The future of rail funding in the UK

Rail is a major driver of the UK economy. In 2019 the UK rail sector contributed £14.1bn in tax revenue. It provides employment for thousands of workers and enables millions more to travel to and from their place of work. Rail is also a low carbon transport mode. The Future is Public Transport report estimated that doubling public transport usage as part of a green recovery would, by 2030, create tens of millions of jobs in cities around the world (4.6 million new jobs in the nearly 100 C40 cities alone), cut urban transport emissions by more than half, and reduce air pollution from transport by up to 45%.

Rail is crucial to meeting our commitments in tackling climate change, too. According to the International Energy Agency, ambitiously expanding rail could cut 15% of the global transport system’s energy demand by 2050. The investment needed for the shift to low carbon transport outlined in the Paris agreement would generate 143,700 public transport jobs in London alone. While the UK as a whole would gain 161,900 additional jobs, for a total of over 300,000 jobs between 2021 and 2030. The TUC estimates that rail upgrades and electrification, if front-loaded over the next two years as part of emergency economic stimulus, could create 126,000 jobs for two years.

But the government is endangering this with short-sighted and damaging cuts to rail funding. The cuts threaten service levels and safety.

Network Rail began implementing cuts to spending in 2019 and has committed to more in 2021. Transport unions have already raised concerns that these cuts undermine vital maintenance schedules and, ultimately, put lives at risk.

Rather than short-sighted funding cuts, Britain’s rail industry needs fundamental overhaul and investment. The TUC advocates for full public ownership and reuniting oversight of train services with tracks and other infrastructure. This proven approach would put Britain in line with our European peers and the world’s most successful railways. Considering the deep failures of the privatisation era, reflects the broad consensus that public ownership is a necessary precondition for the post-pandemic recovery of the industry and wider national economy.

We have reviewed several alternative models for funding and running a national rail industry and we examine several examples and draw out lessons for the UK.

The franchise model

Between privatisation in the 1990s and the outbreak of Covid in 2020, British railways operated a franchise model. The Department for Transport (DfT) tendered contracts to run individual lines. Train Operating Companies (TOCs) would bid for them based on planned investment and service improvements they could offer. Those companies would then have the right to sell tickets for the services and hold the risk of profit and loss. This was meant to be a competitive process. In fact, there are very few entities with the capacity to bid for a railway franchise, and most of them are subsidiaries of foreign state-owned railway companies. Attempts to create a competitive market for rail transport in Britain have in effect created conditions more like a cartel, extracting value from the UK to support state owned infrastructure abroad.

The result of this system was a highly fragmented rail industry, with multiple actors and often conflicting incentives. Despite their ultimate ownership, the TOCs are all in practice private operators incentivised to run a profit and pay out dividends to their shareholders. The DfT was required to engage in multiple, complex, and expensive tendering processes, and on occasion had to repeat the process when irregularities or legal challenges invalidated an award. The result was a complicated, expensive system where profit and investment continually leaked out rather than going towards improved infrastructure, safety, and affordability.

COVID and the end of franchising

In March of 2020 the pandemic and subsequent lockdown meant passenger numbers collapsed. As a result, the government was required to intervene on a huge scale. The DfT provided TOCs with two tranches of emergency funding (Emergency Rail Measures Agreements, and subsequently Emergency Recovery Measures Agreements) that paid them a flat fee to keep services running regardless of passenger numbers.

The old franchise system had effectively been replaced by a model of state-owned concessions. The TOC’s continue to employ staff and run services, but the responsibility for determining operating parameters (e.g. staffing levels, timetabling, and investment), collecting revenues, and absorbing losses is transferred to the state.

Although public intervention on this scale was desperately needed, it resulted in immense public subsidies to profit making companies. So huge profits leaked out of the industry. The Welsh Government used the option of turning itself into an ‘operator of last resort’ to nationalise Transport For Wales during the height of the pandemic 1 Many of the current operating companies have been taken over by state backed operators of last resort because of service failures and financial irregularities. Operators currently in, or being transferred to, government hands include LNER,2 Northern,3 Southeastern,4 and Scotrail.5

The Williams-Shapps plan

The Williams-Shapps plan was published in 2021. It lays out the structure of the rail industry after the end of the Franchise model that has been in place since privatisation in the 90s. The plan is the result of the Williams Rail Review which was initiated following severe disruptions in 2018.

The results of the Williams Rail Review were repeatedly delayed. Despite this, it had been clear for some time that the report would conclude that the franchise system was not fit for purpose and should be replaced. The broad outline of the replacement had also been heavily hinted prior to publication. The old, fragmented model where TOCs bid for the right to operate different lines as their own businesses would be replaced with a concession model similar to Transport for London (TfL)The right of private companies to bid to run sections of the network would remain in place, but with a much greater level of centralised command and control.

Before the plan could be published however, the Covid-19 pandemic intervened, and the government was forced to step in; a key plank of the Williams’ review had in effect been implemented.

Great British rail

Under the Williams-Shapps plan, a new body will be created that will have responsibility for both the provision of rail services currently carried out by TOCs, and the infrastructure management role currently carried out by Network Rail.

This new entity will be called Great British Rail and it will be capable of overseeing the whole of the British Rail industry. Previously different bodies were responsible for trains and infrastructure.

A missed opportunity

Private operators will continue to receive government funding. This means funds that could be used for vital maintenance, ensuring sufficient staff to run stations safely and effectively, and providing important upgrades to infrastructure, will instead leak out to private profit and dividend payments. A certain level of fragmentation and duplication will continue to be entrenched, as concession holders will necessarily maintain their own administrative and bureaucratic structures.

The model is bad for workers too. Almost every aspect of investment and service provision will be determined by GBR, so one of the only ways that concession holders can compete to run services at a lower cost is by taking measures reduce staff costs by reducing pay and making use of casualised and precarious labour. Entrenching the position of many different employers restricts the scope for sectoral collective bargaining and prevents the standardisation of wages, terms, and job roles at a national level.

Incredibly, and despite the clear need for massive investment to make any reform of the industry viable, the Williams-Shapps plan set out a target of £1.5bn in savings over five years.6 It is in this context that we must consider the planned cuts which the rail industry is facing, and to Network Rail in particular.

At the end of 2021, industry insiders indicated that DfT were pressing operators to deliver swinging cuts amid their attempts to reach 10% savings.7

As well as representing a huge loss of services, cuts like this would mean that remaining services would become more crowded, dissuading many commuters who have the choice of transport options. More crowded trains also represent an increased risk of Covid. At a time when case numbers are once again at record levels, it is unwise to risk the health of commuters and their families. Especially as the industry is working so hard to reassure those who may have doubts about the safety of returning to train travel.

Network Rail

Since 2002 rail infrastructure and management has been the responsibility of Network Rail, a non-governmental, but publicly owned enterprise. Network Rail took over from private operator RailTrack after a series of fatal rail accidents and in particular the Hatfield crash in October 2000 were linked to serious failures of maintenance. In 2014 the immense debts Network Rail inherited from RailTrack were transferred to the government balance sheets, completing the nationalisation process.8

However, in 2019 the Department for Transport (DfT) announced that Network Rail would be required to make “efficiencies” of £3.5bn over the following 5-year funding period. In 2021 it committed to increase planned savings to £4bn over the same period.9 Cutting, rather than expanding, the capacity of Network Rail runs the direct risk of returning to the same failed policies which sunk RailTrack, not to mention costing many hundreds of lives.

Threats to safety

The UK rail sector is considered safe, in fact the 2017 Rail Performance Index rated Great Britain as extremely safe.10 However, the sector was facing damaging and potentially dangerous cuts even before the pandemic slashed passenger revenues.

These cuts threaten essential services and maintenance and increase the risk of the types of accidents that marked the first decades of privatised rail and Network Rail’s planned savings would bring its total Operating Costs down to levels not seen in a decade.

We estimate that to meet its initial efficiency targets of £3.5bn by 2024, Network Rail would have to cut an average £800,000,000 a year from its expenditure. This equates to eight per cent of its core operating cost in 2019/20 and seven per cent in 2020/21. It should be noted that Network Rail committed to even deeper cuts in May of 2021 aiming for £4bn by 2024/25.11 Figures for 2021/22 are not yet available, but in their 2021 update, Network Rail estimated their total expenditure would be £50.3bn over Control Period 6 (2019-2024).12 On that basis their planned cuts would account to 9% of expenditure each year.

Network Rail has already implemented a voluntary severance scheme to which thousands of employees subscribed but is currently consulting with unions on the loss of 2660 maintenance jobs, over a fifth of relevant posts.

Network Rail plan to cut the total hours of Maintenance Scheduled Tasks (MSTs) by 669,000 hours or 34% a year according to RMT analysis of Network Rail data.

In the UK, there are more than 20,000 miles of track, nearly 6,000 level crossings, 30,000 bridges and viaducts and at the last count 2,500 stations. Many of the tunnels, viaducts and bridges were in the 19th century, and so require high levels of maintenance.

These cuts would mean a 34% reduction in maintenance hours. As well as increased disruption and breakdowns, it means greatly increased risk to safety. Railway work is often outdoors, at unsociable hours, and based on strenuous rotating shift patterns. This requires Network Rail to maintain capacity to check and avoid the higher risk of human errors from this working environment. In order to carry out the right level of preventative risk management, staffing numbers therefore have to take account of the need for staff to double check completed work, ensuring catastrophic mistakes are avoided.

ORR analysis of Network Rail’s spending shows that in 2019/21, Network Rail spent £2.9 billion on renewing infrastructure and equipment. Last year that figure rose to £3.9 billion. Commercial profits on these renewals projects are reckoned within the industry to be around 6%.13 That means that outsourced renewals work is likely to have generated profits of around £175 million in 2019/20 and £235 million last year. This is despite the fact that as recently as the Stonehaven crash in 2020 outsourced work was found not to meet Network Rail specification, leading to a fatal derailment.14

At the same time that the industry faces drastic cuts, and a return to levels of essential maintenance that lead to several fatal disasters before RailTrack which was privately owned was replaced with Network Rail in2002.

Threats to services

Unions and operators have been clear that the proposed cuts threaten to push the rail industry into a process of managed decline. As reliability and quality of services slump, it will alienate passengers. Future funding is partially dependent on “customer satisfaction” so the industry risks a situation where drops in satisfaction and cuts to funding become mutually reinforcing.

This means we would lose the economic benefits that derive from a well-funded and efficient rail industry. And this is a major setback during the crucial decade when we must transition away from private cars if we want to meet our climate commitments.

Although services are dependent on their own funding settlements and organisational structures, it must be stressed that threats to the maintenance schedule are also threats to services. Operators cannot safely run services on infrastructure where maintenance is overdue or overrunning due to cuts to infrastructure management.

- 1https://gov.wales/written-statement-future-rail-update

- 2 https://www.lner.co.uk/about-us/who-runs-lner/

- 3 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-51298820

- 4 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-kent-58716625

- 5 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-56432919

- 6 DfT, ‘The Williams-Shapps plan for rail’, [https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/great-british-railways-willi…], May 2021

- 7The Guardian, ‘‘Back to the bad old days’: swingeing rail cuts set alarm bells ringing’, [https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/dec/05/back-bad-old-days-swin…], December 2021

- 8The Guardian, ‘Network rail joins the public sector, but don’t call it nationalisation’, [https://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/aug/28/network-rail-piublic-s…], August 2014

- 9 Network Rail, ‘Our CP6 targets and financials, May 2021 update

- 10 The 2017 European Rail Performance Index, [https://www.bcg.com/fr-fr/publications/2017/transportation-travel-touri…], April 2017

- 11 TUC analysis of data from Office of Rail and Road ‘Rail industry finance (UK)’, [https://dataportal.orr.gov.uk/statistics/finance/rail-industry-finance/], November 2021

- 12 Network Rail, ‘Our CP6 targets and financials’

- 13 ORR, ‘Rail industry finance (UK)

- 14The Times, ‘Carillion’s drain mistakes blamed for fatal crash at Stonehaven’, [https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/4b8851e2-9ff6-11ec-b38e-10b333e9179b…], March 2022

Alternatives

Insourcing

The benefits of a decent funding settlement for rail services are clear. Nonetheless there are also significant savings that could be delivered by bringing outsourced services back in house.

Analysis by the RMT union identified that insourcing even half of Network Rail’s outsourced renewals work would save around £115 million, currently leaking out in commercial profits on outsourced contracts, enough to prevent the cuts in maintenance work that are being envisaged.

Network Rail paid out £75 million to its contractors in facilities management, including around £28 million to shadowy outsourcing giant Mitie, and a further £6.4 million to its subsidiary Interserve.15 This outsourcing is not only a waste, but also has a very real impact on workers. Companies like Interserve are contracted to employ staff at the bottom end of the pay scale like cleaners, very often migrant workers, isolating them from the robust trade union protections enjoyed by ‘in-house’ staff and deepening the exploitation of these vital key workers. With commercial profit margins on facilities management contracts at 6%, this means that Network Rail could save a further £4.5 million by insourcing this work and cutting the profit extraction from facilities management.16

Public ownership

The end of franchising opens up the potential to deliver the truly radical change the industry needs. Rather than contract out to private operators, Great British Rail could take ownership of the lines and services.

This would have the effect of ending the huge levels of profit leakage to private companies and shareholders. In 2012, the Rebuilding Rail report estimated that this could be worth £1.2bn a year compared to the old franchising system.17

In addition, this would allow truly coherent oversight and provision of the full range of services and functions within the rail industry including track and infrastructure maintenance as well as the train services. The coherence would ensure that the profit motive would not interfere with essential services and would prevent the need to manufacture competition within the industry, which has no function other than to drive down terms and conditions for staff.

How does the British railway model compare internationally?

Britain’s failed experiment with rail privatisation is almost unique in the world. Although other countries have implemented liberalising reforms, in the UK the depth and breadth of disorganisation and cost it imposed on the industry and those who rely on it is unparalleled.

Despite the UK rail industry’s extreme fragmentation, there are many points of international comparison which shed light on what has gone wrong, and what can be done to fix it.

The European model

Sweden was the first European country to embark on the project of rail liberalisation. The Swedish government took steps to introduce a private access and competition in 1988. It began by separating the infrastructure and operational arms of the state railway monopoly, Statens Järnvägar (SJ), into two separate companies, with operations remaining with SJ and a new state-owned company, Banverket, managing infrastructure.18

The reform was meant to create the basis for a fully privatised network by 1994, but the project was halted and Sweden’s rail model is now broadly reflective of the European standard - a publicly owned umbrella company divided internally into financially and managerially separate units in charge of infrastructure and operations, respectively.19

As in Britain, liberalisation in Sweden was following by a sharp rise in public cost, although this is partly on account of much needed capital investment and upgrading. Sweden stopped short of attempting to privatise its infrastructure arm and SJ also remained in public ownership and with a near monopoly on long distance passenger operations. SJ continues to provide 82% of services, with most of the remainder being transferred to the oversight of local authorities.20

Funding has since stabilised, with the Swedish state providing approximately EUR 2 billion in total public spending on its railway network per year.21 When adjusted for difference in size between the Swedish and UK rail network, this amounts to roughly 10% more than the UK, with a corresponding increase in service quality and affordability.22

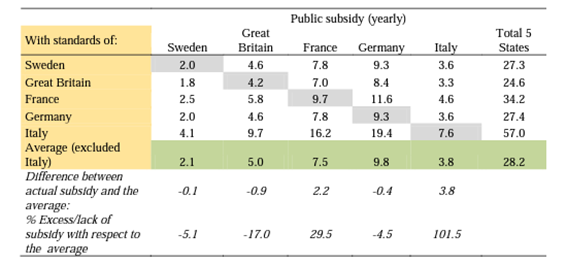

The table below shows the yearly public subsidy to rail in various European countries in 2012, shown in billions of Euros. It also shows what the public subsidy for each country would be calculated at the rate of each other country.

- 15RMT analysis of Network Rail, ‘Spend over £25,000’,[ https://www.networkrail.co.uk/who-we-are/transparency-and-ethics/transparency/our-information-and-data/#business-ethics],

- 16Ibid

- 17Transport for Quality of Life, ‘Rebuilding Rail’, [https://doczz.net/doc/8490860/rebuilding-rail---transport-for-quality-o…], June 2012

- 18Transport for quality of life: Rebuilding rail (2012), p.53

- 19University of Milan: Public expenditure on railways in Europe (2014), p.25

- 20Transport for quality of life (2012), p.53

- 21University of Milan (2014), p.27

- 22Boston Consulting Group: The European railway performance index (2017)

The standout fact revealed by these findings is that applying the UK funding model to Sweden, France, Germany, or Italy, would result in real terms cut. The UK railway is, proportionally, the least funded of the group while Sweden is closest to the overall average.

European railways, including the French, German, and Italian networks, also receive indirect public subsidy in the form of debt transfer to the state, which can borrow cheaply and amortise debt more efficiently.23 When the rail network is public owned, this represents a simple efficiency saving, but where privatisation is present, this represents a catastrophic cost to the public purse.

The UK has unusually low levels of public investment and remarkable depth of privatisation. For example, the Italian state provides the rail network with approximately twice the relative level of funding than the UK. As we can see from the table above, the other main European networks fall somewhere in between.

It is important to remember that funding matters. The relationship between funding levels and performance, as demonstrated by the European Railway Performance Index, is basically liner. The UK’s mid-ranking status on the index - well behind France, Germany, and Sweden - is bolstered by its (now) excellent safety standards. This disguises to some extent how far the UK falls behind on quality and affordability of service.24

Natural Monopolies

The now standard model of railway organisation in Europe has resulted from the collision between the continent-wide political movement towards marketisation and the cold, hard fact that railways are critical economic and social infrastructure which require sustained public funding and long-range planning.

Most of the continent’s major networks have been reformed to separate infrastructure management from passenger and freight operations. In practice, this means that previously integrated railway companies have been converted into state holding companies composed of discrete operational units, not unlike what is now being proposed for Great British Rail

But railways are ‘natural monopolies’ for a reason. They require very high levels of capital investment at extremely slow returns. The concentrations of investment capital required is usually only accessible to states. Railways also require a high degree of integration to run safely and efficiently, impeding competition and presuming an overarching planning body.

The liberalisation policies implemented by many European governments from the late 1980s onwards disaggregated these monopolies, with a view to improving prospects for private sector penetration. However, the reforms encountered stiff resistance from the railway networks themselves, as in the case of Germany’s Deutsche Bahn (DB), which was forced to liberalise through court action.25

Even where there was a political will to reform, as in the UK, the process failed to generate the expected results. Both public spending26 and cost to the consumer27 have gone up significantly since privatisation.

New Zealand, for example, initially adopted the franchise model with enthusiasm. Their network was privatised in 1993, after the transference of NZ$1 billion dollars of railway debt to the state. However, in 2003 the NZ government was forced to renationalise its infrastructure manager and in 2008 it committed to bringing in passenger operators as well, reintegrating them into a new state operator ‘KiwiRail.’ KiwiRail is now run on a ‘non commercial’ basis and the government has committed NZ$2 billion in investment for a major modernisation and improvement plan.

Railways are a public good

The first step to achieving the best possible railway network for the UK is achieving a widespread consensus on the social and economic purpose of the railways.

In most cases, the social function of rail is implicitly understood, while in others, such as in Germany, it is formalised within their constitutional arrangements. For example, the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany guarantees that “in the expansion and maintenance of the rail network [...] the common good is to be taken into account” and the Federal Government fulfils this infrastructure mandate by making funds available for capital expenditures.28

A high quality and comprehensive public transport system is good for society and good for the environment.29 And there are direct and indirect economic benefits from proper railway funding. According to a study commissioned by the Railway Industry Association:

- “in 2019, the sector contributed £42.9 billion to the UK economy … This was associated with 710,000 (employee and self-employed) jobs, and £14.1 billion in taxation. As the £42.9 billion total footprint is 3.5 times the £12.2 billion GVA of the railway system itself, we can say that, for every £1 worth of work on the network itself, a further £2.50 of income is generated in associated industries, their suppliers, and firms supported by railway workers’ wage-funded spending.”30

Railway investment is like health and education spending. It has a ‘multiplier effect’ which means that it generates lots more money for the economy than the original investment.

This means that it is worth investing in railways, and prioritising the social and environmental benefits which they bring. Rather than just focusing on the ones that generate the most profits. Railways are a vital public service.

ROSCOs

A unique drain on British railway finances are the entities known as Rolling Stock Companies, or ROSCOs. The ROSCOs were created in the wake of privatisation to act as holding companies for rolling stock, and which they then lease out to private TOCs.

Privatised ROSCOs serve no function other than to drain money out of the system. A sustainably funded, integrated, railway would have complete ownership of its own trains, as is the standard everywhere in the world.

Sustainable funding

The second step to restoring a world class railway is achieving clarity on what is meant by proper funding. Excluding alternative revenue streams like advertising and commercial property holdings, railways are generally funded in the following ways:

- Fare revenue and charges collected directly by the TOCs and freight operators.

- State subsidies to operators for running costs.

- State or private financing in the form of commercial loans.

- Revenues collected by infrastructure managers from tolls charged to operators.

- Direct state funding for capital investment infrastructure management through grants.

- Indirect subsidy via debt transfer from rail companies to the public balance sheet.

As the example of the ROSCOs illustrates, a sustainable funding model is deeply entwined with a sustainable organisational model. At the very minimum, this means grouping all the divisions of the railway into an overarching, publicly owned, holding company on the European model. The need for reorganisation of this sort has already been admitted by the UK government in the findings of the Williams Report and the announcement of Great British Railways. However, the UK can and must go further.

The UK must recognise that increased public investment in rail has a direct correlation with increased quality of service. It is theoretically possible for there to be an upper limit on the relationship between investment and performance, but the UK is nowhere near that point.

Integration

Our railway industry is divided between organisations that run the trains and the ones that are responsible for maintaining infrastructure. This is ineffiecient. Great British Railways will be responsible for both. Industry experts call this vertical integration.

But the industry should also integrate the multiple services run by different TOCs so that a single, public owned operating company ran all the train services; instead of paying different TOCs a flat fee to run the services. That would stop money leaking out through private profits and dividend payments that could be reinvested.

That investment could be used to support the government’s levelling up agenda. For instance it could provide more well-paid, skilled jobs with a good career path and clear progression.

At the moment multiple organisations compete to run services within the industry. As well as the money that leaks out through private profit, there is money wasted through duplication of functions across all those organisations. Multiple marketing teams, HR departments etc all the costs of which all eventually get passed on to the government and passengers.

The European model of organising separate infrastructure management and service operations but within a single publicly owned body is better than the alternative of having them under entirely separate but it would be better to do away with this separation all together.

The creation of Great British Rail is an opportunity to avoid the errors of the past not to repeat them.

- 23University of Milan (2014). For the French example, see p.22, for Germany, p.16, and for Italy, p.10

- 24The European railway performance index (2017)

- 25UK Government: Williams rail review - current railway models, Great Britain and Oversees (2019) p.10.

- 26House of Commons Library: Railways – government support and public expenditure (2014)

- 27https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/train-fares-rail-t…

- 28https://ir.deutschebahn.com/en/db-group/capital-expenditures/

- 29See, for example, International Transport Workers’ Federation: The future is public transport (2021)

- 30Railway Industry Association: The economic contribution of UK rail (2021), p.3

Conclusion and Recommendations

The British rail industry is at a pivotal stage. After two years of depressed passenger numbers and emergency measures, passengers are increasing. But the industry is still in a fragile state. Many passengers will have changed their working patterns or have switched to private vehicle use. It is vital that passengers keep returning to rail, if the industry is going to deliver to its full potential. Moreover, rail is a low carbon transport mode, of the type we will need to encourage if Britain has any chance of meeting our climate commitments.

The government has an opportunity to ensure the industry can play its part in driving our economy and meeting our climate commitments.

If the government can commit to providing a sustainable transport settlement, we can avoid a situation of managed decline and preserve the UK’s current record for rail safety. The alternative is to risk a vicious spiral where reduced maintenance and declining services drive lower and lower ticket sales further shrinking the budget for investment. Meanwhile the shift to higher carbon modes of transport becomes permanent.

However, if they were willing to make truly radical changes and bring the industry into public ownership, it would be able to deliver on its potential. Money that currently leaks out to private operators’ profit margins, and shareholders’ dividends could be reinvested into ensuring safety and service provision are at a high standard. That staffing levels stay at a responsible level and vital improvements like electrification go ahead.

Such a change might seem ambitious, but it would only put us in line with the status quo across Europe.

In fact, when we assess the level of cuts currently being threatened and the impact this would have on service levels and safety for passengers, current government policy seems to be the riskiest choice of all.

Recommendations

- Government should increase funding to Network Rail and scrap the requirement for so-called efficiency savings.

- Government should formally recognise the railways as an essential public service, to be run on a non-commercial basis where there are clear social, economic and environmental reasons to do so.

- Network Rail should bring all outsourced services back in-house.

- Government should commit to integrating all train services not devolved to regional authorities via a single operator, uniting track and train under public ownership.

- ROSCOs should be brought into public ownership and measures should be taken to improve public capacity in fleet maintenance and manufacturing.

- Government should finance upgrades, including electrification and new lines, to significantly displace passenger miles travelled by car, in line with the UK’s climate leadership ambitions.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox