Insecure work

The entry of a new Prime Minister into Downing Street provides a fresh opportunity to tackle the scourge of insecure work.

This report examines the extent of insecure work in the UK.

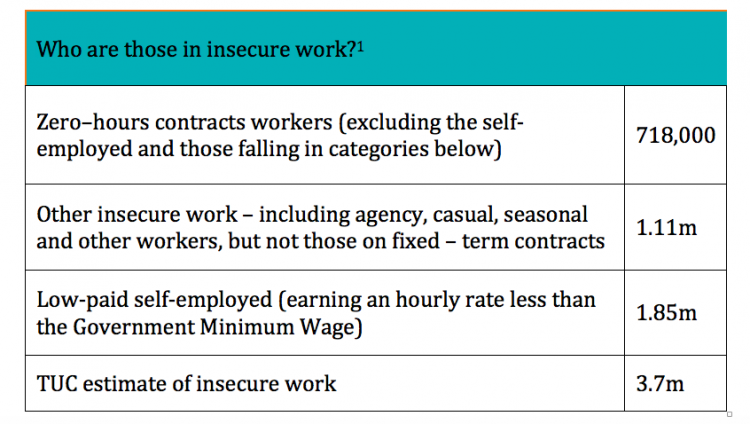

It finds that 3.7 million people are in insecure work due to being among the ranks of the low-paid self-employed, agency, casual and seasonal workers, or on zero-hours contracts.

This is one in nine of the workforce.

Insecure work is widespread in certain occupations, notably caring and leisure, the skilled trades and elementary roles such as kitchen assistants and security guards.

But it has a profound effect on the workers involved who often have no idea what hours they are going to work or how they will pay their bills.

Despite this, there has been little decisive action against insecure work.

What is required is a significant shift in workplace rights to ensure that all that all workers have a decent floor of rights and can benefit from the protection of a union.

New analysis by the TUC shows that at least 3.7 million workers in the UK, around one in nine of the workforce, are in insecure work. Insecure work is not restricted to any particular corner of the country. It is widespread.

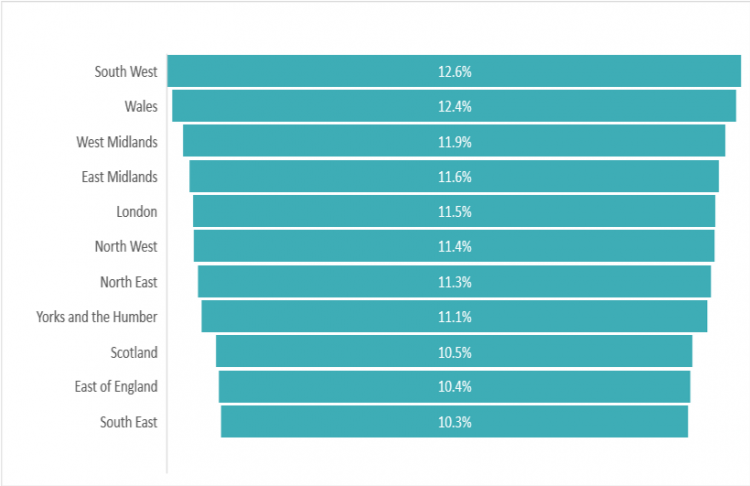

In every region of England and in Wales and Scotland, insecure workers make up at least 10 per cent of the workforce.

These include agency, casual and seasonal workers, those whose main job is on a zero-hours contract and self-employed workers who are paid less than the National Living Wage.

Insecure work has a huge impact on those who endure it.

Those in insecure work often don’t know what hours they will work (causing chaos with arrangements like childcare) or whether they will be able to pay their next bills.

Many also miss out on rights and protections that many of us take for granted. These include being able to return to the same job after having a baby and the right to sick pay when they cannot work.

This is blighting the lives of millions of workers. So at the top of the new Prime Minister’s to-do list should be the task of tackling the shameful rise and persistence of insecure work.

People often associate insecure work with the growth of the ‘gig economy’ – app-based services like Uber and Deliveroo. And, as we have shown , this type of work is growing, though often it is undertaken to top-up insufficient wages from other forms of work.

But insecurity is also widespread in jobs that have been around for years.

Our figures show that insecure work extends to:

- one in five (20 per cent) of those classed as elementary roles which includes kitchen assistants, security guards and farm workers

- one in six (17 per cent) of those in caring and leisure roles

- one in five (19 per cent) of those working in skilled trades.

This is nothing to do with billionaire tech boffins in Silicon Valley. It is down to the reluctance of ministers to take action to stop workers from being exploited.

For decent work has been the forgotten issue of the past few years.

The government’s flagship workers’ rights initiative, the Good Work Plan, was inadequate on paper and implementation has been glacial.

The new Prime Minister needs to get a grip of this situation.

We need a new deal for working people so that every worker gets respect, and every job is a good job.

This means:

- a ban on zero-hours contracts and bogus self-employment

- a decent floor of rights for all workers and the return of protection against unfair dismissal to millions of working people

- ensuring workers enjoy the same basic rights as employees, including redundancy pay and family-friendly rights

- new rights so that workers can be protected by a union in every workplace, and when we use social media, so that nobody has to face their employer alone

- new rights for workers to bargain through unions for fair pay and conditions across industries, ending the race to the bottom.

Insecure work pushes an unfair amount of risk onto the individual worker: they often don’t know when they will be working and for how long and how much they will be paid.

Often they miss out on key workplace rights such as:

- the right to return to the same job after maternity, adoption, paternity or shared parental leave

- the right to request flexible working

- the right to protection from unfair dismissal or statutory redundancy pay

- and many insecure workers miss out on key social security rights such as statutory sick pay, full maternity pay and paternity pay.

When estimating the number of people in insecure work the TUC includes:

- those on zero-hours contracts who risk missing out on access to key rights and protections at work, lack income security and face lower rates of pay

- agency, casual and seasonal workers (but not those on fixed – term contracts) who risk missing out on key workplace rights and protections and face lower rates of pay

- the low-paid self-employed who miss out on key rights and protections that come with being an employee and cannot afford to provide a safety net for when they are unable to work.

More detail on workplace rights can be found in Annexe 1.

Insecure work is neither brand new nor is it limited to a small corner of the economy.

Indeed, far from being a niche issue, the TUC’s analysis shows that there are currently 3.7 million people in insecure work, some one in nine workers.

Table 1 - How the TUC estimates the number of people in in insecure work

And insecure work is not something that affects just one corner of the country. In every English region, and in Wales and Scotland, at least one in ten workers is experiencing insecure work.

Chart 1 – Proportion in insecure work – region/nation

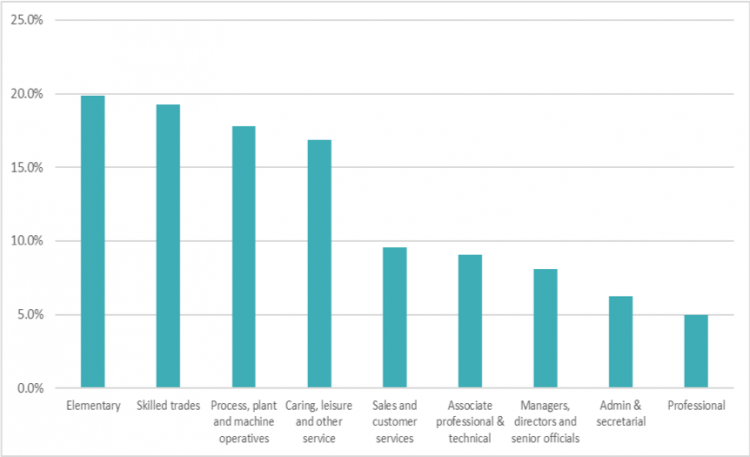

Insecure work is not just found among app-based occupations, such as food delivery and taxi driving, though it is rife in these sectors. It is also widespread in many long-standing occupations.

Chart 2 - Proportion in insecure work - by occupation

This includes caring and leisure where nearly half a million of its three million workers, some 17 per cent are in insecure work.

Likewise, one in five of those in elementary roles are in insecure work, as are 19 per cent of those in the skilled trades and 18 per cent of process, plant and machine operatives.

At the other end of the scale, one in 20 professionals and six per cent in administrative and secretarial roles are in insecure work.

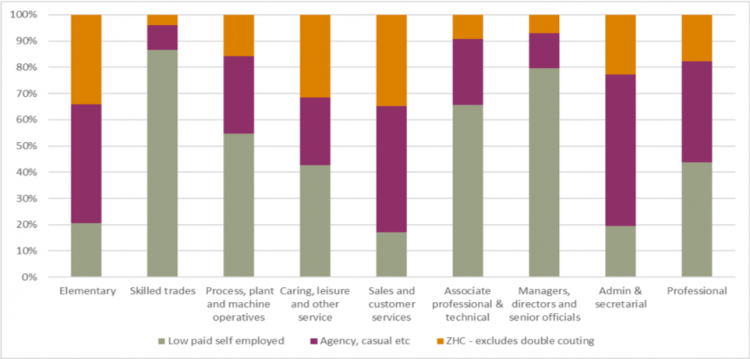

Chart 3 shows how the type of insecure work varies in each occupation.

For example, among those classed as elementary workers, the most significant driver of insecure work is the 45 per cent who are agency or casual workers.

The highest proportion of those classed as insecure workers due to the widespread use of zero hours contracts is found in sales and customer services (35 per cent).

Chart 3 – Contribution of form of insecure work

Among those in skilled trades, 87 per cent of insecure workers are classified as such due to being self-employed workers earning less than the National Living Wage.

What this tells us is that insecure work is widespread. And while it takes subtly different forms in different occupations, it requires concerted political will to tackle it.

We know that millions of workers desperately need a new deal that gives them access to decent work.

But the government’s response so far to the scourge of insecure work has been inadequate on paper and glacial to put into practice.

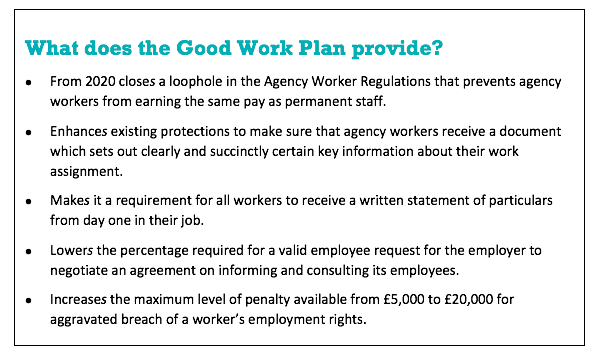

Following trade union campaigning, the government’s Good Work Plan has resulted in some small changes to policy, that could help protect insecure workers – listed in the box below.

But there are huge areas where the government has taken no action and needs to act now. We’re calling for:

- a ban on zero-hours contracts and bogus self-employment

- a decent floor of rights for all workers and the return of protection against unfair dismissal to millions of working people.

- ensuring workers enjoy the same basic rights as employees, including redundancy pay and family-friendly rights.

- new rights so that workers can be protected by a union in every workplace, and when we use social media, so that nobody has to face their employer alone.

- new rights for workers to bargain through unions for fair pay and conditions across industries, ending the race to the bottom.

We set out more detail in each of these areas below.

ZHCs and false self-employment

Zero-hours contracts, in which workers are not guaranteed work, are a one-sided form of flexibility.

Workers have little idea how much they will earn from one week to the next.

Many work long hours, worried that turning down shifts will mean they won’t get future work. Others are unable to cobble together enough work to pay the bills.

The government’s response is to propose giving workers on these contracts the “right to request” a predictable and stable contract after six months in the role.

This is an extremely weak right, which does nothing to guarantee job security for people working on zero-hours contracts.

The right to ask your employer a question is close to meaningless. This right has yet to be introduced.

The TUC wants a ban on zero-hours contracts.

We are clear that employment rights are of little use if they are not enforced.

Robust enforcement, as well as a floor of basic rights (see below), is also required to tackle the problem of employers misclassifying workers as self-employed

The Taylor Review that led to the Good Work Plan recommended that the state take responsibility for enforcing a “core” set of rights including holiday pay. But the government has already watered this down to enforcement of rights relating to “vulnerable workers”.

Meanwhile, it is not clear that enforcement agencies will have enough funding to enable them to prioritise their new responsibilities.

In particular, there is large scale underpayment of holiday pay. The TUC estimates that UK workers are missing out on £3.1 billion of holiday pay every year, which is considerably more than estimated underpayment of the National Minimum Wage.

The TUC supports the extension of the remit of HM Revenue and Customs’ minimum wage team to cover enforcement of contractual and statutory holiday pay and statutory sick pay.

Much insecure work is created because organisations outsource functions to others.

It has been proposed that a system of joint responsibility is put in place. This would allow enforcement agencies to contact the organisation at the top of the supply chain to resolve labour rights abuses throughout the supply chain. Failure to do so within a given timeframe would then result in sanctions for the supplier, but the end user would also be named.

The TUC has called for a full system of joint and several liability where the end user would be liable for abuses throughout the supply chain.

A decent floor of rights

We need to ensure all working people benefit from the same floor of decent employment rights from their first day in work and employers cannot contract out of their employment responsibilities.

This would mean a wider range of people would benefit from rights, including the right to request flexible working, to return to their job after maternity and paternity leave, to statutory redundancy pay and for union reps to have paid time off for trade union duties.

Government has proposed legislating to extend from one week to four weeks the break permitted before continuous service ends.

This would allow more people in insecure work to retain rights to things like maternity leave, flexible working, statutory redundancy pay and protection from unfair dismissal.

While any extension of this right is welcome, the TUC argued that all workers should be entitled to key rights from day one. Also, any calendar month during which an individual has done work for an employer should count to continuous service; a ‘ratchet’ effect should apply, so that the period of continuous service does not return to zero after a break. Any periods of statutory leave should count towards workers’ continuous service.

But for these rights to be of value, workers must be able to enforce them, notably through employment tribunals.

In 2017, the government’s employment tribunal fees model was found to be unlawful. Fees were subsequently abolished, enabling more workers to take cases to ensure they are paid properly, including for holidays.

But the system is underfunded and creaking, causing huge delays in resolving cases. And the government has threatened to impose fees again.

We need an employment tribunals system that is properly resourced and accessible to all who need to use it.

New rights so that workers can be protected by a union in every workplace, and new rights for workers to bargain through unions

There is a clear link between the role of trade unions and decent work.

The OECD, a group of developed countries that has been relatively hostile to unions in the past, recently acknowledged that collective bargaining, in which unions and employers negotiate over pay and conditions, tackles inequality:

“Collective bargaining institutions and social dialogue can help promote a broad sharing of productivity gains, including with those at the bottom of the job ladder, provide voice to workers and endow employers and employees with a tool for addressing common challenges.”

But rather than enhance the role of trade unions, instead in the UK we have seen attacks and restrictions on trade union rights.

The Trade Union Act 2016 limits further unions’ ability to organise by imposing arbitrary thresholds in industrial action ballots, adding complicated new balloting and notice rules and placing new restrictions on union campaigning.

Unions have had some notable successes in recruiting members and gaining recognition in workplaces with significant insecure work.

The GMB has signed a collective bargaining deal with delivery company Hermes, for example.

But unions have found it hard to organise in many workplaces without a history of trade union involvement in the face of often transient workforces, hostile employers and restrictive legislation.

The Trade Union Act needs to be repealed. In its place should come a new settlement that allows trade unions to recruit and negotiate effectively in workplaces and across sectors.

Millions of workers and their families face uncertainty, stress and poverty due to insecure work.

Tackling this must sit at the top of the incoming Prime Minister’s to-do list.

But it can’t be done without a commitment to trade union involvement in the workplace and beyond.

And commitment to a robust set of individual, enforceable employment rights that ensures bad employers cannot get away with poor behaviour.

Key Workplace Right |

Who gets it? |

|

Pay |

|

|

National Minimum Wage |

All workers including employees |

|

Holiday pay |

All workers including employees |

|

Family friendly rights |

|

|

Rights to statutory maternity, adoption, paternity and shared parental leave (including to return to their job) |

Employees only with six months’ service by the 15th week before the expected week of childbirth or adoption date |

|

Right to request flexible working |

Employees only after a six-month qualifying period |

|

Unpaid parental leave |

Employees only after a one-year qualifying period |

|

Job security |

|

|

Protection against unfair dismissal |

Employees only following a two-year qualifying period |

|

Statutory redundancy pay |

Employees only following a two-year qualifying period |

|

Rights to representation and consultation (employees and workers only) |

|

|

Protection from unlawful dismissal on grounds of trade union membership or activities |

Employees only |

|

Protection from unfair dismissal for participating in lawful industrial action |

Employees only |

|

Rights to paid time off for union duties or training including for Union Learning Reps |

Employees only |

|

Social security protections |

|

|

Right to be automatically enrolled into a pension by your employer |

Employees and workers who earn over £192 a week |

|

Statutory maternity pay (those who do not qualify may qualify for Maternity Allowance), statutory adoption pay or statutory paternity pay |

Employees and workers who earn £118 or more a week |

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox