NHS workforce crisis - a decade in the making

The workforce crisis currently facing the NHS has been a decade in the making, driven by deep funding cuts and government-imposed pay restraint.

The TUC is calling on the government to take immediate action to end the NHS workforce crisis, including:

- Delaying mandatory vaccination as a condition of deployment in the NHS with immediate effect.

- Putting in place an urgent retention package, with an early and decent pay rise at its heart. This must reverse a decade of lost wages and ensure pay keeps pace with the rising cost of living. This package should be reflected in the government’s submission to the NHS pay review body.

- Taking all necessary steps to minimise delays to the pay review process to ensure staff receive their 2022 pay award as close to 1 April 2022 as possible.

- Ensuring all NHS staff have priority access to lateral flow and PCR tests, high quality PPE, and workplaces that are properly ventilated to minimise transmission and infection.

To address the longer-term issues facing the NHS, ministers must:

- Significantly increase investment in the NHS that reverses a decade of cuts and enables employers to recruit for and maintain safe staffing levels.

- Implement a fully costed and funded long term workforce plan that addresses vacancy issues, supports retention and that improves services for patients.

Introduction

The TUC brings together more than 5.5 million working people who belong to our 48 member unions. We support trade unions to grow and thrive, and we stand up for everyone who works for a living. Every day, we campaign for more and better jobs, and a more equal, more prosperous country.

This briefing sets out some of the issues behind the NHS’s recruitment and retention crisis and sets out the TUC’s key recommendations to resolve them. It contains first-hand testimonials from current NHS workers and trade union members, put in perspective with statistical evidence collected over the last 10 years.

The recruitment and retention crisis existed long before the pandemic - driven by a decade of funding cuts and pay restraint. Unfilled vacancies put huge strain on staff, leading to burnout, sickness absence and turnover. The cumulative impact of coping with these shortages whilst working on the frontline of the pandemic has led many key workers in the NHS to breaking point and pushed the backlog in elective treatment to record-breaking levels.

While the government have indicated tackling the backlog is a priority, investing revenue raised from a new increase in national insurance contributions, the health system’s ability to do this will be undermined without additional investment and action to tackle the recruitment and retention crisis facing the NHS and the crisis in social care.

Government should work with NHS staff and their unions to fix the long-term issues behind the current crisis. Doing so will help us clear the backlog and ensure we have a robust and resilient NHS ready to meet the challenge of coronavirus and any future pandemics.

Tackling the immediate crisis

In early January 2022, covid cases in hospitals reached the highest levels since February 2021. Simultaneously, NHS staff sickness and absence reached dangerously high levels, driven by a toxic combination of burnout, stress and the Omicron outbreak.

NHS trusts are battling to maintain safe staffing levels. In January 2022, NHS England data shows more than 80,000 staff were absent each day, an increase of 13 per cent from the previous week. Just under half of those absences were covid-related, up 59% on the previous week (24,632) and more than three times the number at the start of December (12,508).

However, NHS Trusts have less than week to begin implementing the government’s new mandatory vaccination as a condition of deployment policy. The 3 February 2022 is the last date for workers to get their first dose to be fully vaccinated in time for when the regulations take force from 1 April 2022. Those who do not meet the February deadline, will be redeployed away from the frontline or find themselves out of a job altogether.

Implementing this policy in the midst of a staffing crisis will create a bureaucratic nightmare for NHS Trusts and make it impossible to maintain safe staffing levels in the coming weeks, let alone maintain capacity to tackle the backlog. The NHS cannot afford to lose experienced, valued staff at a time like this.

Recommendation

- Government delay the implementation of the mandatory vaccination policy, ensuring NHS Trusts and their staff can get on with the vital work of responding to the pandemic and focusing on patient care. The TUC strongly urges everyone who isn’t medically exempt to get vaccinated and boosted, and for ministers to make that as easy for whole NHS staff team.

- The government should arrange priority access to lateral flow and PCR tests for all key workers in health and other vital public services. This should reach more than the current proposal for just 100,000 ‘critical workers’ and must include outsourced NHS workers such as porters and cleaners.

- In addition, high-quality personal protective equipment (PPE), including respirator masks (FFP3 model), should be made available to health and care workers, not just those who work directly with Covid patients. These are effective in limiting aerosol transmission, and reducing the risk of infection and transmission.

Pay trends in the public sector since 2010

“My wage definitely doesn't stretch as far now. When I go to the shops I have a choice: do I pay the bills or do I buy food? I have to think about whether I can keep my heating on for longer, which is scary.”

Enrika 1 , Domestic services worker, union representative

TUC analysis shows that wages of NHS staff are still below 2010 levels after taking inflation into account, even after factoring in the 2021 pay award for NHS staff.

Comparing 2010 wages in real terms today (if they had kept up with the cost of living) with 2021 wages for individual occupations at the top of agenda for change pay scale, TUC analysis found that:

- Porters (higher level) pay is down by £920 (-4.4%)

- Medical secretaries pay is down by £1,330 (-5.8%)

- Maternity care assistants and nursery nurses pay is down by £2,231 (-8.2%)

- Nurses and community nurses pay is down by up to £2,715 (-7.9%)

- Midwifes, radiographer specialists and paramedics pay is down by £3,500 (-8.2%)

- Occupational therapist (advanced) pay is down by £4,110 (-8.2%)

Without action to restore the value of NHS workers’ pay, we risk a worsening of the recruitment and retention crisis. As Enrika told us:

“It's wrong. I have a son who works in retail and he comes out with more money than me... I put my life at risk going to work. I often think to myself, will I be in this job in a year's time? And I'm not quite sure.”

Recommendations

- Government should take immediate action to put in place an urgent Retention Package, with a decent pay rise at its heart. The 2022 pay uplift needs to be set at a level which will retain existing staff within the NHS and recognises and rewards the skills and value of health workers. The increase must:

- Deliver an inflation-busting increase so that NHS staff can cope with rising and rapidly fluctuating costs which may change significantly over the pay year

- Absorb the impact of increases to pension contributions

- Benchmark the bottom of the structure against the Real Living Wage

- Government should take all necessary steps to minimise delay to the pay review process to ensure staff receive their 2022 pay award as close to 1 April 2022 as possible.

Recruitment and retention trends since 2010

“In terms of morale, staff are exhausted. They're really tired. We're working with numbers that are really, really short… it's across the board.”

Alison 2 , senior midwife coordinator, Union member

The NHS faced a recruitment and retention crisis prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. In March 2010, the total vacancies among NHS medical and dental staff (hospital doctors and dentists excluding training grades) was 4.4 per cent. 3 By June 2019, this had risen to close one in ten jobs vacant (9.2 per cent). 4 In September 2021, NHS England was operating short of almost 100,000 staff due to unfilled vacancies.5

Nursing and midwifery continue to experience some of the worst recruitment and retention issues. The most recent figures show that there are nearly 40,000 vacancies for registered nurses in England. This represents a vacancy rate of 10.5 per cent.6 These are two of the top five occupations that have experienced the sharpest fall in pay since 2010.

In 2020, the Government committed to recruiting an additional 50,000 nurses in the NHS in England by the end of this Parliament. However, there is no published strategy for the approach or any specified funding. Without concrete and targeted action from the government, employers cannot effectively plan for and begin to tackle the mounting NHS backlog.

Staff shortages in primary care

“The NHS has become more strained in every capacity. The staffing levels are much worse than they were when I first started [12 years ago]. People are leaving. They have had enough.”

Philipa 7 , Business manager, NHS hospital Foundation Trust, Union member.

Moving care from hospitals to primary and community health services has long been a policy goal, reflected in the NHS Long Term plan. But a recent report from the BMA shows that as of September 2021 there is an equivalent of 1,756 fewer fully qualified full-time GPs compared to 2015.8

BMA analysis reveals that there are now just 0.45 fully qualified GPs per 1,000 patients in England – down from 0.52 in 2015.9 This means increasing numbers of patients to take care of for the GPs that remain: the average number of patients each GP is responsible for has increased by around 300 – or 16 per cent - since 2015.10

The Conservatives’ general election manifesto in 2019 promised to deliver 50 million more GP surgery appointments a year. Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, Sajid Javid recently admitted that the figure was unlikely to be met. 11

Instead of reliving pressure on hospital and emergency care services, the failure to recruit and retain GPs is worsening the strain.

Recommendation

- The government needs to act now to stabilise and grow the NHS workforce, including the number of doctors, nurses and midwives. Alongside introducing an urgent retention package, the government need to implement a fully-funded, long-term workforce strategy designed with workers and their representatives.

Fixing social care

“Shortfalls in the social care system are also adding to the problem. With no other support available, staff attending vulnerable elderly patients often have no option but to take them to hospital. They are then left queueing outside hospitals, preventing crews from getting back on the road to deal with the next emergency.”

Sara Gorton, Head of Health at UNISON the union

Bed occupancy in hospitals remains high. Only 42 per cent of patients who no longer need to reside in hospital are being discharged.12 That is equivalent to almost 10,000 patients a day, according to NHS England.

On average, nine in ten (90 per cent) long stay patients (in hospital for three weeks or more) are not being discharged back into the community despite being ready to. This is due to a chronic lack of capacity in the social care sector.

Capacity issues in social care are driven by the same issues affecting the NHS – a decade of chronic underfunding and a staffing crisis.

The workforce crisis in care is driven by a toxic mix of low pay, insecure employment and poor working conditions. TUC analysis shows seven out of ten care workers earn less than £10 per hour and over a quarter of the workforce are employed on zero-hours contracts.13

Social care has a vacancy rate of 9.4 per cent, equivalent to 105,000 vacancies across the sector.14 This has stayed consistently high over the last decade. However, in England, the turnover rate rose from 23.1 per cent in 2012-1315 to 34.4 per cent in 2020-21.16 This equates to 440,000 leavers in the past twelve months, at a time when demand is surging for social care. Without action, the situation will continue to worsen and the pressure on hospitals will increase.

Recommendations

-

Government should establish a national care body, with representatives from trade unions, employers and government, that would enable all parties to negotiate and agree on a range of issues that would drive up standards in the sector.

-

Government should give all care workers an immediate pay rise to £10 per hour, paid for by equalising capital gains tax (CTG) with income tax, generating an additional £17 billion in revenue.17

Wait times

“We're taking the brunt of other failings in the NHS; the lack of hospital beds, lack of hospitals, and GP appointments. If everything else was fine we'd manage ok. But obviously it's a knock-on effect.

Steve18 , Clinical care manager, Ambulance Service, Union member

Accident & Emergency departments are at breaking point, operating at full capacity, with patients forced to wait in ambulances for up to 11 hours outside hospitals.

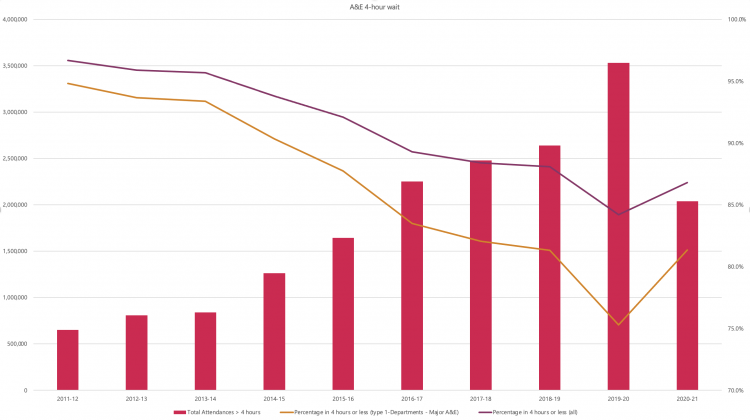

In 2011/12, 94.8 per cent of patients were admitted, transferred or discharged within four hours of arriving at a major A&E department.19 This number has consistently dropped over the last decade. In 2020/21 only 81.3 per cent of patients waited less than 4 hours.20

Once admitted to A&E, NHS staff report patients have been left on trolleys for hours while staff waiting with them are unable to get to other jobs:

“Ten years ago, paramedics would do between 12-14 jobs in one shift, but now many paramedics have to stand in corridors with patients for hours. I've known [ambulance service] staff to wait in a corridor for up to four hours.”

Steve 21 , Clinical care manager, Ambulance Service, Union member

- 1 Names have been anonymised

- 2 All names have been anonymised

- 3 NHS digital, NHS Vacancies Survey - England, 31 March 2010

- 4 NHS digital, NHS Vacancy Statistics England April 2015 – September 2021 Experimental Statistics

- 5 ibid

- 6 ibid

- 7 All names have been anonymised

- 8 BMA (2022) Pressures in general practice (bma.org.uk)

- 9 “

- 10 Ibid

- 11 The Guardian (2021) No 10 set to break promise of 6,000 more GPs in England, Sajid Javid says (theguardian.com)

- 12 NHS England (2022) NHS weekly winter operational update

- 13 TUC (2021) A new deal for Social Care: A new deal for the workforce | TUC

- 14 Skills for Care (2022) Vacancy information - monthly tracking (skillsforcare.org.uk)

- 15 Skills for Care (2017) State of the adult social care sector and workforce 2017 (skillsforcare.org.uk)

- 16 Skills for Care (2021) The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England (skillsforcare.org.uk)

- 17 TUC (2021) A new deal for Social Care: A new deal for the workforce | TUC

- 18 Names have been anonymised

- 19 NHS England A&E Attendances and Emergency Admissions (england.nhs.uk)

- 20 Ibid

- 21 Names have been anonymised

The King’s Fund notes that resources to treat A&E patients have not kept pace with rising demand. For example, while the NHS has been admitting more patients through A&E the number of general and acute overnight beds available in Q4 2018/19 was 4 per cent less than in Q4 2011/12, and the percentage of them that were occupied has risen from 89 per cent to 92 per cent.22

Latest figures from the NHS show a record waiting list of 5.99 million people waiting for elective treatment. More than 2 million have been waiting for more than 18 weeks.23 This is the highest level since records began in 2007.

Backlogs were already growing before the pandemic. In February 2020, there were 4.42 million people waiting for elective care.24 This is almost twice the number of people waiting for elective care in 2010 (2.34 million people in February 201025 ). Infection control measures and the diversion of resources towards Covid have only exacerbated it. A recent National Audit Office (NAO) report states that as services resume and patients who did not seek care during the pandemic return to the NHS, the elective care waiting list could reach 12 million by March 2025.26

The Health Foundation estimates that it will cost up to £16.8bn over the remainder of this parliament (up to 2024/25) to enable the NHS to clear the backlog of people waiting for routine elective care, return to 18 weeks, and treat millions of ‘missing’ patients who were expected to receive care during the pandemic but did not.27

Health and wellbeing of the NHS workforce since 2010

“I'm coming to the end of my career and I'm quite resilient but working in the NHS is relentless. We see junior people leaving because they can't cope with the pressure that they're under. I’ve spent my whole career in the NHS, but now I look around, and I don't think it's a job for a whole career anymore.”

Alison 28 , senior midwife coordinator, Union member

To protect our NHS, we need to protect its workforce. Low pay, excessive workloads and a decade of deep funding cuts have taken their toll on the health and wellbeing of NHS staff.

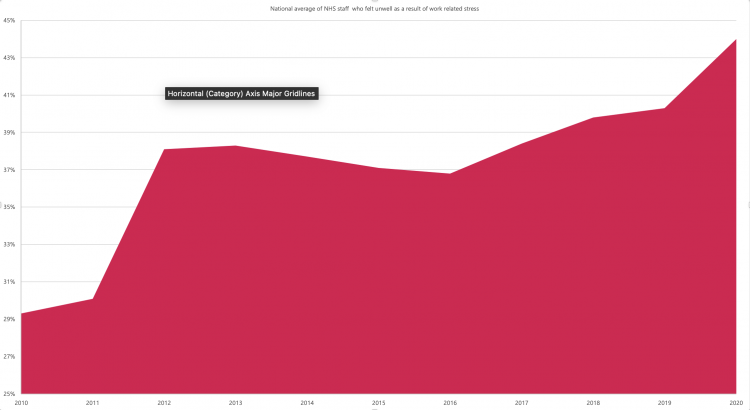

In 2019, the NHS staff survey found high levels of work-related stress amongst the workforce, with 44 per cent of registered nurses and 40 per cent of nurses and health care assistants reporting feeling unwell as a result of work-related stress in the previous 12 months.29 In 2020, after the start of the pandemic, more than four in 10 (44 per cent) NHS staff reported feeling unwell as a result of work-related stress.30

This number has increased by more than 50% since 2010, when just under three in 10 (29 per cent) staff were reporting feeling unwell due to work-related stress.31

While the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated stress levels of staff, with a rise of 10 per cent between 2019 and 2020, the most significant jump in reported levels of staff occurred between 2011 and 2012 when staff stress level increased by 26%.

- 22 The King’s Fund (2019) Accident and emergency waiting times (kingsfund.org.uk)

- 23 NHS England Consultant-led Referral to Treatment Waiting Times Data 2021-22 (england.nhs.uk)

- 24 Ibid

- 25 Ibid

- 26 NAO (2021) NHS backlogs and waiting times in England (nao.org.uk)

- 27 The Health Foundation (2021) Health and social care funding to 2024/25 (health.org.uk)

- 28 Names have been anonymised

- 29 NHS England (2021) Working together to improve NHS staff experiences | NHS Staff Survey (nhsstaffsurveys.com)

- 30 Ibid

- 31 NHS England NHS staff survey 2010 (nhsstaffsurveys.com)

In the NHS, anxiety, stress, depression and other psychiatric illnesses are consistently the most reported reasons for sickness absence, exceeding other reasons for absence. They accounted for more than a quarter (27.8 per cent) of staff absences in August 2021.32 The highest levels of sickness absence due to stress are being seen for midwives, ambulance staff and managers.

By reversing a decade of underfunding in the NHS, increasing investment to enable employers to recruit for and maintain safe staffing levels, government can bring down levels of work-related stress and resulting absence.

Excessive workloads

“There’s more work to do and less resources to do it with. Working in the NHS takes over your life. It is not sustainable. Everybody is at breaking point.”

Philipa 33 , Business manager, NHS hospital Foundation Trust, Union member.

The latest NHS staff survey shows that in 2020, nearly four in 10 (37.9 per cent) of NHS staff believe there are not enough people in their organisations to enable them to do their job properly. 34

Hardworking and overstretched NHS staff are working tirelessly to help patients. But there are simply not enough of them to keep up with demand. Unfilled vacancies put additional strain on remaining staff trying to fill the gaps.

The pandemic has worsened this situation. NHS England data shows 39,142 NHS staff at hospital trusts in England were absent for Covid-19 reasons on January 2, up 59% on the previous week (24,632) and more than three times the number at the start of December (12,508).

- 32 NHS Digital NHS Sickness Absence Rates, August 2021, Provisional Statistics (digital.nhs.uk)

- 33 Names have been anonymised

- 34 NHS England (2021) Working together to improve NHS staff experiences | NHS Staff Survey (nhsstaffsurveys.com)

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox