RIDDOR, Covid and under-reporting

This report outlines the TUC’s concerns regarding under-reporting of Covid-19 work-related incidents using RIDDOR, and what can be done to ensure official data better reflects the reality of occupational exposure and fatalities.

What is RIDDOR?

The Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 2013 (referred to as ‘RIDDOR’) is a statutory instrument of Parliament. The mechanism regulates employers’ obligation to report deaths, injuries and illness as well as ‘dangerous occurrences that take place at work or in connection with work.

The regulations require a ‘responsible person’ to report instances - this is generally the employer. Reports must be made within 10 days of the incident.

RIDDOR plays an important role in collecting data on annual and historical levels of work-related injury and fatalities, triggering investigations into occupational safety, ensuring employers follow protocols, and helping safety regulators direct support and enforcement powers.

If an employer knowingly fails to make a report via RIDDOR, they could face a fine.

RIDDOR and the Covid-19 pandemic

Employers are obliged to report cases of Covid-19 infection where exposure occurs as a result of a person's work.

As with any other disease, cases of occupational exposure, or death, must be recorded in official data, and allow for an investigation by the safety regulator where necessary.

Guidance from the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) states:

“For an incident to be reportable as a dangerous occurrence, the incident must have resulted (or could have resulted) in the release or escape of coronavirus...

The assessment does not require any complex analysis, measurement or test, but rather for a reasonable judgement to be made as to whether the circumstances gave rise to a real risk or had the potential to cause significant harm.”[1]

The advice goes on to say the employer “must make a judgement, based on the information available, as to whether or not a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 is likely to have been caused by an occupational exposure”.

In cases where a worker has died with Covid-19, HSE advice says there must be “reasonable evidence that a work-related exposure caused the worker's death” for it to be reportable.

Between April 2020 and April 2021, a total of 32,022 Covid-19 infections and 387 deaths were reported under RIDDOR, according to HSE’s database[2]. The number of deaths being investigated is even lower. The HSE states that, of the 387 figure, some are found to be duplicate reports, diseases misreported as fatalities, or from a workplace outside HSE’s remit and therefore considered by an alternative regulator. As a result, the cases referred to RIDDOR which the regulator accepts as viable is even lower, and as of 19 May 2021, the HSE had investigated or was in the process of investigating 216 Covid fatalities.

Under-reporting

The TUC has concerns about how HSE advice on Covid and RIDDOR is being interpreted. The HSE accepts that there is “widespread under-reporting”: in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, this appears to be an understatement.

It is likely that the official figures – 216 occupational Covid deaths worthy of investigation - is falling well short of the true number of fatalities following work-related Covid transmission.

In a report titled Covid-19: statutory means of scrutinizing workers’ deaths and disease, Professor Agius states that RIDDOR “might have failed in capturing many thousands of work-related Covid-19 disease cases and hundreds of deaths.”[3]

A report from the ethical investments consultancy Pirc concluded Covid-19 infections at food factories could be more than 30 times higher than reported, with the official numbers for cases reported to HSE “lacking credibility”.[4]

Working-age Covid deaths

The TUC is concerned that employers are being discouraged from filing reports under proper mechanisms, and that as a result thousands of deaths linked to occupational exposure of Covid-19 are going unrecorded under RIDDOR.

In the year between 10th April 2020 and 10th April 2021, 126,723 deaths in England and Wales were registered as involving Covid-19.[5] Of these, 14,171 were working-age adults (between the ages of 15 and 64)[6].

In Scotland, there were 9,676 deaths where Covid-19 was recorded on the death certificate within the same period, with 1,092 between the ages of 15 and 64.[7]

This amounts to 11% of all Covid fatalities being among the working-age population in England and Wales, and Scotland.

Despite the total of 15,263 registered working-age adult deaths from Covid-19 in the year April 2020 to April 2021; just 387 Covid fatalities were reported under RIDDOR as work-related in the same period, according to HSE’s database[8].

It is not known how many of the 15,263 registered working-age deaths in Britain were among people in employment. However, there were 5,967 death registrations involving Covid-19 of residents in England and Wales up to 28 December 2020 which included an occupation on the death certificate.

|

Covid-19 deaths |

Total |

|

Overall |

126,723 |

|

Working-age |

15,263 |

|

Reported to RIDDOR |

387 |

|

Investigated by HSE |

216 |

While there are numerous ways people can become exposed to Covid-19; either by travelling to work, socialising or otherwise, it is not unreasonable to expect some of these instances were a result of exposure in the workplace. Certainly, it is likely that more than 2.5% of these deaths (as the RIDDOR data suggests), were the result of occupational exposure, particularly considering the high number of breaches of safety protocols identified in research and polling[9].

Covid fatality by occupation

Available data shows a correlation between certain occupations and Covid-19 exposure and fatality. Data from the ONS indicate that workers in the food service sector, retail and transport are among those with the highest rates of death involving Covid-19[10]. Though the ONS makes clear that findings “do not prove that the rates of death…are caused by differences in occupational exposure”[11], the data certainly indicates higher instances of it.

A later ONS study begins to explain why there is such a difference in infection and fatality rates within certain occupations – because some are less able to work from home, or to socially distance while at work:

“Within every occupation group, there were people who were working from home, some who found social distancing at work easy and those who found it hard. These factors in part explain the differences in testing positive between occupations.”[12]

These findings further explain how it is risk control measures in the workplace – or lack of – that contribute towards the differential in infection rates among workers, i.e. transmission is occurring in the workplace because certain measures are not in place, not despite the fact the workplace is ‘Covid-secure’.

The Environmental Modelling Group (EMG) Transmission Group’s key findings show links between certain jobs and infection and mortality rates. A paper in February 2021 found that “occupations which involve a higher degree of physical proximity to others over longer periods of time” report higher Covid-19 cases.[13]

Despite data showing significant numbers of occupations with a higher-than-average death rate, only around 30% of HSE reports of occupational disease involving Covid-19 are from workplaces not classified as health and social care[14]. For example, while the ONS data shows 608 Covid deaths among transport workers between 9 March and 28 December 2020[15], only 10 notifications were made via RIDDOR in the longer period of 10 April 2020 to 17 April 2021[16] - a rate of just 1.6%.

Among health and social care workers, there is a higher correlation between the number of deaths recorded by ONS and the number of RIDDOR reports made. This could be explained both by the stronger culture of reporting disease exposure in these professions, as well as acknowledgement from HSE that infection following ‘work with peoples known to be infected’ is RIDDOR-reportable.

Unfortunately, due to the timing of data recording and publication by both organisations, it is not possible to compare the numbers of deaths per sector within the same timeframe. However, the table below demonstrates how, over a longer period and encompassing the largest ‘wave’ of Covid-19 deaths, only a small proportion of deaths were recorded under RIDDOR as being a result of occupational exposure.

|

|

|

|

|

Health* and Social Care |

886 |

271 |

|

Transport and storage / drivers and operatives |

608 |

10 |

|

Construction |

305 |

4 |

|

Education |

139 |

9 |

|

Food, drink and tobacco manufacturing |

63 |

3 |

*the numbers of recorded deaths of health workers is likely to be lower as a result of higher numbers in those occupations referred to a coroner

There has been a lack of reporting to local authority enforcement agencies, too. The TUC issued a series of Freedom of Information requests to a sample of 20 councils in England: only one local authority had received a report of an occupational Covid-19 fatality by September 2020.

Potential prescription

The Industrial Injuries Advisory Council made clear in a recent position paper that there is currently insufficient evidence to prescribe Covid-19 as an occupational disease, however, the body stated that “the evidence of a doubling of risk in several occupations indicates a pathway to potential prescription”[17].

It may well be the case that a future prescription of Covid-19 is made in certain occupations. In which case, workers who have for example experienced ‘Long Covid’ may be eligible to claim for Industrial Injury Disablement Benefit, or families may make posthumous claims relating to fatalities. This prospect makes it even more important that RIDDOR data is accurate to support potential future claimants.

RIDDOR in the Health Sector

Under-reporting of Covid infections and deaths has been continuously raised by health unions in tripartite meetings with NHS employers and HSE.

Health unions report advice issued to employers on RIDDOR reporting results in instances where cases being considered valid only where a mask had become broken or had been pulled off by an agitated or distressed patient. This leaves the instances of cases eligible for reporting very limited.

Since April 2020, hundreds of Covid clusters have been identified inside hospitals, care homes and other health and care facilities, with 886 health and care workers recorded as dying with Covid-19 by the end of 2020. Many of these deaths were not recorded under RIDDOR.

This is despite the Environmental Modelling Group (EMG)’s Transmission group identifying that those working in patient-facing roles are “much more likely than the comparison group to be the first case in their household”[18], suggesting the transmission occurred at work as opposed to in the community. This risk gap is however falling, likely because of high levels of vaccination among health and care workers.

A current review by medical examiners in England is investigating whether the deaths of some health care workers should have been RIDDOR reported.

Capacity high, sick pay low

The government’s Environmental Modelling Group (EMG) Transmission Group’s paper in February 2021 stated: “Requiring more people to come to a workplace is likely to increase the risk of transmission associated with that workplace”.[19] In December 2020, the TUC warned that employers advertising seasonal staff to increase the number of people working inside meat factories was dangerous[20]. Food manufacturing had already seen high numbers of Covid clusters: this would exacerbate the problem. While further restrictions easing at the same time undoubtedly led to the subsequent ‘wave’ of Covid infections, the TUC believes increased capacity inside food factories is likely to have aided the spread of Covid among these workers.

The Transmission Group paper goes on to say that a lack of access to sick pay also increased the risk associated with a workplace. his suggests that if an infected person attends work due to financial pressures, there is a likelihood of that infection spreading at work. While access to sick pay remains one of the most effective forms of transmission suppression, it also serves as evidence that workplace transmission occurs when the payment is absent. A failure to record infections associated with these outbreaks under RIDDOR avoids potential investigation and enforcement action.

Covid outbreaks tell a different story

Further TUC Freedom of Information requests to Public Health England (PHE) revealed that between April 2020 and January 2021, there were 4,523 incidents reported in ‘workplaces’. This categorisation excludes infections in care homes, hospitals, education providers, prisons and food outlets; all of which have reported high numbers of infections and outbreaks during this period. Of course, these are also ‘workplaces’ – and the RIDDOR data does include these categories.

These ‘workplace’ incidents are where more than one person tested positive with Covid-19, so in the very least include 9,046 individual infections. In some cases, however, the number of infections associated with one incident totals in the hundreds – yet no RIDDOR report was made. The TUC believes employers are using the cover of ‘community transmission’ and avoiding accountability as a result.

DVLA

A Covid-19 outbreak at the DVLA offices in Swansea in January 2021 led to 560 workers testing positive and one fatality. Initially, the employer declined to submit a RIDDOR report of the fatality, despite prompts by the PCS union. No attempt at an informal investigation was made, with ‘community transmission’ used as an excuse by employers to dismiss any suggestion the death was a result of workplace transmission. Only once it was confirmed that the HSE was investigating did the employer submit a RIDDOR report – two months later.

Bakkavor

Two workers at a salad factory in Kent died with Covid-19 after 70 employees tested positive for the disease[21]. The employer, Bakkavor, refused to report the death via RIDDOR. Before the fatalities, several issues were identified and reported by the union as a breach of safety guidance. Concerns included inadequate face coverings made from ‘snoods’, issued by management; as well as a lack of social distancing. Following GMB union contact to the HSE, a Notification of Contravention was issued to Bakkavor. It is unknown whether either death was eventually reported via RIDDOR.

SERCO Milton Keynes

Two workers employed on a waste contract at Milton Keynes Council died with Covid-19 in early 2021. Neither fatality was initially reported as likely occupational exposure via RIDDOR, despite reports that social distancing was not possible, with staff stretched thin amid a 40% absence rate.

Burnley College

Teacher Donna Coleman passed away with Covid-19 in January 2021. She had been working at Burnley College, where union UCU had previously raised concerns about poor risk control management both with management and with the HSE. The College has refused to declare whether there were known outbreaks of Covid-19 among staff and students, however, it is known that at least 12 employees had tested positive in a single outbreak. The College declared that they viewed the fatality as not RIDDOR reportable and did not complete the form within the statutory period of 10 days. Burnley College declined to carry out an investigation, as HSE advice stated “responsible persons do not need to conduct extensive enquiries in seeking to determine whether a Covid-19 infection is work-related.” Instead, the union conducted its own fatality investigation, declaring the incident reportable, informing the HSE of their position. The family also submitted an incident report to the HSE.

With employers not compelled to file reports, the duty falls on unions and even grieving families to encourage investigations.

Common exposures

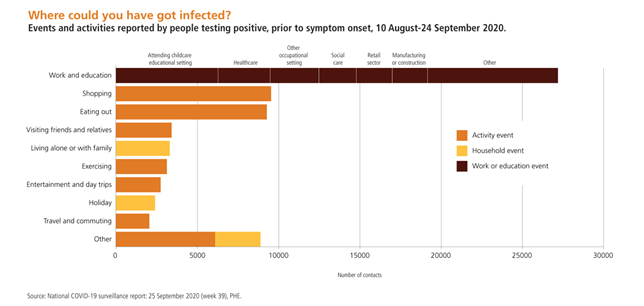

PHE identifies what it terms ‘common exposures’ as ‘vital clues’ in assessing where people were likely to have been infected with the virus. Overwhelmingly, these are identified as the workplace.

“These are the locations or events that a number of different people who tested positive for COVID-19 visited in the same period of time in the days before they tested positive – the activities they have in common.”[22]

Whilst PHE maintains that it may not be possible to definitively say where transmissions occur, the organisation states that “if multiple people all test positive having been to the same gym, at the same time, on the same day, then that would be well worth investigating.” However, a lack of a RIDDOR report makes it much less likely a fatality would be investigated.

PHE’s contact tracing data records details about activities people who tested positive took part in on the days before the onset of symptoms. Consistently, attending either work or an education setting are top of the list.

Graph via Hazards Magazine [23]

It does not appear to be the case that this contact tracing data is used in judging whether an exposure, or fatality, should be RIDDOR-reportable.

HSE advice changed

Until late 2020, HSE advice on RIDDOR reporting of Covid-19 excluded reports from occupations where employees are working with the general public, as opposed to persons known to be infected. Due to self-isolation rules, this means the only occupations where workers would be in contact with persons known to be infected would be health, care and associated professions – excluding a lot of job roles. According to the Institute of Employment Rights, this guidance “could be interpreted as actually downplaying the role of work in facilitating the spread of Covid-19”[24]

This advice has since changed, and the HSE no longer asks employers to discount instances where work with the general public was involved.

What the HSE advice used to say

“Work with the general public, as opposed to work with persons known to be infected, is not considered sufficient evidence to indicate that a COVID-19 diagnosis is likely to be attributable to occupational exposure. Such cases do not require a report.

Responsible persons do not need to conduct extensive enquiries in seeking to determine whether a COVID-19 infection is work-related. The judgement should be made on the basis of the information available. There is no requirement for RIDDOR reports to be submitted on a precautionary basis, where there is no evidence to suggest that occupational exposure was the likely cause of an infection.”

This interpretation of the view of 'occupational exposure' is extremely limited: resulting in employers only being expected to make a RIDDOR report if a worker was known to have been in contact with Covid-19 by working directly with people known to have the disease, rather than having been exposed to it as a result of their work. We now know that many cases of Covid-19 are asymptomatic, or at least take days for onset of symptoms. Most people do not know they have Covid until they take a test, and some fail to be tested because they cannot afford time off work. Many workers may have worked directly with people who had the disease, but for whom it was not yet apparent or confirmed. For example, Covid-19 outbreaks in factories, where it is known many infected workers continued attending work because they could not afford to take time off, would not count as RIDDOR-reportable according to this advice.

At a point unknown, the HSE online advice changed. Current HSE guidance no longer includes the line on ‘work with the general public. In the meantime, it is the TUC’s view that significant numbers of Covid-19 infections, and indeed deaths, have gone unreported, including in transport, retail and other customer-facing jobs. Employers should be encouraged to make retrospective reports to account for this.

The current advice continues to leave judgement to the employer to determine whether or not their workplace posed a risk or not:

"The assessment does not require any complex analysis, measurement or test, but rather for a reasonable judgement to be made as to whether the circumstances gave rise to a real risk or had the potential to cause significant harm.”[25]

For a disease report, there must be a ‘judgement’ made based on information available, but for fatality there is a higher bar, requiring ‘reasonable evidence’. [26]

A further section on the RIDDOR advice page refers to the ‘escape or release’ of Covid, implying accidental leakage of a biological agent e.g. in a laboratory. This does not seem to account for exposure from airborne particles, for example in a poorly ventilated workplace.

The HSE’s guidance on RIDDOR reporting asks that those responsible for making a report first consider “whether or not the nature of the person’s work activities increased the risk of them becoming exposed to coronavirus”. However, it goes on to say that reporting is not required when occupational exposure is suspected based on work with the general public. It is clear though, that certain work activities and work conditions increase risk, and as such reporting should be required.

The reporting requirement in Regulation 9 of RIDDOR does not depend on an assessment that the disease was contracted at work. The TUC believes the HSE Covid-19 RIDDOR guidance minimises the obligation on employers by suggesting it is not necessary to report that a worker has contracted the disease unless it can be evidenced that it was contracted from a specific hazard posed by work. In effect, the HSE has constructed a presumption against the need to report which is not supported by the words of the Regulation.[27]

Lack of accountability

As HSE’s guidance states that it is up to the employer to “make a judgement” on whether a Covid-19 diagnosis was a result of occupational exposure.It is therefore unsurprising that few are reporting, instead choosing to judge that outbreaks are a result of exposure outside of work premises.

The emphasis on Covid-19 as almost exclusively a public health risk, and not a workplace one, removes responsibility from employers and places it with the government and individual workers themselves.

The TUC is concerned that this has led to high levels of under-reporting, with a limited public record of work-related deaths, making it less likely employers will be subject to enforcement action by safety regulators.

From the employer’s perspective, they are simply following official guidance. Supposedly, so long as a workplace is following the advice set out in .gov.uk guidance, it is ‘Covid Secure’ and therefore there can be no workplace transmission. There are two main problems with this notion. First of all, the TUC’s evidence base shows that the government’s guidance is not being followed in many instances[28]. Secondly, it is the TUC’s view that current guidance does not go far enough in recommending and mandating Covid risk control measures. For example, the government (and HSE) were far too late in updating advice on the need for effective ventilation to prevent aerosol spread and has failed to require employers to update or publish their risk assessments despite new scientific knowledge of Covid transmissibility. This emphasis also implies to employers that a report under RIDDOR will be an admittance of guilt that they had breached government safety guidance.

A decade of cuts to HSE and local authority enforcement has also hampered the ability of regulators to carry out investigations, and widely promote the role of RIDDOR. The background to gaps in enforcement is a decade of austerity. Both the HSE and local authorities (the other main workplace safety regulator) have suffered huge funding cuts in the last ten years. In 2009/10 the HSE received £231 million from the Government, and in 2019/20 it received just £123 million: a reduction of 46% in ten years. Less funding means fewer inspections: over the same ten-year period, the number fell by 70%. A study by the European Trades Union Confederation found Britain came only second to Romania in having the highest level of cuts to inspectors since 2010[29].

The last ten years have seen real-term cuts of 50%to the HSE budget[30], with local authorities seeing their inspectorate numbers fall, too. There has also been a dramatic decline in inspections: there were 27% fewer HSE inspections carried out in 2019 than in 2011, amounting to a fall of over 5,700 a year. This must be changed to ensure safety regulators are well-equipped to investigate workplace health risks and take swift action against employers to prevent poor practice.

The government did give the HSE a one-year cash injection to help respond to the pandemic, but this has largely been used to fund contractors, rather than increasing the number of trained and warranted inspectors.

What needs to change

RIDDOR is an invaluable tool. The mechanism provides a layer of accountability on employers and a public record of work-related injuries, exposures and fatalities. With more accurate data on Covid, there would be a greater ability for HSE and others to map and track cases and make improvements to working conditions – as well as take advantage of opportunities to investigate early and prevent future fatalities. However, RIDDOR reports on Covid are scarce, with under-reporting estimated to be on a dramatic scale. This lack of data on occupational exposure and fatalities has made it more difficult to track where outbreaks are occurring and where problem employers or workplace adjustments need identifying. There are several reforms which could help improve this situation.

Clearer advice

The advice and process by which Covid-19 cases are reported to RIDDOR requires urgent attention. Advice must be clearer with regards to how an employer reaches a reasonable “judgement” to determine whether a Covid-19 diagnosis was the result of occupational exposure.

For example, if two or more employees who work in close proximity test positive within a short period, it is reasonable to make a judgement that this infection could have come about from work.

Providing examples of Covid-19 deaths which qualified as reportable under RIDDOR may help. There must also be examples provided as to what constitutes “reasonable evidence”, and for this advice to be consistently applied.

Union reporting

As part of HSE Inspectorate activity, trade union safety reps are consulted to help determine that safety management and risk controls are in order. This can provide inspectors with valuable insight – and sometimes a counterweight opinion - to the employers’ contribution. This same level of engagement and trust should be afforded to the RIDDOR process, with recognised trade unions able to register a RIDDOR report triggering an investigation, as well as employers.

Backdate reports

We now have a greater knowledge about how Covid-19 is spread, and HSE advice has changed to account for this. Employers should be encouraged to make backdated reports.

HSE guidance states that ‘work with persons known to be infected’ could be considered sufficient evidence to make a report. As such, workplaces where there are two or more incidences of Covid-19 and considered an ‘outbreak’ could qualify as RIDDOR reportable. HSE should waive the 10 days statutory notification period and allow employers and unions to backdate reports from previous Covid-19 outbreaks in workplaces.

Equalities

The Covid pandemic has magnified health inequalities in our society. In particular, a disproportionate number of people who are Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) that have died from the disease. However, we are unable to conclude whether this too is the case for occupational exposure.

Health unions have raised with the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) the lack of ethnicity reporting in RIDDOR as a factor undermining our ability to learn lessons on the equalities impact of Covid. While we know anecdotally that BME workers have disproportionately died with Covid, we are unable to draw on RIDDOR data as evidence. The TUC believes adding ethnicity to the RIDDOR reporting process will help inform our understanding of associations between racial inequality and health inequality going forward.

Promotion

The HSE accepts that the ‘RIDDOR notification system suffers from widespread under-reporting’[31]: yet no such government messaging seems to be aiming to rectify this. For the HSE to be able to fulfil its function in advising on future prevention of deaths and illness at work, it must possess a more accurate picture of infections and deaths.

The TUC asks that the government urgently communicate to employers their duty to report all instances of Covid-19 exposure and deaths under RIDDOR.

Invest in regulation

A short-term grant does not fix the chronic underfunding of enforcement. Covid has further exposed the need for effective, quality enforcement: the government must reverse the cuts to HSE and local councils. This means a long-term investment in the HSE and local authority environmental health teams to allow for fully-trained inspectors, infrastructure and resources needed to keep workers safe.

[5]https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19roundup/2020-03-26

[7] https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/general-publications/weekly-and-monthly-data-on-births-and-deaths/deaths-involving-coronavirus-covid-19-in-scotland#:~:text=Of%20deaths%20involving%20COVID%2D19,area%20and%203%20in%20Lanarkshire.

[9] https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/workplace-safety-representatives-sound-alarm-survey-reveals-widespread-covid-secure-failures-0

[10]https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19relateddeathsbyoccupationbeforeandduringlockdownenglandandwales/deathsregisteredbetween9marchand30jun2020

[11] https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19relateddeathsbyoccupationenglandandwales/deathsregisteredbetween9marchand28december2020

[13] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/965094/s1100-covid-19-risk-by-occupation-workplace.pdf

[15]https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/causesofdeath/datasets/coronaviruscovid19relateddeathsbyoccupationenglandandwales

Stay Updated

Want to hear about our latest news and blogs?

Sign up now to get it straight to your inbox