Impact of Covid-19 and Brexit for the UK economy

This brief sets out key themes from some of the recent analysis to emerge on both the impact the changing nature of the UK’s trading relationship with the EU and the rest of the world from January 1st 2021 and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The UK’s deal with the EU seems likely to be a ‘thin’ trade deal and will not be the smooth transition that many had hoped for. Some of the impacts such as customs and border disruption will be front loaded whereas others may materialise in the longer term as the UK diverges from the EU on things such as product standards or other regulations.

The Covid-19 crisis and its economic impact will also have profound structural effects on the UK economy and labour market as the crisis continues to speed up existing trends such as the move to more online shopping, whilst seeing growth in newer trends such as more people working from home.

The nature of both are likely to lead to a long and protracted restructuring of the UK economy, the impact of which will be felt for many years to come.

Recent analysis suggests that:

- in most cases it is likely that that the regions and sectors most affected by the economic impact of Covid-19 are not the same as the regions and sectors likely to be most exposed to Brexit (though there are some exceptions), but that both crises combined will have a broader impact on the UK than either would have done in isolation.

- Manufacture of automotive, transport equipment, chemicals and chemical products and textiles, and services such as finance and communications are the most exposed sectors to Brexit. Hospitality, tourism, transport and arts and entertainment are the most exposed sectors in relation to economic impact of Covid-19. The automotive industry is one of the sectors that has experienced a downturn due to Covid-19 and is likely to be significantly impacted by Brexit.

- Both the economic impacts of the coronavirus and the impact of Brexit are likely to increase regional disparities. London, the North East, Wales, the South East and the West Midlands are most exposed to Brexit associated risks, whereas tourism dependent coastal communities and hospitality dependent cities such as Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and large parts of London are likely to be most exposed to the short term economic impact of Covid-19. The North West, London, South East and the West Midlands may experience a ‘double whammy’ of both the economic impact of Brexit and Covid-19.

Economic overview

Current economic and labour market situation

The economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic has hit the UK particularly hard in comparison to international counterparts. Latest figures for quarter three (July – Sept) show the UK economy is still 9.7 per cent below its pre pandemic levels, more than double the decline seen in the US and the EU. In quarter two (Apr – June) the UK decline of 20.4 per cent was steepest of all comparable countries and double the OECD average of 9.9 per cent. Over the first half of the year the UK was second worst (to Spain) of all OECD countries.

Further, the most recent monthly GDP figures showed the UK ‘bounce back’ was continuing to slow even before further lockdown restrictions were announced, with monthly growth of only 1.1 per cent into September. Though this is the fifth consecutive month of growth, the pace continues to slow from 9.1 per cent in June, 6.4 per cent July and 2.1 per cent August.

Most recent furlough data from the ONS BICs survey (dated 19th October to 1st November) shows that 9% of the workforce (over 2 million employees) remained on partial or full furlough, and with the extension of lockdown measures and the Job Retention Scheme this number is likely to increase. Latest labour market stats show redundancies hit an all-time high of 314,000 in Jul-Sep 2020. Unemployment increased more this quarter than any other time on record.

The economic outlook

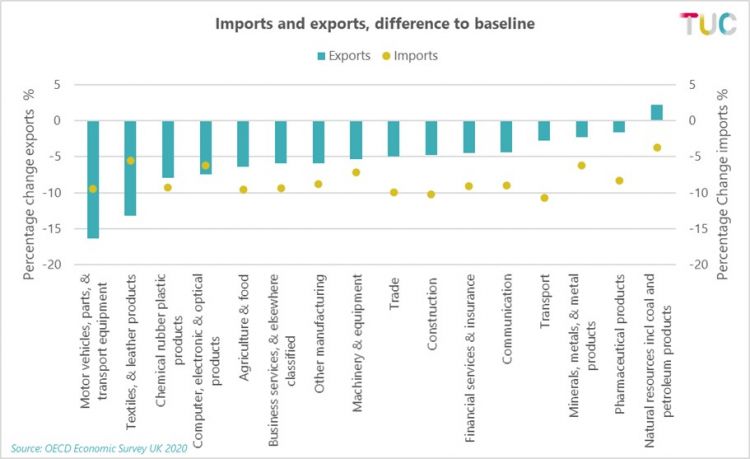

The OECD in its Economic Survey for the UK 2020 expects that the impact of a comprehensive FTA compared to the current trading relationship between the U.K and EU would be a 6.1 per cent fall in exports and a 7.8 per cent fall in imports leading to a 3.5 per cent output loss over the medium term. Ending freedom of movement of EU citizens would hit service industries particularly hard and could result in a further loss of 0.7 per cent in output terms. They note that given the UK has a well-designed regulatory regime for services, some of the loss could be compensated for by speeding up visa deliverance, and reforms to procurement and data flows, however this could be difficult to implement in the short term and its impact on the medium term outlook would still be limited (with an output loss of 3.2 per cent as opposed to 3.5 per cent).

They estimate that the impact on the unemployment rate would be an increase of 1 percentage point on average across all sectors, though some sectors will fare worse than others.

The IFS estimate that the UK economy will be 2.1 per cent smaller in 2021 if the UK were to agree an FTA with the EU versus if the transition period had continued indefinitely. They expect net trade to reduce by 1.5 percentage points in 2021 with exports and imports falling by 7.4 per cent and 7 per cent respectively versus their 2018 levels.

The IFS think much of the cost and disruption of Brexit will be front loaded in 2021, for example due to one off administrative costs to businesses such as reapplying for export licenses and disruption and delays at the borders while the system is worked out. However, they also note that going forward the cost of filling out customs declarations is estimated at an additional £7 billion a year.

Beyond 2021 the IFS estimate output in 2024 will be 4.5-5 per cent lower below the March 2020 OBR forecast, equivalent to an annualised GDP loss of £109 billion. The IFS argue that the majority of this will be because of the permanent reconfiguration of the economy due to Covid-19, accounting for 3-3.5 ppt of the output loss. They attribute the remaining 1-1.5 ppt fall in output to the impact of leaving the single market and customs union, the impact that will have on restructuring certain parts of the economy and the write off of capacity in some sectors.

Both the OECD and IFS estimates are not dissimilar from previous projections from the OBR and Bank of England, which suggested that a hard Brexit could result in a fall in GDP of between 4-5 per cent after two years.

The IFS also note that some of the potential economic benefits of Brexit may have already been felt, for example the depreciation of sterling after the referendum result has helped to make some sectors e.g. food production more competitive and has helped boost profitability and growth in tradable sectors. However, as tariffs and Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) are yet to come into effect, the costs of leaving the single market and customs union have not yet been realised.

Another consideration is that because of the weakness of sterling since 2016, firms may have continued with their business activity even if in the long-term post Brexit, they are unviable. Coupled with the weak investment levels since 2016, there is a risk of sudden divestment and this could have a significant impact on the labour market as firms have hired in lieu of investment which is more easily reversible. As a result of Brexit and Covid-19 the IFS expect unemployment to peak at 8-8.5 per cent in Q2 2021.

The impact of no deal

Our working assumption is that a Free Trade Deal will be reached, however if this is not the case the UK will revert to trading on WTO terms, which is likely to have a longer-lasting negative impact even as FTA’s with other trading partners emerge. As the OBR note:

“both the Government’s own estimates and those of independent experts suggest that gains from all third-country FTAs are together likely to be modest. For example, the Government estimates that substantial mutual tariff liberalisation with the US would increase GDP by between 0.02 and 0.15 per cent in the long run. Such deals are therefore unlikely to compensate for the costs associated with a failure to secure an FTA with our nearest and largest trading partner”.[1]

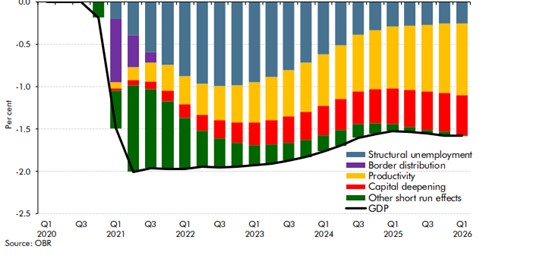

The OBR in its latest Economic and Fiscal Outlook, published in November, finds that reverting to WTO terms after the transition period ends will knock an additional 2 per cent off real GDP versus their central forecast which assumes a ‘typical’ FTA and smooth transition to new arrangements. In comparison, the IFS estimate that no deal could reduce GDP by a further 0.5 – 1 per cent versus reaching an FTA. Similarly, the OECD estimate that ending Freedom of Movement would reduce output by 0.7 per cent over the medium term.

The long-run impact of not reaching a deal and trading on WTO terms would leave output around 1 ½ per cent lower after five years according to the OBR versus their central forecast.

Chart 1: OBR difference in real GDP to central forecast

[1] OBR, Economic and Fiscal Outlook, November 2020, (25/11/2020), http://cdn.obr.uk/CCS1020397650-001_OBR-November2020-EFO-v2-Web-accessible.pdf (p196).

The OBR also note that leaving on WTO terms will slow down the recovery from the pandemic, delaying the point at which output returns to its pre-crisis peak by almost a year to the third quarter of 2023 versus their central forecast.

The OBR estimate unemployment will be 0.9 per cent higher in the third quarter of 2021 at 8.3 per cent versus their central forecast (7.4 per cent) because of no deal. They also expect the impact of tariff and non-tariff barriers and a drop in the exchange rate to leave inflation 1.5 per cent higher by the end of the forecast period versus their central FTA scenario.

As section three highlights, the consensus is that the sectors most impacted by the virus are less exposed to Brexit and vice versa. The OBR reflect this and also note that the non-overlapping sectoral impact suggests that any loss of output associated with trading on WTO terms is likely to be additional to that experienced because of the pandemic.

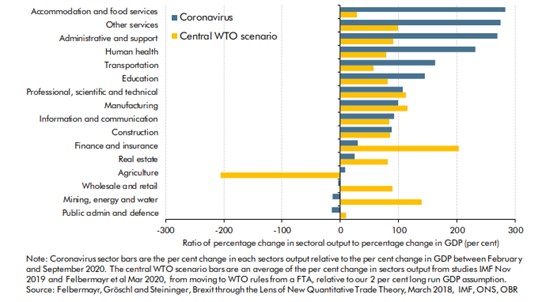

Chart 2: OBR Relative intensity of output hits: virus vs Brexit

Variations in the impact of Brexit and Covid-19

Sectoral impact

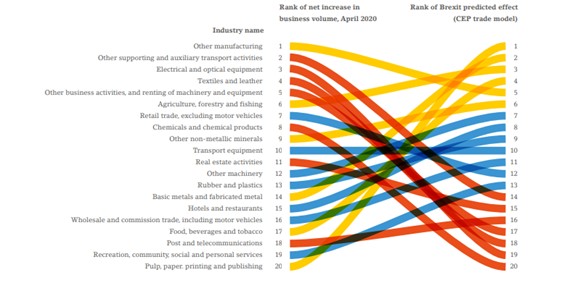

Generally, the sectors that are most exposed to Brexit are less exposed to the economic impact of Covid-19. The table below from the LSE comparative paper below shows changes in business volume in April of this year and the predicted impact of Brexit. Industries are ranked on the left-hand side in terms of their net increase in business volume in April 2020: from least negatively affected (1) to most negatively affected (20). The lines are shaded according to the predicted long-term effect of Brexit (Dhingra et al, 2017): red for most negatively affected; yellow for least negatively affected; and blue in between. For example, Textiles and leather saw less impact in terms of business volume due to Covid-19 (ranked 4 on the left-hand column) but is shaded red as it is likely to be significantly impacted by Brexit.

The LSE suggests chemical and chemical products and textiles, as well as electrical and optical equipment are likely to be some of the most impacted by Brexit but notes significant impacts on other sectors and industries.

Chart 3: LSE change in business volume April – June 2020 and predicted Brexit impact.

The manufacturing sector is considered the most exposed to Brexit due to the increase in tariffs and Non Tariff Barriers and the impact it will have on supply chains which are often deeply integrated with the EU. Though again this varies by manufacturing industry with the OECD expecting motor vehicles and transport equipment, chemical, rubber and plastic products, textiles, and meat to be most affected (see chart 2).

From an employment perspective this means that jobs in certain industries are more exposed than others. For example, the OECD estimates the unemployment rate could rise by 2.4 per cent in the motor vehicle, parts and transport equipment industry.

The automotive industry is one of the sectors that has experienced a downturn due to Covid-19 and is likely to be most impacted by Brexit. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) note that UK car production fell to its lowest level since the second world war, down 99.7 per cent in April 2020 and the new car market fell 43 per cent in the first quarter of 2020.[1]

Based on media announcements so far this year, we estimate that over 11,000 jobs have potentially been lost across the automotive industry (inclusive of automotive retail) since the onset of the pandemic.

Similarly, the Chief Operating Officer of Nissan recently cautioned that any final deal that worsened business conditions through increased tariffs could make their UK operations unsustainable. Signalling Nissan could leave its Sunderland site where it employs 7,000 workers in the event of a bad or no deal, Ashwani Gupta said, “If it happens without any sustainable business case, obviously it is not a question of Sunderland or not Sunderland, obviously our UK business will not be sustainable, that’s it”[2].

The loss of passporting rights and unresolved issues on equivalence and data flows will have an impact across the service sector, with the OECD estimating output losses of between 2 per cent and 7 per cent in the medium term, depending on the service industry. Losses of above 3 per cent are expected in key service industries such as finance, business services, communications, and construction. Though smaller in relative terms, because of the importance of services to the UK economy (services account for around 80 per cent of output and employment) they represent large losses. The LSE also note that professional, financial and communications services are likely to be significantly affected by Brexit.

Chart 4: Imports and exports, differences to baseline

[1] Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) https://www.smmt.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/SMMT-Automotive-Trade-Report-2020.pdf

[2] Kelly, T, Dolan, D. Reuters, 18/11/2020, ‘Nissan’s Britain business tough to sustain without Brexit trade deal – COO Gupta’ https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-britain-eu-nissan-interview/nissans-britain-business-tough-to-sustain-without-brexit-trade-deal-coo-gupta-idUKKBN27Y0GH

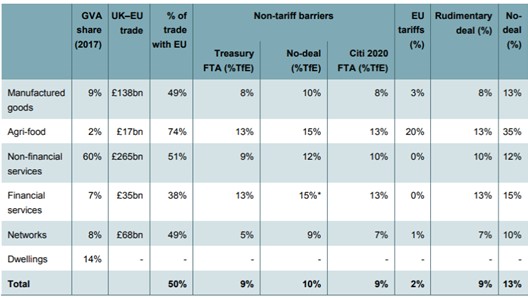

Most increased costs of Brexit are likely to come from NTBs, which even with a Free Trade Agreement would not be eliminated entirely. The IFS finds that additional barriers to trade will have a tariff equivalent cost impact of +9 percent in the event of a deal. In the government’s own 2018 impact assessment, loss of passporting rights and a standard FTA were found to potentially increase trade costs in financial services by 13 per cent.

Table 1: IFS sectoral exposure estimates of Brexit

The impact on services could also further exacerbate the UKs productivity problem, with the OECD estimating a decline in productivity across the service sector of 3-5 per cent in the medium term, with transport and storage; professional, scientific and technical; and financial and insurance services being most affected.

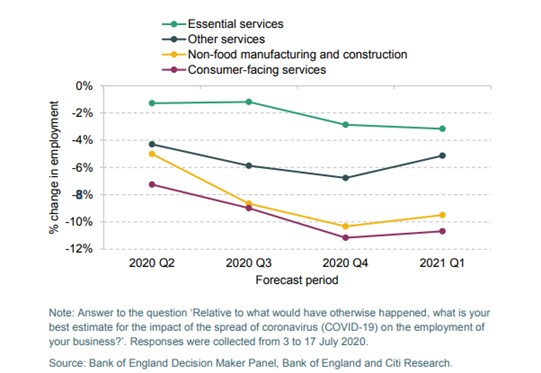

In contrast, sectors that have been most impacted by Covid-19 such accommodation and food, certain types of retail, transport including air travel and arts entertainment and recreation, may not see as much of a direct impact due to Brexit and a new trading relationship. However, one key aspect is that for some sectors such as hospitality (and health and social care) the effect of reduced migration could have a significant impact on the workforce as they rely disproportionately on EU migrants. IFS survey data suggests that all sectors are planning to reduce the size of their workforce due to Covid (see chart below).

Chart 5: IFS estimated impact of covid-19 on workforce size, July 2020

Similarly, increased prices of imports could impact by either reducing demand as consumers have to deal with rising costs of living (13 per cent of the CPI basket of goods is directly imported from the EU and 7 per cent indirectly imported) or by increasing the costs of goods for businesses, such as restaurants and cafes.

Business (and government) preparedness for Brexit is a concern: the OECD cite research suggesting that of June 2020, 61 per cent of British businesses had not made any preparations for leaving the single market. Similarly, the IFS cite the Institute for Directors’ survey which suggests only a quarter of businesses were fully prepared and 45 per cent were fully focussed on the pandemic and planned only to address Brexit when the future relationship with the EU became clearer.

Regional impact

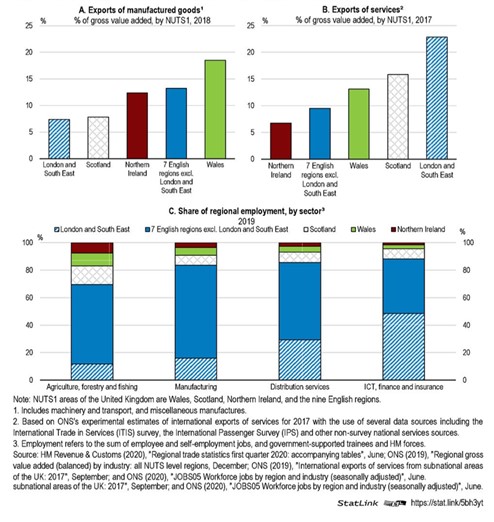

In terms of Brexit, the literature generally shows that North East, the West Midlands, Wales, London and the South East are considered particularly exposed due to their reliance on the EU for exporting of goods or services (for example see OECD chart below).

A recent report from the Social Market Foundation suggests that London, the North West, the South East and the West Midlands are most exposed to a double whammy from the impact of the coronavirus and failure to secure a deal with the EU (and to a lesser but still significant extent by a FTA agreement).[1]

[1] Social Market Foundation, https://www.smf.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Assessing-the-economic-impact-of-coronavirus-and-Brexit.pdf

Chart 6: OECD regional exposure to Brexit

The IFS in their Green Budget paper suggest that Brexit is likely to have a significant impact on particular groups such as blue-collar, male workers, with less formal education qualifications. There is a higher concentration of workers that fall into this group in some of the ‘left behind’ areas such as the Northern regions, South Wales and the West Midlands.

The IFS also suggest that the traditionally ‘left behind areas’ are not those most exposed to the short-term economic impact of Covid-19. However, there are notable exceptions such as large parts of London, tourism dependent coastal communities and hospitality dependent cities that have historically high incidences of deprivation such as Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow.

Other considerations will be the behavioural changes of working from home and the impact if these trends become long term, which could influence areas and businesses that rely on people physically being in offices: this is likely to affect cities and large towns in particular.

Further, the EU funding to regions and nations of the UK through the European Regional Development Fund (EDRF) and the European Social Fund (EFS) have contributed £15 billion over the last 7 years (approx. £1.6 billion annually since 2014). The funding has supported many regional development projects through LEPS and has underpinned many of the recent moves to devolution in Greater Manchester and South Yorkshire. The government has promised to replace this funding with the Shared Prosperity Fund, but thus far few details have been shared about the replacement fund[1]

Conclusions

The literature is clear that there is a high risk that both the economic impacts of the coronavirus and the impact of Brexit are likely to:

- increase regional disparities;

- impact on particular groups such as blue-collar, male workers highly concentrated in some of the ‘left behind’ areas such as the Northern regions, South Wales and the West Midlands;

- affect different sectors and cumulatively have a wider effect on the economy overall.

The policy choices made thus far in the negotiations do not seem to tackle this evidence and it is urgent the government conducts and publishes a new impact assessment to show the effects these choices will have in the short to medium term.

[1] In the November Spending Review, the Chancellor announced £220 million in 2021/22 to support pilot schemes in preparation for the replacement fund and restated commitments to at least match EU receipts. More details are due in the spring. https://www.lgcplus.com/finance/spending-review-220m-for-uk-shared-prosperity-fund-pilots-25-11-2020/

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox