank have repeatedly for over a decade feared pay rises in theory that have not materialised in practice.

- Above all it has been repeatedly shown that falling rates of unemployment in the UK have not lead to higher pay growth, instead they have been supported by low pay growth. This should not be the natural state of affairs, but it is the reality engineered by policymakers in the post global financial crisis world.

- Increases in inactivity is a feature of all recessions and can quickly reverse when economic activity picks up pace.

In fact the latest labour market figures point to a potential reduction in inactivity already, with numbers of 16-64 reducing by 225,000 since the start of the year. In parallel over the same period, vacancies have levelled off at 1.3 million.

What the economist Servaas Storm argues of the US seems no less true of the UK: “wage growth barely manages to partially follow (not leading) inflation, but it is quite a stark example of blaming the victim”. 12

4. A decade of falling real pay shows our economic policy isn’t working. What we need now is a strategy to deliver decent pay and grow the economy. Forcing workers to take the hit while the wealthy increase their wealth has led us into crisis after crisis. We need a new approach the puts workers ahead of wealth and a productive economy ahead of an extractive economy. That means investing in UK workers, in the secure green energy supply we need, and in boosting jobs in the UK – in the public and private sector. Workers deserve better than another decade of pay cuts.

For forty years the interests of wealth have been prioritised over the needs of workers. The labour share in the UK (and around the world) has fallen significantly by 10 percentage points of GDP over the past 60 years, from 59 per cent in the two decades after the Second World War to 48 per cent in the five years ahead of the pandemic.13

Productive activity has given way to speculative activity, and the economy has become dangerously vulnerable to financial crisis.

Workers are repeatedly told that they must bear the consequences of crises on their shoulders. But in the last decade workers were made poorer while quantitative easing increased asset prices and the value of wealth soared.

This outcome has made worse the economic dangers when there is excessive money in the hands of the few and too little in the hands of the many. Looking at the inflation debate in this broader context, former US Secretary of Labour Robert Reich warned last year:

“Here’s the thing. The wealthy spend only a small percentage of their income – not enough to keep the economy churning. Lower-income people, on the other hand, spend almost everything they have – which is becoming very little. Most workers aren’t earning nearly enough to buy what the economy is capable of producing”.14

Moreover, excess wealth is constantly seeking new outlets for capital gain, fostering speculation in residential and commercial property, undue emphasis on high-tech companies (the FAANGs so called), and hot money flows to emerging market economies.15

These excesses mean asset prices are vulnerable to a change in financial conditions – it is too high wealth and too low wages not high wages that are creating economic vulnerability.

And there are widespread signs of this vulnerability in financial markets. While equity prices rebounded a little over July, at the middle of the year US shares were in so-called ‘bear market’ territory, having declined by 20 per cent; high tech shares were down 30 per cent. At present global commodity prices have seen sharp falls on recent peaks, for example copper is down one third, lumber two thirds and brent crude one fifth. Likewise share prices for a number of important asset managers are heavily down (e.g. Jupiter by 50%, Janus Henderson by 40%) with repercussions for pension funds and wealth management.16

The promise to ‘build back better’ after the pandemic must be made good. In 2020 the boss of the IMF Kristalina Georgieva called out a Bretton Woods moment, 17 “to fight the crisis today – and build a better tomorrow”. A new approach must put workers ahead of wealth and a productive economy ahead of an extractive economy. That means investing in UK workers, in the secure green energy supply we need, and in boosting jobs in the UK – in the public and private sector. Workers deserve better than another decade of pay cuts.

The post war Attlee government is a relevant precedent. Seeing clearly “too much economic power in the hands of too few men”, in their Manifesto they urged “Production must be raised to the highest level and related to purchasing power”. Their programme of social reform was underpinned by this redistribution; a productive economy with full employment was facilitated too by the Bretton woods arrangements permitting countries to focus on domestic priorities. Public debt of 250% of GDP was rapidly turned around because the labour orientation proved better for a stronger economy.

Rather than pushing down incomes for workers the UK government must:

- Set out a plan to deliver good jobs across the country, including investing in the transition to net zero, and high-quality manufacturing jobs

- Invest in public services and public servants, delivering real pay rises to stem the crisis in recruitment and retention

- Reverse a decade of cuts to skills policy and deliver tailored training to every worker

- Deliver decent levels of social security and pensions,

- Increase the minimum wage; and most importantly

- Give workers the bargaining power they need to get their fair share of wealth, starting by introducing fair pay agreements across the economy. This will ensure that everyone benefits from negotiations between workers and employers, setting a minimum floor for terms and conditions across the whole economy.

- 12 Inflation in a Time of Corona and War | Institute for New Economic Thinking (ineteconomics.org)

- 13 TUC (2022) Jobs and recovery monitor, bonuses https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-monitor-bonuses

- 14 ‘The problem isn’t ‘inflation’. It’s that most Americans aren’t paid enough’, Robert Reich, Guardian, 13 Aug. 2021.

- 15 See the TUC submission to the Lords Economic Affairs Committee enquiry on QE: https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/23786/html/

- 16 ‘European asset managers prepare for turbulent second half of 2022’, Financial Times, 30/31 July 2022: https://www.ft.com/content/abc8a2f3-4f4d-4ef0-ab04-a24b8fde6e51

- 17 'A New Bretton Woods Moment’, October 15, 2020: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/10/15/sp101520-a-new-bretton-woods-moment

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox