BME workers on zero-hours contracts

Insecure work is bad for the workers involved and bad for the economy.

Zero-hours contracts are the most egregious example of one-sided flexibility at work where the employer has absolute power over whether and when to offer shifts.

This joint report by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) and Race on the Agenda (ROTA) shows that disproportionate numbers of Black and minority ethnic (BME) workers are on zero-hours contracts. BME women are particularly likely to be on zero-hours contracts.

It also punctures the myth that zero-hours workers like the arrangement. In fact, most BME workers on variable-hours contracts would prefer to work fixed hours.

We need swift action from the government to ban the use of such contracts. It should give workers the right to contracts reflecting their normal hours of work and implement long-awaited plans to introduce ethnic minority pay gap reporting.

Download full report (pdf)

Introduction

The TUC brings together more than 5.5 million working people who belong to our 48 member unions. We campaign for more and better jobs and a better working life for everyone, and we support trade unions to grow and thrive.

ROTA is a social policy research organisation that focuses on issues impacting on Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. As a BME-led organisation, all ROTA’s work is based on the principle that those with direct experience of inequality should be central to solutions to address it.

This report combines analysis of official statistics, new polling data and accounts of the lived experiences of affected workers to demonstrate the disproportionate impact of zero-hours contracts on BME workers.

A zero-hours contract is one in which an employer is not obliged to provide a minimum number of hours.

New analysis contained in this report reveals that:

- nearly 160,000 BME workers are on zero-hours contracts, around one in six of the 1 million people who are on them, even though BME workers make up just one in nine employees

- one in 20 (4.5 per cent) women workers from a BME background are on such contracts, compared to just 2.5 per cent of white men

- more than half of BME workers on a variable-hours contract would like a fixed-hours contract. Just 27 per cent would prefer their existing arrangement.

Zero-hours contracts are the most egregious form of one-sided flexibility.

Those with no guaranteed hours are often offered work at the whim of their employer, can face irregular shifts and therefore irregular income. Rather than pick and choose their hours, many workers feel compelled to work whenever asked. If shifts are turned down, there’s an implicit threat that they could lose future work.

So flexibility exists for the employer, but not the worker.

This makes it nearly impossible for workers to plan their finances or time. It is a particular issue for parents who must arrange (often expensive) childcare or those with other caring responsibilities.

Such workers are extremely vulnerable when there is an economic shock because it is often easy for employers to reduce their hours or even stop them completely. The risk of a downturn has been transferred from the employer to the worker.

It is also bad for the economy. The OECD has found that countries with policies and institutions that promote job quality, job quantity and greater inclusiveness perform better than countries where the focus of policy is predominantly on enhancing (or preserving) market flexibility.[1]

The prevalence of zero-hours contracts exists in a labour market distorted by structural racism. Our economic structures have exploited and impoverished BME communities nationally and internationally over centuries.

Racial discrimination in the world of work traps BME workers into low waged and insecure occupations. For example, the total annual cost of pay penalties experienced by black, Indian and Pakistani/Bangladeshi men and women is estimated at £3.2 billion per year.[2]

The pandemic has both illustrated and exacerbated the inequalities faced by BME workers.

BME workers have been over-represented in jobs with higher Covid-19 death rates.[3]

And they have borne the brunt of the economic downturn that has accompanied coronavirus. The unemployment rate for BME workers shot up from 6.3 per cent to 8.9 per cent between the first quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021 - an increase of 41 per cent. Over the same period the unemployment rate for white workers rose from 3.6 per cent to 4.1 per cent - an increase of 14 per cent.[4]

This is happening in the face of government inaction.

Ethnic minority pay gap reporting has been on the government’s agenda since it launched a consultation on the topic two years ago. But no action has been taken. And reforms to employment rights promised in the Conservative manifesto and later in the 2019 Queen’s Speech have not been delivered.[5] Indeed, there was no mention of an Employment Bill in the most recent Queen’s Speech.[6]

We urgently need a package to deliver decent jobs for BME workers including:

- a ban on zero-hours contracts

- the introduction of ethnic minority pay gap reporting

- new corporate reporting obligations on firms’ employment models.

BME workers on zero hours contracts

How many?

The use of zero-hours contracts increased sharply in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis as a part of a wider shift towards precarious contracts that has left 3.6 million workers in insecure work.[7]

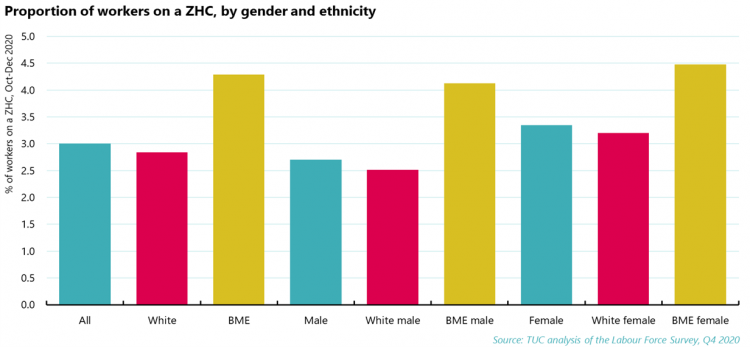

Currently 3 per cent of workers are on a zero-hours contract, according to TUC/ROTA analysis of official statistics.

Within this overall figure, it is clear that BME workers are far more likely than white workers to rely on a zero-hours contract, and BME women more likely than BME men.

For instance, just 2.5 per cent of white men are on zero-hours contracts, compared to 4.1 per cent of BME men.

The highest proportions are found among BME women at 4.5 per cent, compared to 3.2 per cent of white women.

This means that of the 975,000 workers on zero-hours contracts, 159,000 are black or minority ethnic. This includes 78,696 women workers and 79,936 men.

BME workers more likely to experience one-sided flexibility

Sometimes defenders of the status quo claim that workers enjoy the flexibility of variable-hours contracts. The assertion is that workers are able to pick and choose hours to fit around caring and other commitments.[8] It’s a win-win for workers and employers.

TUC research has consistently shown this to be illusory and that for the majority of zero-hours contracts, the flexibility lies with the employer alone.[9]

Polling conducted for the TUC by GQR found that half (50 per cent) of BME workers has been allocated a shift at less than 24 hours’ notice. The survey of 2,523 working people, including 435 from a BME background, also discovered that almost half of BME workers (45 per cent) have had shifts cancelled with less than a day to go. This makes it impossible for affected workers to plan their finances or manage responsibilities such as childcare.

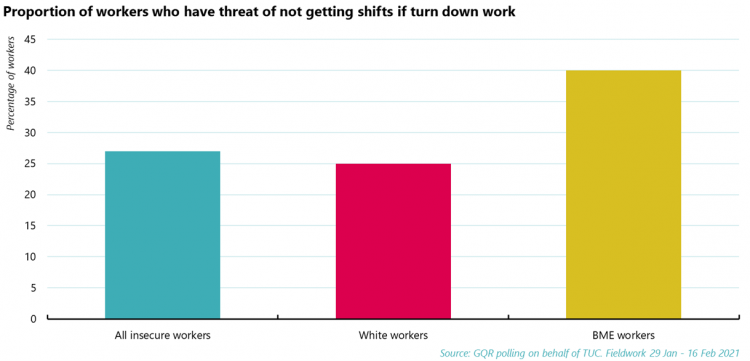

For example, BME workers are much more likely to be unable to turn down work without suffering a penalty. Two in five BME workers report that they faced the threat of losing their shifts if they turned down work, compared to a quarter of white workers.

BME workers want more hours and a stable contract

Our polling shows that BME workers are particularly likely to want more hours and a more stable contract.

And more than half of BME workers report struggling to manage their household finances due to insufficient hours, against two in five white workers.

Sixty per cent of all BME workers desire more hours of work compared to 30 per cent who do not and 10 per cent who are unsure. This contrasts sharply with white workers of whom 49 per cent want to work more hours, against 42 per cent who do not.

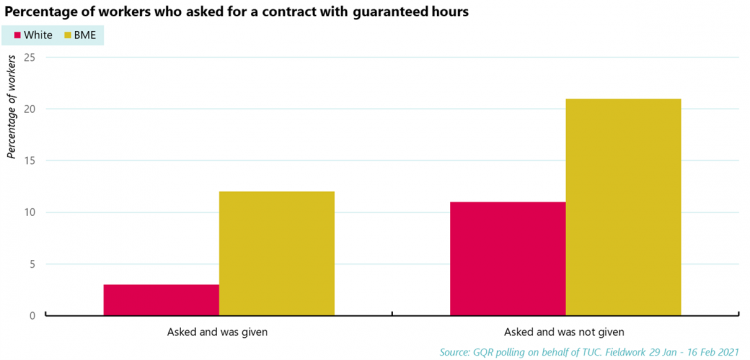

But BME workers typically have little success in securing more hours. Just 15 per cent report having asked and been allocated more hours while one in five (21 per cent) had asked and been denied them.

The vast majority, some 65 per cent of all BME workers, say that their preferred job would be permanent and full-time. Just 1 per cent would opt for a zero-hours contract.

BME workers place particular value on a contract with fixed hours. But they have little success in obtaining them. One in three BME workers polled had asked for a fixed-hours contract but only one in three of those was successful.

A right to a normal-hours contract

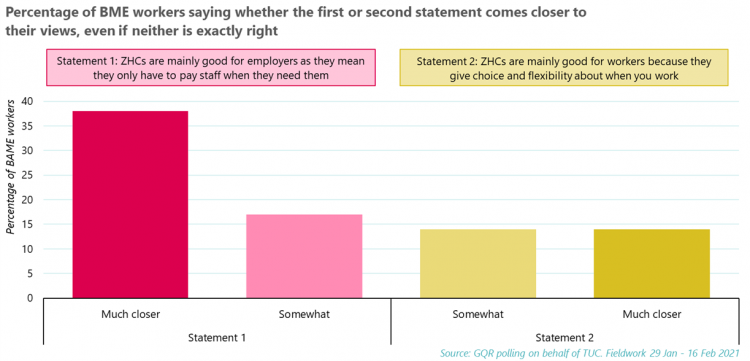

Given their experience, the majority of BME workers agree that zero-hours contracts are mainly good for employers as they mean they only have to pay staff when they need them.

The government has promised giving workers a right to request a more predictable and stable contract.[10] However, more than two years on no legislation has been brought forward to implement this.

But even this right would be inadequate given the balance of power in the workplace.

Many workers would worry about asking in case it affected the future allocation of shifts. Employers would also face no obligation to offer such a contract.

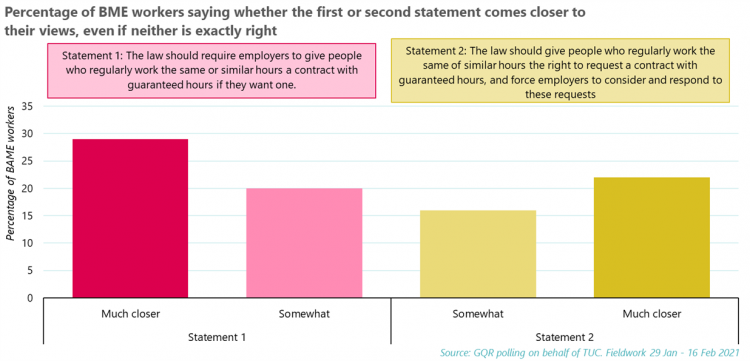

And BME workers agree. Some 65 per cent of BME workers believe that the law should require employers to give people who regularly work the same or similar hours a contract with guaranteed hours if they want one. Just 19 per cent believe that this will lead to employers cutting back on hours.

In particular, BME workers believe, by 49 per cent against 38 per cent, that it would be better for employers to be obliged to offer such a contract than merely give workers a weaker right to request a normal-hours contract.

Workers’ experiences of zero-hours contracts

People from all sorts of backgrounds find themselves working on zero-hours contracts and the range of industries these are used in produces different experiences.

The common threads in these case studies are that the workers had no choice but to work on zero-hours contracts, they felt their jobs were precarious and they had no pay protection for illness or other breaks in work.

While for some, with fewer responsibilities and more flexibility, the contracts were acceptable if not desirable, for others they very much felt like a last desperate option.

Two of the respondents talked about not feeling fully part of the workforce while still feeling bound by the contract and their reliance on the money that they earned.

While none of the respondents were earning much, they all said the precarious nature of the work was an even bigger concern than the poor pay.

AM, 28, delivery driver for a large online retailer, East Midlands

AM is from a south Asian background. He lives in Coalville in the East Midlands, is 28, and works as a delivery driver for a large online retailer. He started working for the retailer 18 months ago and wasn’t given any choice about the type of contract he works on. When he started, he was told that this style of contract would give him flexibility and freedom. The reality is nothing of the kind. AM said drivers “have to work to their rules basically”. He claimed that he was told that he would have the ability to decide his own hours but was never really told about the negative side of the working arrangement.

AM said he would much prefer to be on a standard contract.

AM believes zero-hour contracts are unfair.

He suggested that people are desperate and so will do whatever work is available.

AM’s fellow drivers are from minority backgrounds.

|

PR, 60, cardiac rehab therapist, Leicester

PR lives in Leicester and has had a long career teaching dance and providing dance therapy, particularly for South Asian communities. Trained by the British Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, she is a Phase 4 instructor for cardiac rehab in the community. Although she worked for her local authority from 2002, she doesn’t think she ever had a contract. The work grew from four hours a week to five mornings per week and became her main source of income. There was only ever a verbal conversation and after her hours were messed around with, she asked for a contract. During the pandemic, PR was furloughed by the local authority. This lasted for about three months but she was then asked to be a Covid marshal to help fight the pandemic. Eventually, she was asked by a new officer for a call and assumed it was to discuss new working hours.

PR was extremely upset by this.

PR is pursuing a tribunal case by herself after her union said that, as the Council argues that she is not an employee, her chances of success were poor. In the meantime, she has been working for the same local authority as a zero-hours casual doing Covid recovery shift work.

She has no guaranteed work and her shifts are released on a ten-day basis. The rota is released online a week in advance and while a worker can decline a shift, they then don’t get paid for it. This work could stop any time.

PR says all of her fellow casuals are in the same precarious situation. The cleaners and other workers on casual contracts mainly come from African, Caribbean or south Asian backgrounds according to PR. She’s been having counselling for stress since losing her job. |

MP, 24, various roles, London

MP is a 24-year-old, recent university graduate in London, Black British of African Caribbean origin. He has had two periods of working on zero-hours contracts over the last year. In a nine-month period before the Covid lockdown, MP got bar work from a temping agency at lots of different sites from Alexandra Palace and Guildhall to small clubs.

MP didn’t really mind being on a zero-hours contract for his hospitality jobs.

His second stint was a lot more intensive.

The work was physically and mentally exhausting and so was quite well suited to students and young people.

MP would have preferred to be on a more stable contract so that he knows when and where he will be working.

Like a lot of people, MP took on the zero-hours role because it was the only option available to him.

The shifts at the COVID testing centre ended very abruptly with one week’s notice. The council took over the site and replaced them with its own people. MP was given the option to relocate by his agency but declined. |

Recommendations

A government serious about tackling racial inequality would take steps to tackle inequality and unfairness in the labour market.

It is deeply dismaying that having been elected on a manifesto promise to introduce “measures to protect those in low-paid work and the gig economy”, the government has not delivered.[12]

An employment rights bill featured in the 2019 Queen’s Speech but was never brought forward. And no such Bill was announced in May’s Queen’s Speech.

Meanwhile trade unions are hampered in their work by extremely restrictive rules regarding they organise and take action and no right of access to workers who could benefit from their support.[13]

The government needs to bring forward an employment bill as a matter of urgency.

A range of measures are needed to end exploitation of workers and deal with deep-seated structural racism. We have three key recommendations that would provide a start:

1. Ban zero-hours contracts

Zero hours contracts are among the most extreme forms of insecure working arrangements in the jobs market. Rather than offering genuine two-way flexibility, they hand vast power to employers to take away work at will and leave workers completely at their beck and call.

The TUC and ROTA want these contracts banned. This would require giving workers the right to a contract that reflects their normal hours of work. This should be combined with strong rules requiring employers to give adequate notice of shifts and compensation for cancelled shifts, including costs such as transport and childcare that the worker has borne.

Such an approach would also better protect those employed on short-hours contracts, who might only be guaranteed a few hours of work each week, who have similar experiences to those on zero-hours arrangements.

2. Introduce ethnic minority pay gap reporting

The TUC and ROTA support the introduction of mandatory ethnic minority pay gap reporting by employers to ensure that businesses and other employers identify and address patterns of inequality in the workplace.

We have seen clear evidence from gender pay gap reporting of the impact of mandatory reporting of pay data. Within weeks of the first reporting deadline, all relevant employers had complied with their duty to publish pay data. The high levels of compliance with current reporting requirements evidences the success of a mandatory approach over voluntary initiatives.

Ethnic monitoring systems should cover recruitment, promotion, pay, and grading, access to training, performance management and discipline and dismissal.

3. Corporate reporting obligations

For too long exploitative employers have been able to use arrangements such as zero-hours contracts without having to detail or justify the extent of their use.

Regulations should require companies to report on employment and pay practices across a workforce.

An element of this should require companies to report on the number and proportion of workers on variable-hours contracts, such as zero-hours contracts, within annual reports.

There should also be reporting on the ability of workers to transfer onto contracts that reflect their normal hours of work; the control staff have over working hours; the notice period given for shifts; and whether shifts are paid if they are cancelled at short notice.

Where variable-hours contracts are used companies should be required to justify their use and explain the role such contracts play in their company's employment model.

In compiling the report, the company should engage with trade unions, who can feed in their experience of workforce pay and conditions.

Conclusion

These recommendations alone would not stamp out structural racism in the workplace or rid the economy of insecure work.

But they would crack down on some of the worst labour market abuses and force employers to examine and justify their employment practices.

We now need the government to show that it is willing to make this start.

[1] OECD (2017). Economic Surveys: United Kingdom 2017, www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/eco_surveys-gbr-2017-en/1/2/1/index.html?it…

[2] Henehan, K (27 December 2018). “The £3.2bn pay penalty facing black and ethnic minority workers”, Resolution Foundation www.resolutionfoundation.org/comment/the-3-2bn-pay-penalty-facing-black…

[3] TUC (2020), Dying on the job: racism and risk at work, TUC, www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-06/Dying%20on%20the%20job%20fin…

[4] TUC (18 May 2021). “TUC: BME unemployment is rising 3 times as fast as white unemployment”, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/news/tuc-bme-unemployment-rising-3-times-fast-white-unem…

[5] Prime Minister’s Office (29 December 2019). Queens’s Speech December 2019 background briefing notes, Prime Minister’s Office www.gov.uk/government/publications/queens-speech-december-2019-backgrou…

[6] TUC (11 May 2021). “TUC – government has “rowed back on promise” to boost workers’ rights” www.tuc.org.uk/news/tuc-government-has-rowed-back-promise-boost-workers…

[7] TUC (2020), Insecure work, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-0

[8] Palmer, K (7 June 2018). “Taylor declares zero hours contracts can be positive,” HR Director www.thehrdirector.com/business-news/employment_law/taylor-zero-hours-co…

[9] TUC (2019). Great jobs with guaranteed hours, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/great-jobs-with-guaranteed-hours_0.p…

[10] Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2018). Good Work Plan, HM Government www.gov.uk/government/publications/good-work-plan

[11] TUC (2 September 2019). “One in three flexible working requests turned down, TUC poll reveals”. TUC www.tuc.org.uk/news/one-three-flexible-working-requests-turned-down-tuc…

[12] Conservative Party (2019). Get Brexit done. Unleash Britain’s potential. Conservative and Unionist Party manifesto 2019. Conservative Party www.conservatives.com/our-plan

[13] The TUC proposed a range of measures to expand collective bargaining in TUC (2019). A stronger voice for workers, TUC www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/stronger-voice-workers

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox