Insecure work in 2023

Government inaction has allowed the unchecked growth of insecure work. TUC analysis of official figures shows that by the end of 2022 there were around 3.9 million people in insecure employment.

Huge swathes of the workforce suffer from the effects of insecure employment. For example:

- Zero hours contract workers have great uncertainty over their working hours meaning they often don’t know when their next shift will be or if they will be able to pay their bills.

- Agency workers are being forced to use payroll companies that make unfair deductions from their hard-earned wages.

- Seasonal workers, brought to the UK to carry out key jobs such as picking the fruit and vegetables that are found in our supermarkets, are exposed to staggering exploitation, being charged recruitment fees resulting in debt bondage which often leaves them poorer than before they arrived in the UK.

- Many self-employed workers don’t benefit from basic workplace rights such as parental leave and struggle financially, with 1.88m self-employed workers earning less than 2/3rds of the median wage (£9.72).

Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers are disproportionately affected by the growth of insecure work. Since 2011, the proportion of the working population in insecure work grew from 10.7 per cent to 11.8 per cent. BME workers have borne the brunt of this increase. In the last 11 years the proportion of BME workers in insecure employment has risen from 12.2 per cent to 17.8 per cent.

Despite government promises 1 to introduce “measures to protect those in low-paid work and the gig economy”, and to bring forward an employment bill that would “protect and enhance workers’ rights as the UK leaves the EU, making Britain the best place in the world to work” the government has done nothing to give workers greater security.

Instead, the government has attacked trade union rights by passing the pernicious Strikes Act which undermines the fundamental right to strike for many workers.

We need a new approach that restores power to workers to negotiate secure, decent work for those in insecure employment.

- 1 Rankin, J. (9 December 2021). “Brexit would be better for UK workers, Boris Johnson promised. But will it?”. The Guardian.

Introduction

The TUC brings together more than 5.5 million working people who belong to our 48 member unions. We support trade unions to grow and thrive, and we stand up for everyone who works for a living. Every day, we campaign for more and better jobs, and a more equal, more prosperous country.

Trade unions have led the campaign against insecure work by negotiating agreements which:

- transition insecure workers into permanent employment

- make sure insecure workers can benefit from key employment protections that they would otherwise miss out on.

Unions have secured collective agreements at platform operators, such as Uber and Deliveroo, to raise the floor of conditions. And they have successfully ensured that outsourced public contracts that impose insecure working conditions work have been brought back in-house.

But legislative change is needed to ensure that all people can experience decent work. In the face of government inaction the number of people experiencing insecure work remains stubbornly high.

How many people are affected by insecure employment?

TUC analysis of labour market data shows that 3.9 million people are in insecure work. This amounts to around one in nine of the workforce.

Who is affected by insecure employment?

When estimating the number of people in insecure work the TUC includes:

- those on zero-hours contracts

- agency, casual and seasonal workers (but not those on fixed–term contracts)

- the low-paid self-employed who miss out on key rights and protections that come with being an employee and cannot afford to provide a safety net for when they are unable to work.

Insecure work disproportionately affects groups of workers who are already discriminated against in the workplace.

- TUC research shows that one in six (17.8 per cent) BME workers are likely to be in insecure work. This compares to 10.8 per cent of white workers..

- Analysis from the Work Foundation estimates that 27 per cent of disabled workers (1.3 million) are in severely insecure work in the UK, compared to 19 per cent of non-disabled workers. 2 This inequality is reflected at all levels, with even disabled workers in the most senior positions more likely to experience severely insecure work.

- New research by the Work Foundation and UNISON 3 shows that women in insecure jobs are significantly more likely than men in insecure jobs to indicate they are struggling to get by. Nearly one in three women (32 per cent) say they are struggling to get by compared to less than one in four men (23 per cent). Insecure work appears to disproportionately impact the mental health of women – 16 per cent of women in insecure jobs say they experienced poor mental health, compared to 11 per cent of men. This compares with 10 per cent for men and 11 per cent for women in secure jobs.

How does insecure employment affect working people?

Insecure work has an enormous effect on workers.

Insecure work is low paid in comparison to permanent employment leaving many insecure workers struggling financially. Insecurity and low pay go hand-in-hand. TUC analysis shows that all categories of insecure worker are paid significantly less than employees in general. So not only are many insecure workers vulnerable to the sudden withdrawal of work, but they also have less capacity to withstand shocks to their income because their wages do not allow them to build a savings buffer.

The prospect of having work offered or cancelled at short notice makes it hard to budget household bills or plan wider life. Insecure workers have also reported that have uncertainty around their income makes it difficult to access financial services such as mortgages and loans.

What needs to happen? TUC action plan for the government.

Successive Conservative governments have failed to honour promises to improve working conditions and reduce insecurity at work:

- The government commissioned the Taylor Review on modern working practices which reported in 2017 – but has failed to implement most of its recommendations.

- On dozens of occasions after the 2019 General Election, ministers promised an employment bill to help those on exploitative zero hours contracts. With no action in the 2022 Queen’s Speech, they now appear to have abandoned this commitment.

Instead of focusing on tackling insecure work, ministers have launched a succession of attacks on trade unions, culminating in the pernicious Strikes Act which undermines the fundamental right to strike for many workers.

There needs to be a rebalancing of rights in the workplace so that those in insecure work can secure the decent pay and conditions that they need. As a start this should include:

- Ending the abusive use of exploitative zero-hours contracts

- Introducing fair pay agreements to raise the floor of pay and conditions in sectors with insecure work.

- Establish a comprehensive ethnicity monitoring system covering mandatory ethnicity pay-gap reporting, recruitment, retention, promotion, pay and grading, access to training, performance management and discipline and grievance procedures.

Our full list of recommendations can be found in the final section of this report.

Section 1 - How many people are affected by insecure work?

Insecure work is widespread.

TUC analysis of official figures shows that by the end of 2022, 3.9 million people were in insecure work, this is around one in nine workers (see TABLE 1).

When estimating the number of people in insecure work the TUC includes:

- Those on zero- hours contracts who risk missing out on access to key rights and protections at work, lack income security and face lower rates of pay.

- Agency, casual and seasonal workers (but not those on fixed – term contracts) who risk missing out on key workplace rights and protections and face lower rates of pay.

- The low paid self-employed (defined as those who earn less than two thirds of the median wage, £9.72 per hour). This group miss out on key rights and protections that come with being an employee and cannot afford to provide a safety net for when they are unable to work.

TABLE 1

|

Numbers in insecure work 4 |

|

|

Zero-hours contract workers (excluding the self-employed and those falling in the categories below.) |

1.04m |

|

Other insecure work - including agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed term contracts. |

960,300 |

|

Low-paid self-employed (defined as those who earn less than two thirds of the median wage, which equates to £9.72 per hour). |

1.88m |

|

TUC estimate of insecure work |

3.9m |

|

Proportion of working people in insecure work |

11.8% |

Source – TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

Insecure work is not new, its prevalence has increased since 2010 under the Coalition and then Conservative governments. In 2011, 3.2 million were in insecure work by 2022 the number was 3.9 million, growth of over 700,000.

The proportion of those in insecure work grew from 10.7% to 11.8% between 2011 and 2022. This growth in insecure work is disproportionate compared to wider employment growth over this period. Insecure work increased by 23 percent and the employment level of all those in work by 12 percent - this is almost double.

Section 2 - Who is affected by insecure employment?

BME workers

BME workers face systemic disadvantage and discrimination in the labour market, whether it be lower employment rates and higher unemployment rates, lower pay, more insecure work, or occupational segregation.

Our analysis of the latest data (see TABLE 2) shows one in six (17.8%) of Black and ethnic minority (BME) workers are in insecure work. This compares to one in 10 (10.8%) of white workers.

This inequality has deepened since 2011. Of the growth of over 700,000 in insecure work since 2011, the majority (two thirds) of the increase has been among BME workers. This means the number of BME workers in insecure work has more than doubled in this period.

Since 2011, the proportion of white workers in insecure work increased by 0.3 percentage points compared to an increase of 5.6 percentage points for BME workers.

TABLE 2 - Proportion of people in work (aged 16 and over) who are in insecure work by ethnicity – 2011 to 2022

|

|

White |

BME |

|

2011 |

10.5% |

12.2% |

|

2022 |

10.8% |

17.8% |

|

Change in proportion (percentage point) |

0.3 |

5.6 |

Source – TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

The disproportionate rise can also be clearly seen by looking at the numbers behind the proportions.

TABLE 3 - Number of workers aged 16 and over in insecure work by ethnicity – 2011 to 20225

|

|

White |

BME |

ALL |

|

|

2011 |

2,787,300 |

360,200 |

3,157,700 |

|

|

2022 |

3,052,000 |

836,300 |

3,879,900 |

|

|

Change (number of workers) |

264,700 |

476,100 |

722,200 |

Source – TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

The increase in insecure BME workers has been amongst both men and women (see TABLE 4), though the percentage point increase is slightly larger for BME men, 6.2 compared to 5.1 for women.

An astonishing one in five (19.6%) of BME men are now in insecure work.

For white men the proportion fell slightly over the period.

TABLE 4 – Proportion of workers aged 16 and over in insecure work by ethnicity and gender – 2011 to 2022

|

|

White men |

White women |

BME men |

BME women |

|

2011 |

11.8% |

9.1% |

13.4% |

10.6% |

|

2022 |

11.7% |

9.9% |

19.6% |

15.7% |

|

Percentage point change |

-0.1 |

0.8 |

6.2 |

5.1 |

Source – TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

Over this period our analysis shows BME employment increased by 1.7m, and the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show the employment rate for BME workers (16-64) has increased by 10 percentage points, double the rate experienced by white workers.

However, our analysis establishes that of the increase in BME employment since 2011, 27.3 percent of the net increase is in insecure work. In comparison of the increase in white employment, 15.5 percent of the net increase is in insecure work. And for BME men, of the increase in employment around a third (31.6 percent) is in insecure work.

TABLE 5 – Total increase in workers aged 16 and over in insecure work and total increase in all workers aged 16 and over in employment - 2011- 2022 ( Ethnicity and Gender )

|

|

White Men |

White Women |

White All |

BME Men |

BME Women |

BME ALL |

|

Increase in insecure work since 2011 |

60,600 |

204,100 |

264,700 |

270,800 |

205,400 |

476,200 |

|

Increase in employment since 2011 |

651,000 |

1,055,200 |

1,706,200 |

856,200 |

886,700 |

1,742,900 |

|

Proportion of increase in employment that is in insecure employment |

9.3% |

19.3% |

15.5% |

31.6% |

23.2% |

27.3% |

Source – TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

TUC analysis shows a third of BME male workers are in self-employed delivery and driving jobs, this is an increase of around 80 percent since 2011 from 72,900 to 131, 500.6

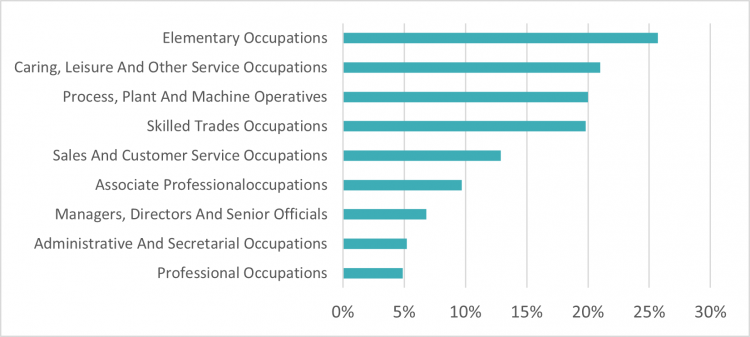

Insecure work is not evenly distributed, it is skewed to lower paying industries - process, plant and machinery operatives; caring and leisure; and elementary occupations.

BME workers in the labour market are overrepresented in these sectors. Occupational segregation plays a significant role in the systemic disadvantage faced by BME workers in the labour market.

So, while the last decade has seen increases in BME employment levels/rates, and falls in inactivity and unemployment rates, there is not only still much to do on improving the chances of BME people being in work, but on improving the quality of work too. As BME workers have borne the brunt of the increase in insecure employment and are at far higher risk than white workers of being in insecure jobs.

There are several reasons why certain groups of workers are over-represented when looking at the data around insecure work.

Structural racism – wider political and social practices that disadvantage BME workers – is prevalent in the workplace. There is often an unequal relationship between employers and workers with BME workers less likely to have bargaining power at work. This systemic inequality and unequal power dynamic plays an important role in explaining why BME people are more likely to be stuck in low-paid, non-permanent, and low-hour jobs.

BME workers are more likely to experience:

- discrimination, for example in recruitment processes

- lack of opportunities at all stages, including training and development

- typecasting and stereotyping into specific roles, often with less favourable terms and pay.

Structural racism plays a significant role in explaining why BME workers are more likely to be in insecure work.

This section has focused on ethnicity as the increase in insecure work has been disproportionate for BME workers.

The following sections look at insecure work by gender, occupation and region.

Gender and Insecure work

In 2011, working men were more likely to be in insecure work, 12 per cent compared to 9.3 per cent for women. When looking at the increase in insecure work to 2022, while men are still more likely to be in insecure work, the increase was for more significant for women – increasing by 1.5 percentage points compared to 0.8 percentage points for men.

Proportion in adults in work aged 16 and over in insecure work by gender 2011 to 2022

|

|

Men |

Women |

|

2011 |

12 % |

9.3 % |

|

2022 |

12.9 % |

10.7% |

|

Change in proportion (percentage point) |

0.8 |

1.5 |

Source – TUC analysis of Labour Force Survey and Family Resources Survey

Recent research from the Work Foundation and UNISON highlights the impact of insecure employment on women.7 Women in insecure jobs are significantly more likely than men in insecure jobs to indicate they are struggling to get by. Nearly one in three women (32 per cent) say they are struggling to get by compared to less than one in fomen (23 per cent). Insecure work appears to disproportionately impact the mental health of women – 16 per cent of women in insecure jobs say they experienced poor mental health, compared to 11 per cent of men. This compares with 10 per cent for men and 11 per cent for women in secure jobs.

Geographical region and insecure work

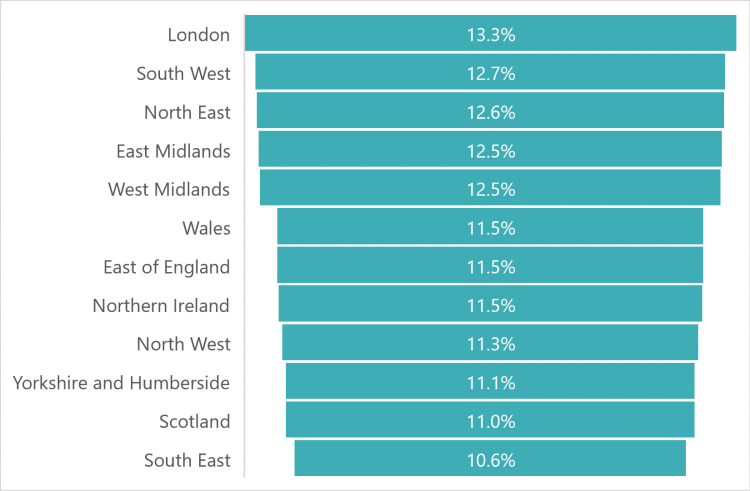

Insecure work is widespread in all regions and nations of the UK.

London (13.3 per cent) and the South West (12.7 per cent) have the highest proportion of people in work in insecure jobs.

Proportion in insecure work by region 2022

- 2 Navani, A; Florisson, R; Wilkes, M. (June 2023). The disability gap: Insecure work in the UK. The Work Foundation.

- 3 Gable, O; Florisson, R. (July 2023). Limiting choices: whypeople risk insecure work. The Work Foundation (Research partner: UNISON).

- 4

[1] The total number in ‘insecure work’ includes

(1) agency, casual, seasonal and other workers, but not those on fixed – term contracts

(2) workers whose primary job is a zero-hours contract

To note - data on temporary workers and zero-hour workers is taken from the Labour Force Survey. Double counting has been excluded.(3) self-employed workers who are paid below 66% of median earnings – defined as low pay.

The data on the low paid self-employed is from the Family Resources Survey 2021/22 and commissioned by the TUC from Landman Economics. The Family Resources Survey suggests that fewer people are self-employed than the Labour Force Survey. And the data from the Family Resources survey looks at from age 18+. (this data is rounded to nearest 10,000)

This year the methodology for insecure work is slightly different to previous years – the data is consistent from 2011 to 2022. For 2011 the low paid self employment data we use is from the Family Resources Survey 2010/11 and use the median pay for that year to work out low pay.

- 5 Minor differences between the total number in insecure work given above and the total number here are caused by rounding

- 6 Looking at insecure work and occupation over time, it is difficult to make a direct comparison in some occupations as the coding for the occupations between the two periods have changed. Though the coding change was mainly in managerial, senior officials, professional occupations, and associate professional occupations. - https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/classificationsandstandards/standardoccupationalclassificationsoc/soc2020/soc2020volume1structureanddescriptionsofunitgroups#summary-of-the-changes-to-the-classification-structure-introduced-in-soc-2020

- 7 Ibid. 3

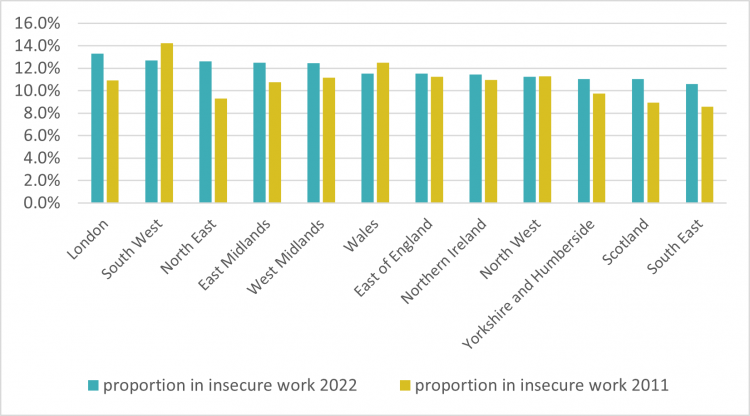

Over the period 2011 to 2022, the North East had seen the largest increase in the proportion of working adults in insecure work, of 3.3 percentage points. However, the proportion of all people there in insecure work remains just under the London rate, at 12.6 percent.

There was an almost 50,000 increase in the number of insecure workers in the North East, from 106,000 to 152,000 between 2011 and 2022.

Proportion of adults aged 16 and over in insecure work by region in 2011 and 2022

Occupation and insecure work

Insecure work is not evenly distributed, it is skewed to lower paying industries - process, plant and machinery operatives; caring and leisure; and elementary occupations.

Proportion of adults in work aged 16 and over in insecure work by occupation , 2022

Low paid work is increasingly insecure, our analysis shows in 2011 one in eight low paid jobs were in insecure work and in 2022 one in five low paid jobs were insecure.

Lack of flexible working arrangements leads to people taking up insecure employment

Genuine flexible working can be a win-win arrangement for both workers and employers. It can allow people to balance their work and home lives, is important in promoting equality at work and can lead to improved recruitment and retention of workers for employers.

But the rise in insecure work demonstrates a rise in employer-sided flexibility, whilst access to flexible working that benefits both working people and employers remains harder to access.

Low levels of flexibility are in large part due to the individualised nature of the law based in a right to request with employers being able to reject requests with ease. TUC research in 2019 showed that three in 10 flexible working requests were turned down.8 TUC polling of dads and partners entitled to paternity leave this year found that 50 per cent did not get any or all of the flexibility they asked for at work.9 This lack of access to decent flexible work is a reason that some workers turn to insecure employment as this is the only way they can manage their work hours alongside their other commitments. 14 per cent of workers on a zero-hour contract polled by the TUC in 2021 said the flexibility to care for children or other people was the reason they worked a ZHC and we know anecdotally from teaching and healthcare unions that a lack of flexibility is pushing them out of the profession into supply or agency work with worse terms and conditions.10

Good jobs should allow for the ability to care for children, older relatives, partners and others as well as receiving good terms and conditions and guaranteed hours associated with secure employment. Two-thirds (66 per cent) of zero-hours workers would rather have a contract with guaranteed hours.11

Workers should not have to turn to insecure employment to manage their non-work commitments. It is possible for decent, secure jobs to deliver flexible working arrangements which benefit both worker and employer, rather than the one-sided flexibility we see with insecure employment. Therefore improving the accessibility to flexible work is vital.

Disabled workers

The Work Foundation’s UK Insecure Work Index 2022 found that disabled workers are more likely to end up in insecure work than non-disabled people. 12

Its analysis found that disabled workers are 1.5 times more likely than non-disabled workers to be in severely insecure work. As of April-June 2022, one in four disabled workers were in severely insecure work (1.3 million). The Work Foundation defines severely insecure work as “Workers experiencing involuntary part-time and involuntary temporary forms of work, or a combination of two or more heavily weighted forms of insecurity”. Whilst this definition differs from the TUC analysis above, the underlying point remains – disabled workers are disproportionately negatively impacted by insecure employment.

Amongst disabled workers, insecure work disproportionately affects groups of disabled workers already facing structural disadvantages in the labour market. Their analysis has found that:

- disabled women face a dual disadvantage and are approximately 2.2 times more likely to be in severely insecure work than disabled men;

- disabled workers from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to be in severely insecure work relative to white disabled workers (29 per cent versus 26 per cent);

- one in three autistic workers (38 per cent) and a quarter of people with mental health conditions (28 per cent) are in severely insecure work compared to 20 per cent with other disabilities and conditions.

The Work Foundation reports that disabled workers are more likely to be in routine and semi-routine occupations such as cashiers, bricklayers and waiters, and are less likely to be in professional and managerial work relative to non-disabled workers. This is concerning because access to flexible working arrangements – such as flexible hours or remote working – can be particularly valuable for disabled people and is much less common in routine occupations.

Section 3 - How does insecure employment affect working people?

Low pay and poverty

Insecure workers face a pay penalty. Low pay is a contributory factor to many insecure workers facing poverty.

TUC analysis shows the median gross hourly pay for those in casual work in 2022 amounted to £6.80 an hour in 2022,13 for seasonal work £9.80 and for zero hours workers £9.40. Those working for an employment agency typically received £11.50. But this is well behind the median for all employees which was just above £14.14

Recent analysis from Trussell Trust found that just under a third (30 per cent) of people in paid work referred to Trussell Trust food banks are in insecure work, for example, zero hours contracts or agency work.15

BME people are also more likely to be in poverty than the white British population. The major cause of this poverty is the multiple forms of racism BME workers face.

Uncertainty of hours

Previous polling for the TUC has shown that employers are increasingly likely to offer shifts at short notice to workers on zero-hours contracts. In 2021, research for the TUC 16 found that:

- 84 per cent of these workers have been offered shifts at less than 24 hours notice

- more than two-thirds of zero hours contracts workers (69 per cent) had had work cancelled at less than 24 hours notice

- most zero hours workers only took on this type of contract because it was the only work available.

This is disruptive and makes it more difficult for insecure workers to balance their work and private life commitments.

Restricted access to financial services

Workers have previously reported to the TUC that they could not build up a credit history to secure mortgages or loans.17

Insecure workers miss out on key employment protections/rights

Often those in insecure work miss out on key workplace rights such as:

- the right to return to the same job after maternity, adoption, paternity or shared parental leave

- the right to request flexible working

- the right to protection from unfair dismissal or statutory redundancy pay

- and many insecure workers miss out on key social security rights such as statutory sick pay, full maternity pay and paternity pay.

Lack of access to training and development

Progression is also a problem as employers fail to invest in those they feel they have little obligation to. Non-standard employment often means that you receive little training and development, according to the OECD.18

Lack of flexibility

Many insecure workers report that insecure work does not give them the genuine flexibility they need to manage their commitments outside of work.

The reality of insecure work can mean effectively being on call and having to accept shifts at short notice or being fearful to ask for different working patterns due to risk of losing shift work in the future. Because of the pay penalty associated with insecure work many workers will also have to work long hours, meaning flexible work is not an option. The right to request flexible working is also only available to employees not worker.

TUC research revealed that zero-hour contracts do not offer the flexibility to manage other commitments employers claim they do. Less than half (45 per cent) of insecure workers say they have the right in their current job to request a change to their regular working hours to fit around other commitments.

Imbalance of power in the employment relationship

Insecure work also further distorts power in the workplace. If you are reliant on the whims of a boss for your next shift you are far less likely to complain about conditions, let alone ask for a pay rise.

Section 4 - What needs to happen? TUC action plan for the government.

There is an urgent need to challenge insecure work and to introduce a framework of policies designed to encourage the creation of decent jobs, offering decent hours and pay. Failure to do so will result in further entrenchment of racial inequality in the labour market.

The government policy on race relations and employment has mainly aimed at creating good practice in the public sector on the premise that this will filter through to the private sector. This is a false premise - if race equality in employment is to be achieved then discriminatory practice in the private sector which makes up over 80 per cent of the workforce of Britain, must be tackled directly.

To create decent work and to tackle the increasing exploitation and exclusion from employment rights faced disproportionately by BME workers there needs to be concerted and co-ordinated government action to tackle insecure work and tackle racial discrimination in the labour market.

Below we set out an action plan for the government to address insecure work and ensure that marginalised groups do not disproportionately suffer the negative impacts of insecure employment.

- Introduce race equality requirements into public sector contracts for the supply of goods and services, to incentivise companies to improve their race equality policies and practices, minimise the use of zero-hours, temporary and agency contracts, and promote permanent employment. Companies that do not meet the requirements should not be awarded a public contract.

- Ban the abusive use of exploitative zero-hours contracts, by giving workers the right to a contract reflecting their normal hours of work and ensure all workers receive adequate notice of shifts, and compensation when shifts are cancelled at short notice.

- Reform the rules on employment status to ensure that all workers benefit from the same employment rights, including statutory redundancy pay, protection from unfair dismissal, family-friendly rights, sick pay and rights to flexible working. To this end, employment status law should be modernised, putting an end to the current two-tier workforce.

- Introduce legislative measures to repeal the Strikes Act and other anti-trade union legislation and to stimulate collective bargaining and make it easier for unions to speak with and represent insecure workers. To increase collective bargaining our proposals for reform include:

- Unions to have access to workplaces to tell workers about the benefits of union membership and collective bargaining (following the system in place in New Zealand).

- New rights to make it easier for working people to negotiate collectively with their employer, including simplifying the process that workers must follow to have their union recognised by their employer for collective bargaining and enabling unions to scale up bargaining rights in large, multi-site organisations.

- Broadening the scope of collective bargaining rights to include all pay and conditions, including the use of atypical employment, pay and pensions, working time and holidays, equality issues (including maternity and paternity rights), health and safety, grievance and disciplinary processes, training and development, work organisation, including the introduction of new technologies, and the nature and level of staffing. The establishment of new bodies for unions and employers to negotiate across sectors, starting with social care.

These measures would enable unions to speak with and represent insecure workers. Legislation that facilities negotiations between unions and employers would lead to a reduction in the use of insecure employment.

- Work with trade unions to establish a comprehensive ethnicity monitoring system covering mandatory ethnicity pay-gap reporting, recruitment, retention, promotion, pay and grading, access to training, performance management and discipline and grievance procedures. The TUC believes that in order to ensure employers effectively address the issues that they have identified in their analysis of pay and other data, they should follow up with an action plan and narrative. Employers should set aspirational targets to close the pay gap and publish, report on and review these on a regular basis. Actions to eliminate ethnicity pay gaps might include minimising or eliminating the use of insecure employment where BME workers are disproportionately overrepresented.

- Act to address the under-representation of young BME workers on apprenticeships and ensure that young black women are able to access the full range of apprenticeships and do not suffer labour market segmentation in relation to access to training on the basis of their gender.

- Crack down on bogus self-employment, which is one of the key drivers of insecure employment, by introducing a statutory presumption that all individuals will qualify for employment rights unless the employer can demonstrate that they are genuinely self-employed.

- Create a legal duty on employers to consider which flexible working arrangements are available in a role and publish these in job advertisements, with the new postholder having a day one right to take up the flexible working arrangements that have been advertised. If an employer does not think that any flexible working arrangements are possible, they should be required to set out that no form of flexible working is suitable in the job advert and why.

All roles should be deemed suitable for flexible working unless it can be shown that the unavailability of flexible working is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. Flexible working legislation would reflect objective justification as set out in the Equality Act 2010.

And create a day one right to request flexible working for all workers, with the criteria for rejection mirroring the objective justification set out above. Workers should have a right to appeal and no restrictions on the number of flexible working requests made.

- 8 (September 2019). “One in three flexible working requests turned down, TUC poll reveals”.

- 9 Oppenheim, M. (July 2023). “‘Overwhelmingly frustrating’: Half of new fathers have requests for flexible working denied, study finds”. The Independent.

- 10 Representative online survey of working Britain: adults 16+ who are in full- or part-time employment, weighted to national statistics on gender, age, region, social grade, ethnicity, work status, sector, and experience of furlough:

- Total sample n=2523, including oversamples of BAME workers and people on Zero-Hours Contracts (ZHCs)

- 20-minute questionnaire

- Fieldwork: 29th January – 16th February 2021

- 11 (December 2017). “Two-thirds of zero-hours workers want jobs with guaranteed hours, TUC polling reveals”. TUC website.

- 12 Ibid (List number from above)

- 13 60% of casual workers are aged under 23 and are entitled to a lower NMW rate than over 23s, which explains the low £6.80 hourly wage for casual workers.

- 14 TUC analysis of labour force survey

- 15 Trusell Trust 2023 ‘ Hunger in the UK’- https://www.trusselltrust.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/06/2023-H…

- 16 TUC (2021). Jobs and recovery monitor - Insecure work, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/researchanalysis/reports/jobs-and-recovery-monitor-insec…

- 17“Living on the Edge - Experiencing workplace insecurity in the UK”. TUC.

- 18 OECD (2017). Economic Surveys: United Kingdom 2017, www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/eco_surveys-gbr2017-en/1/2/1/index.html?ite…- en&_csp_=af42fd060842c10b19dd161a0d87fa81&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book#sec1-00001

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox