Five reasons why another financial crisis could be looming

While Westminster is absorbed with Brexit, alarm bells are sounding in financial markets about the impact of central bank actions on soaring private debt.

The economic forecast has been looking gloomy for some time, but last week the IMF warned that “an economic downturn lurks somewhere over the horizon”.

Unfortunately, while workers have endured a lost decade since the 2008 financial crisis, the economy has not been repaired in that time.

So without decisive action – and soon – there are five reasons why we should fear another global recession.

1. Financial markets are falling

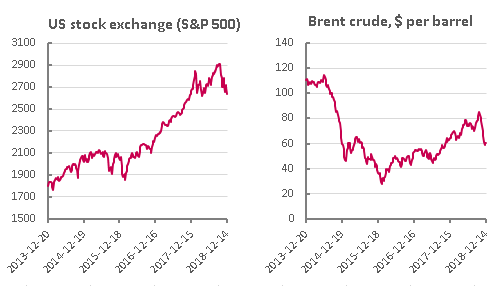

2018 has been a challenging year in financial markets, with stock exchange falls in emerging economies spreading across the world.

Last Friday the US S&P500 was down 9.5% on its September peak and the UK FTSE was trading at a two-year low.

A month ago, commentators were worrying about an oil price of $90, but today it’s now hovering around $60.

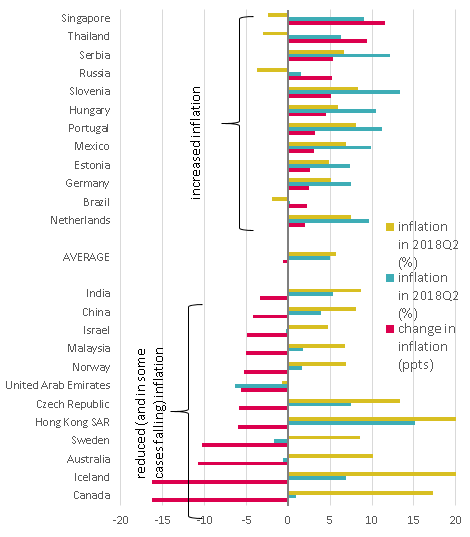

On top of this, new statistics from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS: the central bank for central banks) suggest global house prices are on the slide, as the following chart of the highest and lowest changes in house price inflation shows:

2. Debt is rising

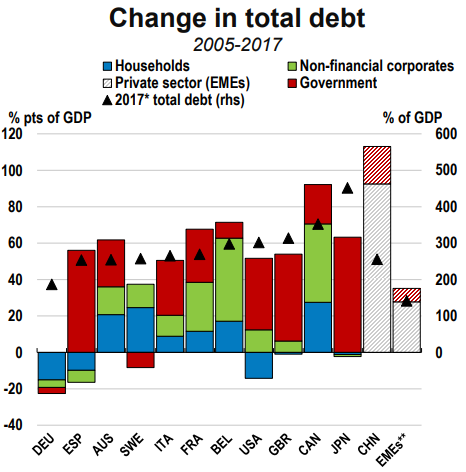

The 2008 crash showed what can happen when debt levels get out of control. And debt is now more out of control than ever.

In its November report, the OECD sounded the alarm on this with a warning that “vulnerabilities […] persist in many economies from elevated asset prices and high debt levels”.

Their September chart shows big increases in debt since the crisis – across both advanced and emerging economies and in the private and public sectors alike:

We can see that Japan and Canada are world leaders (triangles), with China catching up fast (columns). And that, overall, high debt levels have become the norm the world over.

It’s also important to consider the overlap between countries where debt is rising and where house prices are falling.

And the latest report from the Bank of England (BoE) on financial stability (largely overshadowed by Brexit) suggests three things we need to be especially worried about:

Emerging Market Economy (EME) debt

This threatens individual economies and the Western institutions that have lent hand over fist to overseas companies. The BoE estimates UK exposure to “non-China EMEs” at a colossal £575bn, warning of “material” risks to UK financial stability.

Corporate debt

The BoE shows lending to potentially vulnerable firms is at pre-crisis levels, noting that it “has reached a scale comparable to subprime mortgages on the eve of the global financial crisis”.

Shadow banking

or new institutions evolving under the radar of official scrutiny. Yannis Varoufakis reckons that this “risk has not been diminished but hidden out of sight.” But worryingly, all the Bank has to say is that “more comprehensive and consistent monitoring by authorities of the risks from leverage is needed”.

We know from the past that whenever the financial tide turns, high private debt puts pressure on firms to make cost savings. Those that are borrowing to stay afloat will go under – and that means job losses for ordinary workers.

3. The real economy is weakening

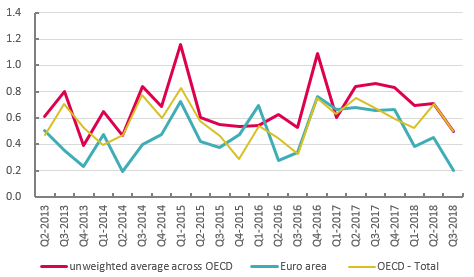

The OECD is clear that economic growth has peaked, as the following chart shows:

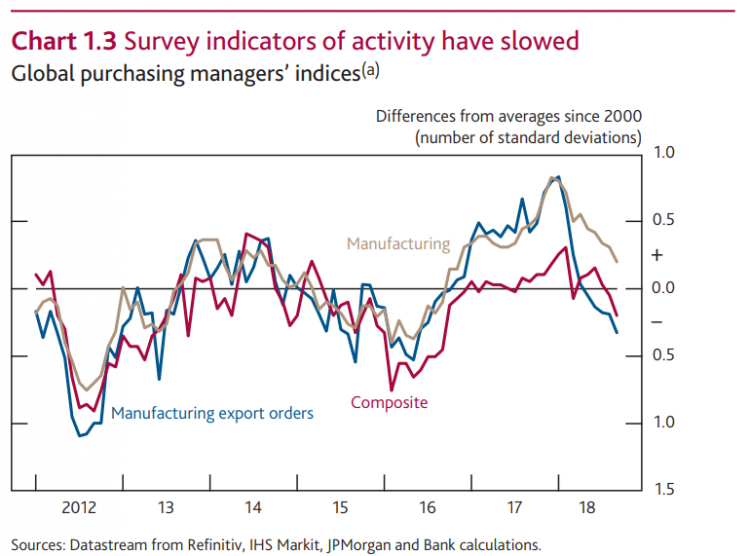

Of the emerging economies Argentina and South Africa are in decline, Turkey is expected to follow. GDP in both Germany and Japan fell in 2018Q3. And global confidence is deteriorating fast, as the following BoE chart shows:

We can see the effects of this on UK GDP growth, which has been erratic through 2018 –not to mention stagnant since August according to last week’s monthly indicator.

The best the OECD can offer is a global economy that “looks set for a soft landing”. But “downside risks abound”.

4. Policy choices are making things worse

Over the past year central bankers have called time on supporting the economy, and have reverted to the usual preoccupation with inflation and so higher interest rates and ‘quantitative tightening’.

There’s two big problems with this strategy. First there’s no sign that inflation is rising.

For example, OECD wage growth over the latest quarter may be at a post-crisis peak, but at 3% this still falls far short of what should normally be expected (and vastly short of what is needed to make up lost ground).

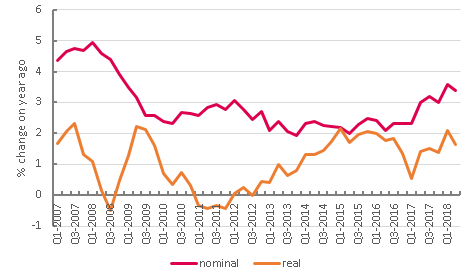

Overall, real wages are up only 1.7% since the crash – and they’re weakening, as the following chart shows:

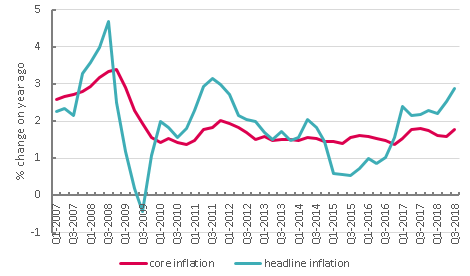

And inflation itself is still extremely low. Headline figures may have picked up a little following earlier rises in oil prices, but the underlying core rate is comfortably below 2%:

Second: interest rate rises are contributing to the world’s debt problems.

Higher U.S. interest rates mean the dollar – the world’s main currency – is more expensive.

This is making it harder for companies and governments to pay any dollar debts, triggering “ sudden changes in market sentiment ” towards emerging-market economies and capital outflows according to the OECD.

And as financial markets stop taking risks, the same thing will happen to companies and households with high debts in advanced economies.

The bottom line is a wider failure of policy since the financial crisis.

5. Lessons from 2008 still haven’t been learned

Workers are all too familiar with the disastrous impact that years of austerity have had on growth and wages.

But this has not stopped footloose investors from ploughing capital into emerging economies and trendy global tech and property ventures.

Now, as capital retreats and asset values fall, firms are facing a new round of severe financial pressures that will bear down on costs and ultimately on workers’ pay, conditions and jobs. There are also concerns that pensions are in the firing line, as funds have become seriously exposed to risk.

It all amounts to very little change ten years on from the financial crisis.

The OECD (and even two ex- BoE deputies) has already called for internationally-coordinated government spending in the event of a crisis. And we’re clear that a halt on rate rises is no less urgent. Last week the ECB (bizarrely) confirmed ‘quantitative tightening’ in spite of recognising increasing risks and conversely the Federal Reserve made backtracking noises.

But above all global action is needed to address the cause of growing debt, not just the symptoms.

The rise of nationalism has led many countries to turn inwards, blaming trade or migration for problems that are actually rooted in global financial excess.

The Great Depression eventually led to the Bretton Woods conference, when the world agreed to build a system that would contain these excesses (see our recent event on these issues).

There is a desperate need to renew this global debate before the next financial crisis arrives and workers are forced yet again to pay a price they simply cannot afford.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox