Reasons to be cheerful about productivity

It’s a common experience; your computer stops working, and you have no idea why. You call the IT experts to describe the problem. While you wait for the response, you restart, shut down altogether, and finally turn it off and on again at the plug.

Most of the time, it starts working again, though you, never really understand how. But you do know that these techniques work often enough to be worth trying.

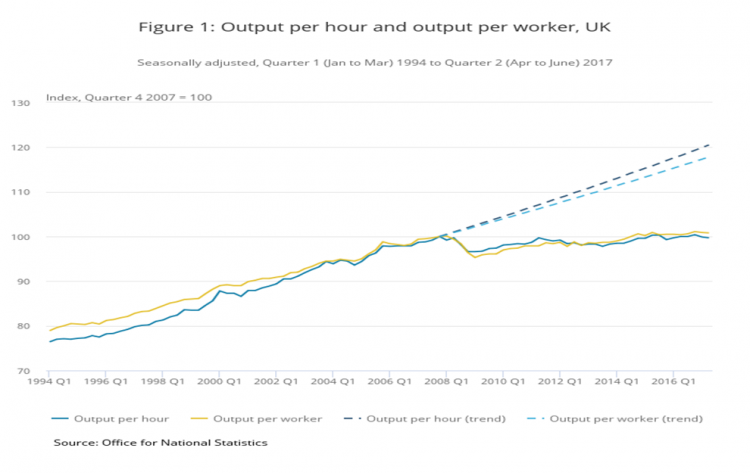

The British economy is currently in frozen screen mode. Productivity – the amount we produce per hour of work – has been flat for a decade, and in the first half of this year appears to have actually fallen (see the chart below). Those we normally turn to for expertise don’t seem to know what’s gone wrong.

But rather than trying to use the tools we think might work, the response seems to be to simply stare at the screen in despair.

There are of course reasons to be gloomy. Poor productivity is pressing down on wages, with business’ failure to increase output per hour one, but not the only factor holding back pay packets. And they’re bad for the public finances too.

The Office for Budget Responsibility today confirmed that previous hopes that the productivity figures would spring back into life of their own accord have proved misplaced, leaving lower expected growth, lower expected tax revenues, and a headache for the Chancellor. And there’s little consensus on just why the figures are so bad.

The ONS suggested this week that a move in jobs towards service sectors, where productivity is lower than manufacturing, could help explain some of the downgrade. But at the same time, new research showed that measurement error might be explaining a lot of what’s going on when we try to explain the fall in productivity in this way, labelling productivity a ‘mystery’ – a change in tone but not sentiment from the now much repeated ‘productivity puzzle’.

While we don’t know exactly why British productivity has been so weak for the past decade, we do have a fairly good idea of some of the things that have got productivity rising again in the past. And the reason to be cheerful is that these various forms of restart button are things we would want to do anyway – even if our productivity figures weren’t currently so puzzling.

Re-start button one would be simply for the government to restart an investment programme. You can argue, as my colleague Geoff Tily does here, that the productivity figures are an artefact of weak demand. Taking a different tack, you could borrow from the OECD to argue that weak business investment in machinery and technology help explain the failure of businesses to become better at producing goods and services, and that government is best placed to step in to fill the gap. Or you could think that investing in better transport links, faster broadband, or more affordable housing seem not only likely to make life easier for businesses and workers, but desirable things in and of themselves – particularly at a time when the government faces low borrowing costs.

Let’s say that you reject that the demand side has anything to do with productivity. Don’t worry – you’re not yet out of tools that not only might make a difference, but are desirable in their own right. Research we commissioned from the Learning and Work Institute suggests that there is a reasonably strong correlation between lower productivity sectors, and the rise in insecure work. And it makes pretty intuitive sense that workers in lower paid, insecure jobs who don’t know their hours of work, miss out on sick pay, holiday pay and parental rights, and don’t have their voice heard at work, might be less productive.

And if better rights, protections, and pay for insecure workers don’t fix the productivity puzzle? Well, at least millions of workers will have better rights, protections and pay, and the chance to make their voice heard.

You could go one step further in win-win supply side interventions and invest in some training too. The government apprenticeship programme is welcome. But meanwhile, investment in adult skills fell by over 40 per cent under the coalition government, and investment in continued vocational training for employees is half the European average. You don’t have to believe that this is the only factor that explains why the UK’s productivity is some 15 per cent behind the rest of the G7 to believe that it might be a factor. Or to think that, in the face of rapid technological change, investing in workforce skills should be a priority in any productivity scenario.

And your options don’t end there while waiting for experts to explain the problem. You could look to improve the U.K’s record of poor management practices. Or think about how to ensure that high productivity firms better share their success with their supply chains – as Andy Haldane has been arguing. Or better, you could take all of these approaches – in the belief that each of them might address a persistent problem faced by the U.K. - rather than waiting for the answer to the puzzle to present itself if only we stay on hold for long enough.

That’s what we’ll be arguing the Chancellor should do when he delivers his Budget this year. Because the only thing currently more puzzling than the UK’s productivity performance, would be a lack of willingness to even try to address it.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox