MINUS 0.2 PER CENT: The worst time to cut ourselves adrift

But in the UK it’s a particularly worrying backdrop to the potentially catastrophic decision to leave the European Union without a deal.

UK and global weakness

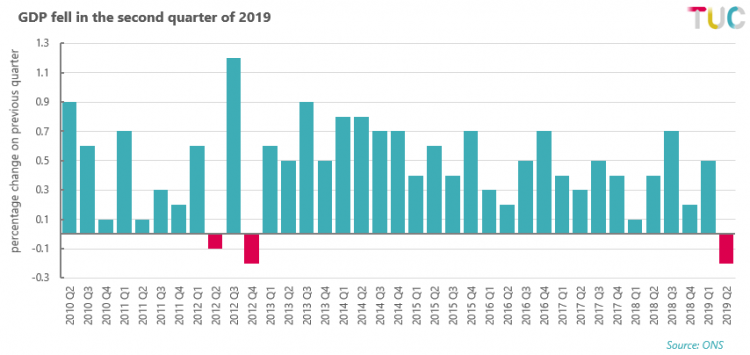

UK GDP for 2019Q2 was -0.2 per cent, down from 0.5 per cent in Q1. Four quarter growth is 1.2 per cent, following 1.8 per cent. Quarter three information will not be released until after 30th October, so this is pretty much the most up to date quarterly information we will have when crucial decisions about Brexit are taken.

Some of the explanation is due to erratic patterns of growth. The decline in Q2 is the flipside of a stronger Q1, thought to be down to stockbuilding ahead of the original Brexit date of March 29th. Q2 also includes a collapse in car production because of changed timing for annual shutdowns, but likely meaning some bounceback in Q3.

But these are very grim figures. Manufacturing was down -2.3 per cent on the quarter, and the ONS see “widespread weakness with 10 of the 13 subsectors decreasing”. The dominant service sector grew by only 0.1 per cent, the worse figure for three years, and construction was down -1.4 per cent on the quarter. Looking at demand, as usual household consumption supported growth, but investment declined by -1.0 per cent (the worse since 2015Q3) and exports were down -3.4 per cent (the worse since 2012Q2).

What happens next is highly uncertain. The Bank of England’s central view has GDP rebounding to 0.3% in Q3, but they missed the severity of the decline in Q2. But everyone is alive to the possibility of resumed recession. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) (to whom kudos for calling the negative Q2) have said there is a 25% chance that we are already in ‘technical recession’ (i.e. two consecutive negative quarters); the Bank of England suggested the chance was 30%. Both of these estimates are conditioned on an orderly Brexit, when no deal has moved from being a remote possibility and become a central assumption of our politics. In the Huffington post Frances O’Grady and Lord Kerslake warned of the “devastating impact” under this scenario: “A plunge into recession … The value of the pound will slump and the price of the weekly shop will jump. And as leaked documents revealed on Friday there will be shortages of medicine and food supplies”. (Uncertainties here mean that forecasters are reluctant to stick their necks out, though NIESR reckon GDP might decline by 2-3 per cent, and the IMF judge outcomes would be 3.5 per cent worse than a smoother exit scenario. OBR worked off the latter to derive a no-deal scenario with a recession of -1.4% in 2010.)

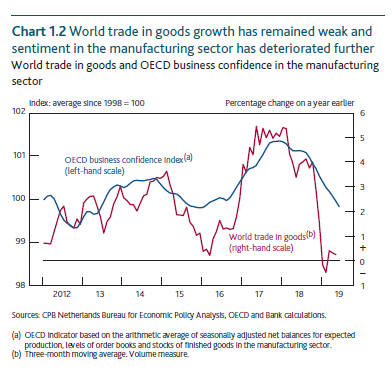

But economic weakness goes beyond the UK. Governor Carney acknowledged these vulnerabilities in a speech titled ‘Sea Change’: “Over the past year, the global economy has shifted from a robust, broad-based expansion to a widespread slowdown”. The international GDP data available so far uniformly show Q2 weaker than Q1. Euro area GDP was down to 0.2 per cent in Q2 from 0.4 per cent in Q1, with

- Italy at zero,

- France at 0.2 per cent from 0.3

- no Q2 data for Germany, but “expected to shrink slightly” according to the Bundesbank.

The US is operating at a higher rate of growth but still slowed to 0.5 per cent in Q2 from 0.7 in Q1 (though trade and investment were both in decline).

Beyond advanced economies, several larger emerging market economies are in serious difficulty – not least Mexico, Turkey, Argentina and South Africa.

Outside GDP figures, many point at the sharp slowdown in global trade (e.g. the Bank chart below) and associated weakness in industrial production. Some drew comfort from the moderating in the pace of decline into 2019, but then this week a steep decline in German production data for June caused markets again to panic.

Central bank policy and financial markets

Alongside flagging growth, central banks have rapidly reversed their policy stance. A year ago we were told of an inflationary threat, now the concern is of too-low (for Carney, “still quiescent”) inflation.

Financial market data partly reflects the stance of central bank policy, see for example the spreads (i.e. differences from interest rates on government debt) on high yield US corporate debt on the below chart.

Stress built abruptly from October 2018, in the wake of continued Federal Reserve tightening and other central banks following suit. The stress reversed when they began to back down right at the end of the year; rate cuts and more quantitative easing are now back on the table.

But even material action from the Federal Reserve, with last week’s rate cut of 0.25 per cent (and likewise cuts in India, New Zealand and Thailand this week), has not been enough to fully allay concerns. As you can see from the end of the chart, spreads are up again this week alongside a torrid time in stock markets.

Brexit and protectionism

Central bank commentary is dominated by threats from rising protectionism, with international organisations also emphasising fragile financial conditions and high private debt.

Unions have condemned the protectionist approach of the US administration that has imposed damaging tariffs on steel and aluminium, putting thousands of jobs in manufacturing at risk.

The TUC has emphasised the importance of the UK continuing to be part of the largest free-trade area in the world – the EU single market – after Brexit. The single market is also the only trade zone governed by a high standard of employment and social rights. The TUC is also calling for the UK to continue being part of a customs union with the EU post-Brexit so that we continue to benefit from the 40 or so trade deals it has with countries around the world.

We don’t believe for one moment in the government’s ‘global Britain’ aspirations that suggest trade deals with the likes of the USA, Turkey or Gulf states could replace a good Brexit deal with the EU. Doubly so, given the deterioration in the global economy. Not only would these trading partners not be able to replace the economic benefits that would come from a single market/customs union deal with the EU, but they are all abusers of fundamental ILO standards and are likely to pressure the UK to lower standards as part of any trade deal.

Fiscal policy

Unsurprisingly given these increasingly grim conditions, the new government have begun to talk up spending plans. And today’s GDP figures show the deteriorating position is set against a modest increase in government spending. NIESR have been up-front in arguing that “policymakers have room to inject monetary and fiscal stimulus to stabilise output”.

This amounts to a partial reversal of the austerity policies that have driven the economy to the brink, and which doubtless played a part in the referendum vote in the first place. Much more is needed. Post-crisis policy has been on a disastrous course. Workers have endured a lost decade and pre-crisis fragility has been restored, and once more policymakers failed to see it coming. But Brexit and the threat of further Thatcher style deregulation is the worst possible solution. Rather than retreat, it would make more sense to cooperate with the world to find some decent answers.

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox