Jobs and recovery monitor - wage squeeze continues

-

New TUC polling shows 2/3 of workers expecting pay to fall behind the cost of living this year

- ONS business polling shows only 8% of firms regard wages as higher than normal, 6% think they are lower than normal, and 52% reckon wages have not been affected by the pandemic

- Average weekly earnings in the private sector grew by 4.1% in November down from 4.7% in October

- Public sector pay growth in November 2021 was only 2.6%

- Across most industries pay growth is slowing; there are no industries where pay is accelerating in a significant way

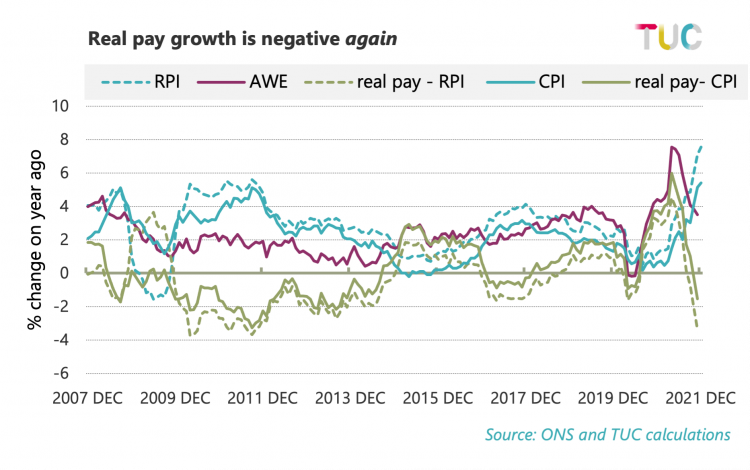

- Inflation is at 30-year highs, with in December CPI at 5.4% and RPI at 7.5%

- Headline real pay growth is now negative, falling by 1.5% on the year (on CPI, the worse for eight years) and 3.4% (on RPI, the worse for ten years)

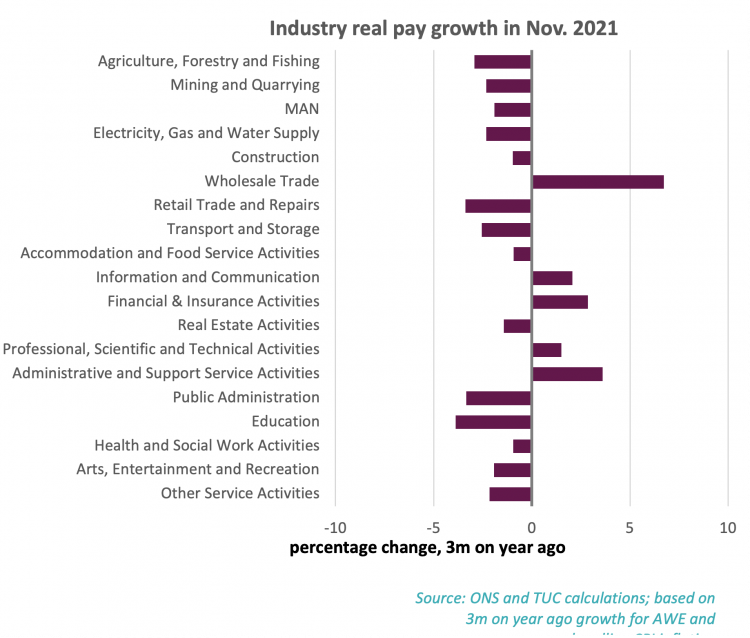

- For three quarters of industries (14 of 19) real pay is falling

- The largest real pay declines are in the public sector: education (-3.9%) and public administration (-3.3%), alongside retail trade (-3.4%)

The ‘cost-of-living crisis’ currently hitting workers is not just one of rising prices. Compounding the pressures from high inflation is slowing pay growth. Headline pay growth – before prices are taken into account- slowed to 3.8% in November from 4.2% in October. The sum of the parts is negative real pay, and so a return to the unacceptable but dominant outcome of the past decade,

Recent commentary about shortages and bottlenecks being good for workers is already proving wishful thinking. More specifically the latest Bank of England assessment does not match our own findings.1 But there are several sides to the story. For some private sector industries on the front line of the pandemic, increased demand for workers apparent in the employment figures is leading to higher pay growth. And at company level, unions in a number of industries have worked to secure inflation-busting pay rises, and forcing firms to begin to address structural defects that have long hampered dynamism and recruitment.2

But across the majority of the private sector workers face falling real pay. And in spite of its pivotal role in the pandemic economy public sector workers are seeing the biggest reductions to pay growth. And survey evidence suggests that neither workers or firms expect the pay squeeze to end soon.

Measures to tackle the health crisis have meant a ‘pandemic economy’ has rapidly emerged, with some industries and jobs seeing rapid growth, but the winners are still greatly outnumbered by the losers. The Government immediately needs to act to support all workers:

- Higher pay is the best solution to the cost of living crisis. Workers have endured the worst pay crisis for at least two centuries, higher pay will support spending and so strengthen the economy. Low pay will cut spending and further weaken the economy

- The pandemic has taught us the importance and power of government action to protect the economy and workers. Policymakers need to keep monetary and fiscal policy on an expansionary setting, and government spending should be aimed at decent work and tacking the climate and social care crises

- As pay rises won in a number of disputes show, a strengthened role for unions is the way to secure decent pay rises across the economy. The government needs to support union strength in workplaces across the economy and likewise extend the role for collective bargaining, including at sectoral or industry level. On top of this the minimum wage should be £10 now

- Public sector workers need treating fairly, rather than repeatedly targeted by austerity policies. Pay review bodies must lead on a changed mindset, escaping the zero-sum thinking that has caused more than a decade of stagnant real pay across both the private and public sectors.

Jobs and the pandemic economy

Employment and self-employment

Jobs continued to expand through to the end of 2021, and the expected sharp rise in unemployment after the end of the furlough scheme has thankfully not materialised.

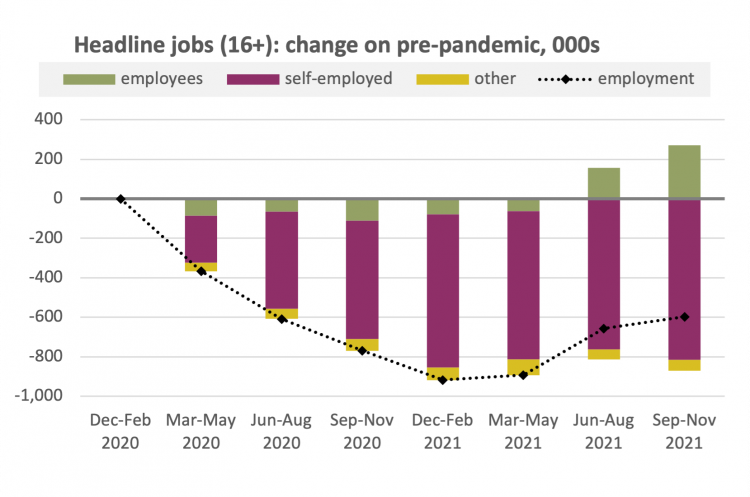

But jobs are still well down on the position before the pandemic, with self-employed workers hit very hard. Overall employment has fallen by 600,000 since just before the pandemic in Nov. 19 – Feb. 20; employee jobs are up 270,000 but self-employment is still down 820,000 (figure 1 below). The overall gain into the latest quarter was only 60,000, compared to 240,000 in the previous quarter, as a smaller rise in employee jobs (+120,000) was partly offset by a renewed fall in self-employment (-50,000).

- 1 Monetary Policy Report, February 2022: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/monetary-policy-report/2022/february/monetary-policy-report-february-2022.pdf

- 2 For example, GMB was able to secure a 19% pay deal for bin workers in Eastbourne in January 2022. Unite won disputes for bus workers in South Yorkshire, Mercedes Benz workers, and bus drivers in Nottingham for 10.7%, 13% and 8.3% in the same month.

Unemployment on other hand, following the rise of 400,000 through to the end of 2020, had by the end of 2021 returned to the pre pandemic level of 1.4 million. A large increase of 700,000 in inactivity explains how jobs can be down while unemployment is unchanged since the start of the pandemic. This increase is (partly) explained by higher student numbers, increased levels of long-term sickness, workers temporarily out of the labour market offset in part by lower numbers looking after families. 300,000 of the increase in inactivity is accounted for the 65+ age, going (mildly) against the trend since 2000 of more older workers staying in the workforce.

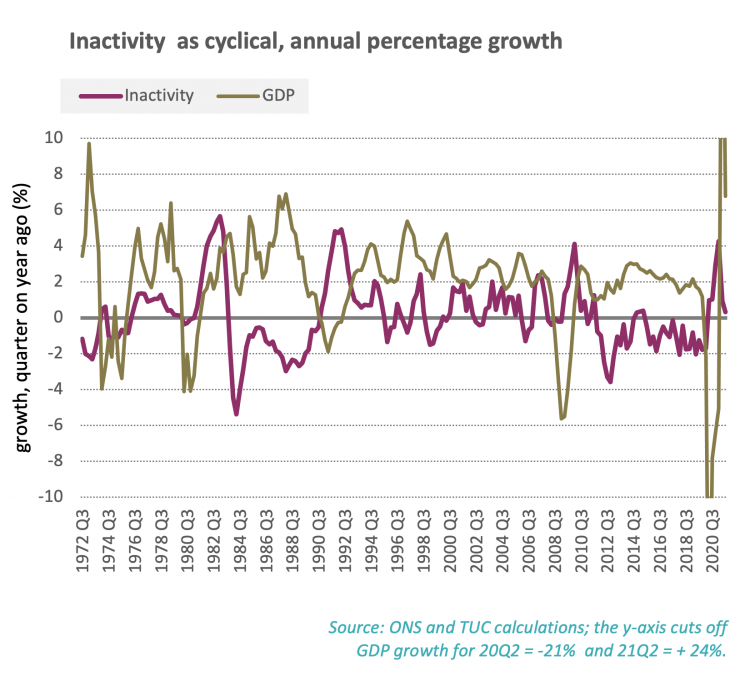

There is some discussion about this withdrawal of large numbers of workers from the labour market, with the implication that the supply of labour is therefore reduced (which compounds inflationary fears). But increases in inactivity are the norm in recession, and there is nothing atypical about the size of the increase over the course of the pandemic.

The chart below shows annual growth in GDP against the growth in the numbers of workers classified as inactive. The recent peak inactivity growth of 4.3% is similar to the peak growth in the wake of the global financial crisis (4.1% in 2010Q1), and a way below the growth in the early 90s recession (4.9% in 1992 Q2) and the early 80s recession (5.7% in 1983Q1).

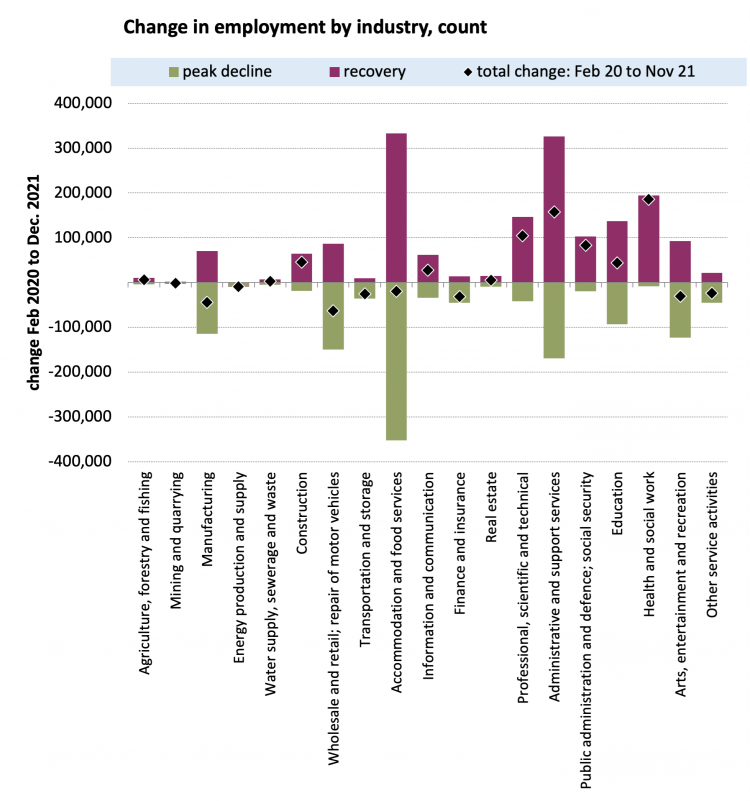

Industry

Beyond the headline figures, industry detail is available only for employees and not the self- employed. Payrolls (chart below) show all industries making up ground lost after the first lockdown, but a mixed position overall. Across a number of industries, jobs are still some way down on the pre-pandemic level: manufacturing (-1.8%), wholesale and retail (-1.4%), transport (-1.9%), finance (-2.9%), arts and entertainment (-5.1%) and other services (-4.3%).

Other industries have rebounded more strongly, and illustrate the emergence of the ‘pandemic economy’. Most obviously the biggest rise in jobs has been in health, where payrolls are up 190,000 or 4.8% (some of this increase may be temporary, and the ONS employer survey shows the increase lower at 110,000). ICT (+2.3%), administrative and support services (+6.5%), public administration (+6.4%) and professional services (+4.8%), likely at least in part reflect the need for new working arrangements, business processes and technologies through the pandemic.

Vacancies

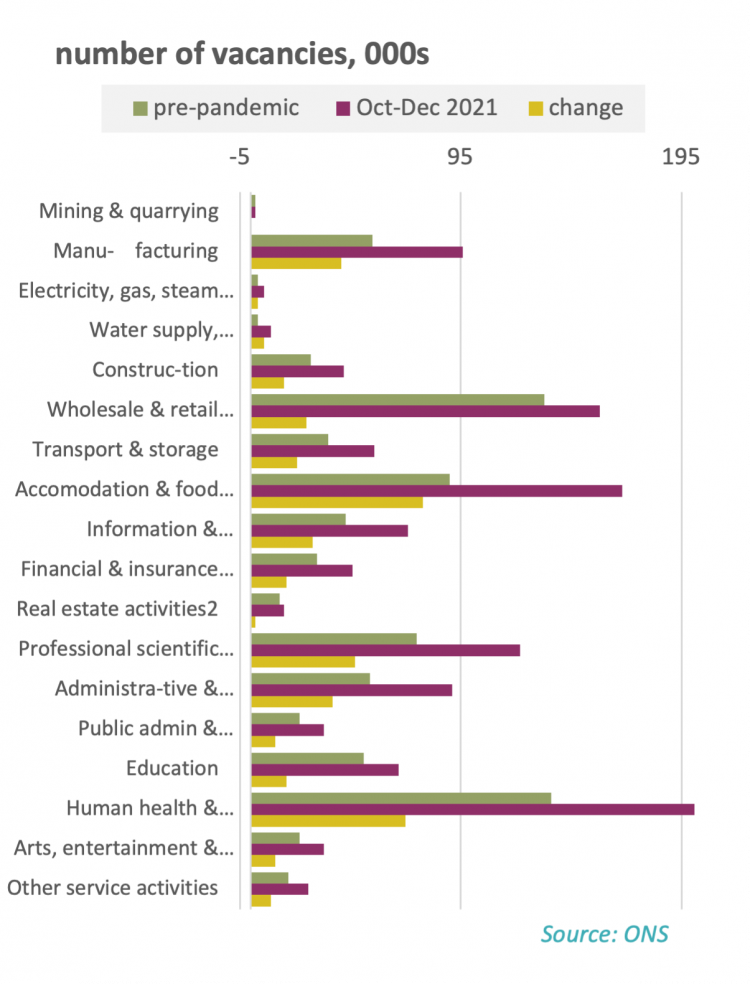

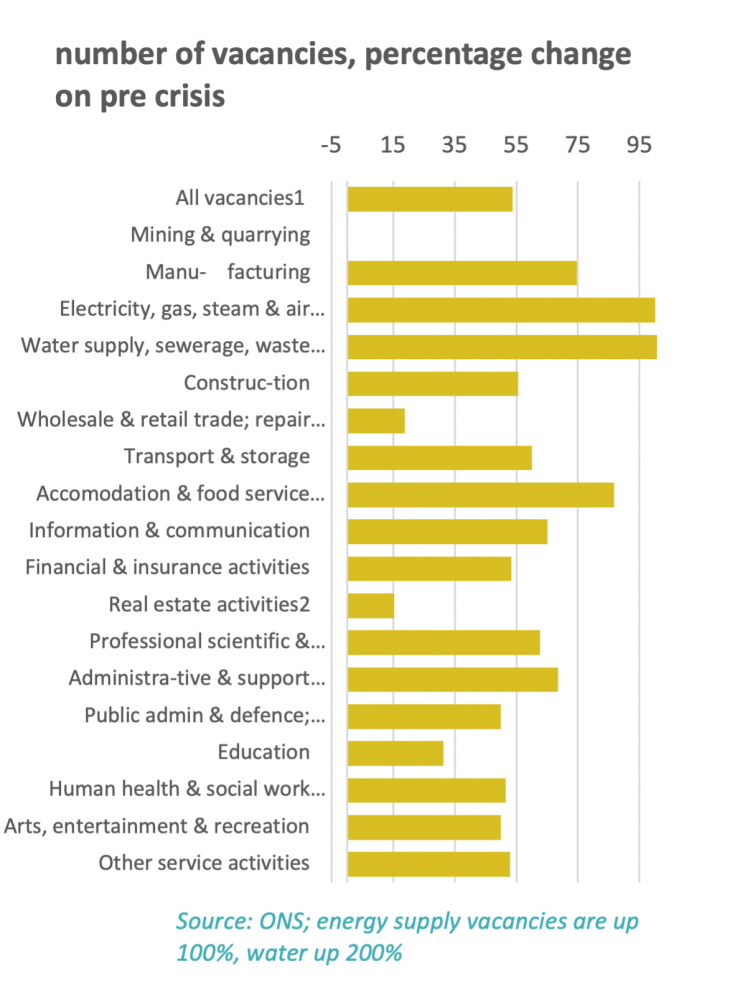

Widely reported each month are repeated records in the level of vacancies, running at around 800,000 before the pandemic and now up to 1,250,000. These vacancies still follow normal industry patterns (first chart below) , with wholesale and retail, accommodation and food, and health having the highest number of vacancies, and the latter two categories the highest increases. Percentage increases across all industries are strikingly uniform (second chart below). The areas where vacancies are disproportionately increased compared to norms are manufacturing, accommodation and food, ICT and professional and administrative services (energy and water supply increases are massive, but on very small overall numbers). Again these overlap to some extent with the areas where jobs are up most.

Pay

Headline pay and inflation

The cost of living crisis is double edged: rather than just rising inflation, it is also about slowing pay growth. Over the second half of 2021 headline (regular) pay growth has basically halved from 7.3% in June to 4.3% in October and 3.8% in November. This in large part reflects the unwinding of distortions in the figures caused by the furlough scheme. But ONS reckoned this process was done (at least at headline level) with the October figure,3 suggesting the slowdown of ½ percentage point into the latest month is reflecting real trends in workers’ pay.

In parallel inflation is increasing once more beyond policymaker expectations. In their November Monetary Policy Report the Bank of England expected inflation of 4.5% in both November and December. CPI inflation came in at 5.1% in November and 5.4% in December. RPI inflation was 7.1% in November and 7.5% in December. Both measures are at a thirty year high (CPI was last higher in Mar. 92 and RPI in Aug. 91).

With annual growth in pay now below inflation, real pay growth is once again in negative territory – the below chart shows the comparison for the month on year ago annual rate using CPI and RPI.4 On CPI real pay is down 1.5 per cent, and this is the largest decline for eight years. On RPI real pay is down 3.4 per cent, the largest decline for a decade.

- 3 “These temporary factors have largely worked their way out of the latest growth rates, however, a small amount of base effect for certain sectors may still be present”: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/december2021

- 4 The TUC have strongly resisted official attempts to dismantle the RPI

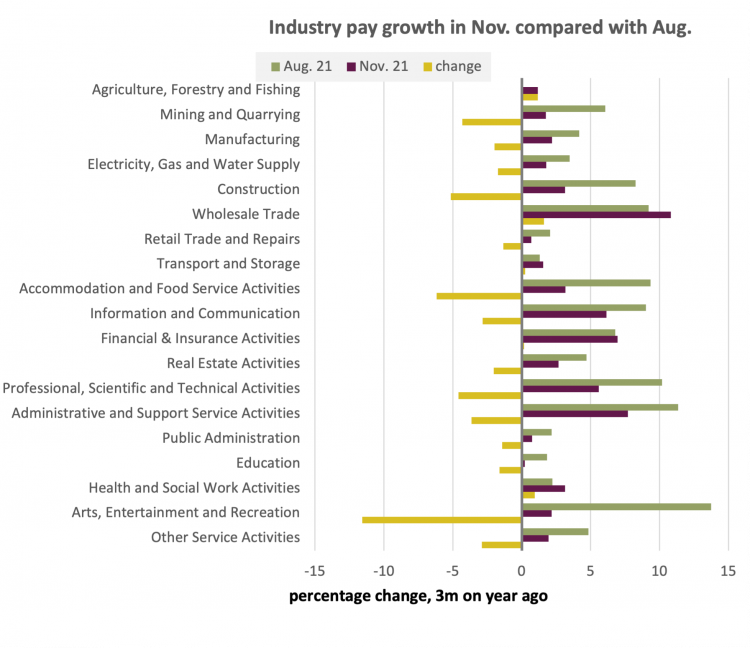

Industry story

In spite of jobs gains and high vacancies, the slowdown in pay growth is seen pretty much across all industries. Again this is likely driven by distortions working through the level measures. So while the figures (on the first chart over the page comparing the latest month with three months earlier) exaggerate the extent of the slowdown, beyond any distortions for basically all industries pay growth is on a downward trajectory.

An aggregate measure for the private sector (not shown) shows pay growth slowing to 4.1% in November from 4.7% in October. This suggests pay growth is weaker than expected by the Bank of England – the Minutes of the December meeting of the Monetary Policy Committee reported “Bank staff estimate[ing] that private sector regular pay growth had remained at around 4½%, above pre-pandemic rates of around 3%”. The aggregate measure for the public sector fell to 2.6% from 2.7%.

Nonetheless there are a handful of industries where pay growth in November was higher than the norm. Wholesale trade, ICT, finance, professional and administrative services, all show real pay growth (the second figure on the next page) above zero.

Again these overlap very heavily with the ‘pandemic industries’, The large gains in the wholesale industries are of note given the intensified used of on-line shopping and anecdotal evidence of better than normal settlements; conversely retail trades have seen among the largest real pay falls.

But the big exception here are the public sector industries. While demand for labour has been high, this is not reflected in pay packets. Education and public administration are the two industries with the largest real pay falls. Critical to the response to the pandemic, this cannot be right.

Survey evidence on pay expectations

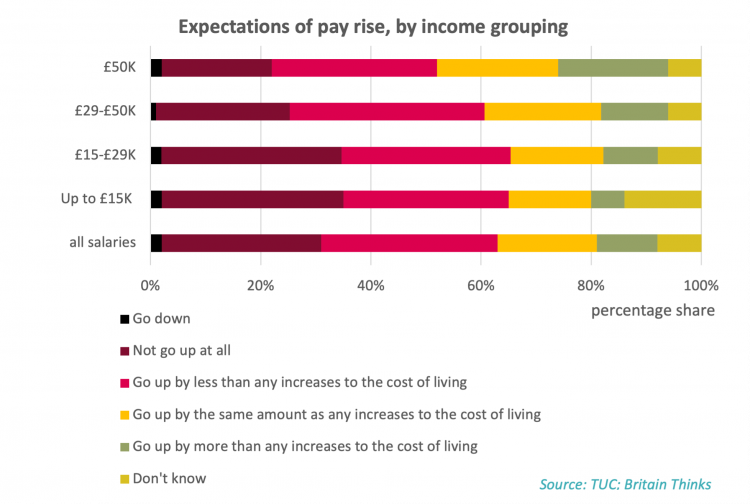

A TUC survey conducted by ‘Britain Thinks’ found that overall 2/3 of workers did not expect pay rises to keep pace with increases in the cost of living; half of these did not expect pay to go up at all.5 Expectations are more pessimistic among the lowest earners, where 33% don’t expect pay to go up at all. Even for high earners only 20% expect pay to rise faster than inflation, with only 6% of low earners expecting likewise.

- 5 On behalf of the TUC, BritainThinks conducted a nationally representative online survey of 2,209 workers in England and Wales between 14th-20th December 2021.

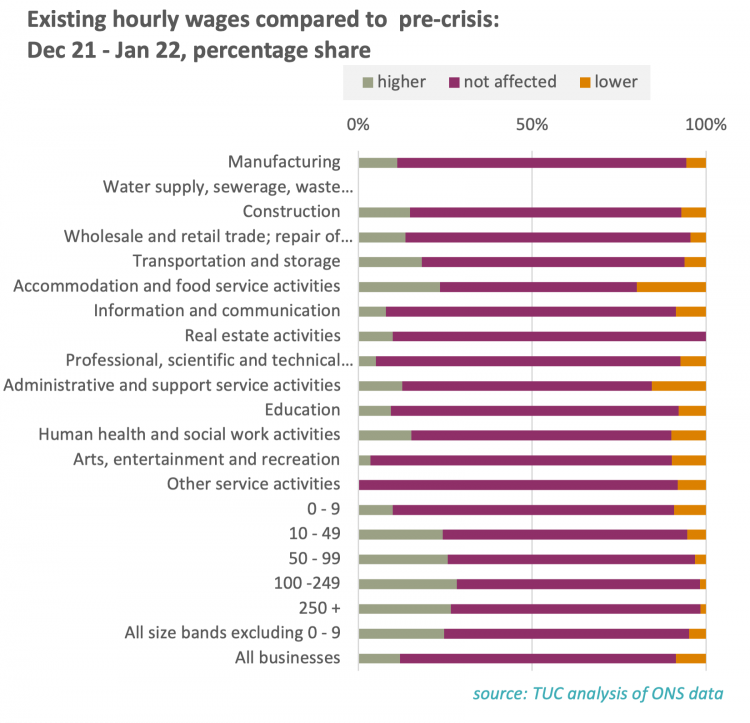

The ONS ‘Business insights and impacts on the UK economy’ dataset shows over Dec. 21/Jan. 22 only 7.8% of companies considered wages were higher than normal, with 5.7% saying they were lower than normal. On the other hand 52% said wages had not been affected by the pandemic. Worse: this is a deterioration compared to Nov./Dec. 21 when 9.3% thought pay higher than expected and 4.5% lower than expected. The chart below shows the latest results according to industries and company size.

One factor is company size, with 21.4% of larger companies thinking pay higher than normal and 4.3% of companies thinking lower – though this is still a deterioration on the previous results.

Trade unions winning pay rises

Among these gloomy figures, specific workplaces have won inflation-busting pay rises due to empowered unions.

In Eastbourne, bin workers were managed to secure a 19% pay rise following six days of strike action. Gary Palmer, the local GMB organiser, said “Other employers should take note, GMB members know their own worth and are not scared to take bosses on.”

In January, Mercedes Benz Retail Group workers based across the South East won a 13% pay rise. When they entered negotiations, management had offered no pay rise, but this was over-turned after Unite members voted to take four days of strike action.

In the North, bus workers in both South Yorkshire and Nottingham secured a pay rise of 10.7% and 8.3%-9.3% respectively after both workplaces threatened strike action.

These stories run against the grain of the pay story in wider society, highlighting that empowered trade unions are essential for creating significant and sustained wage growth.

Conclusions and recommendations

The cost-of-living crisis is now a major threat to the livelihood of too many workers. Frances O’Grady has asked

“The Chancellor must come forward with a plan to tackle the cost-of-living crisis. Working people need stronger rights to bargain for fair pay increases. And families need more help with rising bills through universal credit."

In the macroeconomic policy context, we reject the idea that higher pay will intensify inflationary pressures, when high pay is the best solution to the cost of living crisis.

Workers have endured the worst pay crisis for at least two centuries. Going forwards higher pay will be needed to support spending and so strengthen the economy. Low pay will cut spending and further weaken the economy.

The noise around bottlenecks and shortages should not be mistaken for improved conditions for workers across the board. Some workers in some industries may have done well from the pandemic economy – but too many have not and especially those in the public sector.

The pandemic has taught us the importance and power of government action to protect the economy and workers. But the economy was in a bad way ahead of the pandemic, and it was always wishful thinking that all will be put right alongside the pandemic ending (to the extent that it is ending). Policymakers need to keep monetary and fiscal policy on an expansionary setting. The way to set things right is to build back better, to aim government spending at decent work, and tackle the climate and social care crises.

We are seeing unions winning pay rises in many disputes. A bigger role for unions is the way to secure decent pay rises across the economy. The government needs to support union strength in workplaces across the economy and likewise extend the role for collective bargaining, including at sectoral or industry level. On top of this the minimum wage should be £10 now.

Public sector workers need treating fairly, rather than repeatedly targeted by austerity policies. Pay review bodies must lead on a changed mindset, escaping the zero-sum game thinking that has caused the decline in real pay across the board.

From the start of the pandemic the TUC has been calling on the government to convene a national recovery council bringing together trade unions, government and employers immediately to work together to discuss ways to support workers and firms in the cost of living crisis and equally how we build back better and fairer.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox