Budget 2018 - Why austerity is here to stay

The Chancellor wants you to think yesterday’s Budget was good for working people. It wasn’t.

Yes, the NHS got some much-needed additional cash, and yes, there was extra support for those transferring onto Universal Credit (although not enough to replace the £2 billion that George Osborne cut from its budget in 2015).

But there was otherwise precious little help for working people. And the biggest giveaway by far was yet another tax cut to the highest earners.

And while Mr Hammond boasted that the era of austerity was almost over, his Budget actually fell woefully short of what is actually needed to bring eight years of spending restraint to an end.

Because with real earnings remaining unchanged, there’s still no end in sight for workers enduring the longest pay squeeze in two hundred years.

Here’s what we made of Mr Hammond’s day:

Economic context

There were two conflicting forces confronting the Chancellor ahead of this Budget.

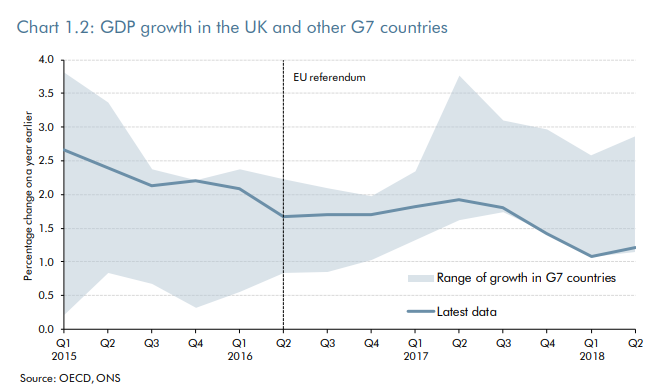

On the one hand GDP growth in 2018 has turned out even lower than expected, with the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) revising down the forecast for the year to 1.3 per cent from 1.6 per cent in the spring.

On the other, taxes have come in significantly higher than expected, meaning the forecast deficit for the current financial year 2018-19 has improved by £12billion (before any policy action).

The OBR also reminded us about how bad the UK is doing compared to other countries in the G7:

NHS spending boosts economy

The key action in the Budget was the incorporation of the Prime Minister’s pledge for £20 billion in extra funding for the NHS.

NHS spending will now rise from £7 to £27 billion over the next five years, which will outstrip the tax windfall even if it’s sustained every year.

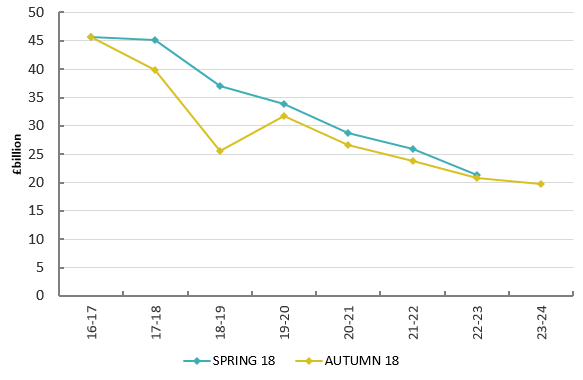

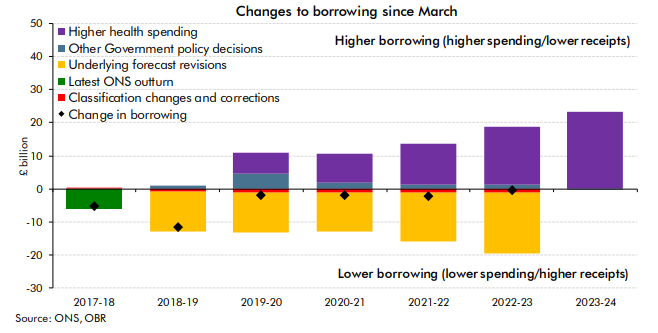

Hammond has managed to honour the NHS pledge without additional borrowing in the future, as the following chart shows:

Instead of extra borrowing, the NHS will be partly funded by a slightly improving economy.

As the following chart shows, the new NHS spending (from 2019-20 in purple) is almost exactly offset by the yellow ‘underlying forecast revisions’:

These ‘underlying forecast revisions’ can be partly explained by the OBR’s decision that “the economy can sustain lower rates of unemployment than we thought”.

This partly comes back to the dreaded ‘capacity question’.

The Treasury, Bank of England and OBR all think there are limits to the size of the economy and the rate of unemployment (and hence the options for policy action) that if breeched lead to inflation.

The OBR have now revised down the limit for unemployment four times: from 5½ % to 5% to 4½% and now to 4%.

Common sense might think it odd that policy is set against a limit that can change. The TUC position is that it’s crazy to say that the economy is hitting limits in the middle of a pay crisis. And these changes are a result of the OBR confronting reality.

With a little more capacity there is room for more growth and more revenues.

If this reality had been accepted sooner, austerity might have been reduced or understood as not necessary at all.

Austerity has failed

The Chancellor claimed that his extra spending was down to the success of austerity. In fact it was an admission of its failure.

Because the logic of his argument was that spending strengthens the economy and boosts the public sector finances – the very opposite of austerity.

That’s why austerity is a false economy. Over the last eight years, the policies of austerity have vandalised public services, damaged growth and reduced the deficit at a snail’s pace.

That’s why reversing austerity is the right policy.

Spending when the economy is weak would have repaired the public finances quicker.

And the strength of public services goes hand in hand with the strength of the economy.

Wages and public services still in crisis

For workers this is all far too little far too late.

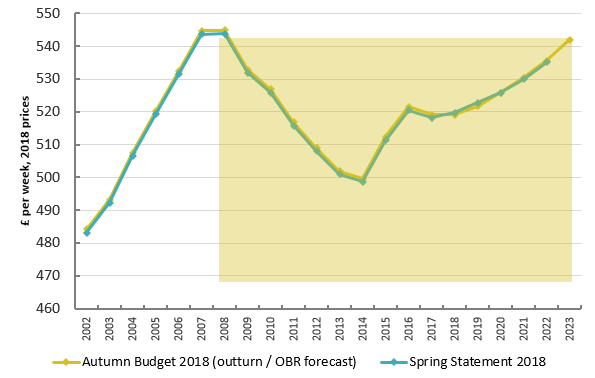

According to the OBR, any improved outlook for growth will lead to more jobs, but do nothing for real wages, as the next chart shows very clearly:

Adding a year to the forecast (2023) still doesn’t restore the pre-crisis peak. It may come in 2024, but this is far from certain.

The Chancellor attempted to soften the blow on wages with changes to tax thresholds amounting to £130 a year for most workers.

This hardly compensates for wages in 2018, which are down £26 a week or £1350 a year on the pre-crisis peak.

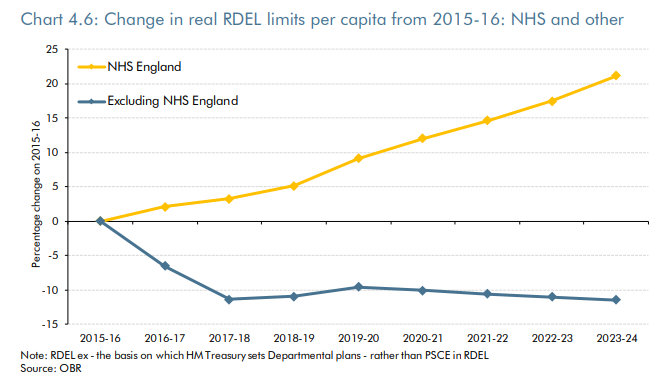

On public services, cuts across the public sector remain firmly in place outside the NHS, as the OBR’s chart on real departmental spending (‘RDEL’) per head shows:

While health spending is set to rise, severe cuts to all other public sector spending will remain in place.

This is very far from ending austerity – and the 2015 starting point in this chart omits the brutality of the cuts imposed by Hammond’s predecessor in the previous five years.

Analysis by the New Economics Foundation suggests that there will still be cuts of almost £3.5bn (5.2%) to unprotected budgets after 2020.

Even in departments with excepted protections there will be cuts per head, for example on schools – assuming protection is maintained in real terms the schools funding announced at the budget yesterday will still amount to a 2.6% cut per pupil.”

Austerity isn’t over

It’s clear that both workers and public services will continue to be pummelled by austerity policies for years to come.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. As the spending and OBR forecast shows, there is an alternative model.

Yet the OBR continues to apply the logic of the household budget, keeping improvements in the economy separate from changes in the public finances.

But managing national finances is not the same as managing a household Budget. It’s about time that the OBR and the government acknowledged this and increased public spending accordingly to set the economy on the right track.

In the meantime, austerity continues. How much longer must workers wait for it to end?

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox