Jobs and recovery monitor - gender and pay

In this edition of our jobs and recovery monitor we are looking at the impact of gender on wages and employment, as well as the impact of the high cost of childcare on women in work.

Women are less likely to fully participate in the labour market compared to men and are more likely to be low paid. This is largely due to caring responsibilities, which disproportionately fall upon women.

According to TUC analysis, more than 1.46 million women are unable to work alongside their family commitments, compared to around 230,000 men. One in 10 women in their 30s – more than 450,000 women – is out of the labour market because of caring responsibilities compared to just one in 100 men in their 30s. Women are 10 times more likely than men to be unable to work due to family commitments at home.

In order to address this, the TUC demands universal, flexible, high-quality childcare that is available to all from the point at which paid maternity or parental leave ends, flexible working rights from day one, and a reform of shared parental leave.

Headlines

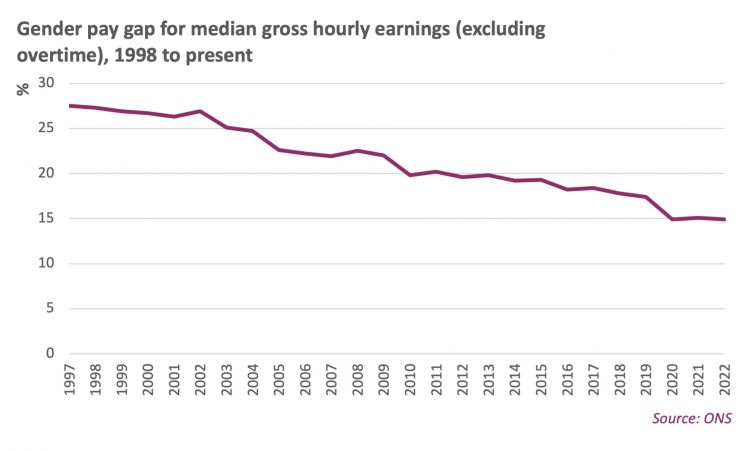

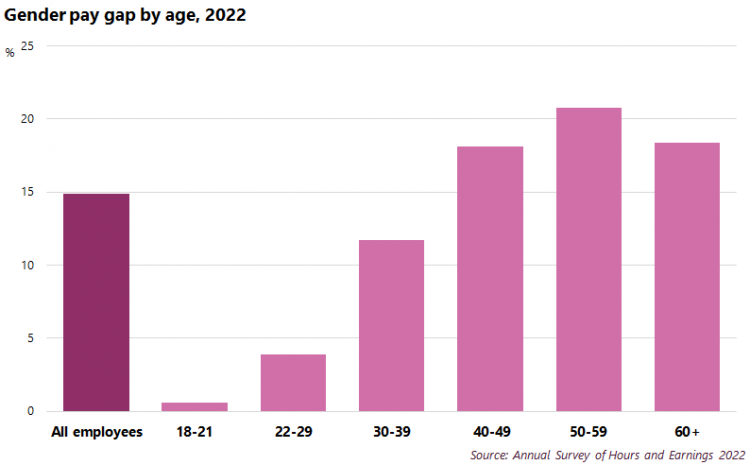

The gender pay gap is currently 14.9 per cent as of February 2023. The pay gap is highest for women in their 50s, who face a Gender Pay Gap of over 20 per cent.

The gender pension gap is currently 38 per cent, and is as high as 80 per cent in certain industries, such as retail, wholesale and manufacturing.

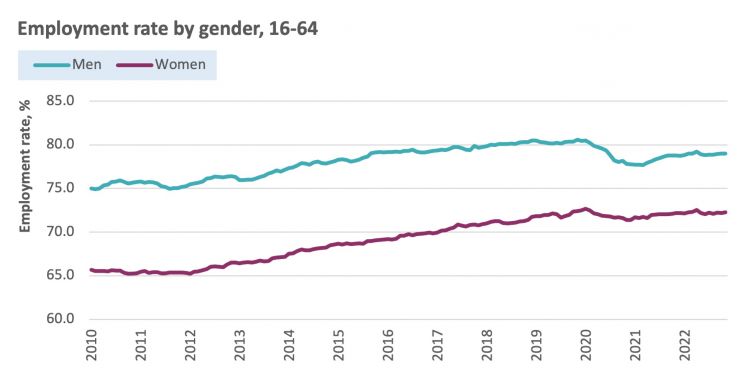

Employment has stagnated for both genders, and women are still less likely to be in paid work than men. For men, employment fell drastically during COVID and has yet to recover. It is currently lower than it was in mid-2015, and growth has tapered off. Among women, the employment rate remains at just 72.3 per cent, compared to 79.0 per cent for men.

A key reason why less women are in employment is due to caring responsibilities. Women are 7 times as likely to be economically inactive due to looking after the home or family. This rises to 10 times more likely when comparing women and men in their 30s.

While there has been a strong trend of women moving from full-time caring responsibilities to paid employment over the last three decades, this has stalled in the past six months. We have also warned that the staffing crisis in social care was making it harder for women to stay in work alongside their caring responsibilities.

In addition, the cost of childcare has become prohibitively expensive, with full-time nursery for children under two costing an average of £14,200 a year. This is leading to more women exiting the workforce to avoid these high childcare costs.

Women are also both more likely be earning below the Living Wage Foundation’s Real Living Wage, and to be earning under the Government’s minimum wage. This gap is due in part to women accounting for three quarters of all part-time workers, as part-time work tends to be low paid.

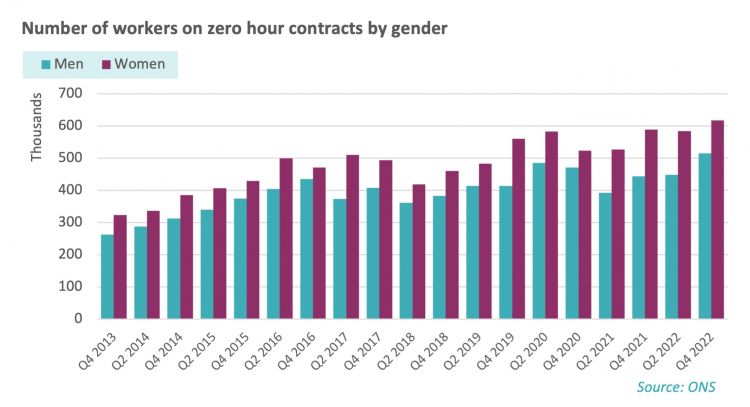

Finally, women are more likely to be employed on zero-hour contracts than men, and the number of both men and women employed on these contracts has grown in the last year. There are now more than 1.1 million workers employed on zero-hour contracts, which is the highest since records began.

Looking at gender and the labour market

The Gender Pay Gap

The gender pay gap for all employees currently stands at 14.9 per cent. This pay gap means that working women must wait 54 days – nearly eight weeks, or two months – before they stop working for free. In 2023, Women’s Pay Day fell on 23rd February 2023.1

The gap between men and women’s earnings has been steadily shrinking since records began in 1997, and has dropped from 27.5 per cent to 14.9 per cent over the past 25 years. However, progress has significantly slowed since the pandemic

- 1 Gender pay gap means women work for free for two months of the year. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/gender-pay-gap-means-women-work-free-two-months-year-tuc

TUC analysis found that the pay gap grows throughout a woman’s working life and is largest for older women. The age group most affected is women aged between 50 and 59 who experience a gender pay gap of 20.8 per cent. This means they earn more than one-fifth less than men in the same age bracket.2

- 2 Ibid

One reason for the widening pay gap as women get older could be the higher expectation to take on care responsibilities. And older women take a financial hit for balancing work alongside caring for older relatives as well as children and grandchildren.

There is also an industrial component, and women working in the finance and education sectors experience the largest gender pay gap of 31.2 per cent and 22.2 per cent respectively.3 The pay gap in education is particularly relevant as teaching staff in both NEU and UCU have been on strike this year over pay and conditions, and have more strike action planned for the following months.

These issues compound over women’s entire working lives and, combined with the increased likelihood of women working part-time or taking time out of work due to caring responsibilities, means that women reach retirement with much smaller pension pots than their male counterparts. The average gender pension gap currently stands at 38%, which is more than twice the gender pay gap. Furthermore, in several industries, women retire with pension pots worth 80 per cent less than that of their male counterparts.4

The gender pay gap intersects with other inequalities. Previous TUC analysis has shown how the disability pay gap intersects with the gender pay gap, with the pay gap being widest among disabled women and non-disabled men. Median hourly pay for disabled women (£11.33) is £3.93 less than it is for non-disabled men (£15.25).5

Levels of employment

While employment levels have been historically higher among men, they were relatively more negatively affected by COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdowns. This initial fall for employment among men has made a slight improvement, but it is far from what is needed to bring the male employment rate back to its pre-COVID peak.

- 3 Ibid

- 4 Gender pensions gap means retired women go the equivalent of four and a half months each year without a pension. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/gender-pensions-gap-means-retired-women-go-equivalent-four-and-half-months-each-year-without

- 5 Disabled workers jobs and pay monitor. Available at https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-11/Jobs-and-pay-monitor-disability-2022.pdf

December to February employment rates for men stand at 79.0 per cent, up 0.2 per cent on the year and 0.1 per cent on the previous quarter, and 1.6 per cent below its pre-COVID peak. For women, the employment rate is largely unchanged at 72.3 per cent, 0.1 per cent up on the same period last year and 0.2 per cent up on the quarter, but 0.4 per cent below its pre-COVID peak. The unemployment rates for men and women stand at 3.9 and 3.7 per cent respectively, both down 0.3 per cent on the same period a year ago.

The charts above show employment levels and rates for men and women since 2010. It highlights that the narrowing of the gender employment gap is largely due to the negative impact that COVID-19 had on the employment rate for men. For both genders, we see that employment growth has fallen below its pre-COVID level. For men, employment is lower now than it was in mid-2015.

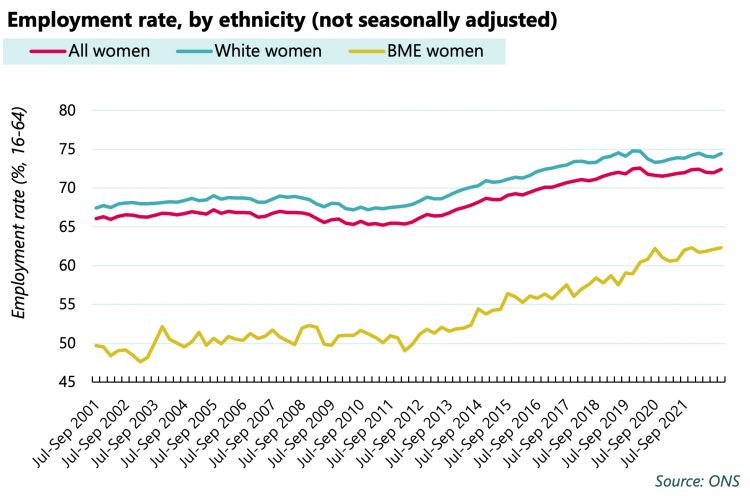

The pandemic has also had a detrimental impact on employment among BME workers who have an employment gap of 8.2 per cent with their white counterparts. BME women have a particularly low employment rate of only 62.3 per cent.6

- 6 Jobs monitor - the impact of the pandemic on BME employment. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-monitor-impact-pandemic-bme-employment

However, BME employment rates have been increasing since the pandemic, and this change is being driven by women. The employment rate for BME women is now at a record high, however it still lags far behind the employment rate for white women and men.

Economic inactivity and caring responsibilities

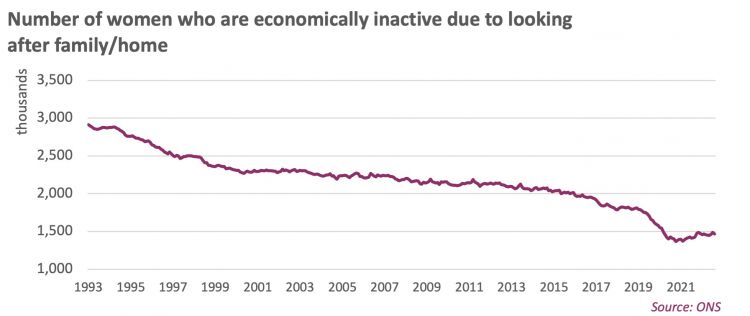

Over recent decades, there has been a trend of more women entering the workplace and fewer taking on full-time caring responsibilities. In 1993, almost 3 million women were out of work due to caring responsibilities. Over the past three decades, this figure has been halved to stand at roughly 1.5 million.

Despite this, women are still more likely to be economically inactive compared to their male counterparts, and this figure is even worse for BME women, who are almost 50 per cent more likely to be economically inactive compared to the average workers.7 Women in their 30s are more than 10 times more likely to be economically inactive due to looking after the family or home than men in the same age bracket.

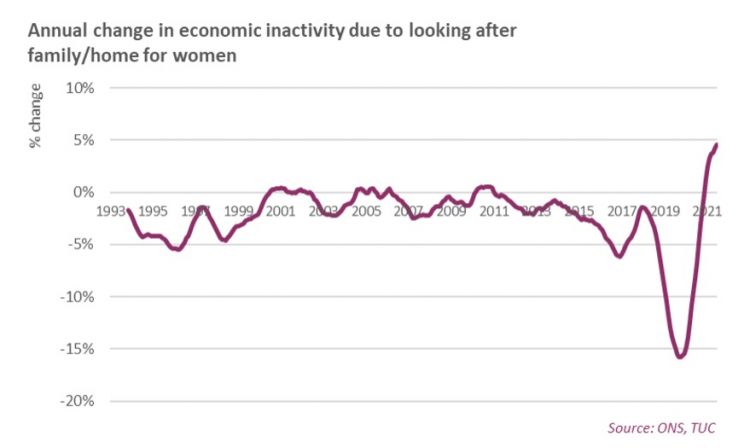

In the pandemic, we saw a sharp downwards turn in the number of women who were economically inactive due to caring responsibilities. At one point during the pandemic, the inactivity rate due to looking after the home or family fell by 15% on the previous year – which is the most dramatic fall since records began.

This may have been due to the rise in remote working, as women may have felt that they could better balance caring responsibilities with their jobs when working from home. However, in practice, women took on a disproportionate and unmanageable amount of responsibility for childcare and housework during the pandemic, with female parents saying they spend seven hours in an average weekday on childcare, compared with five hours for male parents.8 In a TUC survey of working mums, 65 per cent said they are juggling working from home with caring commitments – and nine in ten said the disruption had a negative impact on their mental health, with increasing levels of stress and anxiety.9

- 7 Jobs monitor - the impact of the pandemic on BME employment. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-monitor-impact-pandemic-bme-employment

- 8 Women doing more childcare under lockdown but men more likely to feel their jobs are suffering. Available at: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/women-doing-more-childcare-under-lockdown-but-men-more-likely-to-feel-their-jobs-are-suffering

- 9 Working mums and COVID-19: paying the price. Available at: WorkingMums.pdf (tuc.org.uk)

However, since the economy re-opened post-COVID, the trend towards women moving away from full-time caring responsibilities has reversed, with more women leaving the workforce for this reason. This may reflect the limitations of current flexible working arrangements and cost of childcare, which don’t yet offer the flexibility and support which working parents need. In a TUC survey of working mums, 18 per cent of respondents said that they been forced to reduce their working hours due to childcare responsibilities, and 7 per cent said that they were forced to take unpaid leave to care for their families.10

Cost of childcare

We know that caring responsibilities are a significant factor limiting women’s participation and progression in the labour market. A significantly higher portion of women are economically inactive or work part-time when compared to men. Furthermore, it is estimated that 1.7 million women are prevented from taking on more hours of paid work due to childcare issues, resulting in a loss of up to £28.2 bn in economic output each year.11

TUC analysis found that childcare fees have shot up throughout England over the past decade – with full-time nursery for children under two costing an average of £14,200 a year. Today, nurseries in every English region are, on average, charging parents over £1,000 a month, with £2,000 fees ‘around the corner’.12

The UK spends less than 0.1% of GDP on childcare, the second lowest investment in the OECD.13 And we now have the second highest childcare costs among leading economies.14

The charity Pregnant then Screwed found that three in four mums (76 per cent) who pay for childcare say it no longer makes financial sense for them to work. Furthermore, 1 in 4 parents (26%) who paid for childcare, say that the cost is more than 75% of their take home pay, and a further third of parents said they had taken on some form of debt to deal with the cost of childcare. 15

Low paid workers

In 2022, almost 3.5 million workers (12.2 per cent of the workforce) earn less than the Living Wage Foundation’s Real Living Wage, which currently stands at £10.90 an hour and £11.95 an hour in London. Women are overall more likely to be paid less than the Real Living Wage – 14.6 per cent of women earn below this figure, compared to 9.9 per cent of men. Part-time workers are most likely to be low paid, with 31.2 per cent of men and 24.5 per cent of women working part-time earning less than the Real Living Wage.16 It is important to note that women are almost three times more likely to work part-time compared to men.17

- 10 Ibid

- 11 Spring Budget 2022 Pre-Budget Briefing: Childcare and Gender. Available at: https://wbg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Childcare-and-gender-PBB-Spring-2022-1.pdf

- 12 TUC calls for universal free childcare for pre-school children as nursery bills “skyrocket” across England. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/tuc-calls-universal-free-childcare-pre-school-children-nursery-bills-skyrocket-across-england

- 13 CPP | Women in the labour market (progressive-policy.net)

- 14 Benefits and wages - Net childcare costs - OECD Data

- 15 https://pregnantthenscrewed.com/three-quarters-of-mothers-who-pay-for-c…

- 16 TUC analysis of ONS figures, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/datasets/numberandproportionofemployeejobswithhourlypaybelowthelivingwage

- 17 TUC analysis of ONS figures, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/datasets/fulltimeparttimeandtemporaryworkersseasonallyadjustedemp01sa

Women are also more likely to be paid below the legal minimum wage – which is currently £9.50 for workers who are aged 23 and older. Currently 2.1 per cent of women are paid less than this, compared to 1.4 per cent of men.

Furthermore, TUC analysis shows that women make up two-thirds of those employed in the ten lowest paid occupations, and only 4-in-10 of those in the ten highest paid occupations.

Zero-hour contracts

The number of people on zero-hour contracts has exploded in the last decade. With no fixed hours each week it's impossible for a large section of the workforce to plan or save for the future. Zero-hour workers are some of the most insecure and vulnerable people in the workforce.

After the pandemic, we’ve seen a steady rise in the number of workers on zero-hour contracts. As of December 2022, there are more workers on zero-hour contracts than ever before. Currently, more than 600,000 women are employed on these contracts and 500,000 men, with a total of more than 1.1 million workers employed this way.

There has always been a gender angle to zero-hour contracts, with women being more likely be on these insecure contracts, and little has been done to address this divide. In addition, BME workers, especially BME women, are more likely to be employed on zero-hours contracts. Almost 5% of BME women in the workforce - one in twenty – are employed on a zero-hour contract, compared to the average figure of just over 3%.18

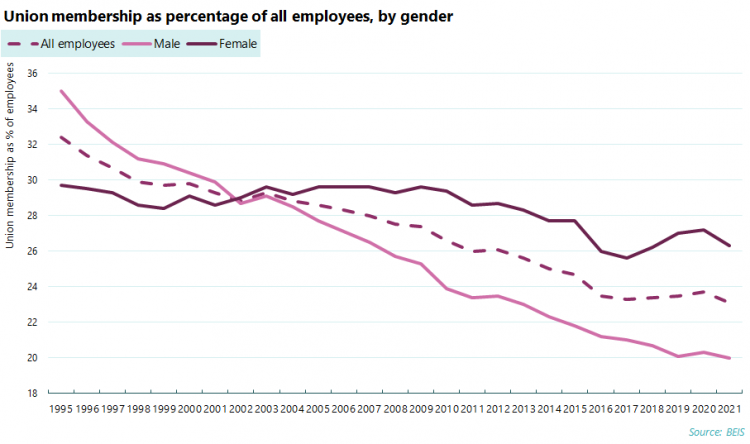

Trade Union density and membership

In the early 2000s, the percentage of women who were Trade Union members overtook men for the first time. This trend has continued right to the present day, and now just over 26% per cent of female employees are Trade Union members, compared to 20 per cent of male employees. Today, union density is higher for women than men, and is significantly higher in the public sector compared to the private sector.

- 18 Jobs monitor - the impact of the pandemic on BME employment. Available at: https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/jobs-monitor-impact-pandemic-bme-employment

In recent months, we have seen teachers, nurses and civil servants successfully balloting for strike action and going on strike. These are workplaces with a disproportionate number of female staff, as well as high levels of diversity. The teaching workforce is 75% women, with women accounting for 89% of support staff. In the NHS, 77% of workers are women and 82% are women in social care.

A large number of unions are striking on 15th March 2023, which is the same day as Jeremy Hunt is revealing his Budget. London underground workers, university lecturers, civil servants, teachers, and more have strike action planned around Budget Day.

Conclusions and recommendations

What needs to happen?

At the TUC we are calling for several policies that will help support all workers, and particularly women as we build back better, fairer and more equal from this crisis:

Workers’ rights

- Introduce universal funded, high-quality childcare, available to all, free at the point of use. This would begin when paid maternity leave ends and would enable women to stay in work when they have children.

- Create greater flexibility in all jobs. There should be a duty on employers to advertise all jobs with possible flexible working options. And all workers should have a day one right to work flexibly – not just the right to ask - unless the employer can properly justify why this is not possible. Workers should have the right to appeal any rejections. And there shouldn’t be a limit on how many times a worker can ask for flexible working arrangements in a single year.

- Reform Shared Parental Leave, guaranteeing a day one, individual right to shared parental leave for all workers from day one in the job, and paid at least at the Real Living Wage rate. The government should publish its evaluation of shared parental leave, which began in 2018.

- Strengthen gender pay gap reporting: From 1 April 2017, the government ruled that large companies must publish information about the difference between average male and female earnings. The TUC believes the government must go further and wants employers to be made to carry out equal pay audits, and to produce action plans to close the pay gap in their workplace. The TUC also wants companies that fail to comply with the law to receive instant fines. This should also be extended to cover ethnicity and disability pay gaps.

- Ten days' paid carers leave, from day one in a job, for all parents. Currently parents have no statutory right to paid leave to look after their children.

- Fix the staffing crisis in social care: There are a record 165,000 vacancies across adult social care. The TUC believes this is placing a huge strain on women with caring responsibilities for family members. The TUC says the government must work with unions and employers to tackle widespread insecure work and poverty pay in the sector which are driving high staff turnover rates. Ban zero-hours contracts which particularly affect key workers in health and social care, and wholesale and retail, many of whom are women.

Supporting and improving people’s incomes

- Government must raise the minimum wage for all workers to £15 per hour as soon as possible.

- Government should give public sector workers a real terms pay rise

- An increase in sick pay to at least the level of the Real Living Wage, for everyone in work, to ensure workers can afford to self-isolate if they need to.

- Universal credit must be completely reformed. In the short-term, this will involve raising the basic level of universal credit and legacy benefits, including jobseekers allowance and employment and support allowance, to at least 80 per cent of the national living wage (around £260 per week); removing the two child cap and significantly increasing benefit payments for children; removing the benefits cap; ending No Recourse to Public Funds; and ending all savings criteria.

Childcare provision

- Universal, flexible, high-quality childcare that is available to all from the point at which paid maternity or parental leave ends.

- A new deal for the childcare workforce, starting with a new sectoral minimum wage.

- A new social partnership forum in childcare, bringing together unions, government, employers as a first step towards a fair pay agreement that covers the sector.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox