Denied and discriminated against

Government

The government’s proposals in their latest consultation on flexible working fall far short of their aim of making flexible working the default.

To unlock the flexibility in all jobs and for all workers the government should introduce:

- a legal duty on employers to consider which flexible working arrangements are available in a role and publish these in job advertisements, with the new postholder having a day one right to take up the flexible working arrangements that have been advertised. If an employer does not think that any flexible working arrangements are possible, they should be required to set out the exceptional circumstances that justify this decision.

- a day-one right to request flexible working for all workers, with the criteria for rejection mirroring the exceptional circumstances set out above. Workers should have a right to appeal and no restrictions on the number of flexible working requests made.

Employers

Employers do not need to wait for legislative change in making genuine flexible work the default in their workplaces and ensuring that all workers have the opportunity to benefit from positive flexibility that helps them to balance work and home life.

Employers should include the specific types of flexibility available in job adverts with the postholder being able to take this up on the first day of the job.

In our ‘Future of flexible working’ report, we have published a set of principles that employers should follow when implementing flexible working. These include important measures to ensure flexible working becomes the norm for all workers, tackle negative workplace cultures and stereotyped attitudes towards flexible working and ensure that those who work flexibly are not disadvantaged or discriminated against.

Employers should monitor the implementation of flexible working to ensure it is promoting equality. This may be particularly important for employers introducing hybrid ways of working following the pandemic, as research suggests blanket approaches can lead negative impacts for women.

Trade unions

Trade unions should:

- work with employers to review flexible working policies and practices and should negotiate for increased access to flexible working and for the protections outlined in our principles. Trade unions are best placed to ensure the needs of employers and preferences of staff are reconciled through constructive dialogue and negotiation.

- train reps in negotiating for flexible work policies and supporting members with flexible working requests. Unions should train reps in organising hybrid workforces, where members may be spread across different locations and working different hours.

- monitor the impact of flexible working and negotiate for any necessary changes in the future.

For more detail on our recommendations on flexible working, see our Future of flexible working report.

Executive summary

The experience of the pandemic has significantly changed the landscape of flexible working. The numbers of people who worked from home during the Covid-19 pandemic (around one third of the workforce)[1] and unequal access to other types of flexible working for those who cannot has sparked public conversations about what the future of work should look like, including where, how and when we work.[2]

Flexible working is any type of work arrangement that gives flexibility in how long, where and when people work. It includes flexi-time, remote and home working, mutually agreed-predictable hours and compressed hours.

Making flexible working available in all but the most exceptional of circumstances is essential for promoting greater gender equality. Research has shown that many of the underlying causes of the gender pay gap are connected to a lack of quality jobs offering flexible work.[3] Due to the unequal division of unpaid care and the lack of flexible working in jobs, women often end up in part-time work. 75 per cent of part-time workers are women and are paid less than full-time workers with equivalent qualifications.[4] Making flexible working the norm and available to all workers, including working dads, will help to equalise caring responsibilities allowing dads to spend more time with their families as well as tackle the discrimination women face at work.[5] Action to address gender inequality is even more urgently needed given the impact of the pandemic on women.[6]

Genuine flexible working can be a win-win arrangement for both workers and employers. Employers’ groups have emphasised the extensive business benefits of flexible working, including improved recruitment and retention of workers.[7]

The government has publicly promoted the benefits of flexible work stating it leads to more productive businesses and a more engaged workforce and acknowledged the importance of flexible working as part of its ambition to build back better after the pandemic.[8] However, these messages have been undermined by damaging comments from government minsters which reinforce the same negative stereotypes of flexible workers revealed in our research.[9]

The TUC’s previous polling also shows that it is hugely popular amongst working people.[10]

Unfortunately, despite this almost universal support, many workers are still unable to access genuine flexible working.

Working mums’ experience both of trying to access flexible working and of working flexibly is shaped by negative and discriminatory workplace cultures. These cultures put many off asking for the flexible working they need; when they do ask they are frequently turned down and those who work flexibly experience discrimination and disadvantage as a result. Our survey reveals that:

The current system is broken

Working mums fear discrimination if they ask about flexible working in job interviews…

More than two in five (42 per cent) working mums who responded to our survey would not feel comfortable asking about flexible working in a job interview, mainly because they think they would be discriminated against and rejected. Only 37 per cent said they would feel comfortable raising this.

Research shows that only two in 10 jobs are currently advertised as flexible, leaving women in an impossible situation where they don’t know what flexible working is available but understandably feel reluctant to ask before they have been appointed.[11]

…and also when in work

When asked if they had requested flexible working at their current place of employment – 31 per cent had not and 36 per cent had only asked for some of the flexible working they need.

More than four in ten of those who hadn’t asked were put off by worries about their employers’ negative reaction (42 per cent) or because they thought the request would be turned down (42 per cent). Only one in 20 (5 per cent) working mums who hadn’t made a flexible working request said it was because they didn’t need it.

Similar concerns affected those who only asked for some of the flexible working they needed. Nearly three in four said the reason they did not request everything they needed was because they believed the request would be turned down (73 per cent) and half (50 per cent) were put off by worries about harm to future career prospects.

Employers are denying requests

Working mums fears of being turned down are not unfounded. Half (50 per cent) of working mums in our survey said their current employer had rejected or only accepted part of their flexible working request. Given that more than a third of mums (36 per cent) only asked for some of the flexible working they needed, a partial acceptance could leave them a long way away from the flexible working arrangements they truly need.

Most mums who work flexibly experience discrimination and disadvantage

Negative workplace cultures and stereotyped perceptions of flexible working also shape the experiences of those mums who of work flexibly. 86 per cent of mums in our survey who worked flexibly told us they had experienced discrimination and disadvantage as a direct result of this.

Flexible working isn’t just a ‘nice to have’

Our survey shows that women need flexible working to be able to work. More than nine in 10 (92 per cent) mums who worked flexibly told us they would find it difficult or impossible to do their job without it.

This means if flexibility is not included in job adverts, many women will feel locked out of applying, curtailing their access to a wide range of jobs. Almost all of the working mums (99 per cent) in our survey said they would be more likely to apply for a job if it included the specific types of flexible working available in the advert.

There is overwhelming support for the solutions that will genuinely make flexible working the default

On 23 September, the government announced a consultation on new proposals that claim to deliver on their manifesto promise to make flexible working the default. However, the proposals, offering minor tweaks to a failed system, fall short of delivering on the government’s ambition. The consultation focuses on slightly adjusting the law so that employees can make a flexible working request from day one of the job rather than having to wait 26 weeks as employees do now. They reject the need to include flexible working options in jobs adverts and do not put forward proposals around the need to tighten the criteria for rejecting requests.

The TUC believes in order to actually make flexible working the default, which working mums so desperately need, and meaningfully promote gender equality, any policy change will need to address the barriers women face at recruitment, in having requests accepted and remove the stigma attached to flexible working.

This can be done by ensuring employers proactively consider the range of flexible working options available in different job roles, include these in job adverts, so women are clear about what flexibility is available and ensure workers have access to flexible working in all but exceptional circumstances.

Our survey reveals overwhelming support for these steps that will truly make flexible working the default:

· 99 per cent of working mums who responded to our survey think that the government should create a new duty on employers to advertise flexible working in job ads with the successful candidate having the right to take up the advertised flexibility.

· 96 per cent think that government should give all workers the right to flexible working from day one in the job, not just the right to ask.

If the government genuinely wants to make flexible working the default, we cannot continue to rely on a system based on individuals asking nicely and hoping for the best. A system based on an individual’s weak right to request drives approaches where flexible working is seen as a limited resource, doled out sparingly as a perk, rather than the norm. It does nothing to change workplace cultures where attitudes to flexible work are shaped by longstanding sexist stereotypes. The government’s approach, which just offers more of the same approach, will mean that women continue to lose out.

It is also becoming increasingly clear that we cannot rely on the changes brought about by the pandemic to shift employer’s attitudes and practice around flexible working in the long term. Evidence shows us that despite the huge amount of media attention dedicated to working from home, access to flexible working is not actually increasing for many workers. CIPD research shows a drop in all forms of flexible working (other than homeworking) since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.[12] And even just looking at working from home, the number of jobs advertised as open to remote working dropped by 24 per cent between June and August of this year.[13] One in six (16 per cent) working mums in our survey also told us they had been forced to return to their workplace fulltime since working from home guidance had lifted.

The government consultation and eagerly awaited Employment Bill offer a real opportunity to deliver the change needed to unlock the flexible working opportunities contained in all job roles and to make genuine flexible working the norm. This would transform the working lives of working mothers across the country. A failure to act would be a betrayal of these women and a tacit acceptance of widespread discrimination which shapes their working lives.

Background

What is flexible working?

Flexible working is any type of work arrangement that gives flexibility in how long, where and when people work. It can include:

· part-time working

· mutually agreed, predictable hours, for example agreed shift patterns

· varying start, finish and break times

· flexitime

· compressed hours, for example working the same amount of hours every week but over fewer days

· homeworking or work at another remote location

· job-shares

· term-time only working or different hours during the holidays

· phased retirement

· annualised hours, for example, working a set number of hours over a year with control over when you work them.

Not all jobs can support every type of flexibility, but every job can accommodate some kind of flexible working.

What rights do workers currently have?

Workers in the UK do not currently have a right to work flexibly, they merely have a right to request it. This right to request flexible working has existed in some form or other for almost two decades. It was originally introduced in April 2003 for parents of children aged under six (or under 18 if disabled). This followed a report by the Work and Parents Taskforce which found that if there was no intervention parents might drop out of the labour market.[15] The right to request was characterised at the time as a “gentle push towards policies that would otherwise take 20 years to achieve”.[16] Since that point, the legislation has been incrementally widened until 2014, when all employees with at least 26 weeks' continuous employment, regardless of parental or caring responsibilities, were able to request flexible working arrangements. Only those legally classed as employees are able to make requests and only one request every 12 months is permitted.[17]

The impact of the right to request

The current system is broken:

It’s too easy for employers to turn down requests

Employers currently have an almost unfettered ability to turn down a flexible working request, given the breadth of the eight statutory “business reasons”[18] that can currently be used to justify a refusal.

TUC research in 2019 showed that three in 10 flexible working requests are denied and that flexi-time (the most popular form of flexible working) was unavailable to over half (58 per cent) of the UK workforce, rising to nearly two-thirds (64 per cent) for people in working-class occupations.[19]

Employees also have no legal right to appeal an employer’s decision once it has been made and employers can take up to three months to respond to a flexible working request meaning employees often wait weeks or months before receiving a response.

Negative workplace cultures put workers off asking

There is a stigma that has been attached to flexible working, largely because of its association with women seeking to balance work and caring commitments.[20] Research conducted by BEIS and EHRC[21] in 2016 found that nearly two in five (38 per cent) mothers did not request the flexible working they wanted, typically because they did not think it would be approved or because they were worried their employer would view their request negatively.

Flexible work is stigmatised as it’s not the default

Women who work flexibly are likely to experience negative treatment as a result. The same study by BEIS and the EHRC revealed that over half (51 per cent) of mothers had experienced discrimination or disadvantage as a direct result of having a flexible working request approved. This included receiving fewer opportunities than other colleagues at the same level, receiving negative comments from their employer or colleagues and being given more junior tasks than previously. Working mums reported feeling they had to ‘pay a price’ of being undervalued, demoted and side-lined in order to access the flexibility they needed.

Other research also suggests that the stigma related to flexible working is highly gendered and rooted in sexist views of working mums’ commitment to their jobs.[22]

It’s not leading to an increase in access to flexible working

Finally, despite the length of time legislation has been in place and the incremental broadening of its scope, it has not brought about the changes intended. The proportion of employees doing no form of flexible working (under the Labour Force Survey definition) has only changed by 4 percentage points, from 74 per cent to 70 per cent between 2013 and 2020.[23]

Additionally, there is limited evidence that after 26 weeks the number of working people accessing flexible working significantly increases. TUC analysis of the Labour Force Survey[24] shows that the percentage of employees on flexi-time (the most popular form of flexible work) with less than three months service is 9.3 per cent and only increases to 11 per cent for employees with between six months and less than 12 months service.

Our analysis suggests that the current right to request does not appear to drive a significant increase in access to flexible working, but there is more of a gradual rise, perhaps associated with seniority or trust built over time.

CIPD research also showed that despite home working rates going up, the use of flexible working hours fell over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic.[25]

Making flexible working the default

There is widespread recognition of the fact that the current legislative framework in relation to flexible working needs to be changed. The government itself highlighted this in its 2019 manifesto commitment to make flexible working the default.

The pandemic changed the way we work overnight. Legislation and accompanying guidance in response to Covid-19, meant many worked from home for the first time and workplaces had to rapidly adapt to new measures such as social distancing. Workers adapted flexibly to huge upheavals in their working lives and kept the country running. Flexibility from employers was needed to support workers to deal with home schooling and caring for loved ones who were shielding. As restrictions have been lifted, public conversations about the future of work, and increased access to flexible working, in particular home working, have become widespread.

However, although home working has been one of the dominant narratives of the pandemic it is by no means the experience of all or even a majority of workers. ONS data demonstrates that access to home working has been uneven across age, region and income level.[26] The TUC’s recent report on the future of flexible working, highlighted the real risk of a class and geographical divide being created between the flexible working have and have nots if the government does not take action to ensure genuine flexible working is available to everyone.[27]

The government has finally begun to act on its 2019 manifesto pledge and published a consultation on making flexible working the default.[28] The consultation contains proposals to reform flexible working legislation and it considers:

· allowing employees to ask for flexible working from their first day in a job

· whether the eight business reasons for refusing a request all remain valid

· requiring an employer to suggest alternatives if flexible working requests are denied

· if the limits on the number of requests that can be made remain appropriate and if the length of time employers have to respond to a request should be changed

· requesting temporary arrangements.

The consultation recognises the benefits flexible working can bring to both workers and employers, and that flexible working must form part of the government’s efforts to build back better after the Covid-19 pandemic. However, our survey findings demonstrate clearly these changes fall far short of what is needed to making flexible working genuinely the default.

Key findings

Is the right to request working for working mums?

Our survey results from 12,859 working mums show the current legislation on flexible working is not working for them in a range of ways.

Working mums won’t ask about flexible working in job interviews…

More than four in 10 women respondents to our survey (42 per cent) stated they would not feel comfortable asking about flexible working in a job interview, mainly because they thought it would be held against them by the employer, leading to them being automatically rejected. Only 37 per cent said they would feel comfortable raising this.

A number of respondents stressed the highly gendered nature of these stereotypes:

> “I have found that particularly a woman asking for flexible working automatically makes many employers concerned about your commitment and the possibility that you may not work as hard as other candidates. Unfairly I should add!”

Woman working in the public sector with flexi-time and remote working

> “There is still stigma that flexible working is for mums who aren't as committed to their job.”

Woman in the third sector with no flexible working

> “Most places make it very awkward when discussing flexible working and generally are less likely to choose you if you need flexible work.”

Woman in the public sector with remote working

> “The employer is more likely to question your commitment to the organisation. Unless it’s proactively raised or an organisation is known for their flexible working I would not raise it”

Woman in the private sector with flexi-time and remote working

Research shows that only two in 10 jobs are currently advertised as flexible, leaving women in an impossible situation where they don’t know what flexible working is available but are understandably uncomfortable about asking before they have been appointed.[29]

…Or when in work

When asked if they had requested flexible working at their current place of employment – 31 per cent had not asked and 36 per cent had only asked for some of the flexible working they need.

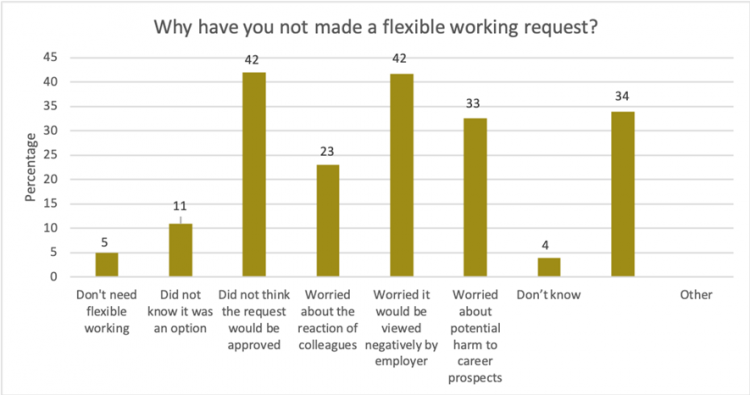

Of the women who had not requested a flexible working request, when asked why, four in ten working mums reported that they were worried it would be viewed negatively by their employer (42 per cent), and that they thought the request would be rejected so there was little point in asking (42 per cent) as shown in Figure 1. A third (33 per cent) also stated they were worried about the potential harm to future career prospects and 2 in ten were worried about the reaction of their colleagues (23 per cent). Only one in 20 (five per cent) said that the reason they didn’t ask for flexible working was because they didn’t need it.

[1]www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/labourproductivity/articles/homeworkinghoursrewardsandopportunitiesintheuk2011to2020/2021-04-19#characteristics-and-location-of-homeworkers

[7] https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/relations/flexible-working/factsheet - 6657 and https://www.zurich.co.uk/en/about-us/media-centre/company-news/2020/zur…

[12] https://www.cipd.co.uk/knowledge/fundamentals/relations/flexible-working/flexible-working-impact-covid

[20] Chung, Heejung (2020) Gender, Flexibility Stigma, and the Perceived Negative Consequences of Flexible Working in the UK. Social Indicators Research, 151 (2). pp. 521-545. ISSN 0303-8300. (doi:10.1007/s11205-018-2036-7) (KAR id:70102)

[26] https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmen… letins/coronavirusandhomeworkingintheuk/april2020

[29] https://timewise.co.uk/article/flexible-jobs-index/

Figure 1: Reasons working mums had not made a flexible working request

Similar concerns were raised by working mums who only asked for some of the flexible working they needed. Nearly three in four did not request everything they needed because they believed the request would be turned down (73 per cent) and half (50 per cent) were put off by worries about harm to future career prospects. More than 2 in 5 (42 per cent) were worried about the reactions of their colleagues.

Working mums are not requesting the flexible working they need because of fear of negative treatment or refusal.

Employers are denying requests

These fears are not unfounded but are based in the reality of women’s experiences at work.

Two thirds (67 per cent) of respondents stated they requested flexible working at their current place of employment, the most popular being part time working (46 per cent), flexi-time (36 per cent) and working from home for all or part of the week (31 per cent).

Half of working mums (50 per cent) who did ask for flexible working said their employer had rejected or only accepted part of their request. High paid women were more likely to have their flexible working request accepted in full compared to women on low pay (42 per cent for low paid women and 52 per cent for high paid women).[30] Single mums were more likely to have had their request denied (23 per cent compared to 16 per cent of those living with a partner). And Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) working mums were slightly more likely to have had a request rejected (18 per cent) compared to white respondents (16 per cent).

Given that more than a third of mums (36 per cent) only asked for some of the flexible working they needed, a partial acceptance could leave them a long way away from the flexibly arrangements they truly need.

|

A union rep working in retail told us that their employer has rejected almost all the flexible working requests made by staff. They said that accepting request would encourage others to ask for the same, which would be bad for business. One rejected request came from Rachel who asked for her late night shift to be changed to an earlier one. She had been experiencing hot flushes in the night as a result of the menopause and coupled with working back-to-back late and early morning shifts was suffering from irregular sleep. In addition, Rachel explained to her employer she was experiencing night terrors as a result of historical assault and had been advised in counselling that a regular sleep pattern would help. The request was rejected due to incompatible hours. |

Flexible workers experience discrimination and disadvantage

Furthermore, the same negative workplace cultures that mean women don’t ask for flexible working, result in women experiencing negative consequences when they do work flexibly.

More than eight in 10 (86 per cent) of mums working flexibly told us they had experienced disadvantage and discrimination as a result. This included receiving negative comments from their employer or colleagues (44 per cent), getting fewer opportunities than other colleagues at the same level (43 per cent), missing out on training opportunities (31 per cent), feeling your opinion was less valued or taken less seriously (28 per cent), being given more junior tasks than before (20 per cent) or feeling uncomfortable asking for time off or additionally flexibility (62 per cent).

Disabled women were more likely to report experiencing discrimination or disadvantage (93 per cent) compared to non-disabled women (86 per cent). Low paid women were also slightly more likely to report having experienced discrimination or disadvantage (88 per cent) compared to high paid women (84 per cent).

Our survey indicates that under the current right to request system, women do not feel able to ask for flexible working for fear of negative treatment, those who do ask are likely to be rejected in full or in part and those who manage to gain access to flexible working face high levels of discrimination and disadvantage.

How important is flexible working to working mums?

For the vast majority of women responding to our survey, flexible working is not just a nice to have or perk of the job. Nine in 10 respondents who worked flexibly (92 per cent) said that they would find it difficult or impossible to do their job without it. Almost two in three (64 per cent) stated flexible working was ‘Essential – I wouldn’t be able to do my current job without flexible working’ , with over a quarter (28 per cent) saying it was ‘Important – it would be difficult to manage my current job without flexible working’. This rose amongst low paid women– 75 per cent of whom said flexible working was essential, disabled women – 73 per cent said flexible working was essential and single mums - 70 per cent said flexible working was essential.

This means if flexibility is not included in job adverts, many women will feel locked out of applying, curtailing their access to work. Almost all of the working mums (99 per cent) in our survey said they would be more likely to apply for a job if it included the specific types of flexible working available in the advert.

The written responses provided by women show how essential flexible working is.

Working mums need flexible working to remain in work

> “I wouldn't be able to work nearly full time without flexibility”

Woman in the public sector with compressed hours and remote working

> “Flexible working has been crucial for me in my sons early years. If I wasn’t able to work part time- I would be out of the job market. Another lost skilled worker.”

Woman working part time in the private sector

> “I am currently on maternity leave and will be requesting flexible working when I intend to return in 11 months. If my employer doesn't allow this, I'll be forced to leave my role.”

Woman in the private sector with no flexible working

> “I have two children with different nursery and school drop-off and pick-up times which I cannot move. Without flexible work in my current role, I would be unable to work.”

Woman working part time in the private sector with flexi-time and remote working

Working mums need flexible working to manage childcare

Flexible working is not a substitute for a good quality, affordable childcare system; all working parents should have access to both. However, a number of respondents also stated that flexible working was important in helping to manage the high cost of childcare:

> “Childcare cost too much so between me and my husband it’s essential that we do get flexible working.”

Woman in the private sector with mutually-agreed, predictable hours

> “I cannot afford childcare. Flexible working allows me to look after my pre-school aged children and work, without this I would have to claim benefits.”

Woman working part time in the public sector with flexi-time, term-time only working and remote working

Flexible working has a positive impact on mental health

Working mums told us of the positive impact on their mental health, the time they can spend with their families and how flexible working has opened up career opportunities:

> “Being able to work flexibly gives me an essential work life balance. I feel I can have a career as well as be a mum. It’s made a huge difference to our home life and my mental health. so much so, I'm currently pregnant with my 2nd and still applying for promotion because I have the confidence I can do both.”

Woman in the public sector with flexi-time, compressed hours and remote working

> “[Flexible working means] work/life balance, reduced stress for myself and kids. Able to work and move up the ladder professionally and financially.”

Woman working part time in the public sector

|

Anne is a mortgage adviser at building society and lives with her 8-year-old son, who is autistic. When lockdown started it had a severe impact on her son’s mental health and she found play therapy to support him. But the only sessions available were on Friday afternoons and 40 minutes’ drive away. Anne’s manager suggested a flexible-hours pattern, working longer hours Monday to Thursday so that she could finish early on Fridays for the play therapy appointments. This approach was aided by changes the company made in the pandemic to enable home-working, which removed commuting time. Anne shifted her duties to do non-customer facing work early in the morning before calls started and the flexibility meant no loss in pay. Anne said told us that her flexibility has worked amazingly for her and her son. She feels like she has her son back, is able to work full-time while being a mum and still has time to train and develop. |

Women also highlighted the consequences of not getting flexible working in all jobs.

Lack of access to flexible working forces working mums into insecure work

> “It’s important that I’m able to be there for my children when they need me. I’ve had to go to a self-employed nursing role to make sure this works. By doing this though, it means I don’t get sick pay and holiday pay depends on how many shifts I’ve worked. It’s a burn-out.”

Woman working part time in the public sector

And can force them out of the labour market altogether

> “I had to give up my previous job as they didn’t want to be flexible, having children means that you can’t just work any hour they ask. It’s incredibly frustrating and soul destroying having to give up a job because you can’t look after your children.”

Woman working part time in private sector with term time only working and mutually-agreed, predictable hours

> “I have had to leave my employed role recently due to my boss shutting down my request for flexible working. It would make the world of a difference to me to have not been put in that position.”

Woman in the private sector with remote working

Women’s views on accessing flexible working in the future

If flexible working is to become the default, the negative perceptions that surround it will need to be addressed. Otherwise, we run the risk of increased levels of flexible working leading to more women being discriminated against in the workplace. Therefore, we asked women what they thought the likelihood of accessing flexible working in the future would be and what they thought their employer’s attitudes to flexible working were.

Women’s views on the likelihood of accessing different types of flexible working

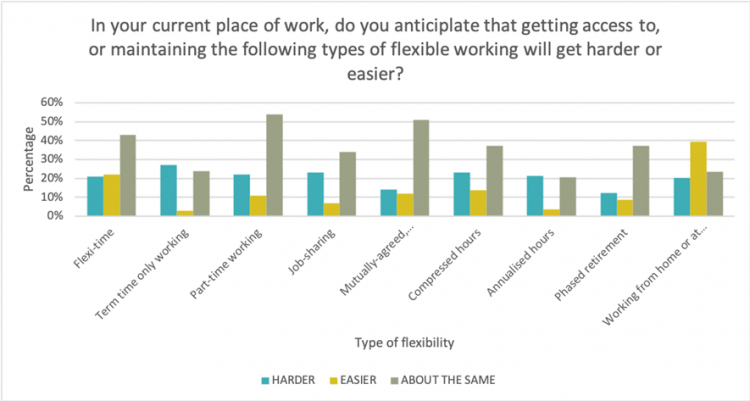

We asked working mums if they anticipated that getting access to or maintaining different types of flexible working would become harder or easier in the future.

Women’s expectations for the future demonstrate a significant minority who think getting access to flexible working in the future will become harder, as shown in graph 2. Only 22 per cent of women thought getting access to flexi-time would get easier, 11 per cent for part-time work, 8 per cent for job-sharing and 3 per cent for term time only working.

Figure 2: Working mums anticipating that getting access to or maintaining the different types of flexible working will get harder or easier.

Looking at all responses, working from home was the only type of flexible working where mums were more likely to anticipate that getting access to this in the future would be easier (20 per cent reported they anticipated it would get harder and 39 per cent reported it would get easier).

Across all types of flexible working, apart from part time working, low paid women were more likely to think it would get harder to access flexible working compared to high paid women.

Line manager and employer attitudes to flexible working

For flexible working to become the default, the negative perceptions that surround it need to be addressed. Research shows that negative views of flexible working may be rooted in gendered views society holds of mothers’ commitment to work.[31] Employers hold a central role in challenging these views by setting positive policies on flexible working to drive culture change. The role of the line manager is to translate policies into access to, and positive experiences of, flexible working.[32]

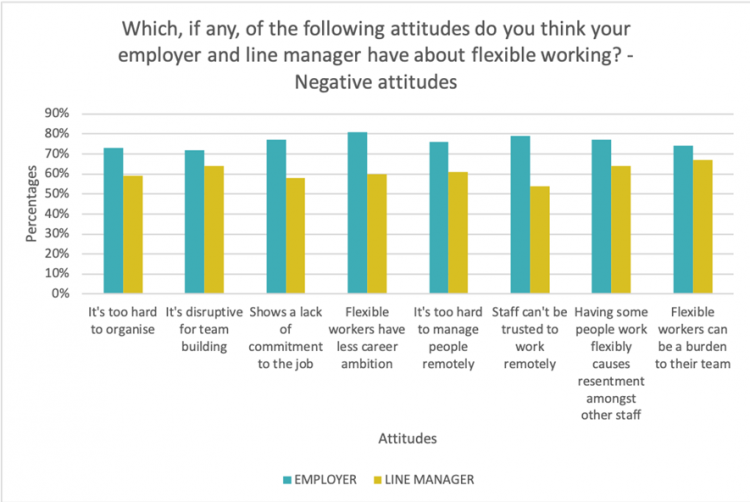

We asked women what they thought their employer and line managers attitudes to flexible working were. The majority of respondents said that both their employers and line managers had negative attitudes towards flexible working across a range of measures, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Employer and line manager negative attitudes to flexible working

Overall women were more likely to think their employer had negative attitudes compared to line managers.

Respondents told us about how they felt this lack of trust and negative attitudes towards flexible working translated into organisational practice. In particular they highlighted being required by their employer to end or limit working from home:

> “It is controlling and has no link to my productivity it seems in my case that this is about lack of trust and micromanagement from an outdated management style. The cost and amount of time travelling has doubled. There is now no work life balance which is having a huge impact mentally in a negative way.”

Women working in the private sector with no flexible working arrangements

> “There is no reason for me to work in the office full time, it is a company trust issue.”

Woman in the private sector with no flexible working arrangements

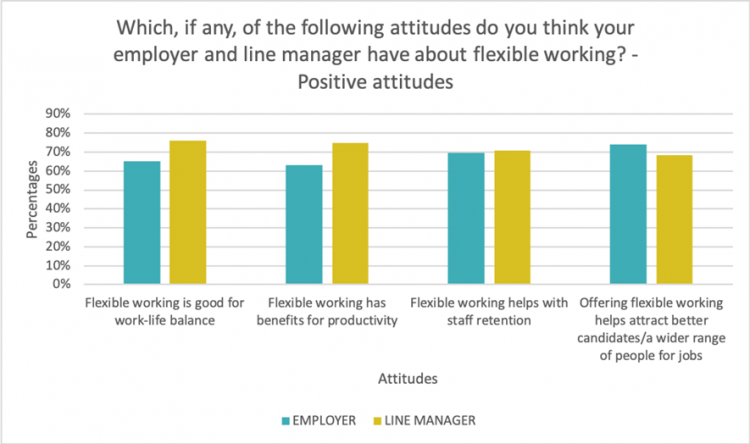

Looking at positive attitudes towards flexible working, (as shown in Figure 4) 74 per cent of working mums thought their employer believed offering flexible working helps attract better candidates and 68 per cent thought their line manager believed this. 70 per cent of women believed their employer thought flexible working helps with staff retention and 71 per cent thought that their line manager believed this.

Figure 4: Employer and line manager positive attitudes towards flexible working

These positive views are encouraging. However, they exist in stark contrast to women’s experiences of discrimination and disadvantage and barriers in accessing flexible working. We can only surmise that the negative perceptions of flexible workers that the majority of employers and line managers are reported to hold are more influential in shaping practice than the reported positive attitudes. Given the high percentages of women that believe employers and line managers hold negative views of flexible workers, any model based on employer approved requests with broad criteria for rejection is unlikely to lead to a significant rise in access to flexible working. It puts women’s participation in the labour market at the mercy of their employer’s attitudes.

Research also suggests we cannot rely on increased access to flexible working to be driven by the hope that the pandemic has changed attitudes to flexible working. The number of jobs advertised as remote dropped by 24 per cent between June and August of this year of this year.[33] CIPD research also shows a drop in all forms of flexible working (other than homeworking) since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.[34] And the barrage of negative new stories and comments from government ministers on homeworkers promote outdated and damagingly stereotyped views of flexible workers.[35]

The impact of homeworking during the pandemic

Working from home compared to working from an external workplace

We also sought to understand the difference in future expectations of accessing flexible working between women who were able to work from home during the pandemic and those who could not.

As shown in Table 1 below, women who worked from an external workplace during the pandemic were more likely to think getting access to flexible working would be harder in the future across a range of types of flexible working.

This is supported by a previous TUC survey of employers, which suggested that employers are more likely to not offer flexible work to staff who could not work from home during the pandemic.[36]

Without government intervention we therefore risk a divide where those who have worked from home (more likely to be in higher paid occupations and in certain regions of the country) are potentially more likely to be able to access flexible working in the future.[37]

The experiences of mums who worked from home

In addition, we saw a difference in attitudes towards flexible working amongst employers whose staff had been able to work from home. Half of working mums who had worked from home during the pandemic (52 per cent) had remained working from home since the government’s home working guidance ceased in England on 19 July. Just under a third (31 per cent) said they were splitting their time between home and work and 18 per cent had returned to an external workplace fulltime.

Of those who had returned to a workplace fulltime, 91 per cent had done this at the request of their employer.

When ask how satisfied they were with their current working arrangement, these women were significantly more likely than others to say they were unsatisfied (28 per cent compared to 2 per cent for working mums who had continued to work from home) and also to say they were very unsatisfied (17 per cent compared to less than 1 percent of working mums who had continued to work from home).

Those who had been asked by their employer to return to an external workplace fulltime, were consistently more likely to describe their employer as having negative attitudes towards flexible workers and less likely to have positive attitudes. For example, 84 per cent thought that their employer believed that staff can't be trusted to work remotely compared to 79 per cent of other respondents. Less than half (49 per cent) said their employer thought flexible working has benefits for productivity compared to almost two thirds (63 per cent) of other respondents.

Those who had been asked by their employer to return to an external workplace full time were also more likely to believe that getting access to different types of flexible working would become harder in the future, as demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1: Results from ‘In your current place of work, do you anticipate that getting access to, or maintaining the following types of flexible working will get harder or easier in the future?’

|

Type of flexibility |

Women anticipating it would get harder to access this flexibility (per cent) |

Women who had been asked by their employer to return to an external workplace anticipating it would get harder to access this flexibility (per cent) |

Women who worked from an external workplace during the pandemic anticipating it would get harder to access this flexibility (per cent) |

|

Flexi-time |

21 |

34 |

32 |

|

Term time only working |

27 |

25 |

31 |

|

Part-time working |

22 |

34 |

28 |

|

Job-sharing |

23 |

34 |

27 |

|

Mutually agreed predictable hours |

14 |

17 |

24 |

|

Compressed hours |

23 |

30 |

29 |

|

Annualised hours |

21 |

25 |

26 |

|

Phased retirement |

12 |

19 |

19 |

|

Working from home or at a remote location |

20 |

36 |

23 |

As we can see home working has not led to employers adopting universal positive attitudes to flexible working and is not a guarantee that workers will be able to access flexible working in the future.

Employers should not simply be forcing workers back to their previous working arrangements now that restrictions have been lifted but working with trade unions to understand how working mums would like to work in the future and negotiating new patterns of flexible working, including hybrid or remote working.

Trade unions are best placed to ensure that hybrid working works for both the employer and for workers, including working mums. Research suggests that blanket policies around hybrid work can lead negative impacts for women, so employers must ensure any new ways of working are fair and promote equality.[38]

What change do working mums want to see?

We asked women to what extent they agreed or disagreed with two proposed policy solutions for making flexible working the default. These were that:

· Government should give all workers the right to flexible working in all but exceptional circumstances.

· Government should create a duty on employers to advertise flexible working in job adverts. The successful candidate should then be able to take up the flexibility advertised

The solutions remove the onus on individuals to ask for flexibility and encourage employers to think up front about flexible working in job roles and include these in job adverts. Moving from a system based on individual requests to one where flexibility is offered in all roles will address negative cultures surrounding flexible working which are shaped by longstanding sexist stereotypes, resulting in women’s requests being denied or experiencing discrimination and disadvantage as a result of flexible working.

Making flexible working the norm and available to all workers, including working dads, will also help to equalise caring responsibilities allowing dads to spend more time with their families.[39]

These solutions will deliver meaningful change for women who have been locked out of job roles due to a lack of flexibility, and working mums support them.

Respondents to the survey voiced overwhelming support for the policy solutions that the TUC are suggesting to make flexible working the default.

· 99 per cent think that the government should create a new duty on employers to advertise flexible working in job ads with the successful candidate having the right to take up the advertised flexibility.

· 96 per cent of respondents think that government should give all workers the right to flexible working from day one in the job.

The government consultation and eagerly awaited Employment Bill offer a real opportunity to deliver the change needed to unlock the flexible working opportunities contained in all job roles and to make flexible working the norm. This would transform the working lives of working mothers across the country. A failure to act would be a betrayal of these women and a tacit acceptance of widespread discrimination which shapes their working lives.

[33] https://www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/news/articles/vacancies-remote-roles…

Methodology

The TUC ran a self-report internet survey in partnership with Mother Pukka between the 19 August and 26 September. There were 21,453 respondents. Participants were self-selecting, 98 per cent (14,242) of those who responded to the question on gender were women, and of them 12, 859 had children under 18. This report focuses on analysis of the responses from working mums to understand their experiences of flexible working.

57 per cent of working mums who responded worked in private sector, 32 per cent in the public sector and eight per cent in the third or not for profit sector.

43 per cent of mums work in permanent full-time employment, 39 per cent in part-time permanent employment with fixed hours per week, nearly six per cent are self-employed and just under five per cent of respondents are in either full time or part time fixed term contracts. Over one in three respondents (37 per cent) are key workers.

Five per cent of women are single mums.

Five per cent of working mums identified as BME.

The majority of respondents are from London and the South East (40 per cent) but we received over 1000 responses from working mums in the North West, Midlands, South West and over 500 responses from Yorkshire and Humberside, East of England and Scotland. We had over 300 responses from the North East and Wales. Regional breakdown of key statistics can be found in Appendix 1.

Two per cent of working mums reported that they considered themselves to be disabled.

We asked respondents for their annual income bracket, twelve per cent of women earned up to £15,000 per annum and twenty per cent earned more than £50,000. In this report we define low paid earners as those who earn up to £15,000 and high-paid earners as those who earn more than £50,000.

Low paid working mums were more likely to be key workers compared to high paid working mums (41 per cent compared to 19 per cent).

We have supplemented the findings with case studies gathered by union reps.

Findings in this report are taken from women. We had 270 men respond to the survey, while this is not a large enough sample to for us to feel confident in our findings, we want to acknowledge and share their responses. These are set out below.

· 47 per cent said their current employer had rejected or only accepted part of their flexible working request.

· Of those who had not requested flexible working from their current employer, 44 per cent reported they did not think the request would be approved and 54 per cent were worried it would be viewed negatively by their employer.

· 77 per cent of men working flexibly have experienced negative treatment as a result

· 24 per cent would not feel comfortable asking for flexible working in a job interview

· Around eight in 10 flexible workers (81 per cent) would find it difficult or impossible to do their job without it

· 96 per cent of men said they would be more likely to apply for a job if it included the specific types of flexible working available in the advert

· 94 per cent think that the government should give all workers the right to flexible working from day one in the job.

· 95 per cent think that the government should create a duty on employers to advertise flexible working in job adverts with the successful candidate being able to take up the flexibility advertised.

In addition to this report, the TUC will shortly be publishing a report on flexible working as a reasonable adjustment, highlighting disabled workers’ preferred working patterns and locations in the future.

Appendix 1: Regional breakdowns of key statistics

Table 2: How important is your flexible working arrangement

Percentage of working mums who work flexibility who would find it difficult or impossible to do their job without it.

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

92 |

89 |

90 |

92 |

94 |

93 |

93 |

Table 3: Employers response to flexible working requests

Percentage of working mums whose flexible working request was rejected or only partly accepted.

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

55 |

50 |

53 |

48 |

52 |

46 |

47 |

Table 4: Reasons working mums did not request flexible working

Percentage of working mums who did not request flexible working because they were worried about their employers’ negative reaction.

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

43 |

44 |

44 |

41 |

41 |

37 |

44 |

Percentage of working mums who did not request flexible working because they believed it would be turned down.

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

46 |

44 |

46 |

42 |

40 |

40 |

39 |

Percentage of working mums who did not request flexible working because they didn’t need it.

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

5 |

5 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

6 |

4 |

Table 5: Working mums who have faced discrimination or disadvantage as a result of working flexibly

Percentage of working mums who reported experiencing negative treatment as a result of working flexibly.

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

86 |

85 |

87 |

86 |

87 |

85 |

84 |

Table 6: Asking for flexible working in job interviews

Percentage of working mums who would not feel comfortable asking about flexible working in a job interview.

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

48 |

41 |

44 |

42 |

41 |

40 |

39 |

Table 7: Support for policy suggestions

Percentage of working mums who agree that the government should make employers advertise flexible working in job ads – with the successful candidate having the right to take up this flexibility from their first day at work

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

99 |

99 |

99 |

98 |

99 |

99 |

99 |

Percentage of working mums who would be more likely to apply for a job if it included the specific types of flexible working available in the advert.

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

99 |

99 |

99 |

99 |

99 |

98 |

99 |

Percentage of working mums who agree the government should give all workers the right to flexible working from day one in the job.

|

|

North West |

Yorkshire and the Humber |

Midlands |

East of England |

South East |

South West |

London |

|

Percentage |

96 |

97 |

95 |

97 |

96 |

96 |

96 |

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox