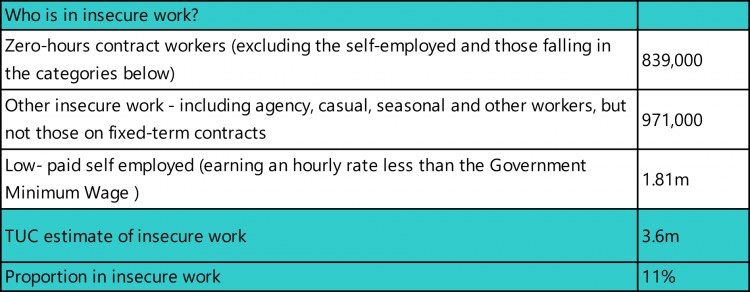

With 3.6 million in insecure work, we have an opportunity for change

TUC analysis has revealed that 3.6 million people - one in nine workers - were in insecure work ahead of the Covid-19 outbreak, leaving them exposed to massive drops in income or unsafe working conditions when the pandemic hit.

As the UK gradually returns to normality, it is crucial that we take the opportunity to embed decent work in our economic recovery, taking the opportunity presented by the forthcoming Employment Bill.

Our figures, based on official data and published in our report Insecure work: Why decent work needs to be at the heart of the UK’s recovery from coronavirus, show that insecure work is not evenly distributed, it is concentrated in occupations such as caring and leisure.

This matters because those in insecure work often don’t know what hours they will work (causing chaos with arrangements like childcare) or whether they will be able to pay their bills.

Shifts can suddenly dry up when the business sees demand dip, as experienced by so many workers in sectors like hospitality.

Insecure work can affect workers’ safety as seen during the recent Covid-19 outbreak in Leicester which was blamed on poor conditions experienced by vulnerable workers in the garment industry.

Insecure work is also bad for the economy, with clear evidence that decent work leads to better economic outcomes.

Greater security for workers would mean a stronger recovery.

To begin to deliver this, we need:

- the effective abolition of zero-hours contracts through a right to request a regular hours contract, decent notice of shifts and compensation for cancelled shifts

- penalties for employers who mislead people about their employment status and protections for the genuinely self-employed

- workers to have the right to challenge their employer over minimum wage, sick pay and holiday pay abuses

- genuine two-way flexibility, giving workers a default right to work flexibly from the first day in the job, and all jobs to be advertised as flexible

Who is in insecure work?

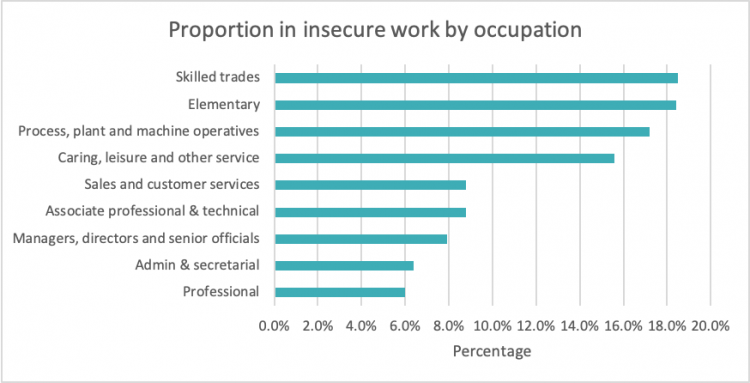

Occupation

Insecure work isn’t just found among the food delivery riders and taxi-drivers of the new app-based platform economy, who are prominent in discussions of the topic.

Key workers such as as carers, delivery drivers and shopworkers, whose value to society was brought sharply to attention during the pandemic, also suffer from it.

For example, nearly one in six (15.6 per cent) of those in caring, leisure and other service roles were in insecure work, according to our analysis of official figures.

This compares to 6 per cent of those in professional roles and 6.4 per cent of those in administrative or secretarial jobs.

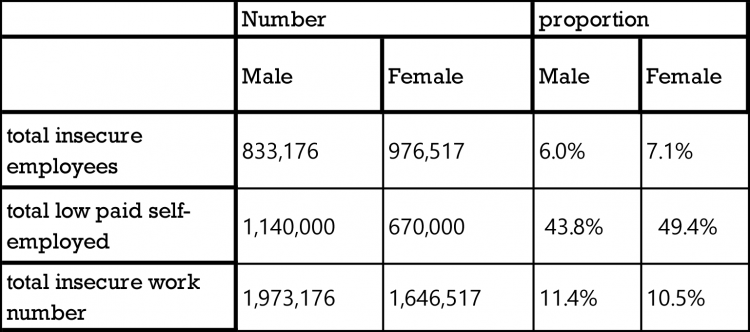

Gender

Patterns of insecurity vary significantly according to gender.

Women are more likely to be in insecure work where they are employees - with 7.1 per cent of women in this type of insecure work compared to 6 per cent of men.

The numbers of men in low paid self-employment, those earning less than the minimum wage, are almost double compared to women. However, the proportion of women who are in low paid self- employment is higher, 49.4 percent compared to 43.8 percent.

This means that, overall, 11.4 per cent of men are in insecure work, compared to 10.4 per cent of women.

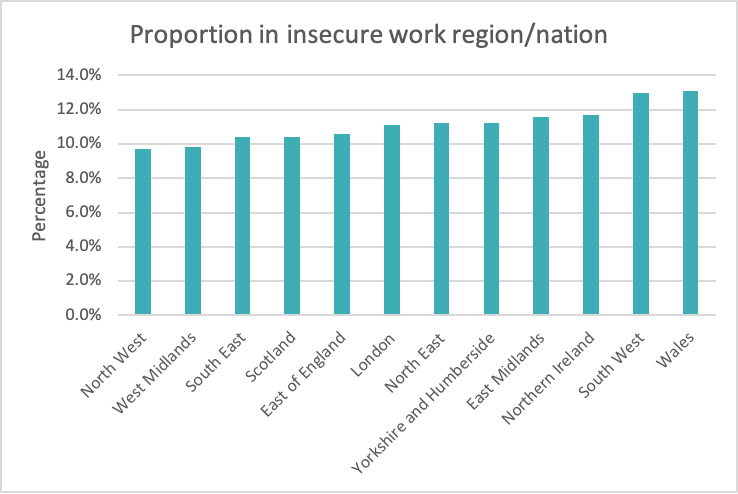

Regions and nations

A significant number of workers are in insecure work in every region of England and Wales, and in Scotland.

It is particularly prevalent in the South West of England (13 per cent) and in Wales (13.1 per cent).

The north west of England and the West Midlands fare better, but still nearly one in ten workers are in some form of insecure work.

Upcoming TUC work will look at how discrimination against Black workers plays out in the forms of insecure work they are likely to undertake.

Opportunity for change

The pandemic altered what worthwhile work looks like for many people.

Roles that had long been overlooked and underpaid - shopworkers, delivery drivers, home carers, nurses and school staff - were recognised as crucial to the functioning of a country in lockdown.

Improving job quality is not something that can wait until the economy has picked up again.

Using the Employment Bill to put these measures in place would remove some of the worst elements of insecure work.

But to ensure workers can enforce their rights and sustain progress, the positive role that unions have played during the pandemic, both in the workplace and in wider economic life, must continue.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox