Building solidarity, stopping undercutting

This section sets out why the government’s immigration plans will lead to increased exploitation and discrimination, and lead to skills shortages that could damage our public services.

Increased exploitation

Too many workers are already being exploited and undercutting is taking place due to the government’s failure to provide workers with strong rights at work. Over three million workers are on insecure contracts, including agency work, low paid self-employment and zero-hours contracts. Many of these workers are not given enough hours to have the right to holiday or sick pay and are often working on worse terms and pay than directly employed workers or those on more secure contracts.

Not enough employers, particularly in the private sector, collectively bargain with unions to guarantee equal and decent treatment for all workers. While 57.6 per cent of workers in the public sector are covered by a collective agreement and 51.8 per cent are members of a trade union, only 15.2 per cent of workers in the private sector are protected by a collective agreement with only 13.5 per cent members of a trade union.1 .

The ISSC will lower standards for workers further by removing the right of EU citizens to work for an unlimited period in the UK, requiring them instead to work on time-limited visas. Workers on these visas will be vulnerable to exploitation and being used to undercut other workers. This would particularly be the case for workers on the proposed low skill work visas as they would only be allowed to be in the country for a short period and work in a restricted range of jobs.

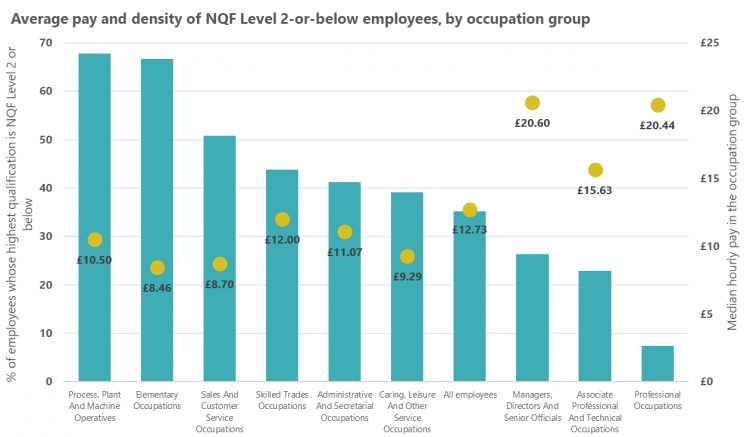

Table 1 shows that the sectors where the majority of jobs are classified as ‘low skill’ – process operatives, elementary occupations such as cleaning, agricultural work and sales/customer services - the median hourly pay is low. This is due to low union density and weak coverage of collective bargaining in these sectors. EU workers on low skill visas are thus likely to be employed in low paid jobs where they will be vulnerable to exploitation due to low trade union coverage and discouraged from leaving their employer for fear of losing legal status in the country.

- 1BEIS (2018) “Trade Union Membership 2017”, available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/712543/TU_membership_bulletin.pdf

Table 12

Furthermore, if a worker stayed longer than 12 months on the new low-skill visa they would become undocumented and unable to claim rights at work. This is due to the fact that the Immigration Act (2016) made undocumented work a criminal offence. This means workers face a potential prison sentence if they report abuse to the authorities.

The TUC also has concerns that the government has said that there will be ‘behind the border’ checks on immigration status on workers crossing from the Republic of Ireland to Northern Ireland. This will also concentrate power in the hands of employers who would be able to threaten to report workers with uncertain immigration status to the authorities if they resist exploitative treatment.

Bad employers are already using immigration rules to prevent undocumented workers from outside the EU claiming their rights. This was illustrated in 2016 when Byron Burgers called immigration officials to investigate workers who were attempting to build a union campaign for a living wage as they knew some of the workers in the campaign had uncertain immigration status. This resulted in immigration officials questioning and arresting key activists in the campaign, some of whom were subsequently deported. This was a blow to the campaign to increase wages for all workers.

Past experiences with restrictive visas systems have shown that workers on such visas often can’t leave abusive employers without losing their legal status in the country.

Between 20 and 2013 the government ran a Seasonal Agricultural Workers (SAWs) scheme which issued work visas to workers from central and eastern Europe that were limited to jobs in agriculture. There were strict restrictions on the visa which made it almost impossible in practice for workers to change employer. This meant that employers were able to force workers on the SAWs scheme to accept abusive conditions and lower terms and conditions than other workers. Those who left abusive employers to find new work lost their status in the country which left them open to further exploitation (see Serge’s story, below). Therefore, the ISSC will fuel concerns about migration, rather than address them, by increasing the risk that migrants will be used to undercut other workers.

- 2Labour Force Survey (2018, average of the four quarters); Annual Survey of Household Earnings (2018), available at: ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/datasets/occupation4digitsoc2010ashetable14

Experience of temporary work permits in other countries also suggest that they are likely to fuel exploitation, both of migrant workers and those already resident.

Canada

In 2015, the Canadian government introduced significant restrictions to its temporary foreign worker programme including strict quotas and restricting the ability of workers on these visas to change employers. Trade unions in Canada raised concern that these visas increased exploitation of migrant workers, particularly in agriculture and care, as workers were too afraid of losing their legal status to leave abusive employers.

The United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) union in Canada described that this visa scheme created an ”atmosphere of fear” amongst migrant agricultural workers and that ”our staff at the migrant worker support centres often report incidences of untreated illness and injury because of the fear associated with accessing medical benefits that could signal to their employer possible productivity losses, and trigger repatriation.”3

As a result of public and union opposition, the temporary foreign worker programme was overturned and a less restrictive system that provided routes to permanent residency was introduced in 2017. 4

Australia

Workers under 31 years of age can work in Australia for a year on a Working Holiday visa. Holders of this visa can work in any job but cannot be employed on any job for more than six months. Trade unions in Australia have documented that the temporary nature of this visa has been used systematically by some employers to abuse workers. The ACTU union centre has highlighted cases of exploitation of workers on working holiday visas in the agricultural and hospitality sectors, with cases of underpayment, substandard accommodation and debt bondage. Evidence from the Australian Fair Work Ombudsman revealed that in 2016 that 28 per cent of workers on the working holiday visa did not receive payment for work undertaken and 35 per cent stated they were paid less than the minimum wage. 5

Brexit

The ISSC stands to weaken workers’ rights further by undermining the UK’s chances of getting a Brexit deal that will protect rights and jobs.

The bill would allow the introduction of a restrictive immigration regime that is incompatible with the rules of the single market which the TUC has said, along with a customs union, is probably the best way to ensure UK workers continue to be protected by the same level of rights as workers in the EU, protect jobs and protect peace between Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland.6

Increased discrimination

The ISSC would require EU workers to demonstrate they had the correct visa to access employment, healthcare, banking and housing, increasing the number of document checks taking place across society. This risks significantly increasing discrimination against BME groups.

We know that BME groups have been disproportionately targeted in the document checks for banking, health services, employment and housing that were introduced or expanded by the Immigration Acts 2014 and 2016. These acts were introduced as part of the intention Theresa May declared, while still home secretary in 2012, to create a ”really hostile” environment through its immigration policies.7 Recently the high court ruled that the document checks required for landlords by the Immigration Act 2014 were discriminatory and breached human rights laws, as evidence showed BME groups had been disproportionately targeted.8

The document checks introduced by the Immigration Acts, combined with the Home Office’s failure to keep accurate records of immigration status, has led to many cases of BME workers losing their jobs and being denied health care and housing as exposed in the Windrush scandal that broke in the media in 2018. Cases that came to light included those of workers such as Glenda Caesar who worked in the UK for 50 years but was fired from her job in the NHS, as the Home Office did not have accurate records of her legal status in the country.9 .The additional document checks required by the immigration and social security coordination bill would mean BME groups were put at further risk of losing access to vital services and their jobs.

The TUC has also raised concerns that the document checks rolled out by the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016 have led to workers in health, housing, education and banking being told by employers to check people’s documents ahead of providing them with care or a service. In the case of health workers, such demands undermine their ability to fulfil human rights obligations to provide care to those in need. The TUC is concerned that further requirements for document checks through the governments new immigration proposals would only increase the pressure on workers to be border guards, rather than providers of vital services.

Damaging public services

While the government has attempted to scapegoat migrants for strains on public services, it is clear that they are caused by the government’s failure to properly fund public services and the salaries of public sector workers.

The government’s austerity agenda has seriously damaged health, education and housing services across the country. The north of England has particularly borne the brunt of cuts to local authority budgets that provide childcare, social services, library, and other services. Centre for Cities analysis revealed that residents in cities in the north have experienced spending cuts of 20 per cent compared to cuts of 9 per cent to cities in the South West, East of England and South East, excluding London. 10

Meanwhile the government’s failure to fully fund pay in the public sector has led to serious staff shortages. The pay of many public sector workers has not caught up after a seven year pay freeze. Prison officers, civil servants and school leaders are still being offered below- inflation pay rises. None of those offered pay rises have caught up on the years they lost during the years of the pay cap. TUC analysis released last year found that a range of different public sector occupations were earning between £3,000 and £6,000 less in real terms than they were in 2010. School teachers’ pay, for example, had declined by up to 15 per cent in real terms. Poverty pay remains a massive problem in outsourced areas, most notably in social care services. 11

The starting salary of newly qualified nurses on Band 5 is less than £30,000. Nurses must progress to the highest point in the band over four years to reach the £30,000 pay mark. About 50 per cent of Band 5 nurses will be below the top of the band. A prison officer’s starting salary is £22, 843 and a teacher’s starting salary is £23,720.

Staff shortages in the public sector have also been caused by the government’s failure to properly invest in skills – discussed in section D.

Staff shortages in the public sector and cuts to public services would be made worse by the restrictive immigration system the ISSC would allow to be introduced. A comprehensive analysis by UCL calculated that EEA migrants contribute £2bn net to the Treasury every year.12 . The government’s white paper on immigration estimates that the government’s planned restrictions on migration could result in reductions of up to £4bn in national revenue that could have been spent on providing quality public services.13

The government’s proposed new work permit scheme for EU workers and salary thresholds will also reduce the number of staff available to play critical roles in the health, social care and other parts of the public sector where there are already shortages. Over 60,000 staff in the NHS alone come from the EU.14

The planned restrictions for visas in ‘low skill’ jobs would also radically reduce the number of workers available to work in the care sector and other care assistant jobs in the NHS, as the majority of these jobs would be classified as ‘low skill’ due to the fact they do not require NVQ Level 3 qualifications or above. 15

The government’s proposal to introduce a salary threshold of £30,000 for EU workers to be eligible for the new skilled visa, meanwhile, would also reduce the number of workers available to work in crucial roles in public services. As noted above, the starting salary for nurses, firefighters and teachers as well as a number of other crucial public service jobs, is below £30,000.

Increased skills shortages

The TUC is concerned that restricting EU migration and failing to increase investment in skills will increase the shortages key sectors of the economy and public sector are already facing.

There has been a worrying fall in investment in skills by employers despite clear skills shortages. Table 2 shows that in sectors facing some of the highest skills shortages, such as agriculture, utilities and health and social care, investment in training has fallen in the last two years. The government’s decision in 2017 to cut bursaries for nurses and allied health professionals was one of the most significant cuts to skills funding. The number of applications to study nursing has fallen by a third since these cuts were made.16

- 3UFCW (2015) The Status of Migrant Farmworkers in Canada, available at: ufcw.ca/templates/ufcwcanada/images/directions15/october/1586/MigrantWorkersReport2015_EN_email.pdf

- 4Meardi, Guglielmo (2017) ”What Does Migration Control Mean? The link between migration and labour market regulations in Norway, Switzerland and Canada” available at: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/wbs/research/irru/wpir/wpir_109.pdf

- 5ACTU (2018) ”Permanent vs. Temporary Migration” available at: actu.org.au/media/1033807/a4_ctr_migration_briefing.pdf

- 6O’Grady, Frances (2019) ”Theresa May is Trying to Pull the Wool Over Our Eyes on our Post-Brexit Rights”, available at: huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/brexit-workers-rights_uk_5c668d82e4b05c889d1dfed5

- 7May, Theresa (2012) Speech to Conservative party annual conference, available at: politics.co.uk/comment-analysis/2012/10/09/theresa-may-speech-in-full

- 8 BBC News (2019) ‘”Right to rent” checks breach human rights’, available at: bbc.co.uk/news/uk-47415383

- 9ITV News (2019) “Windrush Generation NHS Worker Lost Job and Faces Deportation Despite Living in the UK for More than 50 Years”, available at: itv.com/news/2018-04-11/windrush-generation-nhs-worker-lost-job-and-faces-deportation-despite-living-in-the-uk-for-more-than-50-years/

- 10Centre for Cities (2019) ”Cities Outlook 2019”, available at: centreforcities.org/press/austerity-hit-cities-twice-as-hard-as-the-rest-of-britain/

- 11TUC (2019)“Five Reasons NHS Workers are Still Getting a Raw Deal on Pay”, available at: tuc.org.uk/blogs/five-reasons-why-public-sector-workers-are-still-getting-raw-deal-pay

- 12Dustmann, Christian and Frattini, Tommaso (2014) The Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK ucl.ac.uk/economics/about-department/fiscal-effects-immigration-uk

- 13HM Government (2018), “The UK’s Future Skills-Based Immigration System”, available at: gov.uk/government/publications/the-uks-future-skills-based-immigration-system

- 14House of Commons Library (2018), ”NHS Staff from Overseas: statistics”, available at: https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-7783

- 15IPPR (2018) “‘Fair Care: a workforce strategy for social care”, available at: ippr.org/files/2018-11/fair-care-a-workforce-strategy-november18.pdf

- 16Nursing Times (2018), ”Nursing Course Applications Have Crashed by Third in Two Years”, available at: nursingtimes.net/7025246.article

Table 2 17

Research from IPPR shows that UK employers invest half as much in vocational training per employee as the EU average. Countries such as Belgium, Sweden and Germany spend well above the average.18

The government’s Employer Skills Survey 2017 revealed that 38 per cent of employees received no training in the past year (no change from the findings in the 2013 and 2015 surveys) and a third of UK employers admit that they have not trained any of their staff in the past year (this statistic has remained at this level since the survey was first undertaken in 2005).

A recent Institute for Fiscal Studies report highlighted a number of worrying trends in public investment in adult skills. It stated that further education ”has been a big loser from education spending changes over the last 25 years, highlighting that spending and numbers in further education have both fallen significantly over time.“ The total number of adult further education learners fell from 4 million in 2005 to 2.2 million by 2016. The report estimated that total funding for adult education and apprenticeships fell by 45 per cent in real terms between 2009 and 2010 and 2017 and 2018.19

The combination of funding cuts and the introduction of tuition fees in the college sector has caused a dramatic fall in adult participation rates in education. The latest annual Adult Participation in Learning Survey commissioned by the government has recorded the lowest participation rate (37 per cent) since the survey began in 1996.20

- 17Department for Education (2018) Employer Skills Survey 2017 gov.uk/government/publications/employer-skills-survey-2017-uk-report

- 18IPPR (2017) Skills 2030: Why the adult skills system is failing to build an economy that works for everyone, available at: ippr.org/files/publications/pdf/skills-2030_Feb2017.pdf

- 19Institute for Fiscal Studies (2017) ”Long-Run Comparisons of Spending per Pupil Across Different Stages of Education”, available at: ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/comms/R126.pdf

- 20Department of Education (2018) Adult Participation in Learning Survey, available at: gov.uk/government/publications/adult-participation-in-learning-survey-2017

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox