No, EU rules won’t stop us building UK ships in UK shipyards

Prominent Brexiteers such as Liam Fox and UKIP’s Mike Hookem have recently claimed that EU rules will prevent the government from building military support ships in UK yards.

As usual when it comes to the claims of hard Brexiteers, these claims don’t stand up to scrutiny.

In reality, the government can choose to exempt military procurement from EU competitive tendering requirements for ‘warships of all kinds’ to protect its ‘essential security interests’, subject to certain conditions.

It also has the sole right to determine what these essential security interests are.

In fact, other EU nations place orders for auxiliary ships in domestic shipyards all the time, and the share of EU defence spending with domestic suppliers has actually increased since the Defence and Security Procurement Directive was passed 2009.

So it’s clear that EU rules have no bearing whatsoever on whether the government can restrict the upcoming Fleet Solid Support order to UK shipyards.

Debunking another Brexiteer myth

Unions representing workers in shipbuilding are campaigning for the upcoming Fleet Solid Support order to be placed in the UK – a call that has been supported by the Labour Party and the SNP.

In response, a small number of politicians have claimed that the either Article 346 of the Lisbon Treaty or the Defence and Security Directive 2009 prevent the government from restricting the order to UK shipyards. We’d like to address both of these claims in turn.

Article 346

When Liam Fox recently claimed that Article 346 only exempted ‘the most sensitive items’ from international tendering, he was quoting a statement from Veterans for Britain – a Brexit campaign group with close ties to Vote Leave – that appeared on the Guido Fawkes website.

Article 346 does not contain the words that were quoted in that post.

The actual wording of Article 346 (formerly Article 296) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is short and uncomplicated:

‘1. The provisions of the Treaties shall not preclude the application of the following rules:

(a) no Member State shall be obliged to supply information the disclosure of which it considers contrary to the essential interests of its security;

(b) any Member State may take such measures as it considers necessary for the protection of the essential interests of its security which are connected with the production of or trade in arms, munitions and war material; such measures shall not adversely affect the conditions of competition in the internal market regarding products which are not intended for specifically military purposes.

2. The Council may, acting unanimously on a proposal from the Commission, make changes to the list, which it drew up on 15 April 1958, of the products to which the provisions of paragraph 1(b) apply.’

Under the Article, EU Member States may exempt non-domestic suppliers from a competition (or place an order directly with a single supplier) under sub-paragraph 1(b), as long as it is for the purpose of protecting its ‘essential interests of its security’. Individual elements of a competition (such as the fitting of complex and sensitive systems) can also be exempted under the Article.

As discussed below, the maintenance of manufacturing defence capabilities is considered to be a legitimate security interest for the purpose of this legislation.

In 1958 the Council of Ministers published a list of general categories of materials that are eligible for the Article 346 exemption from international tendering. The list includes ‘warships of all kinds.’

The Fleet Solid Support ships will fulfil purely military functions and clearly meet any reasonable definition of ‘warships.’ Indeed, the planned Fleet Solid Support vessel has been described as a ‘warship’ by MoD Ministers.

The UK government’s categories of ‘complex’ and ‘non-complex’ vessels for tendering purposes represent an artificial and undefined distinction that has no basis in European or domestic legislation, and which could be overridden by a ministerial decision.

The Defence and Security Procurement Directive

Prior to 2009, defence orders were covered by general EU procurement rules that were often deemed inappropriate for sensitive security-related orders. In the Commission’s view, this was partially responsible for the high levels of reliance on the TFEU exemptions amongst Member States.

Consequently, the Defence and Security Procurement Directive was passed in 2009, which Member States had transposed into national legislation by 2013. The Directive sets out several new powers relating to security of information and supply that were intended to reduce dependence on Article 346 and gradually open up the European defence market.

Crucially, the Directive does not override or abolish the Article 346 exemption, which Member States can still invoke when they consider it to be necessary on the grounds of their essential security interests. The relevant passage of the Directive states that (emphasis added):

‘… the award of contracts which fall within the field of application of this Directive can be exempted from the latter where this is justified on grounds of public security or necessary for the protection of essential security interests of a Member State. This can be the case for contracts in the fields of both defence and security which necessitate such extremely demanding security of supply requirements or which are so confidential and/ or important for national sovereignty that even the specific provisions of this Directive are not sufficient to safeguard Member States’ essential security interests, the definition of which is the sole responsibility of Member States .’

Although the Directive is couched in the language of exceptional circumstances, there are strong grounds for concluding that the UK has interpreted this criteria on much more limited grounds than other EU nations (as discussed below).

It is also clear that the need to prevent job losses and ensure the maintenance of the UK’s sovereign defence manufacturing capabilities as the aircraft carrier programme winds down would constitute such exceptional circumstances. The MoD’s own guidelines (updated in December 2017) state that legitimate grounds for employing Article 346 include:

‘… a requirement to adopt security measures that limit information to UK nationals or maintain national industrial capability. Article 346 may be used in those circumstances to exempt a requirement from the DSPCR or to depart from the strict requirements of the DSPCR [the transposed UK regulations under the Directive].’

The MoD’s contemporary advice on the introduction of the UK’s transposed, which was published while Liam Fox was Defence Secretary, states that ‘the rules for using Article 346 (1)(b) TFEU have not changed.’

The Article 346 exemption therefore remains in place and can be invoked on the grounds of maintaining industrial capacity, and as discussed below, other European nations have used the exemption to place orders for similar support ships with their own shipyards since the Directive was introduced.

Were the rules tightened in 2016?

Veterans for Britain has claimed that ‘the EU tightened these rules further in 2016.’

This ‘tightening’ consists of an eight page Commission note on direct government-to-government sales. It has no relevance to the Fleet Solid Support order.

European comparisons

Other European nations have invoked Article 346 to place orders for support or auxiliary ships with their own shipyards since 2009 in procurement exercises that have not been challenged by the Commission. Italy ordered a logistical support ship from domestic suppliers under the Article 346 exemption in 2015, and other examples of post-2009 Article 346 engagements include logistical or auxiliary aircraft orders ( Table 25 ).

It should be noted that that – contrary to any impression that the EU imposes a restricted and closely-monitored regime on engagement of Article 346 – Member States are not required to inform the Commission when they exempt competitions under the Article, and the EU does not hold statistical information on the true extent of its usage.

The extent of the UK’s tendering under the Directive is also an outlier compared to other European nations. Half of all contracts by value advertised under the Directive are from the UK, according to the Commission’s implementation report . 17.7 per cent of the UK’s defence expenditure is placed under the Directive, compared to 10.3 per cent for France and around 1 per cent for the Netherlands, Sweden and Austria.

39 per cent of European defence manufacturers either disagree or strongly disagree with the proposition that the Defence and Security Procurement Directive has reduced the need for use of the Article 346 exemption (and only 29 per cent agreed with the proposition).

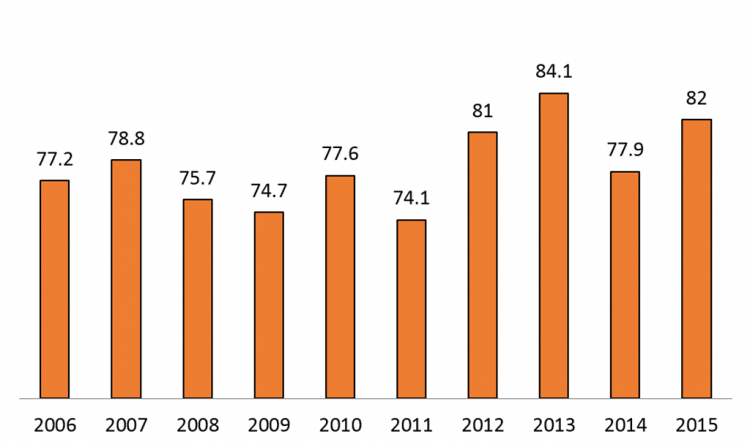

Continued preferment is also reflected in the data that is available at an aggregate level. Member States’ spending with domestic suppliers has actually gone up since the defence market was supposedly liberalised in 2009 (from 75 per cent of spending to 82 per cent).

EU Member States’ defence spending with domestic suppliers (%)

External views

The claim that the UK is barred from restricting tenders to domestic suppliers holds little water in the defence industry and the wider defence community. Chris Bovis, Professor of International Business Law at the University of Hull, recently said that:

‘If you carefully study the European directives, any government in Europe can do what they want because they have full autonomy and freedom of action in anything that relates to defence and security, which are excluded from any competitive tendering. This gives you a tremendous amount of flexibility to design a system and mechanism for defence procurement that ensures shared risk while maintaining total control.’

Conclusion

European rules regarding defence procurement have changed in the last decade, but the core exemption to international competitive tendering requirements remains in place.

In fact, the only barrier to placing the Fleet Solid Support order with UK yards is one of political will.

Italy has successfully employed the exemption to place an order for a similar logistical vessel under the exemption in recent years, and spending with domestic suppliers has actually increased since the new Directive was introduced.

Jobs are under threat at UK shipyards now. The industry’s ageing workforce, skills gaps and restricted capacity poses real threats to our ability to rebuild and replenish the Royal Navy and the Royal Fleet Auxiliary. 6,700 jobs could be created or secured in the UK, including 1,800 in shipyards, if the Fleet Solid Support order was secured in the UK.

There is still time for the government to reverse its policy of putting this order out to full international tender. Defence jobs need to be part of a long-term UK strategy that looks at our industrial needs over the long term, and how we can build the capacity to fulfil them. Keeping the vital skills in our shipbuilding industry should be part of that – and unions will continue to campaign ensure that the Fleet Solid Support vessels are built in the UK.

Further reading

GMB Turning the Tide: Rebuilding the UK’s defence shipbuilding industry and the Fleet Solid Support Order , April 2018

CSEU Fleet Support Ships: Supporting the Royal Navy, supporting the United Kingdom , May 2018

Save the Royal Navy Why the Fleet Solid Support ships should be built in the UK , January 2018

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox