Why the rate rise will hurt working people

Normally, interest rates going up is a sign that the economy is booming – and the Bank thinks that inflation is set to rise too far above their two per cent target, threatening the stability of the economy. Inflation is already well above target – at three per cent in the latest figures (on the CPI measure, though plenty would point to the RPI at 3.9). But this isn’t because the economy is strong. And unless the Chancellor steps in to help the economy at the Budget, a rate rise will only make it weaker.

The rate setters at the Bank of England have to bear in mind the impact of their decision on inflation first of all. But they also will also want to take into account what this means for wages, for borrowers, savers, and for the wider economy. For savers, a rate rise could be a good thing. For everyone else, not so much.

Inflation and wages

Inflation – rising prices - hurts working people when wages aren’t rising to compensate.

After the referendum, inflation went up, as the value of the pound fell, and the price of imported goods rose. The rate at which wages were rising in nominal (before inflation) terms, slowed further.

The result is that real (after inflation) wages are falling again – a continuation of Britain’s terrible pay performance since the financial crisis.

Normally, the Bank would expect higher inflation to drive higher wage growth. But there’s no sign that this is happening.

Borrowing and debt

In part due to weak wage growth, consumers have had to resort increasingly to credit.

A rate rise could increase the amount borrowers need to spend paying off their debts, putting living standards under further pressure.

The economy

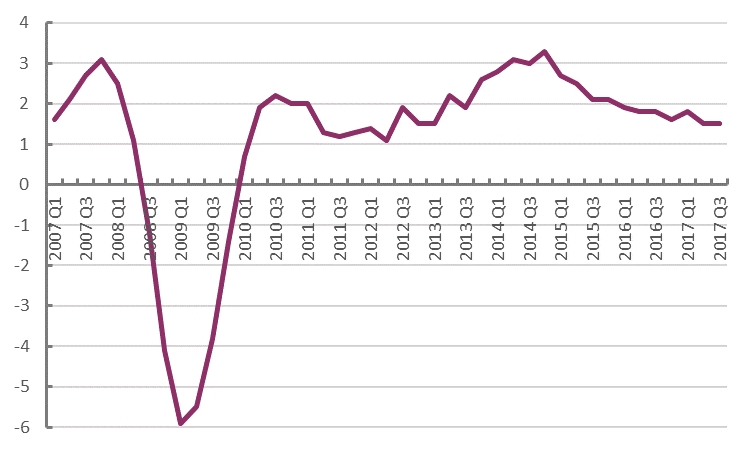

With net trade faltering, investment still subdued and consumption stalling following subdued wage rises and higher prices, economic growth in 2017 is now weaker than any point since the most severe austerity in 2011 and 2012.

GDP, % four quarter growth

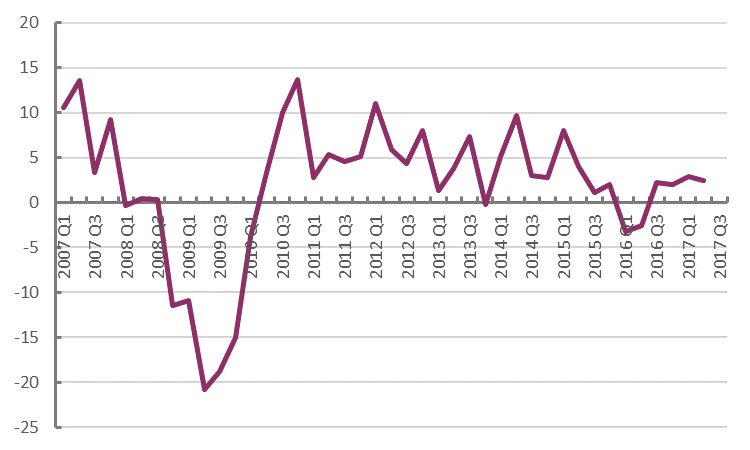

Low interest rates are meant to encourage businesses to borrow to invest. But business investment has been subdued since 2011, and at 2.5% in 2017 Q2 is little better than stagnant.

Business investment, % four quarter growth

Normally, rising inflation is a sign of a ‘boom’, and interest rises a sign that the Bank thinks that the economy needs cooling. This time, it seems that it’s a message that the Bank thinks the economy can’t grow any faster – so rates might as well rise now.

Pensioners, savers and interest

And in the meantime low interest rates hurt pensioners and savers. Lower rates mean lower annual returns on savings, and the reduced interest on financial instruments (not least government bonds) leads to inflated reported pension deficits.

Only the Treasury can resolve policy dilemmas

The current situation is a dilemma for policy makers. Inflation is high – but not because of a booming economy. Low interest rates are hurting savers – but not encouraging companies to borrow to invest.

But putting up interest rates will not resolve this dilemma. Such an action is likely to damage economic growth and hurt those relying on borrowing to support their living standards.

Nor is an interest rate rise necessary to reduce inflation. Without wages picking up in parallel to inflation, inflation will go away of its own accord. The effects of the falling exchange rate on import costs are likely to be a one-off hit to prices, not a repeated hit every year.

Others might point to the economic idea of a NAIRU – non-inflation accelerating rate of unemployment. This suggests that when unemployment falls below a certain point wage inflation will kick in. But unemployment has repeatedly fallen below that point since the financial crisis and wage inflation is falling not rising.

To solve these dilemmas we need to turn away from the Bank, and towards the Treasury. As he cut rates in the wake of the referendum, Mark Carney made it clear that monetary policy could only do so much – and this was widely interpreted as a call for government to step in and play its part. We need that boost in government spending now to support demand and inject some confidence into the economy, at a time of increased uncertainty.

But in the absence of government action, it’s hard to see how a rate rise could help. The most recent rate cut was put in place to support the economy after the referendum. Economic growth is close to half its long-term average before the crisis of 2.7% and doesn’t look like it’s getting much stronger. More not less stimulus is necessary.

Image: George Rex

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox