Racial inequalities in health and social care workplaces

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) exists to make the working world a better place for everyone. We bring together more than 5.6 million working people who make up our 50 member unions. We support unions to grow and thrive, and we stand up for everyone who works for a living. Trade unions have been at the forefront of the response to the crisis, arguing for action to support jobs and the self-employed, better sick pay and social security, and measures to protect safety at work.

Our unions ensure working people have a voice at work. Before and during the pandemic, our trade unions and their thousands of unions reps will have been speaking on behalf of members, and by extension non-members, in the workplace about health and safety, pay, racism and more. Hundreds of thousands of workers across the NHS and in social care are members of our affiliated trade unions. Many more will benefit from the role of unions in these workplaces.

Trade union access to workplaces is important to ensure workers understand their workplace rights. Trained union reps support workers to understand the rights and assist them if there is a problem.

Within the NHS, there are structures to facilitate trade union access to workplaces and workers, including facility time and speaking to staff at inductions. This is delivered through trade union recognition and collective bargaining arrangements. However, when NHS services are outsourced, the provision for these arrangements does not necessarily follow for outsourced workers.

Outsourcing and casualisation allows end employers to outsource their employment responsibilities, leaving workers with minimal employment rights and security and undermining existing rights and terms and conditions. Such workers cannot challenge the end employer for any employment rights abuses. This restricts outsourced Black and ethnic minority (BME) workers and their unions’ ability to negotiate and bargain collectively, and challenge discrimination and unsafe working conditions where they occur.

This unsustainable and highly exploitative model of public service delivery must end.

1.We are interested in how lower-paid ethnic minority workers, including those in insecure employment, find out about and understand their workplace rights.

Are there any services or employers that you think provide good information and advice for workers, especially lower paid workers? (please answer below)

What helps and what gets in the way of ensuring lower-paid ethnic minority workers understand their workplace rights? (please answer below)

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) exists to make the working world a better place for everyone. We bring together more than 5.6 million working people who make up our 50 member unions. We support unions to grow and thrive, and we stand up for everyone who works for a living. Trade unions have been at the forefront of the response to the crisis, arguing for action to support jobs and the self-employed, better sick pay and social security, and measures to protect safety at work.

Our unions ensure working people have a voice at work. Before and during the pandemic, our trade unions and their thousands of unions reps will have been speaking on behalf of members, and by extension non-members, in the workplace about health and safety, pay, racism and more. Hundreds of thousands of workers across the NHS and in social care are members of our affiliated trade unions. Many more will benefit from the role of unions in these workplaces.

Unions, and their union reps, meet with management regularly. In the NHS, there are structures for this, in nations, regions and local trusts. They raise concerns, ask questions and negotiate with management on behalf of their members.

Collective bargaining is a public good that promotes higher pay, better training, safer and more flexible workplaces and greater equality. Unions play a vital role making sure that employment rights are respected and upheld by [1]:

i) Collective bargaining, negotiating improved terms and conditions for working people and putting in place mechanisms to remedy breaches of these terms and conditions where necessary

ii) Raising employers’ awareness of their employment responsibilities, including when new employment rights are introduced

iii) Resolving employment disputes using grievance and disciplinary procedures and the right to be accompanied

iv) Where merited, supporting members to take cases to employment tribunal

v) Supporting strategic cases which clarify legal duties and set the norms to be followed by employers in similar workplaces and sectors.

Trade union access to workplaces is important to ensure workers understand their workplace rights. Trained union reps support workers to understand the rights and assist them if there is a problem.

Within the NHS, there are structures to facilitate trade union access to workplaces and workers, including facility time and speaking to staff at inductions. This is delivered through trade union recognition and collective bargaining arrangements. However, when NHS services are outsourced, the provision for these arrangements does not necessarily follow for outsourced workers.

Outsourcing and casualisation allows end employers to outsource their employment responsibilities, leaving workers with minimal employment rights and security and undermining existing rights and terms and conditions. Such workers cannot challenge the end employer for any employment rights abuses. This restricts outsourced Black and ethnic minority (BME) workers and their unions’ ability to negotiate and bargain collectively, and challenge discrimination and unsafe working conditions where they occur.

This unsustainable and highly exploitative model of public service delivery must end.

The TUC and our affiliated unions want to see public ownership and insourcing s the default setting for public services. Joint and several liability laws should be extended so that outsourced workers can bring claims for employment rights abuses against any contractor, and all NHS outsourced workers should be employed on the same Agenda for Change terms and conditions as directly employed workers in the NHS.

The situation is similar in social care for outsourced workers. Where trade unions have been able to agree collective bargaining arrangements, or where these exist as part of local government structures, workers are more able to understand and exercise their employment rights. However, where they do not the fragmented nature of social care delivery, the number of employers and the high turnover of workers make it difficult to organise these workers and represent them. TUC analysis found residential care workers employed by the public sector typically stay in post more than three times longer than private sector workers.[2]

Since 2012/13, the percentage of the adult social care workforce employed by local authorities (where recognition and collective bargaining structures are in place and formalised) has fallen from 10% to 7%, a reduction of 37,400 jobs. Information from local councils cited outsourcing as a reason for this. [3]

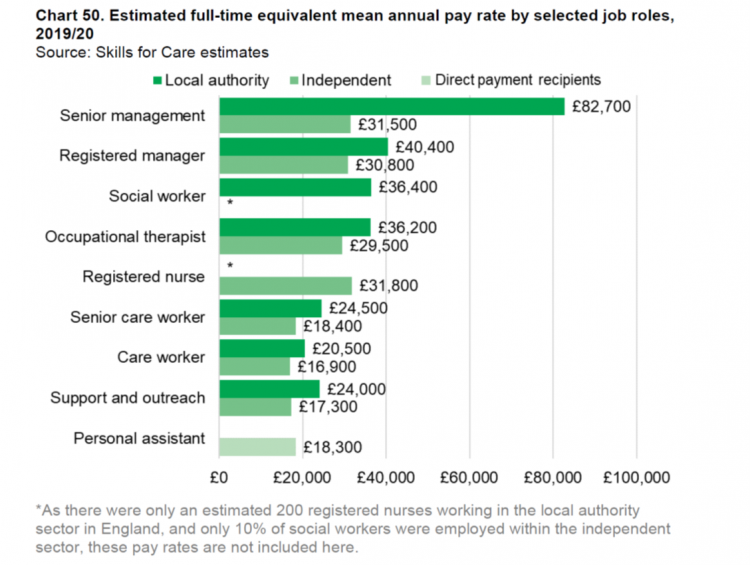

At the same time, full time equivalent mean annual pay for the adult social care workforce is higher for those employed by local authorities than those in the independent sector:

- £5,900 higher for senior care workers

- £3,600 higher for care workers

- £6,700 for support and outreach workers. [4]

The pandemic has laid bare just how vulnerable insecurely employed workers are to exploitation and how difficult it is to enforce the rights they have. It is more important than ever that insecure workers have a clear route to uphold their rights, have access to trade union representation and proper protections in place.

Even where workers have trade union representation, facility time and access to support workers is limited. Ensuring that unions can access the workplace to speak to members and workers would better help them understand their rights and have an opportunity to exercise them. Where organisations are broken up and services outsourced, union representatives should have the right to represent workers and access workplaces across the new structures.[1]

The NHS and social care sector rely heavily on migrant workers. It is important therefore that there is stronger regulation of labour market providers, and that NHS and social care commissioners ensure through procurement that workers are given information on their employment rights. This should include providing materials that explain workplace rights in an accessible format, translated if necessary. Information should make clear an individual’s:

- Terms and conditions of employment

- Name and contact details for the employer / end employer

- Employment rights and how to exercise them

- How to join a trade union

- Signpost to relevant regulatory bodies including the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) and Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitrary Service (ACAS)

The TUC has produced model guidance, working with union partners in the EU to deliver accessible information in multiple languages.[2]

2.We are interested in how someone’s immigration status affects how they are treated at work.

Are there any differences in treatment between those with a permanent right to work in the UK, and those with less secure immigration status? (please answer below)

Is there any difference in treatment between first generation immigrants, and British Born ethnic minorities? (please answer below)

In June 2019, 13.3% of NHS staff in hospitals and community services in England reported a non-British nationality.[3] Among doctors, the proportion is 28.4%. In March 2019, 20.1% of GPs in England qualified outside the UK, compared with 28.1% in North Central and East London and 7.3% in the South West. 16 per cent of the social care workforce are non-British nationals (247,000 jobs), the majority of which are non-EU nationals (134,000).[4]

Recent changes to immigration policy have had a huge impact on health and social care services where migrant workers are overrepresented in the workforce. The introduction of a points-based system and salary thresholds create profound issues for employers and workers in health and social care. The policy will have a significant impact on employers being able to recruit the staff they need. For example, care workers do not qualify under the ‘Skilled Workers’ route:

“For instance, the government’s immigration proposals which prevent migrant workers being recruited to roles paying below £25,600 pose a significant threat to migrant workers in social care. The salary thresholds are too high and ‘care worker’ is not listed as an eligible occupation under the ‘Skilled Workers’ route.” [1]

The characterisation of care work as unskilled goes to the heart of the staffing crisis facing the sector. Care work requires a range of skills, at all hours of the day and night, managing often challenging behaviour, delivering intimate personal care, undertaking risk assessments and dispensing medication, to name a few. Failure by the government to recognise and renumerate workers fairly for these skills, alongside poor terms and conditions, have led to a huge staff shortage in a sector where demand far outstrips supply.

For migrant workers, the reality is that issues of racism, discrimination and job insecurity are compounded by hostile migration policies. The government’s hostile environment policy, which set out to make staying in the UK as difficult as possible for those without leave to remain, has left many migrant workers vulnerable to employment rights abuses and unfair treatment at work. The threats of deportation faced by the Windrush generation, the uncertainty in the EU Settlement Scheme and the introduction of a points-based immigration system undermine migrant workers’ rights at work, leaves them feeling less secure about their immigration status and in turn reduces their ability to challenge unfair treatment at work.[2] As does the policy of tying workers’ employment to their migration status. If your migration status is tied to your employment, the power lies with employers and it can be hard to challenge unfair or exploitative practices.

The situation is for acute for workers subject to the ‘no recourse to public funds’ policy (NRPF). NRPF leaves affected migrant workers with no access to the social security system – a vital safety net for workers, particularly those who are insecurely employed. This creates precarity that prevents workers from speaking out and challenging unsafe, discriminatory or exploitative practices for fear of losing their job and falling into financial hardship.

Employers are aware of workers precarity and can use it to their advantage. Research by the Latin American Women’s Rights Service found migrant workers in outsourced jobs, including those in the care sector, were routinely subject to employment rights abuses including unlawful wage deductions and harassment.[3] These workers face huge barriers to challenging these practices and asserting their rights because of their migration status. Outsourced migrant workers reported to LAWRs that they had not been provided with any information about the employer, or any documentation to refer back to that explains their terms of employment. As a result, many are unaware of the name of their employer, how to get in touch with the company, and whether there are any mechanisms for redress. This is supported by the experiences shared by workers in the Unison and GMB contributions to the inquiry.

3.What processes are in place for lower-paid ethnic minority workers, including those in insecure employment, to have their voices heard in the workplace? For example, recognition of a union, ethnic minority staff groups and staff surveys.

Are these accessible and used by lower-paid ethnic minority workers?

Do you have any examples of where these have been used to change practice?

Trade union membership, and recognition of trade unions by employers, is a way for workers to have their voices heard and represent their concerns. This is important given the fears and insecurity faced by workers. Research by the OECD demonstrates the positive impact of unions. Unionised workplaces are fairer and safer than non-unionised workplaces.[4]

Within the NHS, social partnership forums allow for this and unions and the employer meet regularly to share concerns and address issues. Despite the lack of a formal body in social care, trade unions have been able to improve practice on behalf of members, most notably in calling for sick pay for workers isolating during Covid-19 leading to the ‘Infection Control Fund’.

The latest trade union membership statistics show that the proportion of employees who were trade union members was highest in the Black or Black British ethnic group (27.2%) against a UK average of 23.5%.[5] Trade union membership density in health and social work is high compared to other sectors (39.7%), behind only public administration (44.2%) and education (48.7%). Enabling greater trade union access to workplaces and implementing sectoral collective bargaining would strengthen BME and migrant workers’ ability to negotiate for improved terms and conditions, raise concerns at work and to improve standards that benefit workers and those they are caring for.

4.We are interested in how ethnic minority workers can raise concerns at work. For example, about their treatment at work, or health and safety.

What specific processes are there for lower-paid ethnic minority workers to raise concerns?

What helps and what gets in the way of ethnic minority workers raising concerns? Are the processes accessible to and used by workers with different types of contracts? For example, zero-hour contracts and agency staff.

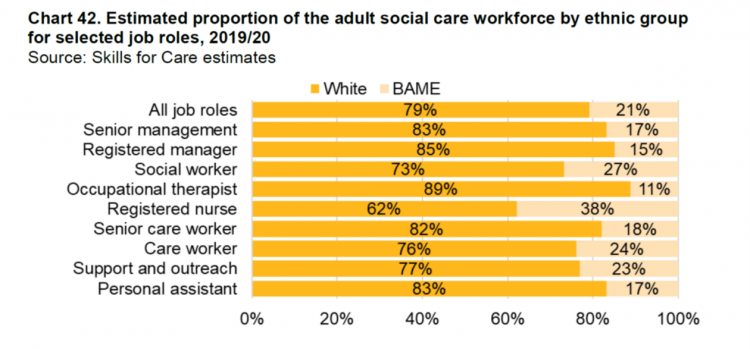

21% of the total health and social care workforce are identified as BME, compared to 14% of the population, and Black/African/Caribbean/Black British backgrounds (12%) accounted for over half of the BME adult social care workforce.[6] BME workers are overrepresented in front line care roles and underrepresented senior roles compared to their white colleagues. Discrimination faced by BME workers has been described as the single workforce issue of the pandemic by the NHS Confederation.[7]

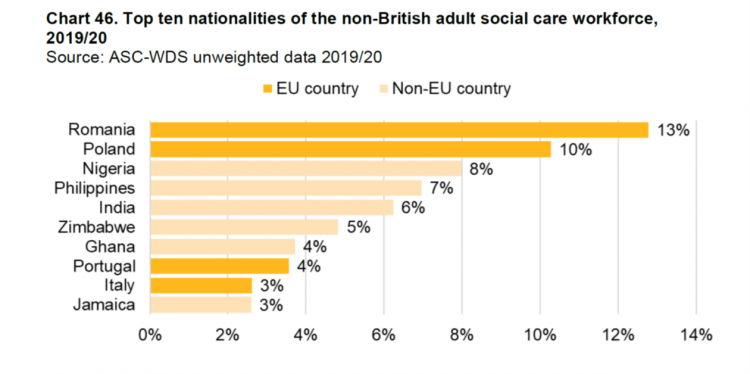

Six of the top 10 nationalities for non-British workers are African, Asian or Caribbean.[1]

The processes to raise concerns are the same for all staff, regardless of or ethnicity. They should all be able to raise issues with line managers or employers for example, or access formal procedures including grievance. However, access to routes of redress or how useful they are is disproportionate when taking contract type or ethnicity into the account. Given the concerns raised about how immigration status, over representation in low paying, insecure employment and the lack of support available to access rights, using these processes will be a very different experience for BME and migrant workers. The difference between the theory and the practice is evidence in recent TUC’s research, Dying on the job: risk and racism at work.[2]

BME workers experience systemic inequalities across the labour market that mean they are overrepresented in lower paid, insecure jobs. These inequalities are compounded by the discrimination BME people face within workplaces. TUC research carried out just before the outbreak of Covid-19 revealed that BME people’s experiences at work are blighted by discrimination: almost half of BME workers (45 per cent) have been given harder or more difficult tasks to do, over one third (36 per cent) had heard racist comments or jokes at work, around a quarter (24per cent) had been singled out for redundancy and one in seven (15 per cent) of those that had been harassed said they left their job because of the racist treatment they received. Yet very few had felt able to raise these issues.

In pre-pandemic polling of BME workers, we asked about the perpetrators of racism in their workplace. The most common response was ‘my direct line manager or someone else with direct authority’ (35 per cent). We also asked BME workers about the impacts that racism in the workplace had on them. Of those who experienced a racist incident, three in ten reported feeling less confident in work because of the most recent incident. Around a quarter (24 per cent) reported feeling embarrassed, and the same percentage said that the incident had a negative impact on their mental health. For 13 per cent, their physical health was impacted, and around one in ten people had to take time off work.

Some BME workers found it impossible to continue in their job following experiencing racism. Sixteen per cent of those who have experienced unfair treatment and racism at work said that the most recent experience led them to leaving their job, and a further 24 per cent said that they wanted to leave their job, but financial circumstances or other factors stopped them doing so. For others, their behaviour at work was affected. Fifteen per cent said that it made them avoid certain work situations, such as meetings, courses, locations or particular shifts, in order to avoid the perpetrator.

These show the challenges BME workers faced before the pandemic. After the onset of the pandemic, the TUC launched a call for evidence to properly understand the issues workers were facing and what their preferred solutions were. [3] Over 1,200 workers responded, a number of whom were worked in health and social care.

One in six of those responding to our call for evidence said that that during the pandemic they had been put at more risk because of their race or ethnicity. BME workers described being forced to undertake risky tasks, frequently on the frontline in health and social care roles. These tasks were often those that white colleagues had previously refused to do. A number of responses highlighted workers being asked to go on external visits when no one else would:

“I was made to do home visits when patients refused to come into hospital for the maternity care. Some of my white colleagues refused and I was given no choice.”

“I was sent to cover in another branch because they were low on staff due to some of them being high risk or abroad. Other colleagues didn't have to go because they were scared of putting themselves at risk; however, that didn't seem to be a reasonable reason not to ask me to.”

TUC analysis shows BME workers are more than twice as likely to be on agency contracts than white workers.[4] One in 24 BME workers are on zero hours contracts, compared to one in 42 white workers whilst one in 13 BME workers are in temporary work, compared to one in 19 white workers. In the social care sector, one in four workers are on zero hours contracts. This is as high as 42% in domiciliary care, where it is 56% for care workers.[5] In the NHS, around 10% of the workforce are insecurely employed.[6]

The stress and uncertainty created by the unpredictability of insecure work blights the lives of workers in ordinary times. But the Covid-19 pandemic has added a more deadly aspect to this lack of workplace power. Many of those filling key roles such as caring have found it harder to assert their rights for a safe workplace and access to appropriate PPE; to take time off for childcare responsibilities as schools have closed; and to shield if they or someone they live with is vulnerable. Their insecurity has increased their vulnerability, with all the risks to health and life that that brings.

Lack of workplace rights, and the knowledge that hours can be reduced, or temporary contracts not renewed, shapes the workplace experience of insecure workers, meaning they often have little choice but to comply with demands to expose themselves to higher levels of risk. As one worker explained when asked to do visits to the vulnerable and elderly during the pandemic.

"My other colleagues refused, I am still under a short-term contract and don't have similar rights as they did to refuse to do tasks."

Other BME workers were exposed to higher levels of risk within their usual workplaces. One nurse, for example, told us that she was always allocated to work with the patients with coronavirus, something that didn’t happen to white colleagues. When she asked if staff could be rotated so that no one person was always looking after coronavirus patients, her manager exploited her insecure status as an agency worker, threatening to inform her agency and stop booking her for work. She was then faced with a stark choice between being able to earn an income and continuing to be placed at increased risk which could threaten her life.

“I had to make a decision to either die on the job or move away quietly to save my dignity and health.”

The nurse felt that the experience typified the “racism and injustice” that she faced on a daily basis in her workplace, adding that in the past it had caused her to leave a permanent senior role.

The experiences of racism uncovered by TUC were echoed in a recent survey by UNISON.[7] % of BME workers in social care reporting experiencing racism and discrimination at work in the last year. This had a negative impact on the pay and progression opportunities for BME workers. Respondents identified the underrepresentation of BME workers in senior roles as one of the most obvious expressions of this.

“All the managers are white, the support workers are Black. It’s absurd during training or meetings because the divide is obvious. There’s not a single Black member in management.”

BME workers in the NHS face similar barriers to progression. In London, 43% of the NHS workforce are from a BME background. Yet only 14% of board level positions are held by BME staff.[8] Findings from the NHS ‘Race Equality Workforce Standard’ programme indicate this is a result of racism and prejudice against BME workers. Just 40.7% of BME staff believed that their organisation provides equal opportunities for career progression or promotion compared to 88.3% for white staff.[9]

5.We are interested in the health and safety of workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Have organisations carried out risk assessments for particular groups of workers?

How have they used the assessments for lower-paid ethnic minority workers during the pandemic?

Has this changed during the pandemic?

BME workers’ lived experience during the coronavirus crisis and the way that racism shapes the negative experiences that endanger their health, safety and wellbeing. We believe that this is a key factor in the disproportionate number of deaths of BME workers during the pandemic. TUC’s ‘Dying on the job’ report shows how the institutional racism and discriminatory treatment that BME workers experience has intensified during the crisis, putting their jobs and lives at risk.

The TUC believes that the most damaging of these factors are that:

- BME workers are overrepresented in the lowest paid occupations and are far more likely to be in precarious jobs than white workers. As a result, many BME workers may have felt that they had little choice but to work during the crisis (even where there was no access to PPE or other protections) because of the insecure nature of their jobs and lack of access to full employment rights.

- The experience of not having complaints of racism taken seriously or feeling that there may be negative consequences of raising complaints about racism has resulted in BME workers feeling that they have little power to affect their working environment. Many of the comments from BME workers in the report demonstrate that whilst they were aware of being disproportionately exposed to dangerous working situations during the coronavirus crisis, they didn’t feel that they could do anything about it.

- Racism in the workplace has led to BME workers being more likely to be assigned the worst tasks and most dangerous jobs in the workplace. A number of BME workers reported that they were deployed into frontline jobs while white colleagues were kept out of danger. Even when it was possible for them to be furloughed during the crisis BME workers complained that their employers insisted that they remain in the workplace. These experiences highlight the reality of BME workers not being valued as people or as workers.

- The inadequate provision of PPE has had a major impact on BME workers and their ability to protect themselves from Covid-19. A recurring theme in responses to our call for evidence was BME workers reporting feeling forced to work in dangerous situations without PPE where white colleagues were not or that the provision of PPE was discriminatory, even when it was available.

- The failure to conduct risk assessments to identify measures that could be put in place to reduce the risk of exposure to the virus was repeatedly highlighted by BME workers. This resulted in BME workers with underlying health conditions being unnecessarily exposed to the virus.

BME and migrant workers, particularly BME and migrant women, are more likely to work in public-facing roles in health and social care, putting them at greater risk of exposure to the coronavirus. This is due to the occupational segregation between BME and white workers - a result of systemic racism and discrimination in the recruitment and promotion processes in health and social care. BME staff are overrepresented in frontline job roles, such as care workers, cleaners and nurses, and underrepresented in managerial positions.[10]

Care workers faced the highest risk of mortality during the pandemics. Those in low paid, insecure roles – care home workers and domiciliary carers – accounted for the highest proportion (76%) of Covid-19 deaths within this group. Adjusting for age and sex, care workers had twice the death rate due to Covid-19 compared to the general population.[11]

Women and BME workers in care were overrepresented in Covid-19 related deaths. The care sector is occupationally segregated, with a high proportion of women, people identifying as Black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME), and migrant workers. BAME workers also appear to be “significantly overrepresented in the total number of COVID-19 related health worker deaths, with some reports showing that more than 60 per cent of health workers who died identified as BAME”.[12] Women, particularly BME and migrant women, working in care are the majority of those on the lowest pay.

Analysis of key worker roles shows:[13]

- There are 3 million people in high exposure jobs in the UK. 77% of them are women.

- Of these workers, 1,060,400 are earning ‘poverty wages.’ 98% (1,046,400) are women.

The median full-time weekly wage for a female care worker is £384.80.[14] This is £6.20 below even the Government’s poverty line. Even if they are receiving full-time earnings, carers working on the frontline are living £6.20 below the poverty line. This meant that many missed out on statutory sick pay as they did not meet the earning threshold. A cruel irony for those most at risk of exposure to Covid and a public health risk.

The required earning threshold for SSP also means that those who are in insecure forms of work in health and social care are also more likely to miss out because are likely to earn less. This is because their irregular hours may not result in them earning enough to meet the income threshold. Those in insecure jobs may force themselves in to work even if they are unwell – putting their clients’ or fellow workers’ health at risk.

BME workers in the NHS report that there are particular issues with their health and safety concerns being properly understood by NHS leaders.[15] BME workers also report finding it harder to raise concerns due to fear of negative repercussions and victimisation. UNISON’s survey also found that only 60% of respondents had felt able to raise concerns about infection control and safety with their managers or employers.[16]

“There's a general assumption that if you are Black, you don't know what you are doing. Until your colleagues are stuck, then they ask for your opinion. You are never the first person to be asked. You are always the last. So you start to not care and withdraw from contributing to ideas. You simply do as you are told even when it endangers your health. It's to protect your income.”

Overlooking contributions from BME workers and ignoring their concerns was common amongst responses to TUC’s call for evidence. Such behaviour undermines BME workers confidence and sense of safety at work. Leaders in health and social care must urgently find ways of listening to and learning from the experiences of BME colleagues. This must be done in a manner which does not invalidate what is being said: it must not be defensive, nor explain away what is being said. Organisations must ensure there are robust policies and procedures in place, negotiated with union representatives, that have the trust and confidence of all staff.

6.We are interested in what steps employers have taken to understand and protect the wellbeing of lower-paid ethnic minority workers, including those in insecure employment.

Have you seen any specific steps taken by employers during the pandemic?

Do you think there are additional steps that employers could take?

The impact of coronavirus on BME and migrant workers has shone a spotlight on multiple areas of systemic disadvantage and discrimination they face in the workplace. Responding to TUC’s call for evidence, BME workers highlighted several areas where they felt that action was needed to change their experiences of discrimination at work.[17]

In the short term, and in response to the pandemic, there are urgent steps that employers need to take. These include conducting appropriate risk assessments for BME workers. These risk assessments should, drawing on the latest public health advice, consider the particular risks for Black and ethnic minority workers, who have suffered disproportionate harm from the impact of Covid-19. Any assessments should be informed by thorough, sensitive and comprehensive conversations with BME staff that identify all relevant factors that may influence the level of risk they are exposed to, including any underlying health conditions and work arrangements. All workers must have access to appropriate PPE.

Other measures could have been considered by employers, such as deployment to alternative roles or enabling staff to work from home where risks to BME workers could not be reduced or removed. However, responses to our call for evidence highlighted a range of issues in relation to whether BME workers could work from home, how they were treated when they were there and whether or not they were furloughed.

A number of respondents reported still having to come into work while white colleagues, carrying out similar work, were allowed to work from home or were furloughed. One respondent, for example, told us how on the day that the government recommended everyone work from home if they can, all of his colleagues were sent to work from home. He was the only member of staff still expected to come into work. He is one of only two BME employees at his company. Similar experiences were described by a number or respondents. [18]

“I was asked to go out while everyone else was working from home. This was before I had PPE and before I had been given any by work.”

“Most people have been able to work from home. I have watched other colleagues being able to work from home. I feel I have been treated unfairly because till now I have not been told why I am not able to work from home when other non-black colleagues are working from home.”

“I'm the only mixed-race worker at work…One Asian lady with underlying health conditions. On the 23rd of March everyone was sent home whilst I was the only one asked to work in room where social distancing is not possible to work with families.”

BME workers working from home still reported experiencing unfair treatment from senior colleagues. Responses to our survey showed some BME workers who are working from home have been put under increased scrutiny and surveillance. Some workers faced not just extra scrutiny of their work, but extra scrutiny if they reported the need to work from home or called in sick. This mirrors a finding in our pre-coronavirus survey where over a third of BME workers (37 per cent) told us that they’d been subjected to excessive surveillance or scrutiny while at work. [19]

“While working from home I have felt more micromanaged than my white colleagues by senior management. I feel I am asked for more justification for what I have been working on. I also have not received the same level of sympathy and have been expected to do the same and quite often more than what I would at the office.”

“I had to fight to work from home, as I am asthmatic and take steroid inhaler. I had to go to occupational health for them to say yes, I need to work from home. While I was working from home, my work tripled, I became stressed as I was working well into the night to complete the work. I did report it. There was a] lack of support for us working at home. Like we are second class. I felt alone, and not supported.”

“I suffered from Covid symptoms and it was made out to look as if I were being dishonest. Two other colleagues who are white were given special paid leave, where I was told to come back to work or I would not be paid.”

Others experienced the opposite: being told to work from home but left adrift and excluded once there. [20]

“I have just been left at home without any regular contact with managers, no access to work equipment to do my job, no internet access or dongle, and I can't even get a referral back to occupational health to raise my request for … work equipment.”

A recurring theme in responses to the call for evidence was feeling unsupported. One respondent spoke about the upsetting contrast between watching press conferences where the prime minister would speak about the higher death rate for BME people and then going to meetings in which colleagues would make flippant jokes about coronavirus. One journalist spoke about how just being checked in on would have been appreciated:

“Although I don’t feel like I have been singled out and given difficult work, as the discussion of race has started only one colleague has checked up on me despite hundreds of racist comments from readers.”

7.We are interested to learn more about the progression of lower-paid ethnic minority workers within in the workforce.

Is the progression of ethnic minority workers monitored?

Are ethnic minority workers able to progress from lower-paid, insecure employment, into more secure employment?

How would someone progress from a zero-hour contract to part-time employment, or progress to be being paid more?

Are there any issues that need to be addressed for ethnic minority workers?

BME workers are overrepresented in the health and social care workforce compared to their representation in the general population. Yet, they are underrepresented in middle and senior management positions.

- In the NHS, 6.8% of very senior managers are from a BME background, despite 20% of the workforce being from a BME background [21]

- In social care, 7% of middle and senior managers are from a BME background while a quarter of the overall workforce are BME[22]

To address the issue of progression in work, it is important to understand the realities of the labour market already for BME workers. BME workers face lower employment rates; and unemployment rates are twice as high for BME workers than white workers.[23] There are significant pay gaps for BME workers at all levels of qualifications, and BME workers are more likely to be in insecure work compared to white workers.

These disparities are a result of discrimination BME workers face when applying for jobs and once they are in employment. A 2019 report by the Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College found that, despite having the same skills, qualifications and work experience, job applicants from an ethnic minority backgrounds had to send 60 per cent more applications than white British candidates before they received a positive response.[24]

The NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) has for many years demonstrated that every organisation in the NHS, national and local, offered much poorer experiences to BME employees relative to their white colleagues. Its evidence includes analysis of promotion opportunities, with white applicants being 1.61 times more likely to be appointed from shortlisting compared to BME applicants; this is worse than in 2019 (1.46).[25]

Discrimination continues once BME people are in work. BME workers in the NHS were more likely to report experiencing discrimination and unfair treatment, either from a manager or colleague, compared to white colleagues, 14.5% and 6% respectively.[26]

In 2019, 71.2% of BME staff believed that their trust provides equal opportunities for career progression or promotion, compared to 86.9% of white colleagues. In Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCG’s), this falls for BME staff to 40.7% but increases for white staff to 88.3%. [27]Our pre-coronavirus survey found that 45 per cent of BME workers have been unfairly criticised while at work, and 35 per cent have been given an unfair performance assessment.[28]

Undue criticism has continued during the pandemic. One respondent to our call for evidence talked about how, despite all the extra effort during the lockdown, praise has not been forthcoming:

“There is also hardly ever any praise for the fact work has not slipped despite lockdown. I was ready for work immediately the next morning after lockdown yet my white colleagues took two weeks off to adjust and that was seen as fine. However when I did get ill despite my out of office people continued to pile on work for me via emails and someone made a comment about me enjoying the sun in the garden when I was so weak I could barely eat or go to the toilet. It was clear they felt I am faking my illness when I had symptoms of Covid-19.”

Another respondent outlined the extra effort BME workers must put in just to avoid the criticism of white colleagues:

“People of colour should feel valued and not just pushed to work … the majority of BME are really hard workers and feel that if we aren't giving 150% others call you … lazy or not a team player. The expectation for people of colour is so high and what white people get away with BME workers would never get away with.”

BME workers aren’t just singled out for undue criticism. Almost a quarter of BME workers (24 per cent) in our pre-coronavirus survey reported being singled out for redundancy at one point during their working lives. Again, this was reflected among the responses to our online survey. For BME women, racism can intersect with gender-based discrimination, increasing their risk of unfair treatment.

“I have been fired during the pandemic whilst my white male colleague who is the same rank as me has not. I am a brown woman.”

Tackling low pay and insecure employment would help workers progression and overcome the barriers to security that is highlighted in the responses above. Seven in ten workers in social care are paid less than £10 per hour and the already high numbers highlighted on zero hours contracts, show that raising pay and banning zero hours contracts would make a big difference to a significant number of workers.[1]

10.We’re interested in whether or not organisations consider the terms and conditions of workers in contracted services.

Have you seen employers using their equality duties to ensure fair treatment and inform their decision-making? For example, by gathering and analysing data about the employment patterns and experiences of ethnic minority workers.

How could employers do this better?

Ethnic monitoring and regular reporting are essential if businesses and other employers are to identify and address patterns of inequality in the workplace. Organisations need to collect baseline data, update this information regularly so that the information can be seen in the context of wider trends, and measure results against clear, timebound objectives.

Proposals are being considered to introduce mandatory ethnicity pay gap reporting, which the TUC strongly support. Employers in health and social care do not need to wait for the government to introduce mandatory ethnicity pay- gap reporting and action plans. We recognise that many employers do not currently have detailed systems for ethnic monitoring. However, we urge these employers to act swiftly to introduce workforce ethnic monitoring that allows them to develop an evidence-based plan addressing inequality experienced by BME staff.

Without up-to-date ethnic monitoring data on areas such as retention, recruitment and promotion, training and development opportunities and performance management, employers will find it difficult to develop a clear picture of their workplace and identify any areas where BME staff are underrepresented or potentially disadvantaged.

11.Is any specific action required to address the issues that you have raised that affect lower-paid ethnic minority workers? (please answer below)

Who needs to take action? For example, is it employers, or is a change in legislation required? (please answer below)

The TUC believes that it is essential for the voices of BME workers to be listened to and that their experience inform the decisions about what action needs to be taken to tackle racism within the workplace. If these experiences are ignored then, as in the past, the policies and practices that are implemented will not result in the transformative change that we need.

Immediate legislation changes that would significantly improve the situation faced by BME low paid workers in health and social care during the pandemic, include:

i) Abolish the lower earnings limit (and any earnings threshold) for receiving Statutory Sick Pay, extending coverage to almost two million workers

ii) Increase the weekly level of sick pay from £94.25 to the equivalent of a week’s pay at the Real Living Wage

iii) Introduce a ban on zero-hours contracts, a decent floor of rights for all workers and the return of protection against unfair dismissal to millions of working people

iv) End the public sector pay freeze, giving all key workers a significant and meaningful pay rise

v) Ensure all care workers are paid a living wage, raising the National Living Wage to £10 per hour

In the longer-term, there are steps the government can take to end structural and institutional racism within health and social care workplaces, and across the labour market:

- create and publish a cross-departmental action plan, with clear targets and a timetable for delivery, setting out the steps that it will take to tackle the entrenched disadvantage and discrimination faced by BME people; in order to ensure appropriate transparency and scrutiny of delivery against these targets regular updates should be published and reported to parliament

- strengthen the role of the Race Disparity Unit to properly equip it to support delivery of the action plan

- introduce mandatory ethnicity pay-gap reporting alongside a requirement for employers to publish action plans covering recruitment, retention, promotion, pay and grading, access to training, performance management and discipline and grievance procedures relating to BME staff and applicants

- demonstrate transparency in how it has complied with its public sector equality duty through publishing all equality impact assessments related to its response to the coronavirus pandemic.

- Allocate EHRC additional, ringfenced resources so that they can effectively use their unique powers as equality regulator to identify and tackle breaches of the Equality Act. These increases would help identify and tackle the issues facing BME workers in relation to the impact of Covid-19 but should be ongoing. These resources should be commensurate to the challenges faced, particularly in light of the decreased funding that CRE had in 2006 for race issues (circa £90m) compared to the EHRC present funding of £17.1million for its entire work across protected characteristics.

Employers should:

- undertake proper job-related risk assessments to ensure that BME workers are not disproportionately exposed to coronavirus and take action to reduce the risks, through the provision of PPE and other appropriate measures where exposure cannot be avoided

- establish an ethnic monitoring system that as a minimum covers recruitment, promotion, access to training, performance management and disciplinary and dismissal, and then evaluate and publish this monitoring data alongside an action plan to tackle any areas of disproportionate under or overrepresentation identified.

- undertake a workplace race equality audit to identify institutional racism and structural inequality

- work with trade unions and workforce representatives to establish targets and develop positive action measures to address racial inequalities in the workforce.

In addition, urgent action is needed to fix our social care services:[2]

- A new long-term funding settlement, as a matter of urgency, that offsets the damage done by cuts to essential services under austerity, meets rising demand and gives social care workers the pay rise they deserve. This must immediately relieve local authorities of cost pressures and tackle the high turnover rates in the social care workforce, ultimately expanding eligibility thresholds, lessening the load on unpaid carers and reducing costs for individuals and their families.

- A national care body, representing the government, trade unions, employers and commissioners, mirroring the Social Partnership Forum in the NHS. This sectoral body should develop and negotiate a workforce strategy as a priority, and be used to facilitate negotiation, organise sectoral interests and coordinate rapid responses to on the ground information.

- Fair pay and decent work for the social care workforce, including a £10 an hour minimum wage, an end to zero-hour contracts, better sick pay and a real valuing of care skills. A national skills and accreditation framework linked to a transparent pay and grading structure should be established, and negotiated by the national care body, ensuring genuine career progression, proper recognition and fair reward for all.

- The introduction of sectoral collective bargaining, as the most effective way to negotiate standards of pay, pensions, health and safety and to ensure a fairer a share of productivity gains, better pay, terms and conditions and working practices and lower staff turnover.

- A limit on private sector involvement in social care, through the introduction of legislative and regulatory measures to end financial extraction in the care home sector as a first step. Ending the for-profit model in a public service as essential as social care will ensure greater stability for commissioners, workers and the cared for, greater value for money to the public purse, and embed accountability, transparency and standards.

Organisation’s contact details

If you have any further questions, need more information, and to send us a copy of the final report, please contact:

Jay McKenna – jmckenna@tuc.org.uk or 07788414578

Submitted on behalf of the Trades Union Congress (TUC), Congress House, Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3LS

[1] TUC (2018) Taylor Review: Enforcement of employment rights

[2] TUC (2015) Outsourcing public services is damaging for staff and service users, says TUC | TUC

[3] Skills for Care (2020) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce 2020 available at https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-2020.pdf

[4] Skills for Care (2020) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce 2020 available at https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-2020.pdf

[5] Ibid

[6] TUC (2019) A stronger voice for workersA stronger voice for workers

[7] TUC (2017) Working in the UK - a guide to your rights | TUC

[8] NHS (2020) NHS Workforce Statistics available at NHS workforce statistics - NHS Digital

[9] Skills for Care (2020) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce 2020 available at https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-2020.pdfl

[10] Skills for Care (2020) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce 2020 available at https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-2020.pdf

[11] Ibid

[12] TUC (2020) Dying on the job: Risk and racism at work available at Dying on the job - Racism and risk at work | TUC

[13] LAWRS (2019) The unheard workforce available at Unheard_Workforce_research_2019.pdf (lawrs.org.uk)

[14] OECD (2018) Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work, The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en

[15] Trade Union membership stats (2020) BEIS https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/trade-union-statistics-2019

[16] NHS (2021) Workforce-Race-Equality-Standard-2020-report.pdf (england.nhs.uk); Skills for Care (2020) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce 2020 available at https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-2020.pdf

[17] NHS Confederation (2020) REPORT_NHS-Reset_COVID-19-and-the-health-and-care-workforce.pdf (nhsconfed.org)

[18] Skills for Care (2020) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce 2020 available at https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-2020.pdf

[19] ibid

[20] TUC (2020) Dying on the job: Risk and racism at work available at Dying on the job - Racism and risk at work | TUC

[21] TUC (2020) Dying on the job: Risk and racism at work available at Dying on the job - Racism and risk at work | TUC

[22] TUC (2019) BME workers trapped in insecure work available at BME workers far more likely to be trapped in insecure work, TUC analysis reveals | TUC

[23] Skills for Care (2020) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce 2020 available at https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/adult-social-care-workforce-data/Workforce-intelligence/documents/State-of-the-adult-social-care-sector/The-state-of-the-adult-social-care-sector-and-workforce-2020.pdf

[24] NHS (2018) NHS Workforce Bank Staff available at NHS Workforce Statistics - Bank Staff - data.gov.uk

[25] Unison survey of black members in social care – EHRC Inquiry submission

[26] Kings Fund (2018) Closing the gap on BME representation in NHS leadership: not rocket science | The King's Fund

[27] NHS (2021) Race Equality Workforce Standard 2020 available at Workforce-Race-Equality-Standard-2020-report.pdf (england.nhs.uk)

[28] TUC (2020) Dying on the job: Risk and racism at work available at Dying on the job - Racism and risk at work | TUC

[29] The Health Foundation (2020)

[30] Amnesty International (2020)

[31] Autonomy (2020) Jobs at risk index available at COVID-19: Jobs At Risk Index (JARI). Which occupations are most at risk? - Autonomy

[32] Women’s Budget Group (2020) When crises collide: Women and Covid-19

[33] NHS Confederation (2020) REPORT_NHS-Reset_COVID-19-and-the-health-and-care-workforce.pdf (nhsconfed.org)

[34] Unison survey of black members in social care – EHRC submission 2021

[35] TUC (2020) Dying on the job: Risk and racism at work available at Dying on the job - Racism and risk at work | TUC

[36] Ibid

[37] TUC (2020) Dying on the job: Risk and racism at work available at Dying on the job - Racism and risk at work | TUC

[38] Ibid

[39] NHS (2021) Race Equality Workforce Standard 2020 available at Workforce-Race-Equality-Standard-2020-report.pdf (england.nhs.uk)

[40] NHS (2020) Digital stats on social care workforce available at Home - NHS Digital

[41] TUC (2020) Dying on the job

[42] Are Employers in Britain Discriminating Against Ethnic Minorities? Centre for Social Investigation at Nuffield College (2019). Available at: http://csi.nuff.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Areemployers-in-Britain-discriminating-against-ethnic-minorities_final.pdf

[43] NHS (2021) Race Equality Workforce Standard 2020 available at Workforce-Race-Equality-Standard-2020-report.pdf (england.nhs.uk)

[44] Ibid

[45] Ibid

[46] TUC (2020) Dying on the job

[47] TUC (2020) Fixing social care | TUC

[48] TUC (2020) Fixing social care | TUC

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox