High rejection rates show the self-isolation payment scheme isn’t fit for purpose

It’s clear that the scheme is one of the key failures in the government’s response to the pandemic.

The government must urgently do now what it should’ve done last March: raise and expand statutory sick pay (SSP) to ensure decent sick pay for all.

What is the scheme?

Low and patchy sick pay coverage was a problem for the UK before the pandemic began, but the crisis has highlighted the issue. Around a quarter of workers receive SSP, which is just £95.85 a week. This is bad by international standards, with the UK having the least generous mandatory paid sick leave of any OECD country.

And it doesn’t cover all workers. 2 million employees miss out due to earning less than £120 a week, and self-employed workers are not eligible.

The self isolation payment scheme was introduced to try to address this problem of low or non-existent sick pay for millions of workers and ensure everyone can afford to self-isolate.

Introduced in England on 28 September 2020, six months into the pandemic, the scheme is split in two:

-

Main scheme: eligibility is criteria set by government, aimed at workers who receive benefits, have been told to self-isolate and cannot work from home. Analysis by Resolution Foundation found that only 1-in-8 workers are eligible for this payment

-

Discretionary scheme: councils have more control over the eligibility criteria, but the intention is for the scheme to catch those who just miss out on the main payment

Councils were required to set up, run and advertise the new scheme at short notice. Initial funding of £50 million was provided, with:

-

£25 million for the main scheme

-

£15 million for the discretionary scheme

-

£10 million for setting up and administering the scheme

This funding covered the period until January 31st 2021, when the scheme was set to end. Councils were told that any overspend on the main scheme would be covered by government, but that funding for the discretionary scheme was fixed and limited.

Councils therefore set their discretionary scheme criteria knowing funding had to last for over three months. If it ran out, it was gone. No further help. This promoted caution when setting eligibility criteria, with fears that a spike in local cases could close the scheme.

Rejected applications

In early January, we sent freedom of information requests to each of the 314 English councils administering the scheme to find out how it was going as of 6th January 2021.

We heard back from 233 (74%) councils. The responses painted a clear picture of a failed scheme.

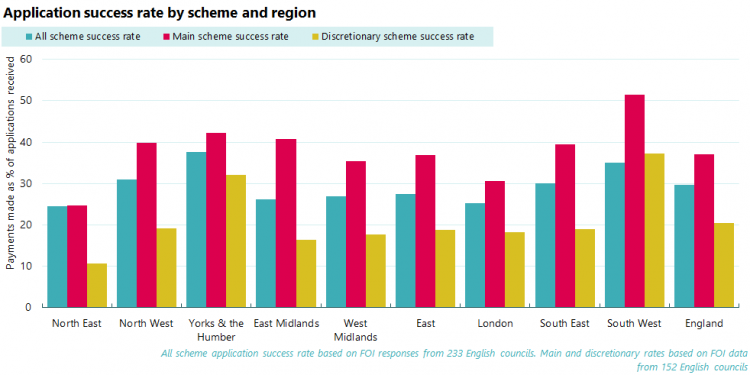

Across these 233 councils, only 30% of applications had resulted in a payment. 152 councils provided a breakdown of applications by main and discretionary schemes. For the main scheme, the success rate was 37%. For the discretionary scheme, just 1 in 5 applications had been successful.

The broad national figures disguise the extent to which the success of applications varies by regions and councils.

In a quarter of councils, just 10% of discretionary applications were accepted. In some areas, only 1 or 2% discretionary applications were accepted. Milton Keynes, for example, had received 468 discretionary applications and made just 4 payments. Derbyshire Dales had made just 1 discretionary payment, but had received 132 payments.

Lack of funding

Despite so few discretionary applications being accepted, many councils still faced funding issues.

235 councils told us about their discretionary funding. As of 6th January, a quarter of councils (26%) had run out, or were close to running out, of discretionary funding.

This left some councils having to plug the funding gap themselves.

In early January, for example, Wakefield had already spent twice the allocated discretionary funding and was using its own money for payments. Others, such as Somerset West and Taunton and Reigate and Banstead, had no choice but to temporarily close the discretionary scheme until new funding was announced.

New funding was eventually announced in mid-January. Both the main and discretionary schemes have been extended until the end of March, with £20 million extra provided to councils.

This, however, is merely an extension of a failed scheme. The slight increase in funding over the next two months may keep the scheme going, but it won’t significantly improve it.

Decent sick pay for all

The flaws of the scheme reflect the government’s unwillingness to make significant and lasting improvements to the existing safety net in response to the pandemic.

Rather than do what’s needed and increase and expand SSP last March, the government introduced a late, inadequate and under-funded short-term fix to our sick pay problem.

It must now act urgently to resolve this by increasing weekly SSP to the equivalent of a real living wage and making it available to all.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox